<<Prev Home PDF Next>>

it

to my favorite author. Of course, Abbey didn't live there as he'd

claimed—he'd never even been there. Still my passion for Glen Canyon

stayed red hot.

But

one day, more than a decade ago, I was ranting about dam removal to an

environmentalist pal of mine (an attorney of course) and I noticed a

certain lack of enthusiasm on his part.

I said, "What's wrong with you? Don't you want to see Glen Canyon restored?"

He smiled sadly and replied, "It won't be the same."

ly

was, as Eliot Porter later said, "The Place No One Knew." It was full

of history, going all the way back to the Anasazi. The Glen was

inhabited by just a handful of hermits and oddballs and explored by a

strange mix of cowboys and prospectors and river runners. The legendary

Bert Loper lived down there, in his old cabin that he called The

Hermitage. Art Chaffin ran the ferry at Hite. The place was full of

ghosts.

The

men and women who had stumbled upon Glen Canyon in the 1940s and '50s,

who really found religion of sorts here, were like an exclusive

congregation. Their names, like Glen Canyon itself, are the stuff of

legend. Glen Canyon will always be inextricably linked to the lucky

few like Ken Sleight and Katie Lee and Harry Aleson and Moci Mac and

Doc Mar-ston. How much did this place mean to them? Watch Ken and Katie

choke back tears a half century after the Glen's demise. The loss runs

deep.

"All that's gone," my friend said. "You can drain the reservoir but you can't bring back the way it felt. That's gone. All of it."

He looked at me and said, "If they ever drain the lake, it'll be a ZOO down there."

WATCHING LAKE POWELL GO UP & DOWN.

I

drove past Glen Canyon Dam last week, on my way to visit friends in

Springdale. It hasn't changed much since my last visit, or my first for

that matter; it's still the biggest chunk of concrete I've ever laid

eyes upon and it still floods one of the most beautiful sections of the

Colorado River—Glen Canyon.

Of

course, I've never really seen Glen Canyon in its pristine state. When

the dam's diversion gates closed in 1963, I was still a kid in

Kentucky, oblivious to these kinds of devastating man-made disasters.

Oh to be that innocent again!

My

introduction to Lake Powell and its consequences came to me via an

aunt I barely knew. Bertha Gunterman was a frail but feisty retired

editor for Random House, living in New York, when she got wind of my

interest in the West. She began sending me clippings from magazines

about The Dam and the effect it was having both downstream in the Grand

Canyon and, of course, the utter destruction by drowning upstream.

Early

on, it had become apparent that this dam was a bad idea. For example,

water released from the bottom of Glen Canyon Dam is cold—very cold—and

consequently, it killed most of the native aquatic life in the Grand

Canyon. They've since stocked the river with trout, which is wonderful

if you want to imagine you're fishing an alpine stream.

The

dam had been built to "save" water for the Lower Basin states of the

Colorado River Compact, but evaporation and bank storage was diverting

millions of gallons of water away from the reservoir. That's what

happens when you build a reservoir in...the DESERT! The politicians

could just as easily have moved the measuring point to Hoover Dam, 300

miles downstream, but that would have made too much sense and saved too

much money. So the Bureau of Reclamation built another dam.

Still,

when the drought in the early 2000s pulled Lake Powell's elevation down

by 150 feet, I was anxious to see what the re-exposed parts of Glen

Canyon would look like. Abbey had always insisted that Glen Canyon was

not gone, that it was simply in "liquid storage," waiting to be

restored and rejuvenated.

In

March 2005, the reservoir fell to a level that, if my friend Rich

Ingebretsen's calculations were correct, meant that one of the

canyon's most iconic natural features, Cathedral-in-the-Desert, was

completely out of the water. Ingebretsen is the president and founder

of the Glen Canyon Institute and is probably more dedicated than anyone

to its restoration.

