Aziz

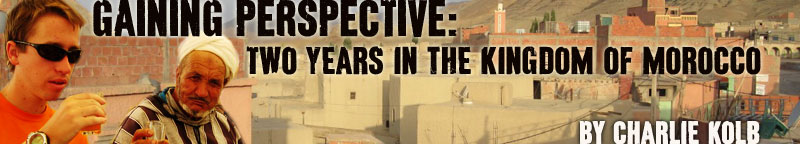

Rain falls softly from a slate grey sky, and drips slowly from the drooping tips of the palm leaves that dominate the view from my hotel window here in Rabat. Birds sing unseen, sheltering from the rain, and people rush across the courtyard beneath my window. The rain today is a slow, gentle fall, almost a mist, and smells of the nearby sea. It’s quiet, for the city, though the call to prayer drifts in on the breeze every few hours. It’s a good day to just sit and write; a good day to read and think. This I do, for a time, but my thoughts seem to turn where they have tended to over the past few months; they turn to a 17 year old boy in my village named Aziz Atmani.

~

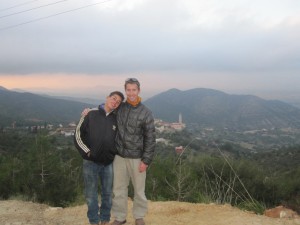

I met Aziz in the early spring of last year while I was on a walk from the nearby lake, accompanying Molly’s dad and stepmom back to the village. I remember the day very well, it was clear and cool, and from the top of the volcanic sill above Lake Tislit, we watched as a pale gold of the spring sunlight painted a startling array of swirling colors across the flatlands between the two lakes. Mark and Molly had gone back another way and I agreed to take the parents back; following the road below a neighboring village, and crossing the fields back to my house.

It was late in the day by then, and the slanting light cast long shadows on Tissekt Tamda, the mountain that looms over my village. The children were walking home from school in clusters of three or four and greeted me loudly and raucously, laughing at my accent when I replied. All save one.

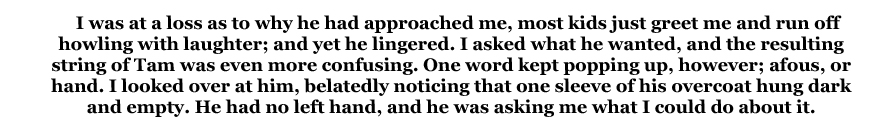

I didn’t see the boy until he was at my side, he said nothing and looked at the ground. He was small and thin, dwarfed by a massive wool coat that was several sizes too big for him; still looking at the ground, he greeted me in a whisper. When I replied, he finally looked up at me. He had the look of the Amazigh that live in the deep mountains; slanting almond eyes, high cheekbones, and brown hair. He said his name was Aziz. I was at a loss as to why he had approached me, most kids just greet me and run off howling with laughter; and yet he lingered. I asked what he wanted, and the resulting string of Tam was even more confusing. One word kept popping up, however; afous, or hand. I looked over at him, belatedly noticing that one sleeve of his overcoat hung dark and empty. He had no left hand, and he was asking me what I could do about it.

I flushed and said I didn’t know anything about prosthetics, that I was an environment volunteer and that wasn’t my area of expertise. He looked unsurprised, and slowly walked away. By this time, Molly’s family had walked off ahead and I was left alone in the fading light, watching Aziz’ back retreat down the road, every movement giving off an air of defeat. “Blati!” (wait), I said as I trotted to catch him. I put a hand on his shoulder and looked at him again before saying “I don’t know anything about what you’re asking, but I will research it; that’s all I can promise.” For the first time, he smiled.

