I never planned on a media career. I just stumbled into it in college. Now it's been almost seven years since I started my first unpaid job in broadcasting and a long disillusioning ride since that first experience in the media world.

For years, I had listened to the University of Utah's public radio station, but never made a pledge. When I finally made a generous $20 donation and delivered it to the station, the receptionist and I struck up a conversation and she insisted I apply for a newsroom internship. I had no communications experience (I wanted to study international relations), but I agreed.

Suddenly I found myself in a disorienting world of soundboards, news reports, reel tape and soundproof studios. I observed reporters and helped them research stories for Friday Edition, a weekly public affairs news program. The show covered social, political, environmental and cultural issues. Reporters researched stories for at least a week, interviewed several sources and produced 5-6 minute segments. I observed reporters and helped them with research. I never produced a piece during the internship, but I left with a new major.

Marketing Tragedy

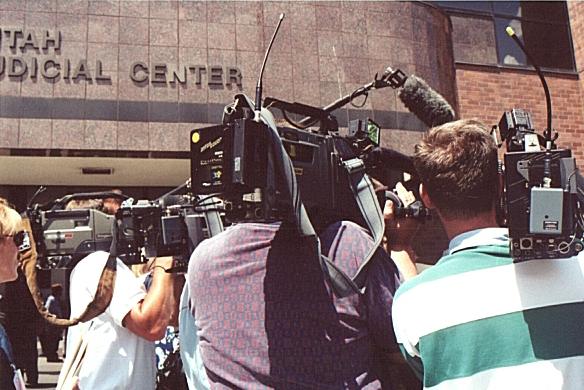

When I later started an internship at a commercial television station, I thought I understood the news business and the elements of a news report, but the contrast between the two newsrooms was startling.

Buzzing police scanners, blaring televisions and frantic reporters replaced the relatively quiet radio newsroom. A little dazed and confused, the managers sat me at the assignment desk (the newsroom's dispatch center) and told me to observe. The assignment editor coordinates between reporters in the field and newsroom producers, listens to police scanners and screens news releases. The assignment editor looked over at me and started to explain his job. He pulled out a white binder and pointed, "Here are the codes to listen for on the scanners: hostage situations, car chases and shootings. Here is a list of state police agencies, call them and ask them if they have any of those incidents happening. Dial 9 to get an outside line."

That was to be my job. They wanted me to call the cops to find the goriest news in the town? Crime reports have a place in news, but I couldn't believe they only did beat checks with law enforcement agencies. I couldn't conjure up the courage to ask dispatchers, "Hi, I'm calling from Channel Z; do you happen to have bloody mayhem, hostage situations or shootings that might make a nice visual for this evening's news?"

I made the phone calls with a watered down script and somehow survived the day. I paid my television dues through more unpaid slave labor and eventually a newsroom hired me to help produce the evening news. I had to log the competing stations' newscasts to make sure our station didn't "miss" a story. Through this tedious task, I realized all the stations aired the same visually motivated drivel. I watched stations lead with the impacts coffee grounds had on your garden to the effects chili peppers had on the common cold.

Most nights the producer would assign me to write the "kicker," the strange or cute video that ends a newscast in hopes of leaving viewers in a good mood. I wrote about everything from a two-headed calf to a gem-studded Barbie to cat fashion shows. Producers chose national and international stories because the visuals were compelling, not because a story was significant to viewers. I learned if the satellite feeds marked "great video" next to a story, I would have to write about it. I was learning to produce a newscast, but I started to wonder if I wanted the skill.

One afternoon I was diligently surfing the web, when a producer swilved around in her chair and said, "I was just watching Channel X, and they did this really nice piece on that family who almost died in a car accident. Could you call the family and see if we can set up something for the later show?" I agreed, picked up the phone and started dialing. I found some relatives who directed me to the hospital. I was feeling pretty good, when I successfully jumped through the hospital loopholes and a receptionist transferred me into the family's private room. The mother picked up. I introduced myself and asked if we could do an interview with them that evening. Frustrated, she said she had been in the hospital all day with her husband and was too tired to talk to another TV crew. I pressed a bit more; she refused again and hung up.

It was not until I hung up the phone that I realized what I had just done. I chased down a family who had just endured a tragedy. At least briefly, I failed to realize that the family's privacy was more important than the credit I would get for getting them on camera. It was a sad story, but was it really news worthy? Was it going to inform people? Did it affect the society as a whole? Did this random event bring to light an overarching societal problem?

