The following excerpt is from the book: CANYON COUNTRY EXPLORATIONS & RIVER LORE: The Remarkable Resilient Life of Kenny Ross, by Gene M. Stevenson. The book was written about Kenny Ross, one of the forgotten personalities on the Colorado Plateau whose major influence on river running in the Southwest had been previously overlooked.

EXPLORERS CAMP PROGRAM FOR 1949

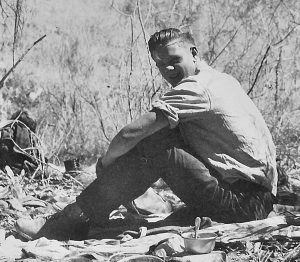

The summer of 1949 marked the sixth field season of the Explorers Camp for teenage boys. Ansel Hall was still advertised as the General Director, and Kenneth I. Ross was the Camp Field Director. However, almost all the correspondence, brochures, itineraries and activities were now under the control of Kenny and by the time the summer camp rolled around, it was called the “Southwest Exploration Field Program” and precise dates were delineated for the camp activities. The camp was scheduled to last nine weeks, from June 21 to August 22.

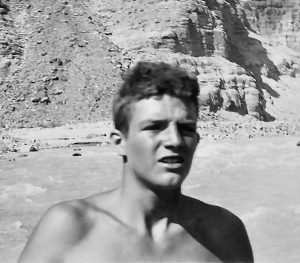

However, Mother Nature and a series of cancellations drastically altered the plans and itineraries for that year’s Explorers Camp. The winter of 1948-49 was an exceptionally big snow year which caused immediate problems for their orientation period in June; and both camp councilors dropped out at the last minute and could not make it to camp. Ansel and Kenny had to make changes “on the fly.” However, Kenny was particularly happy to see Jon Lindbergh and Bill Dickinson’s return as they became his main camp assistants, and the post-camp Cataract Canyon river trip with these two was still scheduled, even if it was just the three of them, so all was not lost.

THE HIKE BEFORE CATARACT TRIP

The group of Explorers led by Kenny Ross departed for Elk Ridge on Thursday, August 4 and then hiked into Woodenshoe Canyon and down Dark Canyon to its mouth at the Colorado River. By now, Kenny knew this trek fairly well, having been there twice before – in 1946 and 1947. On this particular trek, Jon Lindbergh wandered up the river bank a mile or so to look over the rapids in anticipation of the upcoming river trip. Kenny recalled that Jon quietly came up behind Dick Griffith and said “Hi there!” and nearly scared him to death. According to Kenny, Dick Griffith had no idea any human being was within a hundred miles of him. Imagine his surprise? Kenny’s written Explorers Camp notes only state the following when Jon came upon Dick Griffith:

He ran into a lone boatman, Dick Griffith of Fort Collins, Colorado, who, to our knowledge is the only other person to run Cataract this year. Griffith had traveled down the river alone from Greenriver, Utah and seemed grateful for the opportunity to eat supper with us and to sleep near other humans. He told us of his adventures in the rapids above and expressed himself in no uncertain terms concerning the foolishness of anyone who would tackle Cataract without companions. His boat was a 15-foot rubber landing craft, similar to our 12-ft boat and he ran it with oars by the method worked out during the 1890s by Nathan Galloway, of Richfield, Utah.

Following breakfast next morning, Griffith, with Jon Lindbergh as passenger, ran Dark Canyon Rapid, while the Explorers looked on and took pictures. He chose a course near the left shore, where the water is so shallow that there was just enough to grease the rocks so the boat could slide over and around them. Got thru okay but Jon and the other Explorers were a little disgusted because Kenny had always taught them to run a ‘clean’ boat and that means to avoid bumbling over rocks. However, Griffith knows his business and had good reason to fear the high waves and grinding current of the channel near the far right shore—where most of the river poured thru with demonic power.

The Explorers group took a couple of days hiking out of Dark Canyon back to the vehicles and then traveled back to Gold King base camp arriving on Friday, August 19. The boys took a few days to get the camp in order, celebrated with a big campfire and barbeque at that year’s camporee and camp was officially over by Tuesday, August 23.

