<<Prev Home PDF Next>>

Gaining Perspective...Volume 4

Two Years in the Kingdom of Morocco

By Charlie Kolb

pleasant, but surreal, dream.

When

I reached the house, I yelled a greeting from the door before walking

inside. I shook hands with my host mother Rkia, father Said, and my

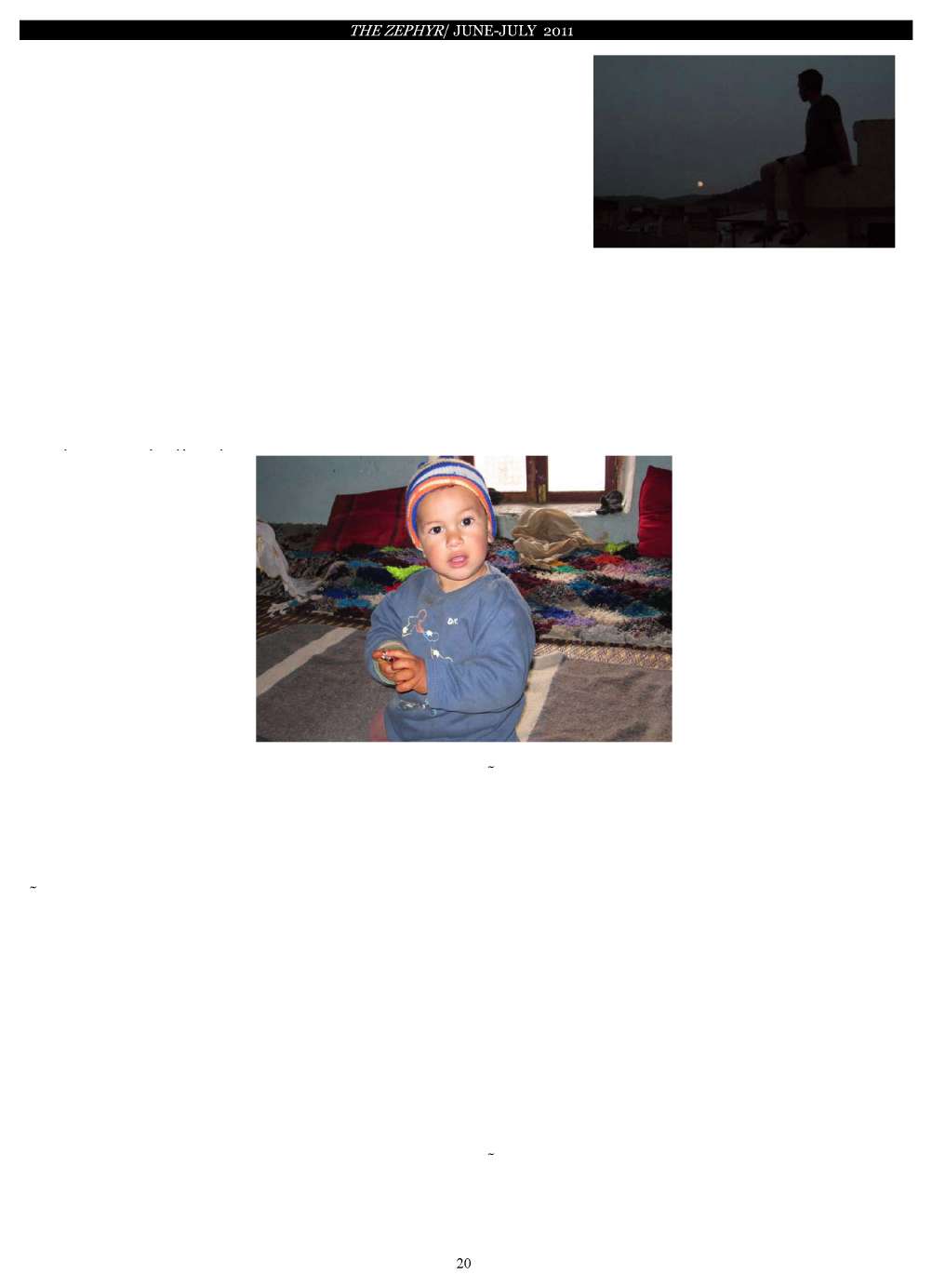

siblings Mo-hamed, Rachid, and Fatima. When I reached the baby,

Sufiyan, almost 2 years old, he looked up at me shyly with his big

brown eyes. "Sim" (shake hands) I said, and he held out his left to me.

I smiled and said "yadnin" (other one), and he offered his right. I

took it in mine and shook it once solemnly. He grinned at me, flashing

his baby teeth, before burying his head in his mother's arms. Now a

toddler, Suf was barely able to crawl when I arrived here last year.

Now he not only walks, but runs; he has learned to say some simple

words and can now ask for what he wants. Watching him grow and change

is another reminder of the passage of my time here and of all the

wonderful things I have seen.

Spring

has come to the Atlas. The apple trees are blooming and the poplars on

the riverbank are furred with a delicate haze of pale green leaves. The

willows are heavy with fuzzy grey catkins and the songbirds have

returned to perch on my windowsill when I open them wide to let in the

shafting morning sunlight. Tourists go in and out of the village on

motorbikes or riding in expensive Land Rovers. "Adventure Tours" they

are called, though I have a hard time seeing how a one or two day stop

in my village is considered an adventure. 14 months here and even I

feel that I have barely seen a fraction of what the Atlas and its

people have to share with the world.

