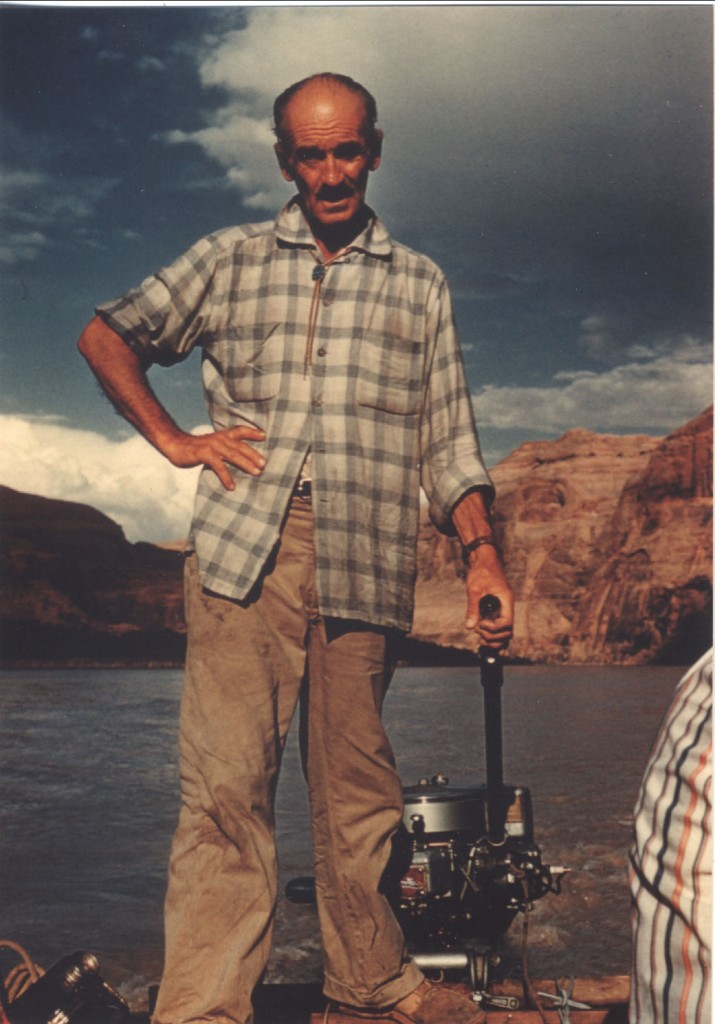

This is the story—a sort of historical sketch—of one of my most adventurous friends. Though she would join me on many trips—about 40 of them—from 1962 to 1979, I had never heard of Edna Fridley when Harry Aleson met me for dinner in 1962. Harry and I met in Salt Lake City for food and good old river talk. His pending Yukon River trip took top billing. I planned such a trip in a few weeks too. While chatting, Harry said he wanted to go to Brigham City to see a client of his who had taken a number of trips with him in Glen Canyon. He asked if I wanted to go along. Thank goodness I said yes. I jumped into his Dodge power wagon and off we went to Brigham.

This is the story—a sort of historical sketch—of one of my most adventurous friends. Though she would join me on many trips—about 40 of them—from 1962 to 1979, I had never heard of Edna Fridley when Harry Aleson met me for dinner in 1962. Harry and I met in Salt Lake City for food and good old river talk. His pending Yukon River trip took top billing. I planned such a trip in a few weeks too. While chatting, Harry said he wanted to go to Brigham City to see a client of his who had taken a number of trips with him in Glen Canyon. He asked if I wanted to go along. Thank goodness I said yes. I jumped into his Dodge power wagon and off we went to Brigham.

As we drove, Harry told me a little about Edna Fridley, a woman who loved Glen Canyon as much as we did. Edna and her husband Charles made their home in Brigham City. Their daughter Martha attended school and Charles worked for Hercules. A whiz at computers, Charles seemed to enjoy his job. I don’t know if they knew then that they would stay so long in Utah.

