Jack Burns:

An Abbey Fictional Character From Two Dimensions

By Scott Thompson

Several

examples from The Brave Cowboy stand out. Consider this conversation

between Burns and a police booking offcer following his arrest for a

fght in a local bar:

“We might expect a peculiar change in the mentality of the world in the next fifty to one hundred years.” – Carl Jung, 1929

“‘What’s

your address?’ said the booking offcer. ‘I don’t have none,’ Burns

mumbled hoarsely. ‘You got to have an address.’ ‘I don’t. I just wander

around wherever I feel like.’

I

believe that Jack Burns, a character in several of Edward Abbey’s

novels, is in effect a time traveler from the pre-agricultural world.

The hunter-gatherer societies that inhabited that world thrived for

well over 100,000 years and constituted the basic environment of human

evolutionary adaptation. In duration they dwarf the last 5,000 years of

agriculture-based human civilization (“syphilization” is what Ed

called it.)

I

also believe that humanity is destined to reclaim salient features of

those pre-agricul-tural societies, whether we do so by our own choice

or because we are hammered into it by a long series of ecological

disasters.

So Jack Burns is also a time traveler

…

‘What’s your occupation?’ asked the booking offcer.

Burns looked at him. ‘Cowhand,’ he said; ‘sheepherder; game poacher.’

‘Which is it?’

‘All of them. What difference does it make?’

The booking offcer typed for a minute. ‘Where’s your papers?’ he said.

‘My what?’

‘Your I.D. – draft card, social security, driver’s license.’

‘Don’t have none. Don’t need none. I already know who I am.’” (pp.71-72)

from humanity’s future.

He

frst appeared in Abbey’s 1956 novel, The Brave Cowboy: “He was a young

man, not more than thirty. His neck was long, scrawny, with a sharp

adams-apple and corded muscles; his nose, protruding from under the

decayed brim of the [cowboy] hat, was thin, red, aquiline and

asymmetrical, like the broken beak of a falcon. He had a small mouth

with dry lips, and a chin pointed like a spade, and his skin, bristling

with a week’s growth of black whiskers had the texture of cholla and

the hue of an old gunstock.” (p.6)

