Authors' note: to avoid 'pronoun confusion' we have referred to ourselves in the third person.

For 40 years, David Brower, the former Executive Director of the Sierra Club, has been a passionate and sometimes controversial leader of the environmental movement; now in his eighties, his impact is still felt. In 1996, Brower eloquently fought for and succeeded in convincing the national Sierra Club board to publicly support efforts to drain Lake Powell, the massive reservoir that in 1963 flooded Glen Canyon in southern Utah.

But in September 1999, as members of the proposed "Glen Canyon Group" of the Sierra Club argued the wisdom of that board decision, a twenty-year member of the Club made a startling accusation. Most members of the group were enthusiastically supportive of Glen Canyon restoration, but not Mike Binyon. As the debate around the table heated up, Binyon dropped a bombshell. "You know how Brower talked the board into passing that resolution don't you? He walked into the meeting unannounced and slapped a check on the table!"

We looked at each other in stunned disbelief. "How much was the check for?" we asked. Binyon replied, "I heard it was for a quarter of a million dollars."

David Brower says it's ridiculous fiction.

For the last eight months, this is the kind of animosity, emotion and deception that has plagued a very frustrating attempt to establish a grass roots activist group of the Sierra Club in southern Utah. How it will ultimately be resolved remains to be seen; how it got this far is the subject of this story.

For almost a century, the Sierra Club has been fighting the construction of dams in the West. In 1913, John Muir, a passionate and eloquent defender of wilderness and the founder of the Sierra Club, learned of plans to dam the Hetch Hetchy River in the High Sierras. Hetch Hetchy was called the "other Yosemite" by many and Muir was determined to save it from flooding. That summer he wrote, "The people are aroused. Be of good cheer, watch, pray and fight."

Muir waged a long and ultimately futile battle to save Hetch Hetchy. Today the river lies buried in a watery grave; Muir mourned the magnificent canyon's death to the day of his own.

It would not be the only canyon lost to the dam and the diversion tunnel and hydroelectric power. In the years and decades to come, countless untamed rivers across the West would be plugged, flooded and destroyed by the Bureau of Reclamation and the Corps of Engineers. In fact, based on a BuRec master plan for the Colorado River Basin in the late 1940s, not a single mile of free-flowing river would have survived their dam-building dementia.

In the early 1950s, The Bureau set its eyes on the Green River at a place called Echo Park near Dinosaur National Monument. The proposed dam was to be the centerpiece of the Colorado River Storage Project, and would have flooded millions of acres of spectacular river canyons. The Sierra Club and other environmental groups opposed the dam, waged a dramatic David and Goliath battle against the Bureau and, to the surprise of many (even them) the Sierra Club won. But as a compromise, the Club agreed not to oppose the construction of another dam at an alternative site---Glen Canyon.