Edna, inviting us into their well-kept trailer-court home, seemed glad to see us. Harry introduced me and she and I talked for quite some time about the canyons. Charles supported Edna’s sense of adventure. His wry sense of humor matched Edna’s. It certainly attracted friends to them, and I enjoyed talking with them.

I had known Harry for some time. At his invitation, I often camped with his small groups in Glen Canyon. Often, because of Harry’s failing health, we joined together for conjoint trips in Glen. We both benefited from the arrangement. Harry met a lady named Dottie on one of his trips, and, before long, they set a marriage date and a wedding site at Lost Eden Canyon. They wanted one last and marvelous trip before the reservoir encroached behind Glen Canyon dam. Edna Fridley and I were both members of the wedding party. I came late, having taken my own boat to meet our friend Bill Wells, the Flying Bishop of Hanksville, and carry him across river to the wedding site. He was to marry the couple.

We all hiked up to the ceremonial site in Lost Eden in front of a beautiful pool of water. The wedding proceeded without a hitch. After the jovialities and best wishes, I chatted with Edna Fridley for some time, and she gave me a rundown on things. She’d be with Harry and Dottie for the remainder of their trip. It was the last trip for her before the filling of Glen Canyon by the reservoir behind the dam. The reservoir would destroy the canyon as she knew it. I told Edna that I’d be taking Escalante “hiking with pack stock” trips the following year to explore areas not yet desecrated. Later, I sent Edna some homespun brochures, and she excitedly signed up for an Escalante trip.

The dam’s effects thrust my mind into an upsetting quandary. The reservoir rose at such a rapid rate that God-given treasures faced destruction each day. The reservoir flooded and destroyed many beautiful side canyons and grottos, thousands of ancient Indian ruins and writings, and even the majestic Music Temple and Hidden Passage. For a brief spell, I had thought of escaping north to the peaceful and quiet country of the Yukon. But, as I camped on the river sands, I concluded that I needed to continue to be close to the land I treasured, in spite of the dam.

At this point, I moved my family to the town of Escalante, one of the most out-of-the-way places in Utah, to be closer to an incredible river canyon system. Abandoning my former transport of river rafts, I climbed astride my horse to see the remaining enchanting canyons not yet affected by the rising waters. I carried the food, gear and personal duffel by horse and mule pack.

Escalante had been very young village when the legendary Hole-in-the-Rock colonizing party passed through in 1879 on its way to the San Juan River country. The large party, some of its members my own distant relatives, made the trip in six months, a trip they foolishly thought would last only six weeks.

Edna soon came to Escalante and met many of the town folk. Coming and going from trips, we spent a lot of time at cousin Mohr Christensen’s Moqui Motel. My clients met there and at the other rustic-looking motels in Escalante when coming on trips.

Edna loved Escalante Canyon and became intimately familiar with its features. We frequented Coyote Gulch more than any other canyon. It contains Jacob Hamblin and Coyote natural bridges and Jug Handle Arch. At its mouth and across the river, Stevens Arch looms high on the skyline. Negotiating this country often came hard. Going down Coyote Gulch on one trip, a giant part of the wall broke away and crashed into the creek bottom below, forming a natural dam. My old intrepid friend Vaughn Short, who helped me a lot through those years, aided me in fashioning a detour around the slide and I got our horses and mules around the long pool of water. Edna followed that trail on numerous occasions, as it led to Indian wall writings.

Also, we often visited the wondrous Broken Bow Arch in Willow Gulch, one of her favorites. Downstream, we’d hike and climb into the narrow confines of 40-mile Creek.

When I first went overland into Davis Gulch, Lloyd Gates drew me a crude map. With pencil in hand, he directed me to a point on a mesa where the stock trail quickly dropped into the canyon. Edna loved following old trails like that. She joined an April 1963 trip into Escalante Canyon and she followed it up with another in a different part of the canyon. She loved exploration. We chatted about Everett Reuss by the hours. Everett Ruess, the young, wandering poet, left several ‘Nemo’ in Davis Gulch, and his graffiti became a destination favorite because he vanished there in 1934. He left his traces in the ruins and writings on the walls and so the “Everett Ruess Natural Window” became a testament to his memory.

