I’ll tip my hat to the new constitution

“Won’t Get Fooled Again,” Pete Townshend, The Who

Take a bow for the new revolution

Smile and grin at the change all around

Pick up my guitar and play

Just like yesterday

Then I’ll get on my knees and pray

We don’t get fooled again

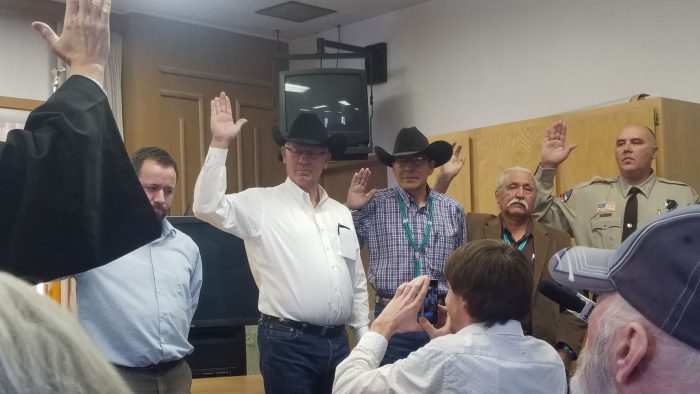

When Willie Grayeyes and Kenneth Maryboy took their oaths of office in January, San Juan County became the first in Utah to have a local governing majority of Native Americans and, importantly, one that comprised activists who have played a leading role in a bitter multiyear, multimillion dollar political campaign to create and now litigate Bears Ears National Monument.

Its “historic” status has survived a legal challenge that alleged Grayeyes was not a resident of Utah and therefore ineligible to hold public office in the state. In a controversial ruling on Jan. 29, 7th District Judge Don Torgerson cited, in part, the commissioner’s “rich cultural history” and his observance of “traditional cultural practices” in Navajo Mountain, Utah, community as forming the basis of residency.

Neither Grayeyes or Maryboy has publicly signaled an intent to curb their activism regarding expansion of tribal sovereignty beyond the Navajo reservation into Bears Ears country in order to represent the interests of conservative Navajos and ancestors of Mormon pioneers – a bloc of constituents that convincingly demonstrated in November’s election the county as a whole remains deeply red.

Democrat Jenny Wilson got only 31 percent of the vote countywide against Republican Mitt Romney in the race for U.S. Senate; Democrat and Navajo James Singer got only 27 percent against Republican incumbent John Curtis in the race for Congress; and Marsha Holland ran unaffiliated and got 33 percent against Republican Phil Lyman in a state House race that wasn’t even contested by Democrats. Likewise, Democrats could find no candidate to run against incumbent Republican District 1 Commissioner Bruce Adams.

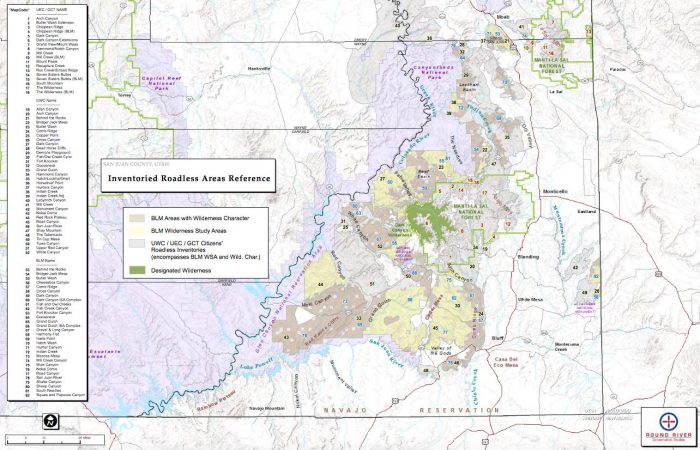

For Maryboy and his brother, Mark, the Bears Ears project is a passion that began in 2010 after former U.S. Sen. Bob Bennett (R-Utah) sought their help to resolve long-simmering land-use issues – a chance to right what they might believe are historical wrongs. Shortly after that they launched their own initiative with seed money from the David and Lucille Packard Foundation and technical assistance from Round River Conservation Studies, based in Salt Lake City. Grayeyes has been involved almost as long.

The effort morphed into Utah Diné Bikéyah and it took an assertive, high-profile lead: Leonard Lee, vice chairman of the group, remarked, “We don’t consider ourselves as stakeholders. … We’re the landlord.”

