<<Prev Home PDF Next>>

Gaining Perspective:

Two years in The Kingdom of Morocco...

From Durango & the NPS to Peace Corps volunteer...an introduction to life in africa From Charlie Kolb

It’s

coming on the end of August, and it seems as though fall has already

arrived here in the High Atlas Mountains. Looking out from the roof of

my cement house in the mornings, nursing a cup of coffee, I am often

struck by how much these striking and austere mountains remind me of my

home in the southwest. They resemble no area in particular, but I

sometimes catch an echo of something; that wet dusty smell after a rain

or maybe the way the light makes the mountainsides glow each night at

sundown; an imperceptible resonance of home. Or perhaps that’s just the

wishful thinking of a desert rat far from his territory. According my

journal, I am about 200 days in to my Peace Corps Service here in

Morocco, with just over a year and a half to go before I can come back

to the Southwest and my hometown of Durango. But as the days pass, I

learn more and more; not just about Morocco, but about the Southwest,

and myself as well.

the

native people of Morocco; some had been here for millennia. Would I end

up in a village like that for the duration of my service? I had no

idea what was to come, because, at that point, I still had two months

before I was assigned my “site”, the village I would call home for two

years.

My

training few by, and I enjoyed two glorious months of spring in the

Dades valley, just north of the Sahara. I lived with a family in an

earthen house, eating my meals with them and spending my days in

another house with other volunteers. We were learning the “Tamazight”

dialect of Berber, called “Tam” for short. Tam is a diffcult language,

especially coming from English. The frst night I spent with my host

family, I had no idea what was going on. All I heard was a series of

guttural sounds that I struggled to identify

as

language. Even the year of Navajo I took in college hadn’t been this

daunting. Language was not the only hurdle of training and I found

myself ill more than once, a situation made even less fun by having to

learn to use a “squat toilet”. But day by day, things became easier and

I began to adjust to and even enjoy my time on the edge of the Sahara.

In

early May, training had ended and I had been sworn in as a Peace Corps

Volunteer in the city of Ouarzazate. Now I was standing in the town of

Rich ready to make the fnal move to my site. I lugged my duffel bags up

to a dusty van called a “Transit” and handed them to a wiry kid on the

roof, who proceeded to tie them down. I clambered inside and sat down,

feeling the silent gaze of roughly 15 Berbers rest on me with intense

curiosity. Even though I had done well in language training, I still

felt that I understood very little, and could think of nothing to say.

I looked around me; my blue eyes met the brown eyes of the other

travelers. The men were

So

let me begin at the beginning, and tell you who I am and where I am

coming from. My name is Charlie Kolb and I grew up in Southwest

Colorado. I have been exploring the canyon country for as long as I can

remember and hope to spend the rest of my life doing the same. I have

worked the past 3 years as a Ranger for the National Park Service, and

it is this vocation that led me to the Peace Corps. Well, at least, it

gave me the justifcation I needed to sign up. The Peace Corps offers a

magic carrot called “Non-competitive Permanent Eligibility,” which

essentially means that any individual who serves two years abroad in

the Peace Corps is eligible to be hired into any permanent position

he/she/it qualifes for—with no competition or red tape. So, in short,

I found that I needed to move to Africa for two years in order to fnd

the job that would allow me to stay home. One thing led to another and,

over a year after my initial glance at the Peace Corps’ offcial

website, I found myself on a plane to Casablanca.

dressed

in ankle length robes, or jelabas, in varying shades of white, grey,

and brown. Some wore small turbans of white or yellow cloth wrapped

tightly around their heads. The women wore loose cotton dresses, and

some held a bedsheet around their shoulders—a lighter substitute for

the traditional striped cloak. Their dark headscarves were draped over

their hair and secured in a series of elaborate knots by a narrow cloth

of pink, white, or red. I was dressed in jeans and a t-shirt and I felt

very pale. Once the transit flled, and several people climbed on the

top to ride, we set off on a fve-hour journey up into the mountains.

Looking

through the sheaf of “motivation statements” that I wrote to the PC

before I had any idea of where I was going, I see that my primary

reason to join the Peace Corps was to “gain perspective”. In the past

six months I have surely found that. I have gained perspective on my

new country, Morocco, perspective on my home in America, and unique

perspective on Islam—a religion that many Americans do not understand,

or even wish to.

Stepping

off the Royal Air Maroc jet in Casablanca, I had no idea what to expect

of this new and mysterious place and neither did the 60 or so other

Peace Corps Trainees who were milling around me. My head was spinning

as we rode a bus for hours across the plains from Casablanca to

Marrakech. I had just left behind 4 feet of fresh snow in Colorado, and

suddenly I was looking out over felds of new wheat, interspersed with

palm trees, and countless tiny villages clustered around the pale

minarets of mosques. We

My site is a small, remote village whose name

I am not allowed to mention in print, and from the frst moment

I stepped off of the transit in middle of the dusty square,

I have been in love with this place.

It is one of the coldest sites in Morocco...

It’s

coming on the end of August, and it seems as though fall has already

arrived here in the High Atlas Mountains. Looking out from the roof of

my cement house in the mornings, nursing a cup of coffee, I am often

struck by how much these striking and austere mountains remind me of my

home in the southwest.