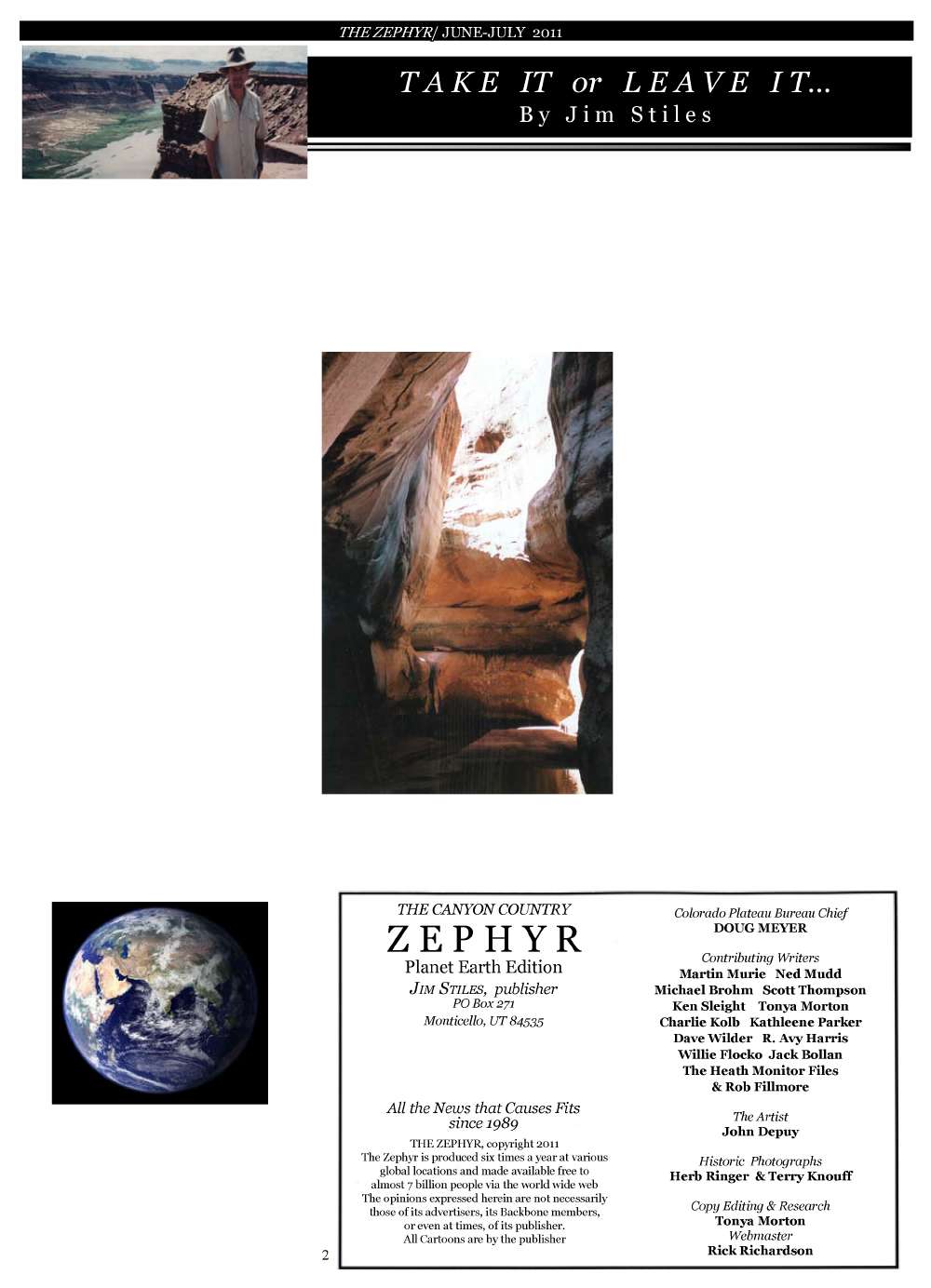

We'd

seen the photos of this extraordinary side canyon, with its tapestried

walls and hanging gardens and its fluted waterfall. What would it look

like 42 years after it went under? Would it have retained its splendor

after all these years? And would it feel the same? Ingebretsen and I wanted to find out.

To

add some irony (or hypocrisy?) to our quest, we rented a speedboat to

travel the 30 miles down lake from Bullfrog Marina—the very motorized

contraption that we both claim to loathe. But we forgot about our

contradictions when we found the Cathedral looking almost exactly as it

had been portrayed in the old photos. Even small rocks on the ledges

above the

In

my twenties, I became obsessed with The Dam and Glen Canyon. After my

move to Utah, I made frequent trips to the reservoir and to Glen

Canyon's above-water remnants. I discovered Ed Abbey and read The Monkey Wrench Gang about

200 times. I dreamed of "the precision earthquake" that Abbey's Seldom

Seen prayed for. I drew a cartoon of The Dam with a gaping hole in its

concrete facade and drove all the way to the remote Wolf Hole, Arizona

to present

It

was true that the Glen Canyon Story went beyond the physical

resource—there was a romance to it that elicited visions of a Desert

Xanadu. Tucked away in this remote, unknown corner of the Southwest was

an entire canyon system, almost 200 miles in length. It was one of the

best kept secrets in America. It tru-

www. cany oncountryzephyr. com cczephyr@gmail.com

Why are our days numbered and not, say, lettered?

— Woody Allen

<<Prev Home PDF Next>>