Once again, the adult camp councilmen had cancelled earlier that summer in working at the Explorers Camp and in going down Cataract Canyon in August with Kenny, as had Ansel Hall and Charles Lindbergh. Therefore, the scheduled two-boat trip was reduced to just one boat with Kenny, Jon Lindbergh and Bill Dickinson. Kenny had been eying Cataract Canyon for four years now and Jon nearly as long and had at least taken a “thrill ride” down part of Dark Canyon Rapid. These three had been talking about a Cataract trip since the previous year and there was no turning back, even if it was with one boat – the 12-1/2 ft long 7-man LCR.

They were fully aware of the remoteness and dangerous rapids. Kenny had studied the canyon and what little was known from written reports and handed down stories. Kenny had made hand-written notes from Frederick S. Dellenbaugh’s account from his 1871 trip with John Wesley Powell and Robert Brewster Stanton’s count of seventy-five rapids in Cataract Canyon. He read about the 1891 “capsize disaster” in Rapid #15 on the Best Expedition and the Kolb Brothers and the Stone Expeditions run in 1909. He knew that Norm Nevill’s group in 1940 had problems in a stretch of particularly big rapids that Bert Loper in 1907 called the “Big Drops.” Apparently, Del Reed pinned one of Norm’s boats (the Joan) in Big Drop #3 in July, 1940 with trip passenger Barry Goldwater on shore taking pictures and in the process of retrieving it, the boat capsized and all the gear got soaked. And Kenny was very aware of the treacherous notoriety of Cataract Canyon which had become known as the “Graveyard of the Colorado” ascribed to the Kolb Brothers following their river trips in 1911-12 down this stretch of the Colorado River.

The 1949 Explorers Camp had been exciting and certainly different with all the unscheduled events scattered throughout the summer. The biggest point was that the other camp leaders had bailed for various reasons and the entire season’s activities had fallen onto Kenny’s shoulders. But it was worth it, because now he was about to embark on a trip that had escaped his fancy since 1946 – he was finally going to run the rapids of Cataract Canyon!