Here’s the $64,000 question: Will the policies of the new pro-Bears Ears county commission begin to align – to varying degrees – with the goals of a grand alliance whose members include the foundation established by multibillionaire Hansjorg Wyss ($2.2 billion, see sidebar), Utah Diné Bikéyah, Round River Conservation Studies, Friends of Cedar Mesa, the Conservation Lands Foundation, the Grand Canyon Trust, Southern Utah Wilderness Alliance, Earth Justice, The Wilderness Society, Natural Resources Defense Council, The Nature Conservancy, Packard Foundation ($7 billion), William and Flora Hewlett Foundation ($9.8 billion), Wilburforce Foundation ($115 million), Pew Charitable Trusts, Leonardo Di Caprio Foundation and some of the nation’s most prominent and politically aggressive outdoor recreation companies?

————The Players: Hansjorg Wyss————

The power of a cluster of rich environmental foundations – unaccountable to democratic institutions and each with varied and often competing goals – has contributed to the stalemate over land management in southeastern Utah. The Wyss Foundation, a project of Swiss multibillionaire Hansjorg Wyss, who lives on the eastern flank of the Tetons, just outside Jackson, Wyo., is an example.

His foundation contributes significant sums to environmental causes, including the pro-Bears Ears campaign in general and specifically $55,280 to Utah Diné Bikéyah in 2016. He’s quite generous, but critics have pounced on similar efforts as masking bad by doing good.

Wyss led Synthes, a multinational medical device manufacturer that specializes in medical implants and biomaterials, until he sold it in 2012 to Johnson & Johnson for an estimated $20 billion.

In 2009, Synthes faced 52 felony counts stemming from allegations that it illegally experimented on patients, three of whom died.

The alleged conduct occurred from 2001 to 2004, in which patients were injected with the company’s bone-cement product, Norian, despite the U.S. Food and Drug Administration’s refusal to approve the product. Four high-ranking executives pleaded guilty for the company’s crime of running unauthorized trials and promoting the product for unapproved uses, without conceding that they were involved in the crime. Wyss was never charged in connection with any crime.

(Editor: The Zephyr sought comment through the Wyss Foundation but did not receive a response.)

One tactic to attain strategic environmental goals has been Wyss’ use of the Western Values Project. Buried deep inside a multimillion-dollar “charity” called the New Venture Fund, WVP has become a “go-to” source whose reports are accepted at face value by mainstream media and spread all over Creation via the internet.

In a letter dated Feb. 26, 2018, WVP asked the Department of Interior inspector general to investigate possible conflicts of interest involved in shrinking Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument. The nonprofit alleged boundaries were redrawn by Secretary Ryan Zinke and Interior to personally benefit former state Rep. Mike Noel (R-Kanab,Utah). Reports based upon WVP’s complaint were published extensively.

The IG investigated and found no wrongdoing. “In a phone interview … Noel blamed the Western Values Project, a liberal advocacy group, for spurring the inquiry by first questioning why his property was excluded from the monument,” according to the Washington Post.

WVP has no office mailing address, instead mail is received at 704C East 13th Street, Suite 568, Whitefish, MT 59937. That address is the Whitefish UPS Store. “Suite 568” is actually a $150-per-year private mail box, snugged next to a sales placard touting a “street address, not a P.O. box number,” according to Flathead (Mont.) Beacon columnist Dave Skinner.

“Western Values Project brings transparency to the public lands debate,” according to its website. “Western Values Project is a project of New Venture Fund, a 501(c)(3) public charity fiscal sponsor that provides administrative support to hosted projects — an umbrella organization that provides administrative support to non-profit advocacy organizations.”

Skinner reported that he poked around the Internet for either corporate registration records or federal documentation granting WVP tax-exempt status but found nothing. In 2013, WVP’s first press release says that WVP “receives financial support from New Venture Fund.”

The Wyss Foundation gave New Venture Fund $4.2 million in 2016 and $4 million in 2015 ($3 million to The Nature Conservancy in 2016 and $500,000 to Grand Canyon Trust in 2015).

In addition to environmental causes, Wyss supports center-left political candidates and “community empowerment” organizations. Former Rep. Jim Matheson (D-Utah) received contributions from Wyss.

