“I always liked to hear about the oldtimers. Never missed a chance to do so. You can’t help but compare yourself against the oldtimers. Can’t help but wonder how they would have operated these times…. I don’t know what to make of that. I sure don’t. The crime you see now, it’s hard to even take its measure. It’s not that I’m afraid of it… But, I don’t want to push my chips forward and go out and meet something I don’t understand. A man would have to put his soul at hazard. He’d have to say, ‘O.K., I’ll be part of this world.’ “ – Ed Tom Bell

“What you got ain’t nothin’ new. This country’s hard on people. You can’t stop what’s coming. It ain’t all waiting on you. That’s vanity.” – Ellis

From the film, No Country for Old Men

____________________

Fishing

There is a spot that I like to take my buddies fly fishing along the Weber River. It’s got good holes. Swift but not too swift runs. And, hatches that are damn near legendary if you happen to find yourself in the middle of one. I never used to fish the Weber much, because it can test a person’s patience and in general, their willingness to even give the sport a chance. I once broke a rod straight in half after a frustrating day out. Not one of my finer moments, but I sure as hell felt better afterwards until I realized I didn’t have enough money to replace it! When I was younger, I’d never leave the confines of the Provo River, about 30-45 minutes north from the Weber, as access was ample and little of the Heber Valley had been discovered by anyone who’d think of changing it. The valley possessed gorgeous, spanning valley views from north to south. Midway, a small town settled by Swiss immigrants, buffering it’s western flank as Mt. Timpanogos protects the valley from the south west. Daniel’s Summit and Strawberry off to it’s southeast. The western edge of the Uinta’s off to its northeast. Generally, the river existed as a sort of known but not-known secret among fly fisherman. An idyllic scenery for some of the best trout fishing in the country.

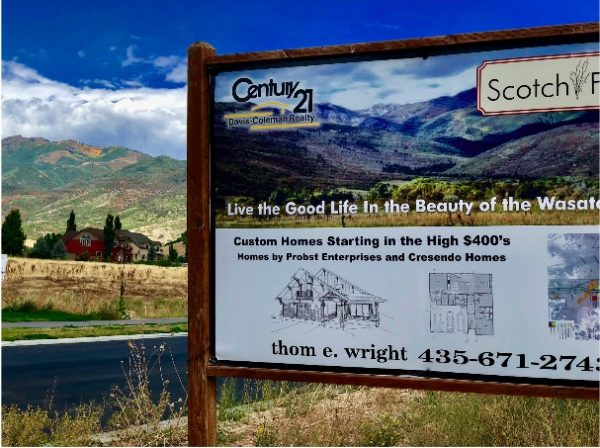

The Heber Valley – while still hosting some of the best trout fly fishing in the West – has dramatically changed. Through the thanks of water conservationists rebuilding the river it has made the stretch even better, in terms of its original, and intended, ecology. However, it coincides with the development and rebuilding of the Heber Valley, and towns around it, that has altered it from it’s once tranquil bends and farm lands, to multi-million dollar acreage that now looms large over the valley. Hence, I now stay east on I-80 rather than turning towards Heber and fish the Weber much of the time. It’s open farm lands and meandering banks just as idyllic as the Provo once was. I find it easier to escape crowds, too. Humans, in general, really. I search for space.

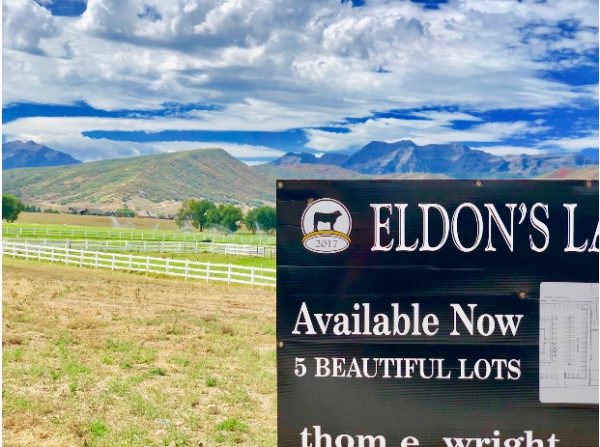

Although, even on the Weber nowadays, that’s tough. There is a term in fishing called “pressure”. Meaning, that if a stretch of river gets too many people, it puts so much pressure on the river and ecosystem that the fish will eventually leave. It wasn’t until a recent trip with my buddy that I started to notice that pressure on the Weber is up dramatically. I turned to him and pondered, “When will this end up just like the Heber Valley? When will this open farm land be bought up and converted into something perverse? When we will turn a bend and see a subdivision rather than wild grass?” We had a long conversation about it. And, we both came to the conclusion that the stretch of river we’d just fished would ultimately end up like the very spots we’d fished on the Provo, confined in the Heber Valley: crowded by townhomes, multi-million dollar vacation dreams (maybe even by the Kardashians!), humans, and lacking the very thing we liked about fishing it – space and tranquility.