CATARACT CANYON

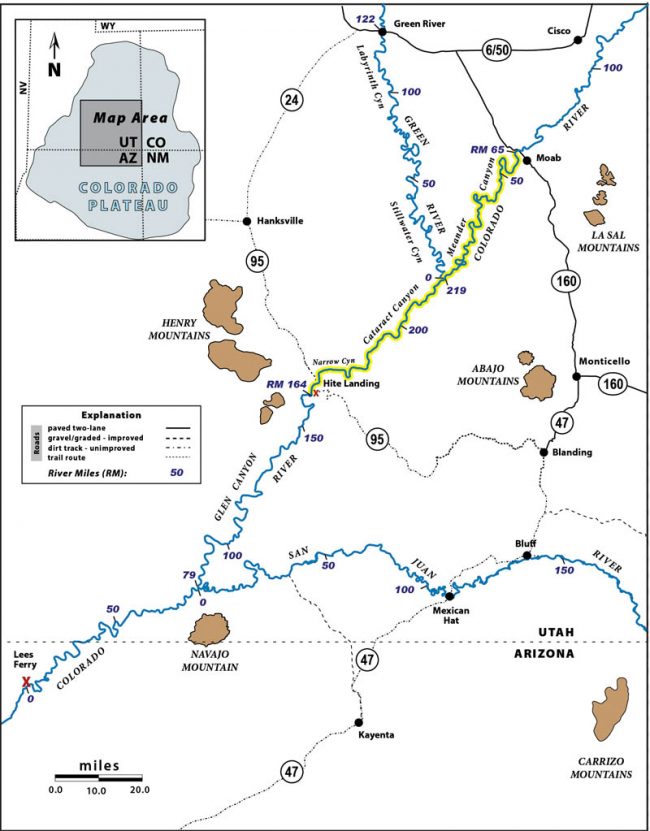

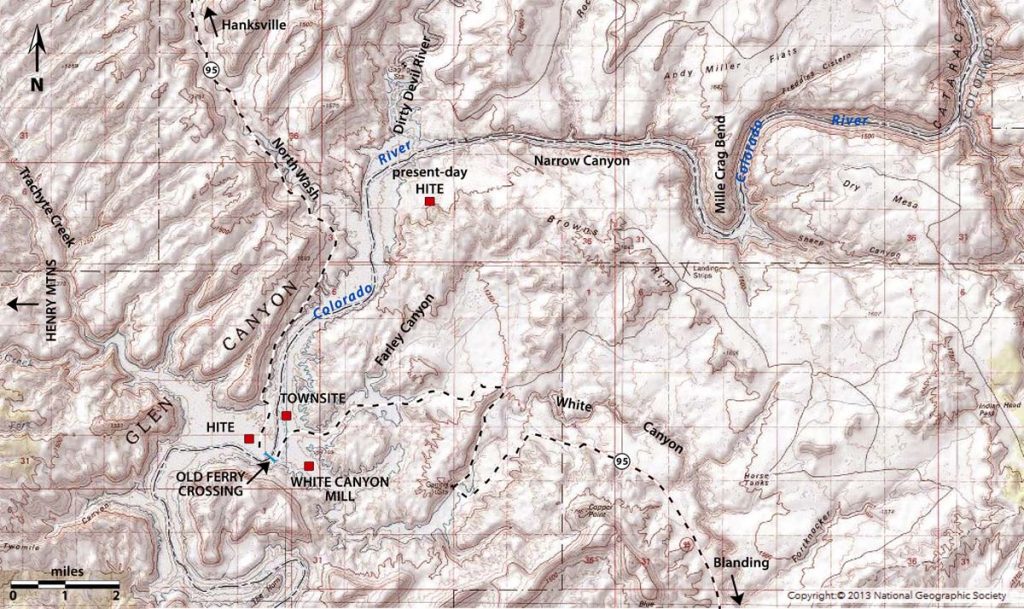

The rivers that flow through the canyon country of the Colorado Plateau are typically subdivided into subsections of the numerous canyons cut by each rivers course. Above Cataract Canyon, the Colorado (Grand) River cuts a canyon named Meander Canyon which extends sixty-two miles from The Portal west of Moab to the confluence with the Green River. This section has a very low gradient of less than one foot per mile with virtually nothing more than riffles and many sand bars and islands to dodge. The Green River below the town of Green River, Utah is divided into two placid low gradient anastomosing sections (Labyrinth and Stillwater canyons) for a distance of one hundred-twenty two river miles that averaged less than two feet per mile down to the confluence.

Cataract Canyon is that stretch of the Colorado River that extends from the confluence of the Green and Grand (Colorado) Rivers as the river doubles in size and flows generally in a southwesterly course down to Sheep Canyon Rapid in Mille Crag Bend – a distance of slightly less than forty river miles and drops nearly four hundred feet through some of the biggest rapids in North America. Below Mille Crag the Colorado flows westerly through a short seven and a half mile long section called Narrow Canyon down to the mouth of the Dirty Devil River that enters from the north side. Prior to the construction of Glen Canyon Dam and the subsequent inundation of Powell reservoir, from the Dirty Devil to Lees Ferry, a distance of almost one hundred-seventy two river miles the Colorado River flows through the serene low gradient Glen Canyon.

Present day access to Cataract Canyon by boat requires rowing or motoring down forty-eight river miles if launched from the Potash boat ramp on the Colorado River side, or fifty-three river miles if launched from the boat ramp at Mineral Bottom. But on Kenny’s first trip they launched just below the bridge crossing the Colorado River in Moab – a distance of sixty-five miles of flat water before they reached the confluence with the Green River. Then it’s still another four miles from the confluence to Rapid #1 (also known as “Brown Betty” Rapid). River elevation at the head of Rapid #1 is 3820 ft and the elevation of the last rapid in Mille Crag Bend (pre-Powell reservoir) at Sheep Canyon is 3460 ft for a total elevation difference of 360 ft over the 35.8 river miles or an average gradient of 10.06 feet per mile (fpm).

But Cataract’s gradient has anything but a steady drop of ten feet per mile; it drops in a series of stair-steps with the biggest occurring at Mile-Long Rapids (Rapids #13 – #20) where the river drops forty-nine feet in less than two miles and the biggest drops occur a few miles below the bottom of Mile-Long Rapids at the “Big Drops” (Rapids #21-#22-#23) where the river plunges thirty-two feet in less than one mile! Prior to the inundation of Powell reservoir, the single largest rapid was at Dark Canyon where the river dropped twenty feet across the length of the rapid that was approximately a quarter-mile long. Nearly all the major rapids were due to substantial side canyon flash floods that brought large volumes of boulder-fan debris that caused constriction of the main stem.