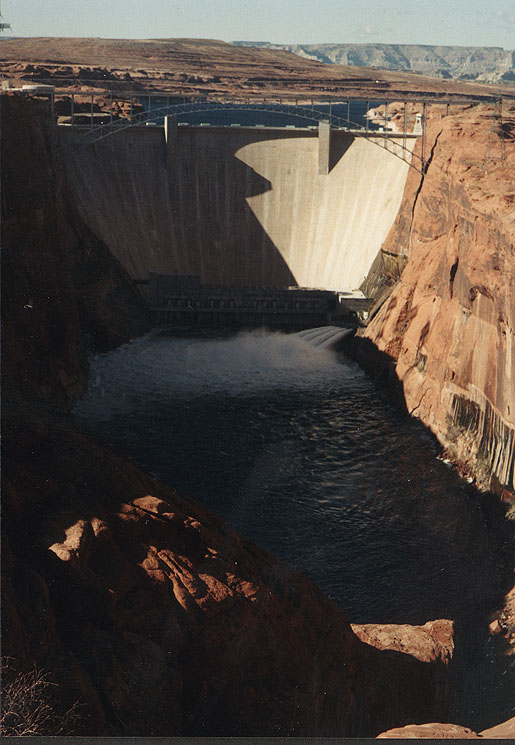

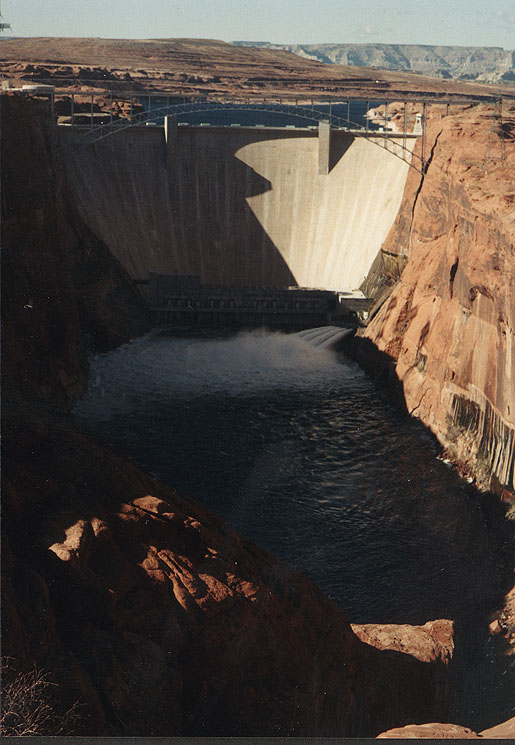

As the great photographer Elliot Porter would lament years later, It was "The Place No One Knew." In the mid-50s, the Colorado Plateau was the most isolated section of the United States and very few had any idea what was there. Months later, when Brower and others made a trip to Glen Canyon to see what they had given away, they were horrified. Construction of the dam began in the summer of 1956 and seven years later, as work neared completion, the diversion gates at the dam were sealed and the free-flowing river in Glen Canyon was cut off. To this day, Brower has never forgiven himself.

The disaster at Glen Canyon would not be forgotten. Only a relative handful of river runners and tourists saw the canyon before the reservoir flooded it all, but the memory of that magic place was emblazoned forever in their hearts and minds. Even as the dam was being built, Ken Sleight helped organize the Friends of Glen Canyon to stop the Bureau from completing its work. But the group lacked the power or numbers to make anything but a token gesture of opposition. Later, author Ed Abbey would make sure that none of us ever forgot this monumental loss of one of Nature's great masterpieces in countless books and essays. And Katie Lee, whose music and stories of those glorious days can just tear your heart out, still actively campaigns for the draining of the reservoir she refuses to call a "lake."

But it all seemed Quixotic, the wild dreams of dedicated dreamers. For those of us who stood at the dam with Ed Abbey 15 years ago and chanted "Drain the Lake!" and prayed for that "precision earthquake" that Abbey was fond of saying, we could take comfort in the justice of our cause, but found little if any reason to hope that our cause might ever be taken seriously.

In 1996, everything changed. Dr. Richard Ingebretsen founded the Glen Canyon Institute (GCI), a non-profit organization dedicated to the scientific and economic examination of the reservoir which, he believed, would ultimately support the de-commissioning of the dam. Ingebretsen, at first glance, seems an unlikely candidate for such a role. A native of Utah and a devout lifelong member of the LDS church, he is nonetheless passionate in his conviction that the construction of Glen Canyon dam was one of the great environmental tragedies of our time.

In October 1996, leading scientists, engineers and Bureau of reclamation officials gathered at GCI's second annual meeting and the ensuing discussions were remarkable. According to Ingebretsen, "it became clear that replacing the reservoir with a free-flowing river...would make water delivery more efficient downstream and eliminate the nearly one million acre feet of water that is lost each year at Lake Powell." As one BuRec engineer put it, "The idea of de-commissioning dams is no longer a crazy idea...it's on the table now."

Two weeks later, on November 16, 1996, the national board of the Sierra Club made an historic announcement. At the request of David Brower, the former Executive Director, now 84, and a board member himself, the national board considered and unanimously passed a resolution to "advocate the draining of the reservoir behind Glen Canyon Dam." The nation's largest environmental group had thrown its support behind a remarkable and visionary idea---to fix a tragic mistake, a mistake for which the Sierra Club itself felt partially to blame.

David Brower came to Utah to present his proposal before a public function sponsored by the Glen Canyon Institute. A standing room only crowd of 1,600 came to hear him speak in Kingsbury Hall at the University of Utah where he outlined this daring proposal.