—————————————————————-

Grayeyes and Maryboy offer clues about where their loyalties might lie in documents obtained by the Zephyr. They’ve prepared four resolutions that reflect their long-time pro-monument activism: one rescinds all of the previous San Juan County resolutions in support of Trump’s monument; another directs Laws to conduct an inventory of all civil litigation in which the county is a party; and a third directs that some regular meetings be held in the southern part of the county, including parts of the sovereign Navajo Nation (“The County Administrator shall immediately contact the chapter managers of the Navajo Mountain, Oljato, Mexican Water and Aneth chapters, as well as the Town of Bluff”).

A fourth resolution directs county attorney Kendall Laws to withdraw the county from the big monument lawsuit – Utah Dine Bikeyah et al. v. Donald Trump, et al. – and sever ties with Mountain States Legal Foundation, which assisted the county in litigation. According to its website is “dedicated to individual liberty, the right to own and use property, limited and ethical government, and the free enterprise system that defends constitutional liberties and the rule of law.’

If the resolutions are introduced and OK’d by Maryboy and Grayeyes, they will have voted to terminate the county’s lawsuit against the nonprofit, Utah Diné Bikéyah, that they had recently run as board members. Both resigned their positions on the board of UDB just prior to assuming their positions on the County Commission.

——The Players: Gavin Noyes—-

Gavin Noyes, who has been affiliated with Utah Diné Bikéyah since its inception, was quoted by Taylor Stevens of the Salt Lake Tribune, as saying “You look at the county land plan that (the old Commission) just passed and it’s all about mining and grazing and, you know, multiple use,” Noyes said. “And I think that the Native American view of the land is really different than that. It’s all about sustainably interacting with the land. Using it, but in a way that’s pretty light. Light on the landscape. It’s not about extraction.”

In fact, most of the land inside the county is owned and managed by state, federal or tribal governments, much of it under multiple-use legal mandates. Many of the profitable mineral extraction opportunities and jobs they produce lie within the Aneth extension of the Navajo Nation, over which the county has no control. Much of what lies below is pumped up by Navajos themselves (many of whom work for the Navajo-owned Navajo Nation Oil and Gas Company) then delivered to refineries via the Navajo-owned Running Horse Pipeline where it’s transformed into gasoline and pumped into Navajo-owned cars and trucks at Navajo-owned Navajo Petroleum gas stations.

Noyes’ comments – “Using it, but in a way that’s pretty light” – reflect Utah Diné Bikéyah’s current ideas on land use and economic development in one of the country’s poorest regions at least as much as they do about contemporary Native Americans’ complex connection to the natural world.

The comments are consistent with Kenneth Maryboy’s long-term support of tourism and UDB’s for-profit recreation-oriented benefactors helping to fund the campaign to restore Bears Ears National Monument to its former size. But they don’t necessarily mirror the views of most Navajos or Native Americans in general.

Maryboy was tapped as a lobbyist a couple of years ago to drum up support for what would’ve been a massive tourist development called the Grand Canyon Escalade at the confluence of the Colorado and Little Colorado rivers, which many Navajos consider sacred. The project envisioned an aerial tram delivering as many as 10,000 people every day to the floor of the Grand Canyon, a riverwalk, amphitheater, food pavilion, Navajoland Discovery Center, hotels and recreational vehicle park. Delegates to the Navajo Nation Council voted it down.

Marley Shebala, a reporter for the Gallup (N.M.) Independent who writes out of Window Rock, Ariz., describes a contentious meeting on Nov. 14, 2016, of the Navajo Council’s Naa’bik’iyati’ Committee. It provides a glimpse of Maryboy’s priorities and political tactics.

Maryboy said that the Northern Navajo Medicine Men’s Association had appointed him chairman and that the group supported the Escalade. Law and Order Committee member Council Delegate Otto Tso challenged him, saying that, in fact, the Northern Navajo Medicine Men’s Association opposed the development, as did Diné Medicine Men’s Association, the Diné Hathali Association and the Naa’bik’iyati’ Committee’s Sacred Sites Subcommittee.

Tso told the Escalade developers, “If you want to build it, build it in your backyard. We don’t have to develop our sacred areas.”

Maryboy did not respond.