A

few weeks ago I stood out on the fringes of a wheat field with a friend

of mine who I will call "MoHa". He is the brother of a local store

owner whom I know well, and one of the few people willing to let me

work in his fields with him. I try

I

sat down next to Said, in my proper place as another adult male, and

spoke with Rkia from across the room. She left after a few minutes and

returned with a conical clay tajine filled with spiced meat and

vegetables which I ate with relish. I stopped eating meat a few months

ago and Rkia no longer offered it to me, instead moving it to an area

of the dish where others would eat it. We ate with our hands, using

crusty fresh bread baked that morning as utensils. A teapot and basin

was offered to each of us to wash up after the meal was finished and

the children went out to play. Rkia, Said, and I stayed in the small

room and enjoyed a cup of sweet Moroccan tea to aid in digestion. I

left soon after that and stopped again in the graveyard watching the

light play over the stones and shimmer on the swaying grass.

to

come here once a week and learn about the farming methods practiced in

this area for millennia. After diverting water from the river through a

maze of shallow ditches, we removed the plugs of earth and sod and

watched as the water filled his small wheat field row by row.

As

I watched, the wind swept down the valley from the heights and brushed

the tender green shoots of the new wheat as a loving father might

playfully ruffle the hair of his small child in passing. It was cloudy

and cool that day, but not unpleasant, and I reveled in the smell of

wet earth and the feel of growing things. As Moha and I waited for the

water to fill his field, we sat on the edge of the ditch, him smoking

a cigarette and me staring at a small earthworm twisting sinuously in

my open palm. Looking at its pale pink skin, at the

delicate

organs and structures at work beneath the translucent surface, I felt

like a small child again, having just turned over a rock in my mother's

garden. Though her garden is 6000 miles away on the other side of the

world, this worm looked no different than the ones I had watched so

long ago.

Above

us the banded mountains soared overhead, and by the river ancient

willows bowed and stooped as if weary from the long months of another

winter quietly endured. At noon, I thanked MoHa for letting me help and

walked the long road back into the village, leaving a trail of muddy

footprints to mark my passage.

On

another afternoon, I leaned against a wall next to a shop and talked

with some older men with whom I have become friends. As we spoke

quietly about the state of the world and the weather, the sound of

singing reached my ears and we all turned to watch as a procession of

children made its way up the street toward us.

They

moved slowly, dressed in fine clothes, and sang a quiet song as they

walked. Most Berber music has a loud, fast tempo and is sung with a

frenetic energy. The song sang by the children, mostly young girls, was

slow and dreamlike—reverent and peaceful, like a dirge or lament.

Above their heads was a human figure dressed in a fine women's jelaba

and, at the back of the group, a small boy held a cross aloft. It was

exceptionally strange, and I had never seen anything like it here

before. Yet it still seemed strangely familiar. I turned to the man

next to me to ask about the procession, which was now even with our

group. "They are calling the rain," he said solemnly. I looked up at

the cobalt sky, cloudless and dry; no rain had fallen in months. I then

gestured to the cross and asked what it was. "Did you not know that

many of the Berber peoples were Christian before the Arabs came and

conquered Morocco?" I shook my head in wonderment and we fell silent

for a time. From questions asked later and from what little I can piece

together of this strange occurrence, what I had witnessed was a Roman

Catholic saint's procession, combined with an ancient Berber rain

ceremony. It was a sight to behold.

The

following day, I went outside to walk and watched as clouds gathered,

towering and swelling on the eastern horizon. The wheat shook in the

fierce winds before the storm and the pale tender petals of new apple

blossoms swirled around me like summer snow. As I reached my door, the

rain began to fall.

Later

that week, I found myself walking through the dirt streets and

alleyways of the old part of the village toward the earthen house of

the family that provided a home for me in those first crucial months

spent here almost a year ago now. My path took me across the graveyard

with its quiet stones protruding from a sea of waving golden grass. A

memory surfaced from the previous year of a small girl with a flashing

smile and beautiful eyes. Kalima. One morning in late summer she simply

did not wake to her mother's touch; she sleeps now beneath one of these

silent stones, marked red with a splash of paint, raw colored like a

fresh wound. Her passing shook us all.

Death

comes as no surprise to the people here; the harshness of this

destroyed place is not lost on the Berbers of the Ait Haddidou. Death

is a constant companion that shadows the children as they play and is

greeted by the stooped and weathered elders as an old friend if

perchance he comes to call. I am sure they would invite him in for tea

and bread if they were able.

A

village near here made national news when nine children died in a

single unrelenting period of cold several winters ago. Paved roads and

power lines followed the tragedy, but countless other villages suffer

in remote silence and families continue to bury their dead quietly and

resignedly, though they may go before their time.

Such

harshness eats at me at times. Even in my terrifying periods of

illness, being weak and alone unable to walk or speak, I was protected

by virtue of being an American. I knew that I could be evacuated at the

push of a button, and on a flight home within a day. There is no such

escape for my friends here. This harshness is their reality; it is all

they know and places outside the Atlas seem like a

I

have made two good friends here in the village, I will call them "Said"

and "Mostafa". They are 18 and 19 respectively, and good listeners.

Spending time with them, I sometimes forget I am speaking another

language and we talk and laugh long into the night.

Some

evenings, they stop by my home to smoke a hookah with me in my living

room. Hookahs are common here and exceptionally well made. Mine was

<<Prev Home PDF Next>>