During the next couple years, she took a Green River trip through Desolation Canyon and a Cataract Canyon trip. Then she signed up for hiking trips into Escalante Canyon, The Standing Rocks, and the Kaiparowits Plateau.

We were fighting the progression of time and the rising of the dam waters. Soon, the waters covered the lower part of the Hole-in-the-Rock and the Register Rock where a few of my own kin scratched their names onto the walls. Prior to the inundation, Edna took careful note of the inscriptions.

Then the reservoir waters drowned out the enchanting Cathedral in the Desert. It devastated the beautiful Gregory Natural Bridge and destroyed thousands of ancient Indian ruins and sites. It killed beaver and many other animals; their carcasses found at the end of numerous canyons. This upset Edna very much.

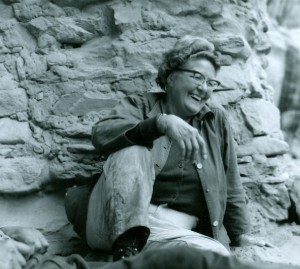

When I met her, Edna was a good looking and charming person of middle age, and from Hungarian stock. Her attractiveness came largely from her energy and her interest in searching the canyons. She relished history and archeology. And Edna loved Grand Gulch.

Once, in Grand Gulch, we got hit with a heavy rain and flood. Edna had gone a couple of days before and awaited our party downstream. Vaughn made his way down to her and walked her back to our camp. For the next three days we sat in an Indian dwelling watching the constant flooding. The floods kept coming and we drank the last of our libations. The fourth day we walked out of the canyon.

One day, down in Grand Gulch, while riding my hose and leading a couple of pack horses, I saw Edna sitting on the creek bank some distance below, intently looking up at the canyon wall. She hadn’t noticed me yet. I quietly pulled Knothead to a still, and watched her. “What is she looking at?” I thought. “A bird?” It seemed that she had gazed at the wall for many minutes. Curiously, I looked up on the same wall in the direction she was looking, but I didn’t discern what she aimed her eyes at. I urged my horse forward for a closer look.

On my dismounting, Edna noticed me and took her eyes from the wall. “What you lookin’ at Edna,” I inquired with much interest.

“I found another Kokopelli!”

She directed my eyes with her walking stick and I saw a delightful pictograph that I had never seen before. We happily discussed her great discovery for a little while and then, mounting knothead,, I headed down canyon to set up camp. Edna waited there for other party members to catch up so that they’d not miss her discovery. So, now, whenever I pass that same site, I always look up and wave at “Edna’s Kokopelli.”

She came to know most of the boatmen guides and wranglers who worked with me during the 1960s and 70s. Besides myself, there were river guides Jack Brennan, Harry Aleson, Brad Dimock, Cliff Rayle, Bob Shelton and Den Lehman. Among the wranglers and guides were Reeves Baker, Mac LeFevre, Bill Adams, Owen Severance, Vaughn Short, and Pete Steele. And, of course, our infamous pilot, Bill Wells, the Flying Bishop of Hanksville, must be included. We were all essentially her students. As an intrepid de facto guide, on meeting at the motels, Edna would often pull out some of her slides from her camper, set up her projector and show pictures of other trips she had taken to the guests. She helped greatly to entice the people to go on them and kept my business alive. On one occasion, she even came to Green River, where I lived in my small warehouse, and she helped me get my records up to date.

And she was a great companion on the trips. Though all of us had different occupations, we had great camaraderie among us all as we all pretty much shared the same interests and activities. When she wasn’t traveling with me, she made frequent trips with her friends: Sam Carter, Eunice Tjaden, Virginia Kavenaugh, Dorothy Mitchell, Delcie Vuncanan, Charles and Wilma Murray, Janet Tibbetts, Bea Rizzolo, Tad Nichols, and a host of others. In April of 1973, she backpacked alone into Grand Gulch and I carried some of her supplies and dropped off “food pack #1” to her. Then her husband Charles came down with my group and Edna rejoined us. On our way out of the canyon, I dropped off “food pack #2” to her. She and her friend Delcie Vuncannon were to explore the lower Grand Gulch. Shortly after that, the two backpacked into Horseshoe Canyon.