A few weeks later, I had him into my house to take a couple pictures of him and what was left of his hand; as well as getting a clear view of what had happened that had caused him to lose it. He told me slowly and haltingly, and I had to ask him to repeat much of it before I got an idea of the story:

There had been an accident, two years before, when Aziz was just fifteen. Like any fifteen year old boy, he loved playing with fire, regardless of the consequences. I flushed, recalling several close calls I had had with bottle rockets around the same time in my life. Aziz, it transpired, was an avid watcher of NBC action, a channel where they play old, American action movies over and over, without ever once saying that they are fictional (this is important). One day, after watching a movie, Aziz decided to make a pipe-bomb. He took a length of metal tubing and stuffed it with industrial-grade fertilizer (widely available and loosely regulated in a country whose primary natural resource is phosphates). The only problem now, was a fuse… for which he used a match.

You can all guess, as I did, what happened next. The makeshift explosive detonated before he could throw it, leaving his hand a charred ruin. What little remained was amputated at the hospital in Er-Rachidia. I could only imagine the pain and horror of that four hour ambulance ride; the smell of burned flesh, the screaming. Yet he told it to me so matter-of-factly, he had had two years to come to terms with what had happened; what had shattered his life forever. He had gone from whole and normal, to broken and outcast in a matter of seconds. A few snapshots and he stood up, we had gone quiet after his story, but he broke the silence and said “shukran” (thank you). Then he took my hand, kissed it once, and ran out the door into the darkness of the street.

Four months later, after several meetings and innumerable emails and phone calls, Aziz and I waited side by side for a midday transit. It was mid-July by then, and the leaves of the poplars shivered in the warm breeze. The mountains were lit up by the flat, hot light of the summer afternoon, and people hid from the sun in cafés; beneath awnings or sometimes even an umbrella. A month or so before, Hakim, my contact in Rabat, had put me in touch with a prosthetics specialist who lived and practiced in the Spanish enclave-city of Melilla, on the northern coast. He had taken an interest in Aziz’ case, and was on vacation in our area. Our destination was Merzouga, where we would meet the doctor on the fringe of the Saharan Erg, a dune sea. But first we would spend the night in Er-Rachidia, which Aziz had not returned to since the accident.

The transit arrived in short order and we watched as the miles of silent mountainsides and deep canyons slid by our window. A taxi from Er-Rich completed this leg of the journey, and soon we were sitting together at my favorite café, drinking sweet coffee and enjoying the shade provided by the towering eucalyptus trees in the back garden. My friends, Driss and Said, both joined us and Aziz looked back and forth between us as we spoke in English. I explained to him that one of them would be our translator tomorrow, to enable me to speak with the Doctor, who spoke Spanish, French, and Moroccan Arabic—no Tamazight. The entire process hung on what he would tell us the next day, and it would be then when he would tell us whether or not Aziz was even eligible for a new hand.

Said agreed to join us the next day and the rest of the evening was spent introducing Aziz to other volunteers who were in the area. He also had the opportunity to try his first pizza, which he thoroughly enjoyed. We went to bed exhausted, and met Said the next morning at the taxi stand. The morning sunlight was already hot on my back as we crammed into the taxi bound for the city of Erfoud, considered by some to be the gateway to the northern Sahara. I ended up buying out the additional seats in another taxi who said he knew where the Auberge was that the doctor had referred us to. Before long we were powering across the Saharan Hamada, rock-plain, and watching as the heat roiled off the scorched landscape of blackened rock in shimmering, viscous waves. Soon, the sparkling sea of dunes rose from the rippling horizon, their gigantic reality seeming a fevered mirage in the midday heat.

Merzouga itself was not much of a town, the center being a cluster of one-room shops and small hotels, half-swallowed by the eternally encroaching sands. Sun-darkened men in indigo jelaba robes and a few tired looking camels watched as we drove around trying to find our destination The auberges were scattered along the edge of the erg itself, and the shining red-gold dunes loomed over everything as we searched. After a time, we pulled up to a low, earthen building half-buried by the shifting sands. My throat was dry, and sweat rolled down my back as I stepped out into the sunlight and knocked on the front door.