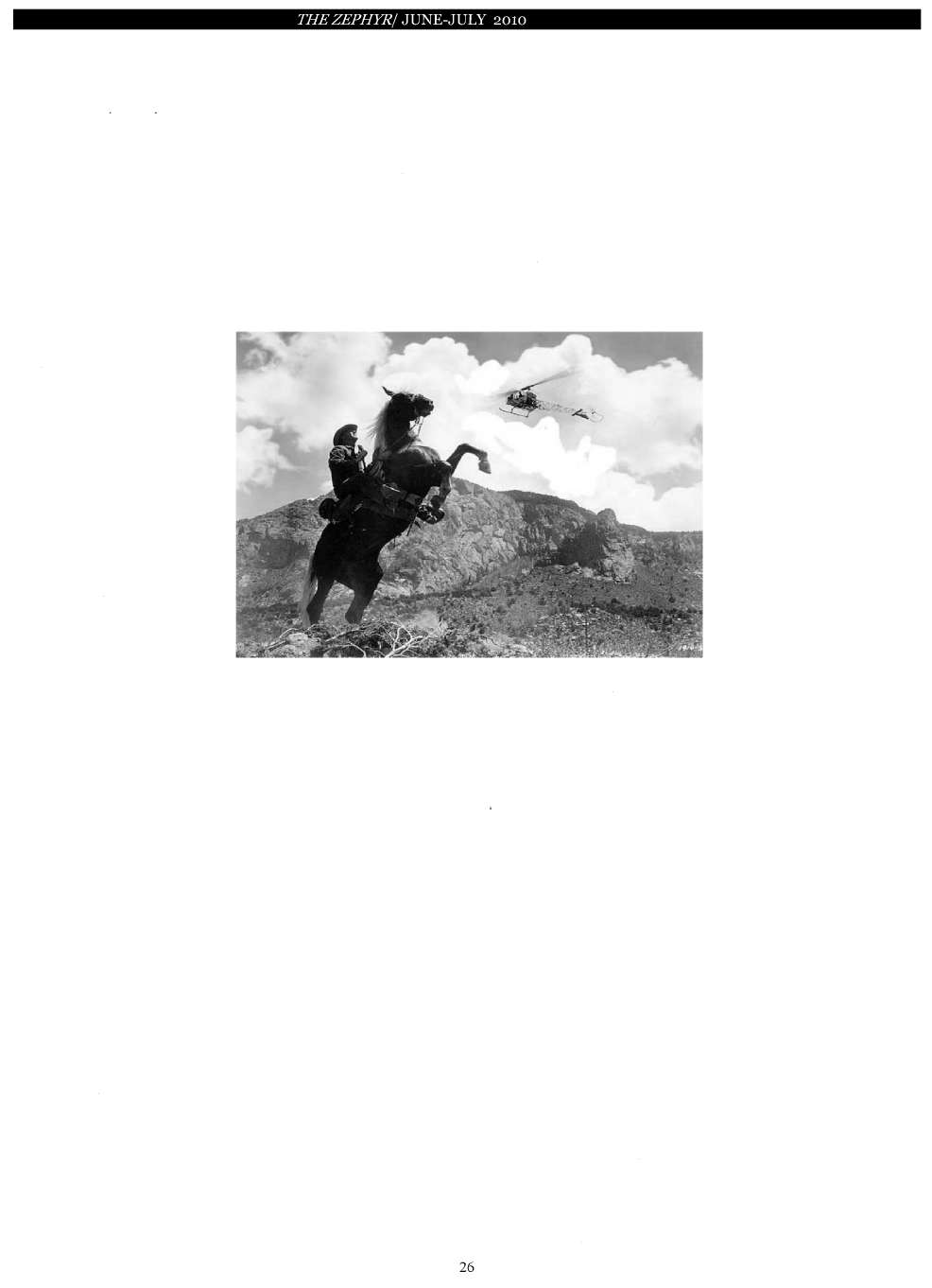

In

the novel Burns rode his temperamental mare Whiskey into Duke City,

New Mexico, in order to rescue his close friend Paul Bondi from jail,

where he was sent for refusing to register for the draft. Burns

engineered his own arrest in order to help Paul break out, but his

friend had already decided to serve out his sentence. Burns then

escaped on his own and outran the

Imagine

what it would feel like to shred every card you have in your wallet:

credit cards, voter registration card, library card, driver’s license,

social security card, professional membership cards, and so on.

Imagine how doing that would affect your way of life and how it could

alter your subconscious picture of who you are.

I’ve

had dreams myself about beginning to accomplish something important

and then losing my wallet and going into a panic. Our collectively

defned identity has a powerful grip on us.

Sheriff

and his deputies on a local mountain range, only to be crushed by a

tractor-trailer loaded with privies when Whiskey panicked crossing a

highway at night.

Abbey’s

1980 futuristic western Good News was set in Phoenix following the

collapse of the dominant political system. Burns was a one-eyed old

man, once again on a rescue mission. He and his Hopi friend Sam Banyaca

rode into the smoldering ruins of the city to fnd Burns’ son, an offcer

in the army of a local tyrant who sought to re-establish a mass

hierarchical social order. Burns failed to persuade his son to leave

and was promptly shot down in an impulsive attempt to kill the tyrant,

once his son had refused. Oddly, Burns’ body vanished before the

tyrant’s soldiers could bury it.

Here is a dialogue in the jail between Burns and his compadre Paul Bondi:

Bondi: “‘…I composed a little pledge or prayer…Would you like to hear it?’

Yes,’ Burns said.

It

went like this: “I shall never sacrifce a friend to an ideal. I shall

never desert a friend to save an institution…Great nations may fall in

ruin before I shall sell a friend to preserve them…”’.

…

I’ll not argue it,’ Burns said; ‘I like it; I think I thought of it before you.’” (p. 109)

I believe that Jack Burns,

a character in several of Edward Abbey’s novels,

is in effect

a time traveler

from the pre-agricultural world.

Group

size matters. I suspect that when an organization is large enough to

start issuing membership cards, that’s when – strangely - it’s at risk

of selling out its own members.

Such

behavior by large groups is unfortunately commonplace, and that may be

a reason why mass societies are flled with disillusioned people, and

also why their institutions are plagued by chronic public mistrust.

Examples: (1) an ethical employee reports misconduct within a

corporation or non-proft agency and is fred and scapegoated in order to

protect the organization’s public image; (2) a professional

organization undermines its own objectivity by taking huge sums of

money from pharmaceutical companies, despite the earnest protests of

its more alert members; (3) legislators who are supposed to rep-

So: two novels, two rescue attempts, two failures. And Burns was killed, or apparently so, both times.

Usually, that doesn’t make for a memorable character.

Yet

there was something about Burns that was strangely appealing and also

disquieting: for example, the way Jerry Bondi, Paul’s wife in The Brave

Cowboy, reacted to him: “She was having trouble with her thoughts; this

man Burns, whose mere physical presence was so reassuring, and whose

love and loyalty she could never have doubted, yet made her feel for

some reason a shade uncomfortable: in his sombre eyes, in his slow

smile and the lines of his face, in the frm rank masculinity of his

body, she thought she perceived a challenge. A challenge in his every

word, every motion.” (p. 30)

Perhaps

she had such a pronounced reaction to him because he possessed ancient

human qualities that rang true on an intuitive level, but that

threatened to demolish her social conditioning. Qualities that

contemporary urban literary critics (“literary crickets” is what Ed

called them) were much too dense to fathom.

I’d like to discuss some of these qualities.

Burns was striking in that he had no emotional connection to the abstract notions and institutions of the mass culture that surrounded him. It was not that he was disloyal to them, strictly speaking: he was not a card-carrying rebel or revolutionary. Such institutions were simply

irrelevant to him.

resent

the public’s best interests consistently give priority to the demands

of lobbyists for multinational corporations that fnance their election

campaigns.

By

contrast, pre-agricultural societies were comprised of small bands,

typically made up of only a few families. It has taken me a long time

to appreciate how resilient and emotionally healthy such a seemingly

frail social framework is. This is because the well-being of an

individual member of the group is much more likely to be congruent with

the well-being of the group itself, and because the leaders are less

apt to be emotionally distant, hierarchical fgures. So that the people

are far more likely to trust them. Deeply.

Burns

was striking in that he had no emotional connection to the abstract

notions and institutions of the mass culture that surrounded him. It

was not that he was disloyal to them, strictly speaking: he was not a

card-carrying rebel or revolutionary. Such institutions were simply

irrelevant to him.