The novel is significant, therefore, not because it presents someone else’s fate to us, perhaps didactically, but because this stranger’s fate by virtue of the flame which consumes it yields us the warmth which we never draw from our own fate. What draws the reader to the novel is the hope of warming his shivering life with a death he reads about.

–from “The Story Teller: Reflections on the Works Nikolai Leskov” by Walter Benjamin

Hear me out. I am not very good at making sense of what we are witnessing in the world these days. Notice, for instance, I am making a general claim. The “world,” “witnessing,” “we,” “these days”—these are all contentious terms. If I were reading this essay, I’m not confident I would trust these terms, least of all the writer using them.

There are so many voices now. There are so many spokespersons for a variety of groups and causes. Take a pick—the environment, inner cities, health care, the well-being of pets, the Tall Clubs International Foundation, designed to “promote causes that benefit tall people.” There is a group eager to embrace any of us or perhaps more accurately eager for us to embrace their causes. For decades advertisers have encouraged people to demonstrate their own style, to find their own voice, to be heard. I noticed this particularly in advertisement throughout the 1990’s and early 2000’s. After awhile, I began to question if everyone is speaking in his or her own voice then who is being heard. The most reasonable answer is very, very few of us. The fact is, the vast majority of our voices don’t amount to much.

Even so, I am increasingly troubled by the almost unavoidable punditry that surrounds all of us. Pundits are the few claiming to speak for the many. I mistrust this namely because a single person cannot speak for the entirety of whatever group he or she claims to represent. The whole of any system is much too complex to be delineated by a single representative, which I should think is obvious. Nevertheless, many of us are guilty of positioning ourselves as a representative voice for whatever cause or group we wish to support.

Yet here I am—another voice. Mercifully I do not feel part of any group, which I suspect is what most of us feel. I do not personally know anyone who desires the sum of their identity to be fixed by their political or cultural loyalties. That said, I can envisage people who believe and practice otherwise. I do not feel the positions I hold are incorruptible. I do hold positions, however. I do believe in things. Plainly I write. The act of writing demands the imagination. I believe the imagination is powerful and far reaching. Like writing, the act of reading involves the imagination. And how lucky I am to read! How lucky I am to have had parents, especially a father, who valued books. How lucky I am to live in a place where I can read peacefully each evening and where each evening is peaceful whether I am reading or not. All of my neighbors can do essentially the same. Many decades of arduous work made it possible for me and my neighbors to be able to sit in our living rooms and read a book or stare out of our windows, if we choose to do so. Similarly, it took years of effort for many of us to be able to languish in front of our computer screens, filled as they often are with rage and outrage.

Details from the door of a 12th century stave church in Norway–the point being its inter-connectedness.

I am not being merely rhetorical when I make these assertions. Nor am I being rosy. I am one of the least rosy people I know. But let it be said again, there have been decades of people working to establish the sort of comfort most of us live in, and some of these people have lived and still live closer to us than a few of our fellow citizens care to admit. I think of my grandmothers who lived through the Depression. One of my grandmothers, my mother’s mother, grew up generally poor and picked cotton alongside other family members when she was a child. My father’s mother felt thankful to have shoes while growing up. Not long before she died, she gave me a photograph in which she pointed out how many of the children didn’t have shoes. Many of the children whom she grew up with were too poor to own shoes. She told me if a child had been fortunate enough to have a friend whose family was better-off financially, then that friend may have had an extra pair of shoes to lend or give away. My grandmothers struggled, and I have a better life because of them.

Come September, my family and I will fly to England to say hello to a friend on her birthday. My friend Helen and her family live in a northern part of the country. After celebrating with her and her family, we will head south on a speedy train to spend a couple days in London. I enjoy London. I’ve spent much time there, taking in the finest assembly of museums and galleries in the world, as far as I’m concerned. A lot of blood went into making London. We can imagine our way back to Londinium to have a sense of early blood that went into the city. Or we can remember the Blitz and picture the firewatchers who defended St. Paul’s Cathedral. In September I will ride the Tube across town to eat at a superb restaurant and later that evening, I will lodge in a comfortable room. All the while I will be seeing remarkable inventions, architecture and art in a city that was on fire 77 years ago.

But here’s a rub. A few people have said to me: “Yes, we know all of that. We are protesting for those who do not have privilege. We are angry for the way things are. We are angry for those who go unmentioned.” Most of the time, I do not know how to respond. I am willing to hear their arguments, but frankly, I mistrust how upset some people claim to be—people who live profoundly comfortable and safe lives, who have comparatively easy jobs, who speak to us from and within various media, from news programs to Youtube channels, who write for slick magazines and websites and academic journals. Maybe some of these people are genuinely upset by what they call injustice, intolerance, bigotry and hate. Maybe they are genuinely angry at whom they call backwards, hypocrites, dangerous mother fuckers and the labels go on. Some of my friends are troubled by the times, but I trust them, which is to say I trust their integrity, whether we agree or disagree on given issue. Mentioning my friends is not a casual qualifier either. The fact that I know each of them, with their individual beliefs and considered opinions, is an essential recognition in terms of my regard and for my willingness to listen to their arguments.