I was greeted by a rather suspicious Moroccan man, who turned out to be the owner, demanding what my business was asking after one of his guests. I looked sideways at Said and asked him to translate for me. “Tell the Spanish doctor that the American is here to see him, and be fast about it.” Shooting me a glare, the proprietor vanished into the dark interior leaving us to stand in the heat, which had climbed to nearly 115°F. After a while, a tall gray-haired man came striding up the hall toward us, with the proprietor trailing behind him sullenly. I had never been more relieved to see anybody in my life.

Aziz was measured and evaluated in the doctor’s sweltering hotel room, and a cast was made of his damaged wrist and forearm. Speaking with the doctor through Said, I was told that Aziz was the ideal candidate for a prosthetic hand. There were a variety of options, but all were expensive; even with the doctor being willing to work for free, this would require a grant of some kind. Though the doctor said he was willing to start work right away, I asked him to hold off while I researched the funding possibilities.

Aziz was ecstatic on the ride back to Er-Rachidia, but I was more subdued; I knew how much work I had ahead of me, and I knew how easily everything could come crashing down around my ears, sliding away like sand through my fingers. That night, I sat on the front steps of the apartment building where we were staying with my friends Marcus and Dipesh, looking up at the stars. I thought of the impossible responsibility and fragility of the task ahead, and how much was riding on it. I remembered what Aziz’ father had said to me a few weeks before as we sat at a café table back in the village “I know that this may not happen. But if you do this for my son, the whole valley will be happy.” The door opened behind me and Aziz sat down on the steps as well. “Hassan, I know this may not work out, but I want you to know that either way, we’ll still have a party in my village to celebrate.” I sat there in silence, not knowing what to say.

~

Peace Corps grants are tricky. They come in a variety of forms, but all are clear that they should be used only for a “sustainable” project, that benefits the community rather than the individual. What I was trying to do for Aziz, was not a Peace Corps project by the standard definition. It would change only one life, rather than many. In my estimation, this was still entirely worthwhile; I came here with the hope that if I could change one life, help even just one person, my time here in North Africa would have been worth it. But how was I going to do it?

I researched on my own for awhile, making phone calls to various Peace Corps staff members trying to work things out. Finally, we found what we were looking for, a much needed loophole; one that could make many small scale projects that don’t fit Peace Corps guidelines a reality. It was so simple, I was at first wary of its legality. Although I wasn’t allowed to raise the money on my own, privately or through grants, there was no reason that an association could not do it on Aziz’ behalf. In essence: If I never touched the money, I wasn’t raising it. I racked my brain, trying to think of a Moroccan association willing to accept donations for a project like this. When I put the question to the Peace Corps staff on the other end of the phone, they replied slowly:

“You misunderstood; when I said ‘any association’ I meant any association.”

“So, means any non-profit back in the states?”

“Yes!”

“How about a church?”

“Sounds fine to me.”

I immediately sent an email to Christ the King Lutheran Church, back home in Durango, Colorado. I told Aziz’ story, and what I had been able to do so far. Their reply was brief, and very positive. The tagline of the email? “Let’s give the boy a hand”

~

Summer crept by, and I watched as my friends back home, faculty from my college (Fort Lewis), and colleagues from my work with the parks donated to Aziz’ cause. Ramadan came and went in a blaze of dehydration and delirium and I soon found my hands full with the Wedding Festival in Imilchil in mid-September. The nights lengthened and grew colder; the days began to be filled with the crisp, golden light of another Atlas Autumn. Finally, I got an email. We had reached, and overshot, our original goal on 9/11, the 10th anniversary of the terrorist attacks in New York which planted the bitter seed of distrust and hatred of Muslims in many Americans. Aziz is muslim, and this fact had been emphasized passionately by my old friend, Kip Stransky, during that service. He explained that on that day, of all days, we should remember to love those who are different from us and to extend our love and goodwill even to those that society tells us we should despise. After all, isn’t that what Jesus would do?