Not only did Edna and I share the love of the great outdoors, we had a great time sharing the canyon experiences. In just a few years, we took in numerous canyons and rivers. We took trips into Kanab Canyon, a weeklong Labyrinth Canyon river trip, and a number of repeated trips into various sections of the Escalante Canyon. We took a Peru trip to the Maya ruins at Cusco and Macho Picchu. After one trip, she informed me that she had sugar diabetes. She wrote me: “That probably explains why I seemed to be trying to drink the Coyote Gulch and the Escalante dry.” In the future she planned her diet more closely and she brought some of her own “water-packed food”—which the mules enjoyed packing.

We took varied wilderness trips to the Waterpocket Fold, Horseshoe Canyon, the San Juan River, Paria Canyon, The Big Bend country on the Rio Grande, Powell Plateau in Grand Canyon, Havasu Canyon, Desolation Canyon on the Green River, and the Hole-in-the-Rock. Then we took a backpacking trip, with inner tubes tied to our packs, through the Black Box of the San Rafael River. A later letter read, “I’m so grateful to have gotten into & through the San Rafael.” That was some kind of trip. Whenever I’m driving past the Swell, I always grin—and sometimes give a “yippee!” now that it’s in the past & I survived; a couple of times there, I wasn’t so sure I would.

In January 1970, she went with me to Mexico to run the Usamacinta River. And on that trip she fell at one of the Maya ruins and broke her arm. With the help of a local mortician, I put her arm in a cardboard splint and planned to send her out at the first opportunity, but she refused to leave the party. After the ten-day trip, she flew to Miami, where her arm was x-rayed and placed in a plaster cast. Her husband Charles wrote me that the arm was indeed broken but did not need to be reset.

When 1972 rolled around, we were all shocked at river guide Jack Brennan’s passing. And this was followed up with the bad news that Harry Aleson was seriously ill and had entered the hospital at Prescott, Arizona. I drove down to see him and Harry died soon after. Those were sad days for all of us, as we had developed such a tight bond with each other.

In February 1973, Edna dropped me a note that she heard that the Sierra Club was to take a trip into Grand Gulch in April. Edna wrote, “Ye Gods—poor Gulch will be worn out—It’s mine!”

By 1979 her health diminished. Sugar diabetes hampered her activities and it was more difficult for her to get around. From time to time she did get to drive about, but it was a growing problem. She had taken her last trip with me.

In February 1984, Edna entered the hospital for the removal of a colon tumor. She refused chemotherapy treatments and bemoaned the fact that she couldn’t take any more trips. While recuperating, she wrote: “It’s mighty hard to refrain from getting behind that wheel and rolling down the road on a sunny day.”

She wrote to me once, “When you’re looking at Broken Bow, think of me.” When I last visited it a couple or so years ago, I did think of her and her wonderful arch. She died about that same time, expressing to the end her great love for the canyons.

3 Responses

Stay in touch with the conversation, subscribe to the RSS feed for comments on this post.

Sweet story. Thanks for sharing it.

Woke up this morning with the words, “Edna Canyon” on my mind. When I searched the web, this wonderful article came up!!! What a great story about a truly interesting group of people. Thank you!!!

My husband and I sat out a similar flood in a ruin in Grand Gulch about 10 years ago. This flood was unanticipated (it was sunny and 85 degrees immediately beforehand, we have “before” photos to prove it) and absolutely devastating to the canyon trail, which disappeared under a house-sized Boulder that blocked the entire canyon so that we had to crawl over it on our hands and knees after the floodwaters went down. Hail and rocks cascaded down the canyon walls and pretty soon we were walking in brown water with a layer of ice cubes on top. If it weren’t for the Indian ruin we were forced to take shelter in, I would have rapidly become hypothermic and we would have had a real medical emergency. We were so scared and busy trying to figure out how to survive that we didn’t get any photos of this event after the first few minutes. Too bad! Let that be a lesson to you. Flash floods happen constantly in canyon country and they are all they are cracked up to be. Watch out!