What Is It About “Space”?

The West, has, and may – hopefully – always be about space. While the early settlers certainly came West for a variety of economic and cultural factors, the allure of a better life has always existed within that context. I am of the belief that a big part of that is that the allure of the West was, and is, that humans can get back to something primal. The primal spirit of not living on top of one another. The primal spirit of reconnecting with the very planet that gave you birth. The primal spirit of what it means to be human. And the historical evidence of those who paid the price to do so in the early years of western “white” settlement, are full of this. As Wallace Stegner explained, the West is a geography of hope. And I suspect it will continue to be so. For now.

I say this, because the West is rapidly changing, and much of the space that we seek is turning into something entirely different. My hometown of Park City, Utah, the Heber Valley I mentioned above, Jackson, WY, and Moab are prime examples of how the West is transforming from quiet solitude to playground for the rich and famous. Towns that used to exist in peace because of their relative remoteness and perceived lack of culture have withstood decades of unfettered growth while maintaining undebatable charm. But that began to change when mass migrations of people began changing the landscapes. The model goes something like this: person visits small, quaint town and falls in love with its remoteness, its laid back way of life, its “I feel like I can disconnect here for a while”… its space. Soon, if they have proper financial backing, they can buy some land and build a new house on it. Soon after, said person starts thinking “what if we changed this? What if we changed that? What about a drive-thru Starbucks instead of the old cafe? Can you imagine what a lucrative business that would be?!” The very charm and aesthetic they loved about the place is the first thing that starts to get “modernized”. It’s as though they forget the very factors that caused them to fall in love with the place to begin with!

Commentary on the human condition? Unwillingness to let go of creature comforts? I do not know nor understand. There are a number of economic factors that “flawlessly” speed up this process of growth and development, however. Growth and development… Interesting words to use when we think about our environment. We think of both in positive manners. A child grows into an adult. We measure our income, and consider it growth. We consider development of new skills as a way to measure professional growth. It’s no wonder we’ve all been duped into automatically associating these terms as positive when we hear a plot of open land is being “developed” for “growth”. Rather, I’d use the words overrun and swelling. Like a river that is about to overrun or swell over its bank.

But to simplify this force of change into such basic terms would not paint the whole phenomenon. It’s somewhat of a western-varied version of what’s called the doughnut effect (irony not lost on the photo chosen for the referenced websites page banner). Simply, as people obtain wealth, they tend to leave city centers for more open space, thus leaving an empty center (the hole in the doughnut) where they once lived. In urban areas, this means leaving the city for the suburbs, and the areas considered “suburban”, just grow more and more rings around the original doughnut in an outward fashion. In small towns across the intermountain west, this is somewhat similar, but usually from more far reaching places than the nearest big town.

Most of these small towns have, for generations, sustained themselves economically through ranching, farming, working mills, mining, etc. They literally live(d) off the land, and these industries provide(d) a sustainable and living wage. And by sustainable and living wage, I mean wages that allowed families to put down roots, buy a home, raise a family, go to schools, etc. But, as these jobs either became harder to make a living from, or resources and minerals diminished, ran out, or devalued, it became harder and harder to make a living. Further, as aging populations got older, their children (who’d likely inherit the family land) saw no purpose to stick around town due to current opportunities and a declining rate in livable wage jobs. Couple that with a new wave of financially-equipped out of town investors who are more than eager to buy some land in “paradise”, and it’s no wonder why the families or children who are left end up selling it off to the highest bidder – ain’t got any other easy ways to make a few hundred thousand! And the highest bidder often wants to develop the land for the town’s new subdivision or keep it to themselves and a 3,000 square foot vacation home. And slowly, or rapidly, the space gets parceled off, piece by giant piece. The fields no longer waving with a gentle breeze, but a giant bulldozer.

Growth: It’s a Good Thing… Right?

Utah is, depending on the year, the fastest growing state in the country. St. George, a town that due to water or lack there of, should not even exist, is the fastest growing metro area in the United States! It is said that by 2050 or so, the Salt Lake Valley will contain a population the size of Philadelphia. Since 1990, Park City has more than doubled its population. Unsurprisingly, open space has declined:

“Twenty years ago, Snyderville Basin, which extends from the McPolin Barn on Highway 224 to Kimball Junction, was mostly farm fields and sagebrush. But from 2000 to 2010, its population rose from 3,636 to close to 22,000, according to census estimates.”

And, if you talk to anyone who lived in Park City in the 80’s and 90’s, few would claim that they like the place as much as they once did. “Park City has no locals anymore”, one friend I grew up with stated. “What used to be a small mountain community is now full of retiring transplants or 2-week vacationers from California, New York, and Texas… anywhere but from around here”, another childhood friend explained. Gone are the Mt. Aire Cafe’s. In are the luxury fur retailers.