The fact is there was no reason for me to call the family, except to get a teary-eyed sound bite from a struggling family. It's like asking the mother whose child has just died, "How do you feel?" The reporter already knows the answer. The goal is to get an emotionally charged response while a camera is rolling. Tears win big bonus points in most for-profit newsrooms.

If invading a family's privacy was not bad enough, there is another experience that I will never justify in my mind. One night the network aired the film, Ransom, with Mel Gibson right before the newscast. It is the story of a wealthy man whose son is kidnapped and held ransom for a large sum of money. The station wanted to keep viewers after the end of the movie. So in a move that proves how blurred the lines between news and entertainment really are, it decided to find a tie-in story to the Hollywood creation.

The only ransom case the newsroom could come up with was a high-profile incident that happened over a decade ago. Producers assigned me to find the archive footage and to interview the now-retired officer who presided over the incident. I put together a short piece and went onto other tasks. Thirty minutes before the news, the station started to tease the piece. The phones started to ring. The kidnapper's family and friends begged us to pull the story. The man had served his time, started a family and was struggling to make ends meet. They told me this was not a news story. There was no reason to rehash something that happened so long ago.

They were right. We were going to publicly reconvict someone, who was trying to start over. The only power I had was to encourage the callers to write letters to the news director. The story ran. I'll never know what damage was done and all this for a few ratings points.

Give them what they want?!?!

And now the biggest quandary in the business: Do you give viewers what they want to know? Or do you give viewers what they need to know? Human tragedy stories appeal to the lowest common denominator: anyone who flips on the local news needs no prior knowledge of the story. The event's randomness gnaws at viewers and keeps them enthralled on a raw empathetic level. The stories are easy to cover and take up few station resources. Law enforcement agencies usually hold a press conference at the scene's location. Hopefully a victim or witness will tell the story from an emotional perspective. The story has all the convenience of a one-stop fast food drive through. Everyone understands tragedy and has some voyeuristic desire to see about it.

But for many of the stories, viewers don't need to know. House fires and car accidents are televisions favorites. Smashed up cars and flames make for compelling visuals but lack substance or depth. If there is no underlying issue why the event occurred, why do stations spend resources covering it?

Commercial space is slowly eroding newscasts. Cable, satellite television and the Internet are all cutting into local news' once-solid audience base. The desire to capture viewers often blurs good journalism with gimmicks and celebrity coverage. So with plummeting audience shares, stations turn to consultants, budget cuts and focus groups to improve ratings and revenue. Stations fire reporters because studies show audiences don't feel comfortable with them. It doesn't matter if the person is a good reporter; it is more important that the audience feels warm and fuzzy when watching the person. When an anchor or reporter is fired from one station, you often see them a few years later on another station. One station's research often contradicts a competitor's.

The Project for Excellence in Journalism, a think tank affiliated with the Columbia University Graduate School of Journalism, studied 49 stations in 15 cities last year. It found that in-depth reporting was the best way to retain an audience. The team gave newscasts grades based on quality: "A newscast should reflect its entire community, cover a broad range of topics, focus on the significant aspects of stories, be locally relevant, balance stories with multiple points of view, and use authoritative sources," wrote Tom Rosenstiel, Carl Gottlieb and Lee Ann Brady in the follow-up article Time of Peril for TV News. (www.journalism.org)

Eye candy, ratings stunts and hype were a sure way of losing viewers. Twenty-eight stations received "A" grades; only one of those stations did not increase viewership throughout the program. The project found the stations with the lowest grades were twice as likely to have plummeting ratings. Local news seems to be moving in the wrong-direction. In particular it is getting thinner. The amount of enterprise, already shrinking, is withering to almost nothing. The amount of out-of-town feeds and recycled material is growing. The majority of stories studied this year were either feeds or footage aired without an on-scene reporter," the authors cited.

It also found local TV was ignoring entire sections of the population: "Out of 8,095 stories studied this year, only seven concerned the disadvantaged. By comparison, 336 concerned entertainers. Over three years, and some 25,000 stories, only 35 focused on the needy." The group of news and research professionals studied around 4,000 stories found that only 0.9% or 36 stories were investigative pieces, only 30 stories included a substantive questioning of sources on camera.

How does Salt Lake Measure Up?