On his first trip in 1869, Major John Wesley Powell felt that the sixty-plus rapids over less than forty river miles were of such size and complexity that they deserved a more descriptive name than referring to that section as containing “rapids” and named it Cataract Canyon. Cataract Canyon had also gained the name “the Graveyard of the Colorado” due to an unknown number of river runners, trappers and prospectors who entered the canyon only to never be seen or heard from again. Not all these folks necessarily perished in the river however; many were suspected to have hiked out and probably died of thirst, regardless of having climbed out to the west or east rims. This situation still exists today as some of the most rugged and remote country in the conterminous U.S.A. awaits the unwary visitor. Whether traveling overland or by river one must know they are basically on their own and should enter this country prepared for emergencies.

So, just how many rapids or drops exists in this thirty-six mile stretch? What constitutes a rapid being called a rapid in the first place? One man’s rapid could be another man’s riffle, or even not mentioned. These questions were on all the early boaters’ minds and the numbers varied from forty to seventy. The presence of a solitary rapid obviously depended on the volume of water; the lower the river, the higher the number. On Kenny Ross’s trip in 1949 they documented sixty-seven rapids between Spanish Bottom to Mille Crag Bend and the detailed river log was one of the first, if not the first, to keep a reasonably accurate number of rapids. The river volume on the Ross trip through Cataract was estimated to have been running at approximately 7500 cfs, which, by modern day standards would be a relatively modest water level.

CATARACT CANYON RIVER TRIP LOG:

August 23 to September 8, 1949

The log began on the last day of Explorers Camp season, Tuesday, August 23, 1949 with a meticulous listing of the details of the boat, gear and weight. River Miles (RM) follow the 1921 USGS measurements upstream from Lees Ferry to the confluence of the Green and Colorado Rivers. All quotes are from the Ross River Journal, as follows:

One boat – Neoprene Land Boat – 7-man – 12 ft – 5 ft. beam – 11 air compartments including air-mattress bottom. Equipped with heavy canvas deck – forward two-thirds. Two forward compartments lined with double nylon tarps for storage – tarps @ 7-11-ft for top waterproofing, under canvas decking. Four spare paddles. Three persons.

Weight of supplies and equipment – including 10 gals water… 310 lbs at start

Weight of passengers (combined)……………………………………… 460 lbs

Weight of boat empty ………………………………………………….. 325 lbs

=1,095 lbs

Leader – Kenneth Irving Ross – 41 – 148 lbs; Mancos, Colorado Director, Explorers Camp

Jon Morrow Lindbergh – 17 – 137 lbs; Darien, Connecticut, Mbr ” “

William R. Dickinson – 18 – 175 lbs; Santa Barbara, California, Mbr ” “

From August 23 to August 27 the three cleaned up and shut down Gold King camp for the winter and moved mattresses, beds, surplus canned foods and odds and ends by truck to the Mesa Verde Company storage locker. By Saturday afternoon Kenny had sorted and packed all the food for the river trip. Jon and Kenny left Mancos in the Dodge Carryall, loaded with the boat and all the supplies, but had a flat tire on the Dodge near Pleasant View. Fortunately, Bill showed up in his car in time to help. They all made it to Monticello, Utah before midnight and camped. The following day they left the boat and supplies at a gas station in Blanding and shuttled both cars to Hite Ferry, by way of the improved gravel road to Natural Bridges National Monument. The road past Natural Bridges was an unimproved rough two-track and it took twelve and a half hours to drive the 175 miles. They left the Dodge at the White Canyon uranium mill and returned to Blanding in Bill’s car. They arrived too late to find a restaurant or “tourist court” open and ended up sleeping on the side of the road. Some things just never change in Blanding.