The proposal was based on the fact that the Bureau of Reclamation studies show almost a million acre-feet, or 8 percent of the Colorado River's flow, disappears annually between the stations that record the reservoir's inflow and outflow. Almost 600,000 acre-feet alone are presumed lost to evaporation. A million acre-feet could just about meet the domestic needs of some 4 million people. Based on present water costs, this is worth hundreds of millions of dollars. A gigantic waste of water!

Brower reasoned that the sooner we begin the Glen Canyon restoration efforts, the sooner the recovery of the beauties of the Glen Canyon--such as the Cathedral in the Desert, Hidden Passage, Music Temple and many other beautiful and enchanting canyons.

Not everyone in the Sierra Club was quick to embrace the Restoration Resolution. In Utah, in fact, the idea was met with downright hostility. Anne Wechsler, chapter chair at the time, wrote an article in the Chapter's newsletter, The Utah Sierran, critical of the national board's policy. Recently, Wechsler made it clear she was expressing more than just a personal opinion. "Since there had been a unanimous vote (by the Utah ExCom) against adopting a policy to drain Lake Powell, I was writing for the Chapter, not myself."

Wechsler traveled to San Francisco to the Sierra Club's annual meeting and appeared before the board to demand that it rescind its position on Glen Canyon. The Chapter believed that it had not been properly consulted before the board acted. But after her remarks, there was not so much as a motion by the board to reconsider its position, and its support of Glen Canyon Restoration remained unequivocal.

In an attempt to resolve differences between the Chapter and National, a "Draft Memorandum of Understanding (MOU) between the Sierra Club Board of Directors and the Utah Chapter" was presented to the Utah Executive Committee (ExCom). In part, the MOU said, "Draining Lake Powell is the one official position of the Sierra Club. The essential central mission of the Task Force is to direct the Club's efforts to implement this policy." Further, it explained that "efforts to promote the draining of Lake Powell should be conducted in concert with...our Utah BLM wilderness campaign and defending the Escalante-Grand Staircase National Monument."

The MOU was discussed by the Utah Chapter on September 14, 1997 and four days later, the ExCom summarily rejected it. Instead the renegade Chapter passed a unilateral "Resolution of the Executive Committee." It said, in part:

"WHEREAS the Executive Committee of the Utah Chapter of the Sierra Club is concerned about the timing of the national Sierra Club's Lake Powell media campaign and negative impacts of the campaign on the Utah wilderness effort...the National Sierra Club should spend no more time, money, or other resources promoting or implementing its Lake Powell policy, and should not participate in any further media events to promote the draining of Lake Powell, until after a good Utah wilderness bill is passed."

The September 18, 1997 resolution claimed that the Sierra Club was in the "embarrassing position of not yet having answers to tough media questions." The Chapter was adamant in its opposition; the national board just as unwavering in its support of the 1996 resolution. It was a stalemate. For years, perhaps even to this day, very few Sierra Club members in Utah even understand that their own chapter leaders are at odds with the Club's national policy. As for waiting until "a good Utah wilderness bill is passed," most political observers concede that passed legislation is years away.

On September 23, 1997, Utah Congressman Jim Hansen called for hearings in the U.S. House of Representatives regarding the proposal to drain the reservoir. Hansen thought it was a pretty goofy idea and believed that congressional hearings would discredit the movement once and for all. Instead, the testimony before the national media gave new credibility to the plan. Evidence of that new-found respect came on March 5, 1998 when Rep. Chris Cannon introduced House Resolution 380 in the House of Representatives expressing the sense that no change in the water level of Lake Powell was justified. Even Utah congressmen were getting jittery.

In the early summer of 1999, as the idea of decommissioning dams across the country became a topic of national debate, and as attention continued to focus on Glen Canyon Dam itself, a group of citizens in Moab gathered one night to discuss the future. It became clear to everyone that here on the banks of the Colorado River, just a hundred miles upstream from the reservoir, that this was the time and the place to create a new grass roots arm of the Sierra Club that stood foursquare behind the restoration policy of the national board.

Beyond the Glen Canyon issue, we were struck by the reality that there is NO grassroots environmental group in southeast Utah that confronts a variety of serious land issues---from the transportation and storage of radioactive waste to issues of runaway growth and development in rural Utah communities, the Sierra Club desperately needed an activist voice in southern Utah.

