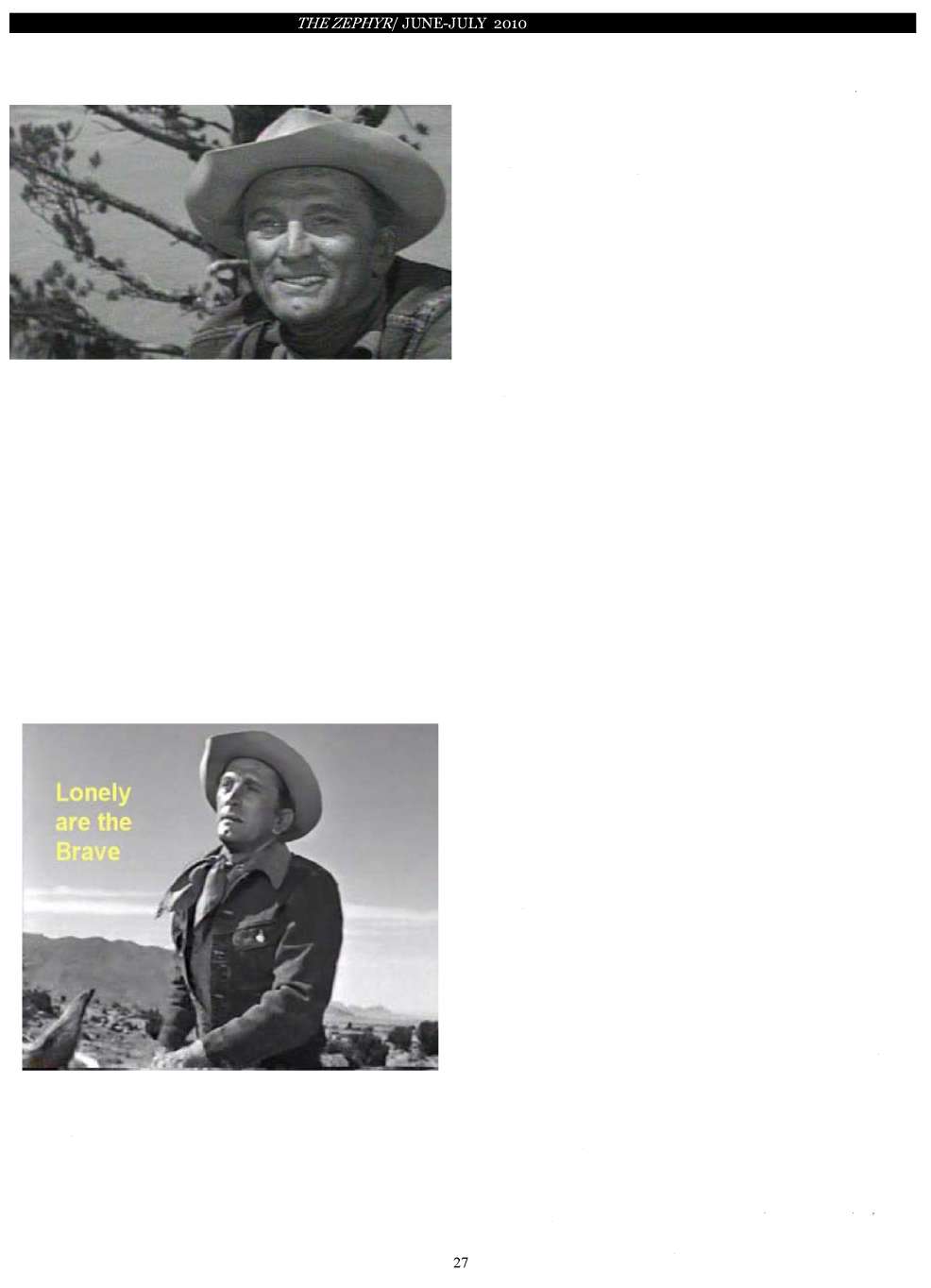

version,

Lonely are the Brave, aptly depicts the result: the Sheriff pursuing

Burns has a visceral contempt for his own compliant, lazy deputies,

while admiring Burn’s boldness - in spite of himself.

But what does cutting through the expanse of barbed wire mean if it isn’t just simple-minded defance? What else is involved?

A

peculiar clue comes from the following conversation between Burns and

his amigo Sam Banyaca toward the end of the novel Good News:

That is the key.

Burns seemed to know this.

The following scene from The Brave Cowboy is relevant to dealing with these organizations:

Banyaca:

“‘…Listen, boss, I learned one thing at Harvard. There’s one thing

wrong with always fghting for freedom, and justice, and decency. And so

forth.’

Burns looks up at the blazing sky. ‘Only one thing? What’s that?’

‘You almost always lose.’

The old man laughs, reaches out, and squeezes Sam’s near arm. ‘Well, hellfre, Sam, what does that have to do with it?’” (p. 222)

The

remarkable thing about Jack Burns is that he was indifferent to both

the ideological claptrap that keeps the mainstream growth n’ proft

system going and the ideological claptrap of leftist social activism

(“chickenshit liberalism” is what Ed called it). Which also refuses to

see the big picture.