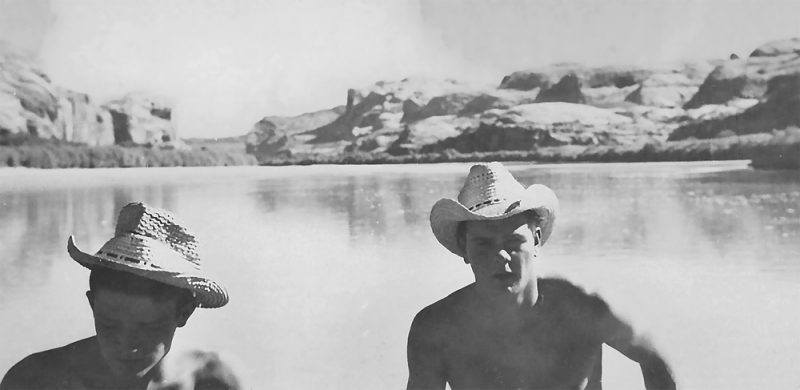

The next morning they loaded up their boat (the La Cucaracha) and gear and drove to Moab. They arranged to leave Bill’s car with Edith Bish Taylor and unloaded the boat, equipment and food only a quarter mile below the highway bridge and proceeded to inflate the boat. By launching from here, they had close to sixty-five river miles of very slow moving water to negotiate before they reached the first rapids in Cataract Canyon. They launched in late afternoon on Monday, August 29 and camped their first night on river right just past the Portal.

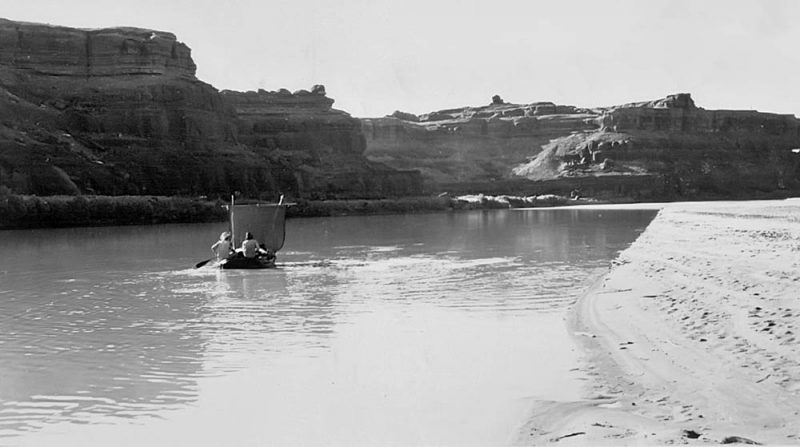

They made the long slow float to the head of Rapid #1 by the afternoon of Friday, September 2. The four-day sluggish float was noted by their encountering torrents of mosquitoes any time they attempted landing along the river banks and they decided to camp on sand bars in mid-river (a trick we have all learned who have experienced low water on Cataract trips). They also rigged up a crude sail with a nylon tarp to catch downstream winds, swam, and fished their way down to the confluence where they unloaded the boat and repacked, getting ready for the rapids. They ran Rapid #1 and #2 and accurately referenced their location as RM 212. They camped above Rapid #3

On Saturday, September 3 they ran Rapids #3 and #4, but stopped to scout or “conn” [slang for reconnoiter] Rapid #5 with a noted “WOW!” [Author’s note: Kenny preferred the two-man stern paddling technique, rather than rowing, but they were certainly “facing the danger.”]

They conned #5 and made mention that the Kolbs and others had described it as bad. A lengthy description followed, as Kenny and Bill were paddlemates and ran the “slick” water tongue between the top rocks just right but got shoved to the left into a big hole which knocked Kenny out of the boat briefly. Both Kenny and Bill lost their paddles but Kenny lost his hat. Luckily, they had spare paddles (no hat) and landed on river right to bail the boat and prepare for the next rapids. They conned Rapids #6 and #7 together and had perfect runs. They made note that Rapid #8 was RM 209 “at a point where the river has cut one limb of a sharp anticline, with its axis to the east” and noted they were still in the anticline as they ran #9 and #10. Kenny stayed on shore and photographed Bill and Jon’s run through Rapid #10, or the true “Brown Betty” rapid where the boat carrying that name in the Brown-Stanton expedition of 1889 was broken-up and lost.

Kenny and the boys ran Rapids #11, #12 and #13 and noted that Rapid #14 was RM 205 and they thought that they were at the beginning of what Stanton called Hell’s Half Mile. Rapid #16 was noted as the “wildest looking we’ve seen yet”. They conned the rapid and Kenny stayed on the left bank and photographed Jon and Bill’s run through the rapid. They ran and conned the next series of rapids, with exhilarating runs through #20 and #22 and made camp on the left bank after having run twenty rapids that day by their count and without lining a single rapid. They all agreed that day had given each of them sheer adventure and the most thrills of their lives. They were most proud of their packing method as their entire gear was perfectly dry.