President Obama’s larger version of Bears Ears National Monument would enhance prosperity for southeastern Utah, according to comments Noyes submitted to the Bureau of Land Management (June 2018 press release) regarding its management plan for President Trump’s smaller version of Bears Ears National Monument. Currently, Native American culture is insufficiently “monetized.”

Noyes suggested BLM consider what seems to be some sort of government jobs program.

“The BLM is a significant employer in San Juan County. UDB would like to see a process of community engagement to determine whether the Bears Ears visitor center should be located in Bluff, White Mesa, Mexican Hat, Blanding or other community. We also recommend that a great majority of new jobs that may arise if funding is adequately increased go to citizens who have the Native American cultural background to engage tourists and carry out law enforcement, monitoring, restoration, planning, as well as the highest level administrative positions.”

In a region with some of the nation’s highest unemployment rates regardless of race, Noyes prioritizes just one.

——————————————–

ABOUT 30 OR SO PEOPLE SHOWED UP on Dec. 4 at the University of Utah’s student union theater to mark the anniversary of President Donald Trump’s proclamation that shrunk Bears Ears National Monument by 85 percent. Several documentaries produced by Native Americans were shown and filmmakers discussed their work.

It offered a candid glimpse inside the campaign to create and litigate Bears Ears National Monument and the “no retreat, no surrender” ideological perspective of its Native American and allied leaders. Utah Diné Bikéyah hosted the event.

Moderator Angelo Baca, a staff member of UDB and graduate student at New York University, said the date is an important benchmark in the fight to create and now reclaim President Obama’s version of Bears Ears National Monument.

Many stayed to the end for a freewheeling question and answer session with activists who discussed among other things their political strategy to “undermine the Trump administration,” in the words of panelist Keala Carter, a public lands specialist with Bears Ears Inter-Tribal Coalition, and “re-indigenize” the region, according to Honor Keeler, assistant director of UDB.

There was talk of healing – at least among tribes and clans. An inspirational video, apparently funded with help from Outside magazine, showed members of several tribes that historically have not exactly been on cordial terms coming together for unity moments on a run across the high desert to Bears Ears. UDB’s schwag is even engraved “Bears Ears is Healing.”

Sheer vitriol, however, seems more the norm when dealing with anti-monument political opponents. You need revolution before healing, said Carter. Baca echoed that sentiment toward the end of a recent movie produced by KUED in Salt Lake City.

In a Facebook post dated Feb. 28, 2017, a commenter identified as Kenneth Maryboy referred to fellow tribal members who are political opponents as “tame Indians.” Much of the venom has been directed at anti-monument Democrat Rebecca Benally, who lost a bid for re-election as San Juan County commissioner to Maryboy in November.

Virgil Johnson, chairman of the Confederated Tribes of the Goshute and president of the Utah Tribal Leaders Association, referred to Benally as a “token” Navajo at a Jan. 23, 2018, public forum sponsored by the environmental group Utah Valley Earth Forum in Orem, Utah. He repeated a line of personal attack directed at Benally by Shawn Chapoose, co-chair of the Bears Ears Inter-Tribal Coalition and member of the Ute Indian Tribe Business Committee, at a congressional hearing in Washington, D.C., several weeks earlier.

On Jan. 6, 2018, The Salt Lake Tribune published an op-ed by Garon Coriz, a Santo Domingo (N.M) Pueblo and physician living in Richfield, Utah, with a headline likely written by a Tribune editor that referred to anti-monument Navajos, including Benally, as “window dressing” in service of Trump’s agenda. “Ultimately, Benally and her clique are the hammer and chisel in the state’s efforts to chip away at tribal sovereignty. … In Indian Country, with the history of individual tribal members sometimes betraying their tribes for a handout or payoff, she has become a pariah.” Coriz resurrected “Uncle Tom.” Among African Americans, there’s probably no insult more inflammatory.

Grayeyes – a Democrat and former chair of Utah Diné Bikéyah, esteemed among the tribal activists in attendance at the university event, an Elder projecting a sense that he would fight for what he believes – talked in general terms about how he has been the target of shady political maneuvers. He said, perhaps prophetically, “they” have plans for him.