Although we knew something of the Chapter's reluctance to embrace the national Board's policy on Glen Canyon, it was difficult for anyone to grasp the magnitude of the Utah ExCom's complete intractability. We even discussed the possibility of proceeding as a "stealth group," to disguise or deny any interest in the Glen Canyon Hot Topic until after Chapter approval. But finally it was decided that we were simply incapable of that kind of deception and could only speak honestly and earnestly on all the environmental issues that concerned us. Despite some misgivings the group moved ahead with unbridled optimism. With the group's support an editorial about the proposed new group appeared in The Canyon Country Zephyr.

On July 16, our group met to discuss the future. Since there were groups already established in Ogden and Salt Lake City, we decided to establish another group in southern Utah. We had the necessary 25 interested members needed to proceed and proposed a group that would cover the counties spread across the Colorado Plateau of Utah. These groups would be under the umbrella of the Utah Chapter.

Appropriately, the members voted to call themselves "The Glen Canyon Group" and, in late July, Ken Sleight hand-carried the preliminary paperwork to the Chapter for approval along with a list of officers (Sleight had been elected chair) and concerns that the group hoped to address. They included the need to: "1. Support efforts to restore Glen Canyon. 2. Support efforts for safe disposal of toxic/nuclear waste. 3. Support efforts to increase wilderness in Utah." Other areas of concern included recreation and tourist impacts, commercial logging on public lands, large scale toxic mining and grazing impacts.

On July 30, Ken Sleight wrote to Nina Dougherty, President of the Chapter, and the Chapter ExCom advising them that some of the Moab members of the Sierra Club would be attending their August 2 meeting to plead our cause and that members would be having an organizational meeting on September 7 at Pack Creek Ranch, near Moab. Chapter officials were invited to what was hoped would be a landmark event. The meeting didn't happen...the Chapter would not support it.

On August 2, Ken Sleight, John Weisheit, and Kevin Walker represented the members from the Moab area at the Chapter meeting in Salt Lake City. Each extolled the virtues of the establishment of the new group. Some of the members of the ExCom said they wanted a chance to review a written proposal before they voted. A proposal had already been submitted to the Chapter office previously (hand-carried to them), but the officers failed to distribute copies to the members of the ExCom for their perusal prior to the meeting. Instead we were charged with being a "single issue" group--establishing ourselves just for the sake of draining Powell Reservoir. Even so, we fully expected approval that night, but the Chapter officials delayed the decision to another day. Prospects looked reasonably good even then.

In August, the fledgling group was joined by "longtime Utah Chapter Sierra Club members" from Salt Lake City, Jean and Mike Binyon. Jean had once been on the Chapter ExCom and both Binyons supported the Chapter's 1997 resolution opposing the national board's policy. Now the Binyons attempted to persuade the group to abandon its Glen Canyon restoration priority.

Supporting their position was Utah Chapter ExCom member Dan Schroeder, chairman of the Ogden group. He is also the author of three resolutions which called for the formation of a new group, but which, at the same time, rendered it impotent and ineffective. In an email to the Binyons, in which he added "feel free to forward (this) to others down there who may be interested," Schroeder made it clear that, when it came to the issue of Glen Canyon restoration, there was no room for debate. The new group, if approved, could simply not discuss The Forbidden Topic. In his comments, Schroeder observed, "I and others feel that the name of the group should not be Glen Canyon. I've written "Canyonlands," but you folks may prefer something else and I really don't care, as long as it's not Glen Canyon."

Then Schroeder introduced his restrictive resolutions. For all the same reasons that the ExCom had stated in its 1997 unilateral rejection of Sierra Club's national policy, the most offensive of the new resolutions proclaimed:

"...it shall be the policy of the Utah Chapter of the Sierra Club not to initiate public discussion or debate on the issue of Glen Canyon restoration at this time. 'Public discussion' includes (but is not limited to) press releases, mailings, electronic communications, contacts with media, and events to which the public is invited. Should such public discussion be initiated by the media or other parties, those who speak for the Chapter shall endeavor not to participate in any official capacity. Direct questions by the media may be answered factually."

It was a gag order plain and simple.