Put

another way, there’s a canyon between doing what one can to change the

system – that’s always vital - and expecting to get results on some

kind of focused schedule. As a pre-agricultural person, Burns was all

about the former and had virtually no concern about the latter.

This

is a key point. Pre-agricultural humans were not liberal activists; the

difference is that liberal activists can be as impatient to enact their

social agendas as corporate CEOs are to jack up their quarterly profts.

When we contrast the worldview of hunter-gatherer societies to that of

our own culture, we see that the thinking of our liberals and

conservatives is much closer than we usually imagine. Compared to

either of them, hunter-gatherers might as well have been living in

another solar system.

Briefy,

here’s why. When our forbears became farmers, they got enmeshed in time

lines: that is, when the rains were due, when to plant the crops, when

to harvest them, and so on. And later on with market prices. In

industrial and technological societies, this has escalated into a

bizarre fxation on numbers and clock time: on productivity, quarterly

profts, and election cycles. Time is money and results are everything.

People living in this box are obsessed with short-term accomplishments

and can’t see outside the lid.

Group size matters.

I suspect that when an organization is large enough to start issuing membership cards, that’s when –- strangely ---

it’s at risk of selling out

its own members.

“When

the arroyo turned he rode up out of it and across the lava rock again,

through scattered patches of rabbitbrush and tumbleweed, until he came

eventually to a barbed-wire fence, gleaming new wire stretched with

vibrant tautness between steel stakes driven into the sand and rock,

reinforced between stakes with wire staves. The man [Burns] looked for

a gate but could see only the fence itself extended north and south to

a pair of vanishing points, an unbroken thin stiff line of geometric

exactitude scored with a bizarre, mechanical precision over the face of

the rolling earth. He dismounted, taking a pair of fencing pliers from

one of the saddlebags, and pushed his way through banked-up

tum-bleweeds to the fence. He cut the wire – the twisted steel

resisting the bite of his pliers for a moment, then yielding with a

soft sudden grunt to spring apart in coiled tension, touching the

ground only lightly with its barbed points – and returned to the mare,

remounted, and rode through the opening, followed by a few stirring

tumbleweeds.” (pp. 11-12)

Have you noticed that when you’re

damn straight enjoying yourself, clock time vanishes?

That’s when there’s a glimmer of

the pre-agricultural world.

Conversely,

pre-agricultural people had no concern about measuring time. They were

not in a hurry, because their universe was a timeless now. For that

reason seeing a thousand years in a glance was a simple matter for

them. They would marvel at our inability to do it.

In

such a glance the frst thing that becomes apparent is that our

massively expanding economic system, as presently constituted, is

absurdly unworkable; that it’s as ephemeral as a thunderstorm. The

thought of taking such a system seriously would make them shake their

heads or burst into laughter.

The

danger of our gotta-get-it-done tradition of social activism is that

the fip side is despair. We’re tempted to give up or compromise when

we can’t identify a near-time causal sequence that will give us

satisfactory results. That’s one of the prices we pay for our

obsessive time-consciousness. No wonder when Sam raised the issue of

losing, Jack Burns said, “Well, hellfre, Sam, what does that have to do

with it?” Giving up or compromising weren’t options for Burns because

they weren’t in his paradigm.

At

this juncture in our struggle against global warming, Jack Burns may be

a useful fgure to contemplate. Partly because of his willingness to

persist against superior, if not overwhelming, odds. To that degree,

many a devoted activist can identify with him. But what made him unique

is his exuberant indifference to results.

Burns’

activist-like behaviors, if we can even use that term, did not arise

from a commitment or some personal objective. It was primordial

compared to that: he was simply living in the way that he enjoyed, and

was willing to be killed in order to continue living that way. That

abandon was what gave the man power, and was also what made liberal but

conventionally-minded people like Jerry Bondi uncomfortable with him.

Have

you noticed that when you’re damn straight enjoying yourself, clock

time vanishes? That’s when there’s a glimmer of the pre-agricultural

world. We also get feeting glimpses of it through comedy, which

utilizes absurdity like a blowtorch to reveal the truth.

Jack

Burns showed us how to cut through the barbed wire - which is our own

discouragement and the temptation to compromise - and keep on riding.

To

me, cutting the rigid extension of barbed wire is a metaphor for

severing our emotional ties to the self-serving, sometimes

self-destructive, norms and proclivities of large, collective

organizations (as opposed to violating property rights in a literal

sense.)

I

think it’s signifcant that in this scene Burns pulled out his fencing

pliers only after he’d tried to fnd a gate. This suggests that he was

willing to function within the structure of mass systems as long as he

could pursue his way of life: as he put it, to “wander around wherever

I feel like.”

But

for each of us, as was the case for Abbey himself, the moment of

confict arrives when the expansion of the system’s functioning closes

off all the gates, and when obeisance to that system means that

something inside us will die.

What

then? Our culture only offers its beaded string of threats: don’t make

waves, don’t bite the hand that feeds you, you gotta go along to get

along, don’t be a trouble maker. But if we do give in a lassitude

begins to work its way through us like a fungus. The movie

SCOTT THOMPSON is a regular contributor to The Zephyr. He lives in Beckley, WV.

Join the Zephyr Backbone

and receive a complimentary signed copy of

Brave New West

By Jim Stiles