“Shoes on the Danube.” These iron shoes mark where Jewish families were slaughtered on the bank of the Danube in Budapest. The shoes, of which here you are seeing only a fraction, mark where people were told to take off their shoes before being shot and thrown into the river.

There are media and entertainment personalities who champion admirable causes. I can speculate that any number of these people give millions of dollars to causes and institutions. Jimmy Kimmel, to use a recent example, made generous contributions to the L.A. Children’s Hospital after the staff cared for his infant son. Furthermore, after Kimmel publically thanked the doctors and nurses, there was a significant increase in donations to the hospital. His forthrightness and contributions to the hospital are admirable. But admittedly, I bear my own prejudices. As a result, I find it ridiculous to be lectured about climate change, for one, or poverty, for another, by individuals who fly about the world in private jets, or an actor who allegedly spends $30,000 a month on wine (allegedly, as though such purchases were illegal), or another actor who dropped $250,000 on a stolen dinosaur skull.

Nonetheless, most visible media and entertainment personalities have worked extremely hard for their careers. Read Steve Martin’s Born Standing Up to appreciate years of what he calls “perseverance.” But the old “don’t piss down my back and tell me it’s raining” alarm rings rather loudly when the likes of Madonna demand attention for her compassion, for her supposed empathy. I am generalizing, but from what I can observe, the majority of public conversations running along the lines of have and have not’s, who’s guilty and who’s not, who’s oppressed and who’s not, become, well, oppressively dogmatic. The lines, so to speak, have been deeply drawn, even trenched. We might do well to remember that all public and occasionally private discourse is an effort to define and ultimately control the terms of a conversation. Understanding this, we should ask ourselves what do manipulators on various sides of these conversations desire. It is not clear to me how anyone entering political or cultural discourse comes out unfairly scathed or judged. Our national and corporate efforts at dichotomizing our conversations aren’t working very well either, unless of course these divisions, for whatever reasons, are desired.

As I suggest in my title, it could be worse. Our circumstances, our communities, our daily lives, our troubling divisions along cultural and political lines, they could all be worse. And worse has a much easier entry point when we stop talking about people as people and begin to talk about them as though they are simply, all too simply ideologues with whom we disagree or perhaps despise. Too often history has been clear about the consequences for losing sight of another’s humanity, or to refer back to Benjamin, though his ironies are more severe, the other person, like us, may be shivering.

At least I have a book to sit with most evenings. Books and evenings bring me considerable pleasure. For what it’s worth, my own reductive leanings insist that I remain mindful of what was difficult to achieve, to build, to stabilize, to maintain through the efforts of mostly average people, including my earlier mentioned grandmothers and then my grandfathers, one who could hardly write his name but became a successful heavy equipment operator, and the other who battled across Europe during War World II and latter raised pigs out back of his house. They were good men, my grandfathers. They were flawed, too, but I am glad I knew them. Someday, maybe I can tell their stories.

Damon Falke is the author of five books, including most recently Now at the Uncertain Hour. His poem Laura, or Scenes from a Common World was produced by Square Top Theatre and was an Official Selection for AVIFF Festival at CANNES.

Visit his website at https://damonfalke.com/

Click Here to Follow his Facebook Page.

To comment, scroll to the bottom of the page.

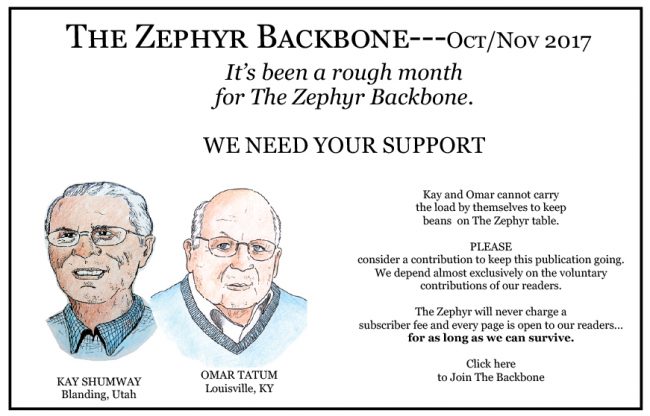

Don’t forget the Zephyr ads! All links are hot!