The Group would not be allowed to pursue one of its major objectives. It would not even be able to name itself! Members of the group met in an emergency meeting to decide on a course of action. The ExCom planned to vote to approve (or disapprove) the group in a few days, and some Moabites wondered if urging a delay might be the best course of action. Ultimately, however, the Glen Canyon Group decided it was "sink or swim" time. It made clear to the Binyons, who planned to represent the group at the ExCom meeting in Salt Lake City, that the gag order resolution was not acceptable under any conditions, nor would the tampering of the "Glen Canyon" name. Up or Down, we said. Reject us or Support us--it was that simple.

On the evening of September 13, the ExCom voted to approve the Moab group...BUT with the restrictive resolutions intact. The group had been approved, but with no name and no voice. The Moab members (with the exception of the Binyons) were stunned.

The Executive Committee of the Utah Chapter had, in one swift gesture, wielded the power of its office to demolish (for the time being at least) the goals and priorities of the Moab group. The disingenousness of its argument to squash the group is staggering. According to the Sierra Club bylaws, a group cannot take a position that contradicts the policies of a chapter. The Utah Chapter's 1997 resolution opposing public support for Glen Canyon Restoration is chapter policy. To contradict that resolution would therefore be a violation of the Chapter bylaws. In an email correspondence to the Binyons, Schroeder stated it clearly: "The Glen Canyon policy outlined in my first proposed resolution is, I think, merely a closer articulation of the policy we adopted two years ago (the September 18, 1997 resolution).

BUT...the Chapter, by repudiating the national board's resolution on Glen Canyon Restoration violates the Club's national policy. So...the Utah Chapter opposed the Glen Canyon Group because it actually supported the policy of the national board!

In addition to its obtuse and even bizarre logic, the ExCom maintains a bunker mentality when it comes to providing basic information to its members. Numerous requests for membership strength, proposed geographical group boundaries, requests for committee assignments, and concerns about the previously mentioned restrictive resolutions were met, for the most part, with repeated deadly silence. Nothing.

Who does the leadership of the Utah Chapter speak for? Does it truly represent its members? Apparently the Utah leadership wants to keep that information a secret. A few weeks ago, Stiles attempted to acquire two basic pieces of Chapter data. First, how many Sierra Club members are in the Utah Chapter? Second, how many of those members actually voted in the last ExCom election? Each year, the Chapter presents a slate of candidates to its members; the information is conveyed via the quarterly Chapter newsletter (a violation of national bylaws; ballots are supposed to be sent separately to all chapter members.). Votes must be cast by the end of October and the results are posted in the following newsletter.

Well...that's not quite right. The winners are posted, but not the vote tallies. The actual vote totals are not released. And so, in email after email, phone message after phone message, Stiles attempted to attain this information from various members of the Utah Chapter ExCom, its field representative and its chapter representative---they were either met with either silence or obfuscation.

Finally, through the national office, we learned that the Utah Chapter had, as of December 31, 1999, 4358 members and, by way of an anonymous tip from a Utah Chapter ExCom member, that approximately 20 to 30 of those members vote. Subsequently, an email was sent to each of the Utah Chapter members previously contacted that read: "OK...informed sources have told me there are between 20 and 30 voters. If that's wrong, contact me. If I hear nothing I'll assume it's correct." We never heard an official word. In fact, we learned that the ballots had probably been destroyed.

Even if the estimated vote were doubled (recently, one ExCom member believes as many as 50 ballots were cast), the leadership of the Utah Chapter, those who have chosen to defy national Sierra Club policy, not only makes decisions without a mandate, it represents barely 1%, perhaps as low as 0.5% of the Utah membership! Schroeder once proclaimed, "The Club is unusual in being a 'democratic' organization in which everyone gets a say in decisions."

Maybe so. But very little, if any, effort is being made by the chapter to improve the membership's paltry participation in political issues. And it seems to prefer it that way. Where the Club in Utah does seek a lot of participation is in its varied schedule of outings and outdoor activities for members. Indeed, outings rather than activism often seem to be the central focus of the Utah Chapter.