On May 10, I videotaped the four local networks KSL (Channel 5), KTVX (Channel 4), KUTV (Channel 2) and KSTU (Channel 13) to see how their evening news casts measured up. Fox News, Channel 13, is an hour-long program at 9 p.m. To be fair, I only watched the first half-hour because the other stations program only 30 minutes an hour later. The date was chosen at random, so the study was far from comprehensive. All the stations led with the same thing: the Dalai Lama's arrival in Utah. All the stations except KSL (NBC affiliate) comprehensively covered who he is and why he is in exile from his native Tibet. KSL briefly addressed the Buddhist leader's history. The station covered only what happened that day and didn't go into the story's background. It was also the only station that did not interview members of the local Tibetan community.

The stations were all guilty of promotional gimmicks. Web sites, upcoming programming and the morning show promotions are now built-in parts of newscasts. Fox News did a story on dwarfism and the plight of "little people." Half of the story was shown during the first half hour. The second half aired in the last 30 minutes, but was promoted at every break. It was a well-done, interesting story, but the promos got to be a bit much.

KSL pointed viewers to their own website and an article appearing in the next day's Deseret News. It also did a mini-story on an interview airing the next night with Steve Young and his new family.

KUTV (CBS station) has the mother of all toys: a news helicopter. I'm not sure which stories would be fundamentally improved by aerial shots, but this evening the best thing it could come up with was a shot of long-time anchor Michelle King watching a soccer game. Similar to KSL, it also had a promo for an interview with another Utah favorite: Donny Osmond.

KTVX (ABC affiliate) in its first block did a story on sick foals in Kentucky. An interesting story, but I wonder if they would have covered it if they didn't have footage of a baby horse surrounded by doctors in a hospital bed. There was also a segment called, ““Tomorrow's Headlines,”” which shows which stories would lead tomorrow’s newspapers. This evening the top stories were Boeing’s move to Chicago and Timothy McVeigh’s delayed execution. Couldn’t they have just reported those stories, instead of wasting time showing newspaper headlines?

Here are some of the other stories the stations covered: an electrical fire at a Salt Lake restaurant (would this be newsworthy if it happened in St. George?), a water main break at the airport, a home break in and a new cancer pill. The stations also did some memorable pieces: Channel 5’’s Ed Yeats did an in-depth report about a program at the Huntsman Cancer Center, which helps kids cope with dying or sick parents. There were several elements to the story and Yeats interviewed around eight sources. It was a human-interest story, but it was comprehensive and well done. Fox’s dwarfism story touched an often-ignored segment of the population. Channel 4 explored the plight of a couple who wanted to take care of foster children, but couldn’t because the husband carried a concealed weapon. It examined issues of gun rights and child safety. Each station had a combination of quality news and gimmicky stunts. Weather does seem to get more time than any one story.

Moving On

I finally quit the full-time TV job. I am relieved I no longer have to write about two-headed calves. I don’’t watch the local TV news anymore. I listen to the radio and read newspapers. But television is still the most accessible medium and if its news doesn’t comprehensively cover the community, most of the population will not be informed. With voter apathy at an all time high, it is frustrating that TV news has to a large degree cut out political, social and environmental issues. The only story covered outside of Wasatch Front was a million dollar fishing contest at Lake Powell.

I have watched newscasts from several years ago, where reporters went to southern Utah to cover the practice of chaining and the corruption behind the proposed Book Cliffs Highway. Television reporters used to use this paper as an investigative reporting source. The stories were several minutes long and incorporated many sources. Now, these topics would not make it on the news radar screen. They are not ““sexy”” enough and cannot be covered in two minutes. The ratings game is killing quality media.

Recently, the station that got me into this business has been caught red handed in the ratings charade. After 40 years of dedicated work, KUER unceremoniously gave classical music announcer, Gene Pack, two days notice to vacate his show. The man who helped start the station was relegated to voicing promotions for arts and culture events in Utah. The station replaced his unique, one-of-a-kind program with syndicated national programming. Another public radio station, KCPW, already airs most of the new programs. Just weeks after the change, KUER bought bus ads reading, “Hear the world from a familiar voice.” I’m confused.

The station insists the decision was 3 years in the making, but it failed to tell members with open checkbooks. After I left the station, Friday Edition was cancelled. Later it was replaced with a more regional program called Radio West. Now, I’m hearing promotions that this local program is going to start airing at 11 a.m. right in the middle of Pack’s show. The decisions look like crisis management for a station which refuses to acknowledge it made a mistake.

I don’t know what to make of these debacles. It is hard to remain idealistic in light of the current media situations. Educating the public is no longer the number one goal of news organizations. Thomas Jefferson once said, "People cannot be safe without information.

Which just goes to prove that what you don't know can hurt you.