~

The leaves had been swept from the poplars by the river by the bitter winter wind, by the time the doctor informed me he had finished. We set a date for mid-December, and again I found myself sitting with Aziz as we waited for the transit. The morning was pale with frost and the people followed the weak sunlight from café to café as it slowly moved from one side of the street to the other. The first snow of the year glistened on the mountains high above and I was just beginning to warm up when the transit arrived.

In the days that followed, Aziz and I made our way to the Northeast corner of Morocco. We stayed with friends of mine the whole way; they were very generous to take us in, and I thank them for it. Errachidia was the first stop, then ten hours by bus across the Saharan plain to Oujda, a rest in the beautifully forested village of Tafelghalt, and finally to Nador, a city perched on the shores of the Mediterranean. It was a journey of firsts for Aziz, and he marveled at things that I too often take for granted. Here are a few highlights: Stoplights exist to regulate traffic, ice can be used to cool drinks, occasionally the water that comes out of the tap is hot, just because the nice man tried to sell you something doesn’t make it legal, and so on and so forth. It was quite an experience for him, and for me as well, as I got a fresh look at my own life (which I long considered to be mundane and rather normal) through the Aziz’ eyes. We stayed in a hotel, for which the doctor had kindly paid the bill, and walked along the seashore for awhile which was another first for Aziz.

My friend Socorra, who had been in Morocco as long as I, joined us in Tafelghalt and accompanied us to Nador to help out with translation. She was proving an invaluable source of support to both Aziz and me, as Aziz was not always on his best behavior, so two pairs of eyes were better than one. He started calling us ‘Mom and Dad’ which I found rather appropriate as we always seemed to be hollering at him about various things. In the space of two minutes I had informed him, much to his chagrin, that, no, he couldn’t ride the pony that we passed and Socorra then had to pull him out of traffic. So yes, ‘Mom and Dad’.

After our walk, we took him to McDonalds, (yes, there’s one here too) a place I avoided like the plague in the states but rather enjoyed in the Moroccan setting. To Aziz it was a veritable ‘cave of wonders’, with well dressed people forming orderly lines to place their orders, music playing quietly from invisible speakers, and a non-fluctuating room temperature. I can empathize with him of course, as central heating now makes me patently uncomfortable (do people really need their houses so warm!?). Socorra and I chatted in English, blessed English, as Aziz tried to figure out what to do with his cheeseburger and McFlurry. He enjoyed it of course, but not nearly as much as the two rounds of bumper cars I paid for at a traveling carnival on the way back to the hotel.

By the time the doctor arrived the next morning, I had few remaining fingernails after biting most of them to the quick. We exchanged our greetings in the hotel lobby and proceeded up to the room. The new hand was a wonder, a delicate sheath of life-like plastic skin fitting over a carbon-fiber frame. Aziz was dumbstruck by how real it looked. He told me he had never seen anything like this; to be honest, neither had I and I told him so. The hand was adjusted to fit right there in the room and, after an hour or so, it was on Aziz wrist and he was running around giving everyone high fives. The doctor was grinning ear to ear, as was Socorra who had been an amazing translator. I smiled cautiously, not believing it was done. But as I looked at Aziz’ face, I saw ecstasy; so different was he from the tired and downcast boy I had met on the road nearly a year before, that I could scarcely believe them the same person. We had done it, he and I, a little project that could have died at anytime was kept alive by a veritable chain of friends and advisors. This wasn’t my doing, as the doctor insisted to Aziz, I just had the pleasure of being the facilitator—a catalyst for change. But after all, isn’t that what Peace Corps is all about?

~

As the rain slowly dies down and daylight begins to fade from the hotel courtyard, I shut off my computer and sit in the dark quiet, listening to the drops of water falling from the drooping leaves of the palms. I think of all that I have seen in the past 22 months here. I think of the four months I have remaining in Morocco, and wonder what challenges and opportunities they hold for me. But most of all, I think of Aziz and smile.

To read the PDF version of this article, click here and here.

Don’t forget the Zephyr Ads! All links are hot!

Epic story.