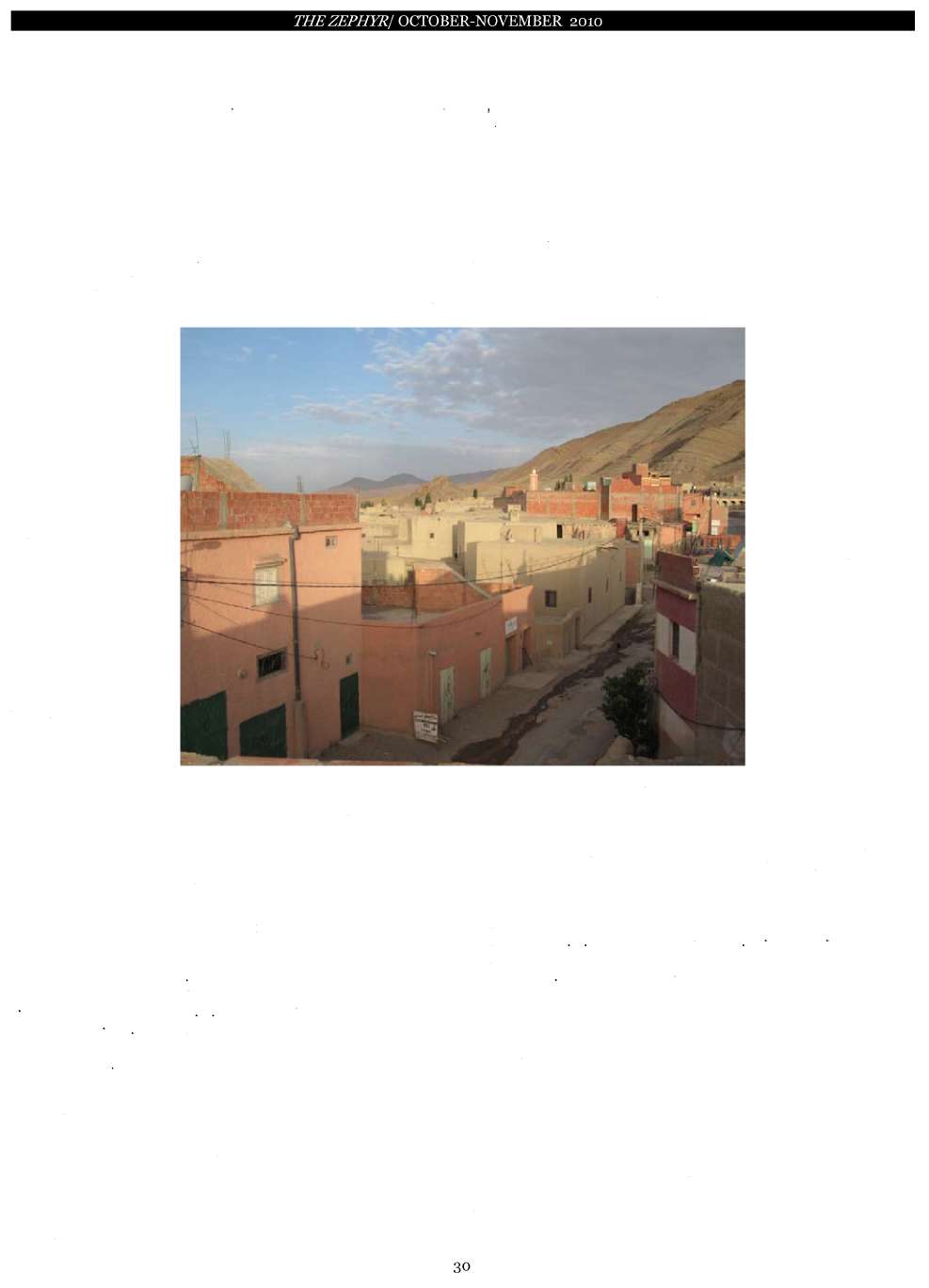

My

site is a small, remote village whose name I am not allowed to mention

in print, and from the frst moment I stepped off of the transit in

middle of the dusty square, I have been in love with this place. It is

one of the coldest sites in Morocco, and I have been told that, like

Colorado, it is mild in the summer and icy in the winter. It receives a

substantial yearly snowfall and the roads are often closed. Sounds

perfect.

spent

that frst night in a walled hotel being eased into the experience. Even

in the insular environment of the hotel, everything seemed foreign; the

tiled walls, the food, the accented English of the staff members, who

were mostly Moroccans themselves. Everything was strange to all of us.

I fell asleep that frst night on a brocaded couch surrounded by people

I did not know and in a country that I did not yet understand.

We

rode through the Atlas the next morning, on a pass called

Tizi-n-Tichka. It was tortuous and high and I enjoyed looking over the

edge into the deep valleys or up to the icy summits high above. It

seemed to frighten some of my fellows, but reminded me strongly of the

steep passes back home in the Southwest. Villages of earthen huts

surrounded by terraced felds clung to the mountainsides. We were told

they were populated by Berbers,

The

people here are a Berber tribe called the Ait Haddidou and they are one

the most ancient in Morocco. Islam, here in the valley, is a “recent

development”. So, while we do have power, water, and access to

rudimentary medical services, the old still retains a very strong

presence alongside the new. Men in jelabas walk side by side with boys

dressed as if they were transported forward in time from the 80’s.

Peugots trundle up and down the hill in the center of town, passing

mules and donkeys laden with crops harvested from the felds or plants

gathered in the mountains.

This

all comes together once a week at the market or souq, which is a blur

of sounds, smells, and colors. People come into the village from

surrounding communities; many