Note: A week before this issue went to press, Stiles finally received a response from Chapter chair Nina Dougherty regarding the number of ballots cast. In part, she wrote, "As I believe you know, we don't have that information. We do not retain it. Our rationale has been that we do not want to affect the morale, nor the continued high level of activism, of our well qualified candidates. Even though all candidates are well qualified, experienced and effective, some have to lose." So, apparently, no one can remember even the approximate number of ballots cast and they destroy them so as to not hurt the feelings of the losers.

By late September, the Binyons were all but ready to quit the group. Working closely with Dan Schroeder, the Binyons attempted to convince the group that a mysterious "Memorandum of Understanding" between the Chapter and the National Board gave Utah the right to publicly withhold support on Restoration (the MOU turned out to be the one REJECTED by the Chapter) and on September 20, in front of six Sierra Club members, Mike Binyon made a startling allegation.

There has always been conjecture about why the national board made its decision when it did and some have expressed the opinion that David Brower, eager to right the past wrongs of the Club, placed heavy pressure on the board to support the proposal. No one can doubt Brower's passion or eloquence on this issue. But now Binyon made his accusation.

As he told his story of Brower's unannounced entry into the national board's meeting and as he described Brower "slapping a check on the table" in front of them, we all looked at each other, slightly stunned, and pushed the matter a bit further. "Are you trying to tell us that David Brower bribed the national board of the Sierra Club to support Glen Canyon Restoration with a check for a quarter million dollars?"

"No, I'm not saying that at all," a very defensive Mike Binyon now answered and it was all backpedaling after that. David Brower was contacted regarding the allegation and we received this response:

"The story about my offering $250,000 to the Sierra Club Board in exchange for an endorsement of draining Lake Powell is false. Who wrote this fiction? Not a penny was thought of, offered, or needed. It was a total delight to me that the president added me to the agenda and the board unanimously thus sought to correct the Glen Canyon mistake it made in 1956."

Subsequent requests from Mike Binyon for documentation to substantiate his allegations have, so far, gone unanswered.

In the next two months, Sleight sent a series of letters and requests to the Utah Chapter. In order to proceed, the group needed information, such as the names and addresses of Sierra Club members in southern Utah, it wanted to become more involved in Chapter activities and committee work, but his requests were completely ignored. And Sleight explained the need to coordinate other environmental concerns, such as the transportation of nuclear waste, with the chapter. "Because we don't have a strong grass-roots voice in southern Utah, I fear we are losing the battle to keep nuclear waste out of San Juan County," Sleight wrote in one letter to Chapter Chair Nina Dougherty. "I implore you to support our efforts to organize this group. Our voice together can be a strong one." And he asked the Chapter to rescind its gag order resolutions. He asked for time at the next Chapter meeting to state the group's case.

The reply from Dougherty was brief. "I understand you have requested 20 minutes on our Oct 4 ExCom agenda. I want to let you know before you come to Salt Lake City for the meeting that this cannot be accommodated. Please submit your concerns and intentions in writing to me."

On October 4, the ExCom held its monthly meeting and Sleight was there anyway. He felt like a Christian walking into the lion's den. Representing the group, Sleight finally got to speak briefly to the Chapter. "As Sierra Club members," he said, "we request that the Utah Chapter follow the policy as laid down by the national Sierra Club regarding the restoration of Glen Canyon. The 'Glen Canyon Group' wishes to follow the directions, policy and bylaws of the national Sierra Club. Our group should not be used as a pawn between the national and the chapter officers because of policy or ideological differences."

But the Chapter still refused to even consider a vote. A month later, yet another Chapter meeting and again there was no action. The Chapter ExCom, however, did schedule a special meeting for November 15 to consider the general mechanics of group establishment. Sleight faxed Dougherty and the ExCom that he would appreciate "a few minutes" on the agenda. He was asked not to come.

In late November, two members of the Moab Group, John and Susette Weisheit, attempted to break the deadlock by negotiating a compromise with the author of the gag order, Dan Schroeder. Schroeder blamed the Chapter's refusal to proceed on two factors: first, the "in your face journalism" of The Zephyr, which had criticized the Utah Chapter's tactics and had printed the restrictive resolutions Schroeder had penned for the ExCom. Second, he was critical of Ken Sleight's inflexible leadership. These, Schroeder claimed, were the major stumbling blocks to group approval.