The Heber Valley, specifically, Heber City, is even more astounding. Between 1990 and 2017, the town population jumped by more than 230%. For comparison, during that same span, Fort Worth, which in 2014 was the country’s fastest growing city, has only grown by 95%. Yet, when it comes to towns like Moab and Escalante, Utah, the stats don’t necessarily reflect what’s actually going on. For example, Moab looks fairly stable and Escalante, most years, officially, shows a decrease. But, if you ask anyone in Moab about what is happening to the population, you know that these numbers are misleading. As with the case of Escalante, what is happening is something becoming all too familiar in western small towns: the number of people buying land and property for part-time use or vacation use is drastically rising, while those who live in the town full-time are steady or declining. And so is the open space.

At the moment, to my knowledge, there is no way to pull official stats on the breakdown of new, part-time residents moving in, versus full-time residents moving out in the city of Escalante, Utah. The only official stats provided by the government are County based. Yet, it’s fairly obvious to anyone who lives in the town. One such sign of the town’s shifting dynamics is that Escalante high school is rapidly shrinking – a sign that people who I have spoken with in town consider a major warning sign that the town’s growth is not based on couples settling down to have and raise children there. Things appear so dire that I was even told recently the town is in regular discussions about closing the high school all together.

In some ways this makes sense: while local retail shops continue to do well (some of whose owners I consider good friends, for the sake of transparency,) most of their seasonal employees cannot afford to live in the town during the offseason of Nov. to mid-to-late Feb. In those months, there are no jobs, as everything tourist-based is closed. And because there are few jobs outside of tourism-based ones, it makes it nearly impossible to afford to stay year round. Thus, you end up with a majority of this workforce who are young travelers willing to come for the season and then head back elsewhere, who may or may not ever come back. This is not an ideal situation if your town is trying to attract young people who will set up roots and make the place “home” but it works fine if the majority of the people buying property and land are simply coming part-time. It would seem then, that what is happening in Escalante is a town becoming occupied by part-time residents while the traditional jobs and lifestyles slowly go elsewhere as living-wage jobs are reduced – or at the very least, homes and property becomes too expensive for anyone locally to buy.

Pressure

I can already hear the cries from disapproving readers–and for references to the iconic Simpsons episode in which “Old Man Yells at Clouds” to come roaring in – even though, to my knowledge, I am not that old. But, I do believe with all of my heart that these are important aspects of “progress” and “growth” that need to be addressed, as our small towns across the Intermountain West lose more and more of their space to land development. It is causing real issues. For one, affordable housing is a big issue in almost all of the cities I’ve mentioned in this piece. As more and more wealthy investors buy up chunks of these small towns, it puts pressure on the few remaining affordable living options for the service-based employees who need roofs over their heads. In Escalante, it is generally believed that at any given time, ⅓ of the towns homes and dwellings are unoccupied. Yet, the town faces a housing shortage – because many in town, the service-based employees, do not make a livable wage to meet rent prices for the few places available for long-term or seasonal rent.

I can already hear the cries from disapproving readers–and for references to the iconic Simpsons episode in which “Old Man Yells at Clouds” to come roaring in – even though, to my knowledge, I am not that old. But, I do believe with all of my heart that these are important aspects of “progress” and “growth” that need to be addressed, as our small towns across the Intermountain West lose more and more of their space to land development. It is causing real issues. For one, affordable housing is a big issue in almost all of the cities I’ve mentioned in this piece. As more and more wealthy investors buy up chunks of these small towns, it puts pressure on the few remaining affordable living options for the service-based employees who need roofs over their heads. In Escalante, it is generally believed that at any given time, ⅓ of the towns homes and dwellings are unoccupied. Yet, the town faces a housing shortage – because many in town, the service-based employees, do not make a livable wage to meet rent prices for the few places available for long-term or seasonal rent.

A day or so before I put the finishing touches on this article, I returned to the Weber to escape the atypical heat and crowds of Salt Lake City. I waited and waited for any signs of fish, but while I waited, I encountered several humans and few fish. And, although I am not the brightest guy in the world, I couldn’t help to think about the theory of “pressure” on the river as it relates to space. What happens when every stretch of the river has too much pressure? Where will the humans go? Jesus, where will the fish go!? What happens when there is no more open space? What happens when the last vestiges are bought up and developed? When there is no more open water for us to seek shelter from the pressure? When there is no more space for us to find ourselves… to connect to something bigger. Perhaps that is too much for the old man who yells at clouds to consider. After all, there is no country for old men.

To comment, scroll to the bottom of the page.

Don’t forget the Zephyr ads! All links are hot!