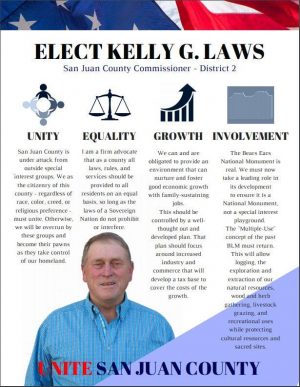

On Dec. 28, Kelly Laws, his Republican opponent in the November election filed a complaint against him in San Juan County 7th District Court. His team of attorneys is led by Peter Stirba, who represented former San Juan County commissioner and now state House representative for District 73, Phil Lyman, in connection with federal charges stemming from a 2014 protest ride on ATVs up Recapture Canyon east of Blanding. ATV access through the canyon had been closed by the Bureau of Land Management. District 73 includes San Juan County. Pamela Beatse and Mathew Strout are also part of Stirba’s team.

During the swearing-in ceremony on Jan. 7, Grayeyes was served legal papers challenging his Utah residency.

The judge in the case, Don Torgerson, a former public defender for San Juan, Carbon, Emery and Grand Counties who was appointed to the job by Gov. Gary Herbert last summer, ordered Grayeyes to testify at a Jan. 22 hearing and produce extensive documentation related to the complaint: his federal, Utah and Arizona tax returns for the past four years, copy of title and registration for vehicle(s) he’s owned for the past five years, records related to property ownership in Utah, Arizona and on the Navajo Nation, copy of a driver’s license and any other form of identification.

Grayeyes was kicked off the ballot in May after the San Juan County clerk determined he did not actually live in Utah. Grayeyes sued the county, his political opponents, and Utah Lt. Gov. Spencer J. Cox demanding to be put back on the ballot.

A federal judge ruled in early August that San Juan County officials improperly invalidated Grayeyes’ candidacy. His voting rights were restored and name returned to the ballot.

Questions related to Grayeyes’ residency, however, were never resolved.

Grayeyes’ team of lawyers – Steven Boos, Eric Swenson, David Irvine and Alan Smith – argued in a one-day bench trial that convened on Jan. 18 that Grayeyes could not have lost his principal place of residence at Navajo Mountain, Utah, unless he moved to Arizona and established a new principal place in a “fixed habitation” in a “single location” to which he always had the “intention of returning.” They believed that Laws’ complaint offered no proof – clear, convincing, or otherwise – that this move was made.

In making their case that Grayeyes’ principal place of residence is Navajo Mountain, they mention he went to school in that community and that he has a blood sister and a nephew who lives nearby. Sometimes he lives with them.

“Although Native Americans technically cannot ‘own’ land on a reservation, within the more limited sense of natural custom and related traditions, it can be said that Mr. Grayeyes is ‘heir’ to real property at Navajo Mountain, property which was left to him by more family members, his mother and an aunt,” Grayeyes’ response says.

The real property, in Grayeyes’s case, is much more than mere land, according to Grayeyes’ response to the complaint. It is his inheritance, a birthright from his local clan, and the place where, at birth, that family buried his umbilical cord, a sacred ceremonial space that signifies home and fixed habitation.

Grayeyes runs cattle at his homestead on Navajo Mountain, and, in Navajo tradition, the location of cattle is an important signifier of where one enjoys permanent residency.

Grayeyes admitted that he has an Arizona driver’s license and does not have a Utah driver’s license. But he argued that it’s not required for residency for election law purposes. Members of the Navajo Nation may vote by presenting any number of documents –not just a driver’s license – that establishes residency on the Navajo reservation.

Torgerson tossed Laws’ complaint. “He (Grayeyes) is connected to San Juan County as deeply as any resident of the County. In practice, he has always participated in the voting process in San Juan County. And his rich cultural history adds to his connection – he has always returned to the area and will always intend to return to the area when he has travelled away,” Torgerson said in his ruling.

In a particularly broad interpretation of statute, Torgerson ruled that a “particular home” is not required for a person to have a principal place of residence.

“As long as the location where the person resides is entirely within a voting precinct, the Court believes the ‘single location where a person’s habitation is fixed’ could mean a larger geographical area and include various places, particularly for someone like Mr. Grayeyes who observes traditional cultural practices. He may stay on Paiute Mesa under a shade hut during the summer. Or at his daughter’s cabin. Or at his sister’s house in Navajo Mountain. As long as those all fall within a single voting precinct, that geographical area is sufficient to be a principal place of residence.”

Torgerson ruled that Laws waited “too long” to bring his election challenge even though it was filed within the 40-day limit cited by relevant election law.