It put Stiles in a difficult situation. Under no condition could the independence of his publication be compromised as a bargaining chip on the alter of appeasement with the Chapter. Faced with these kinds of demands, he withdrew from active participation in the group. Sleight tried to hold things together, urging his members to stand tough against the restrictive resolutions and efforts to further divide them. All the group wanted from the Chapter was a vote--even a "no" would allow the group to appeal the ExCom's decision to national and it had a good chance of winning, without compromising anything. On December 8, 1999, the ExCom held its monthly meeting, Sleight demanded a vote, the ExCom balked. And Sleight walked. Unfortunately nobody else walked with him. Sleight later resigned from the Sierra Club altogether.

The remaining members agreed to further compromise with the Chapter and submitted to a "facilitator" who, on January 15, met with the remains of the group and with ExCom members in an invitation only meeting in Moab. Afterwards, acting chair John Weisheit proclaimed victory, saying that the "restrictive resolutions had been rescinded," that the "road ahead looks slick," and that the group was now on its way to becoming a reality.

But that's not what happened. At its next meeting, the board not only rescinded the restrictive resolutions, it rescinded the entire group. By a 6-0 vote, the Chapter minutes proclaim, "the resolution passed September 13, 1999, organizing a Moab-area group, is hereby repealed." And instead of the "organizing meeting that Weisheit and the group anticipated in late March, the Chapter now proposed something else. "In order to explore the possibility of either establishing a group in Moab or otherwise increasing the presence of the Sierra Club in Moab," the minutes of the meeting explain, "the chapter will hold a general membership meeting in Moab...No group will be established at the meeting." As one ExCom member said, "I think (the Sierra Club and Chapter) bylaws are restrictive enough to suit the needs of the club."

In August, Schroeder had made it clear--the restrictive resolutions were simply a "clearer articulation" of chapter policy. The chapter bylaws demand that groups adhere to chapter policy. As one Moab member who attended the 'facilitator' meetings in January explained, "I think, the way it was left, we said that we would agree to the bylaws. Period. I seem to remember that, 'We agree to the bylaws,' was the answer anytime anything was brought up with all their (the ExCom) endless web of questions."

Gotcha. The gag order was rescinded but the club policy against publicly supporting the draining of Lake Powell remains intact. The Chapter has abolished any trace of the old "Glen Canyon Group" and is now prepared to start over with its own people in control. In fact, according to one ExCom member, the meeting on March 25 is being planned in Moab by none other than Mike and Jean Binyon, the same people who adamantly oppose the national board's position on Glen Canyon and who made such disparaging remarks about David Brower.

The result is, Moab and southern Utah Sierra Clubbers may indeed be able to call themselves the Glen Canyon Group someday, and they can state the specific wording of the national board's resolution but, according to group members, they still cannot actively or publicly discuss the subject. As Sierra Club group members, they cannot write articles or have meetings about draining Lake Powell. They cannot sponsor restoration-related events. They cannot have a Glen Canyon slide show that discusses draining the lake. They cannot appear on radio or television news programs as representatives of the Glen Canyon Group if the subject is restoration. As one group member said, "It may be two years before we can actually be open about draining the lake." If then.

Why? Why should it take at least two years before the Sierra Club in Utah actively pursues this bold vision of fixing one of the great environmental disasters of all time? There has never been a better time to proceed than right now. Just last month, an 88 page article was published in the Stanford Environmental Law Journal called "Undamming Glen Canyon: Lunacy, Rationality or Prophesy?" It was written by Scott Miller (with a forward by GCI's Richard Ingebretsen) and closely examines the Sierra Club's national policy. The well-documented and thoughtful analysis concludes that the greatest obstacle to draining Lake Powell is not legal, technical or economic, but political.

Indeed.

This is a golden opportunity. The time is NOW for the Utah Chapter to put past differences aside, embrace the national policy of its own organization and allow the free and honest debate on the restoration of Glen Canyon to proceed.

A "general membership meeting" for Sierra Club members in Moab and southern Utah will be held in Moab on March 25, 1999 at the Moab Arts and Recreation Center (MARC) from 1-4pm. You can join the Sierra Club on the web at: www.sierraclub.org

The Zephyr welcomes a response from the Utah Chapter ExCom.