The judge’s decision can be appealed to a higher court. But even if an appellate court rules in Laws’ favor, a vacancy in the contested office would be declared. Utah election code provides that this vacancy would be filled by a member of the Democratic Party, whose sentiments likely would align with the newly elected pro-Bears Ears commission.

THE UNITED STATES (IN THE FORM OF THE FEDERAL GOVERNMENT) has flexed without much restraint its white might over Native Americans’ tribal affairs and culture, wildlife and natural resources, even existence from even before its founding.

It was based on what nowadays is considered morally dodgy rationalizations – Manifest Destiny, “The White Man’s Burden,” stuff like that. In legal parlance, they were de recto rationalizations and only recently legitimately challengeable. The status of Andrew Jackson, “hero” of the Battle of New Orleans, has receded because of heightened awareness of his role in the genocidal Trail of Tears, but polls indicate most Americans still believe Christopher Columbus did something worthy of a national celebration. His atrocities – so horrific they couldn’t be accurately depicted by contemporary media – are mostly overlooked.

The history of the country’s relationship with first Americans is littered with morally imperative (de recto) claims that morphed into acceptance because of on-the-ground realities (de facto) then cemented for posterity with legislative and judicial actions (de jure).*

Those same legal justifications were on full display in San Juan County as Judge Don Torgerson ruled on Jan. 29 that Willie Grayeyes is a resident of Utah and fully qualified to take a seat as county commissioner.

The complaint filed in state district court by Kelly Laws, who lost to Bears Ears National Monument activist Grayeyes, appears to have been based on a technical/legal read of the Utah code (de jure): He had no Utah driver’s license; he owned residential property in Arizona; would-be neighbors didn’t know him.

Grayeyes’ defense, however, seemed to have been relying, at least in part, on his cultural background as a Navajo and member of the Navajo Nation (de recto): birth place, cultural ceremonies, the burial of umbilical cords, and childhood reminiscences of “home,” etc.

Torgerson cited, in part, the new commissioner’s “rich cultural history” and his observance of “traditional cultural practices” in Navajo Mountain, Utah, community as forming the basis of residency.

The courtroom faceoff echoed the larger conflict over Bears Ears. As with Grayeyes’ residency question, tribal-affiliated Bears Ears supporters are invoking de recto sovereignty while monument critics are relying on de jure and de facto principles.

Grayeyes and the group he led as chair, Utah Diné Bikéyah, are armed with a fierce commitment to the propriety of their de recto claims to create and manage Bears Ears. It’s a legal strategy used successfully in recent years by a few tribes in North America, Australia and New Zealand.

They’re pushing legal and political boundaries – building the institutional and economic capacity to exercise self-rule even where de jure foundations may be ambiguous or even absent.

That is, many tribes – and tribal surrogates such as UDB – increasingly are embracing the Nike strategy of “just do it” because they believe it’s right. It worked for Mormon pioneers as they pushed through and settled lands held sacred by tribes for millennia. Facts on the ground then (de facto) trumped everything else. Why not revisit it?

Grayeyes and his activism are at the forefront of creating the facts on the ground that, in the Utah case at least, can give the Bears Ears Inter-Tribal Coalition’s claim of control over Bears Ears a firmer foundation.

Meanwhile, the tactic as deployed in San Juan County is creating a backlash that might substantially undermine any newfound gains. The backlash during the 1800’s was vicious. I doubt the outcome of the Laws/Grayeyes skirmish and the brouhaha over Bears Ears will be as bloody, but residents of San Juan County are in for a long ride.

* Sources of tribal sovereignty – de recto, de facto and de jure – are discussed at length in “Myths and Realities of Tribal Sovereignty: The Law and Economics of Indian Self Rule” by Joseph P. Kalt and Joseph William Singer of Harvard University, 2004.

Note: this article has been updated to reflect that both Kenneth Maryboy and Willie Grayeyes resigned from the board of Utah Dine Bikeyah before assuming public office. This was a serious oversight and the Zephyr deeply regrets its error.

Bill Keshlear is a frequent contributor to the Zephyr. He has been an editor at the Fort Worth Star-Telegram, San Diego Union-Tribune and The Salt Lake Tribune. He was communication director for the Utah Democratic Party during the 2007-2008 election cycle.

To comment, scroll to the bottom of the page.

Don’t forget the Zephyr ads! All links are hot!