Sunday, September 4 began a bit later and they all felt stiff from the previous day’s hard work. They successfully ran Rapid #23 at RM 203 by their count.

We thought that this was the most nearly flawless maneuvering we had done yet. In high water one might avoid this rough part of the rapid by passing to the left of an island bar in the river.

Their accounts provided the necessary comments regarding the island in the middle such that it was possible to correlate to modern logs and numbering systems and deduce that they ran Rapid #20 which has also been called “Ben Hurt” Rapid. They ran Rapid #24 (Big Drop 1) and Rapid #25 (Big Drop 2) successfully and their descriptions compare favorably to those of record today, and there was no question that their Rapid #26 was Big Drop 3.

“This was the most fantastic looking rapid we had yet seen.” Their mention that the top of the rapid was dammed by a mass of large boulders that create a lake effect was undeniably Big Drop 3. They conned from the left bank and while dashing back and forth several times they found an inscription on a nearby rock:

CAPSIZED No. 3

7-15-40

NEVILLS

They ran the “gut” by entering a narrow chute just left of center then down the left side before the boat spun right and then went through the tail waves.

Once they bailed the water out of the boat following their successful run of Big Drop #3 they ran Rapids #27 to #30 with no problems and noted that Rapid #30 was in three parts and the river bent sharply to the right. As noted in the comparison above, that would be the last rapid when Powell Reservoir was at full pool of 3700 ft and a camp site on river left named the Ten Cent Camp became popular to both river runners and lake boaters which created some heated discussion during full pool years. They stopped somewhere along this stretch for lunch. When they got underway again they didn’t stop to conn Rapid #31 that they correctly place at RM 200 and noted that “This is the longest continuous rapid we have run yet.” This was Imperial Canyon Rapid and has re-surfaced since the reservoir dropped in the early 1990s and reservoir level has never raised high enough to cover it again.

They ran Rapids #32 through Rapid #39 and made camp at the mouth of Gypsum Canyon (RM 196.5) around 5:00 PM:

This is an old stamping ground for all three of us. In early August of 1948 we had backpacked down Gypsum, via Beef Basin, with an Explorers Camp expedition, and camped right where we are now. One thing we know for sure and that is it’s better not to drink the water from Gypsum Creek. We had plenty of that last year.

We made 7 miles today and ran 17 rapids. We are 20 miles into Cataract Canyon – – with 21 yet to go. Our load was dry again tonight. We are all pretty bushed tonite and will sack in early.

Gypsum Canyon enters from the left and was named by J.F. Steward on Powell’s 1871 expedition. This was also the deepest part of Cataract Canyon. The bedded rocks at river level are gypsiferous strata in the Akah Stage of the Paradox Formation and the oldest strata cut by the Colorado River through Cataract Canyon. The Paradox evaporites are overlain by nearly a thousand feet of Honaker Trail gray limestones, then three hundred-sixty feet of red-brown slope-forming section of the Halgaito Shale and then another thousand feet of light-colored massive cliffs of the Cedar Mesa Sandstone (see Appendix II; Stratigraphic Column).

Kenny had lost his hat in Rapid #5 and had gotten way too much sun and was dehydrated. In fact, they were all dehydrated and sun-cooked and they elected to lay-over the next day, September 5, so that all three could recuperate. They erected a sunshade with nylon tarps “and spent the day loafing, eating, sleeping, reading, swimming….” Jon walked down the river and “conned a couple of rapids.” They got underway early on Tuesday, September 6 and ran Gypsum Rapid (Rapid #40) right down the center noting that this rapid had given them “the best sport so far with waves reaching 10 feet in height.”

They ran ten small rapids with minimal notes taken down to Clearwater Canyon (Rapid #51). Before they ran the rapid they walked up the narrow canyon and swam in a number of clear water pools similar to those in Dark Canyon. They returned to the boat and noted that the river was very narrow there and bent to the right; they ran the rapid left of center through “fairly high waves all the way through.” They noted that Rapid #53 was a rough one as it bent around a left curve and the roughest part was at the top. This might have been Bowdie Canyon Rapid at RM 190.5. They ran a number of small rapids and noted when they reached Rapid #59:

A vicious, rocky descent going around a left bend. Lindy had ridden thru this one with Dick Griffith, of Fort Collins, Colorado, in early August when the water was much higher. It took careful conning and precise handling for a safe run at the present level.

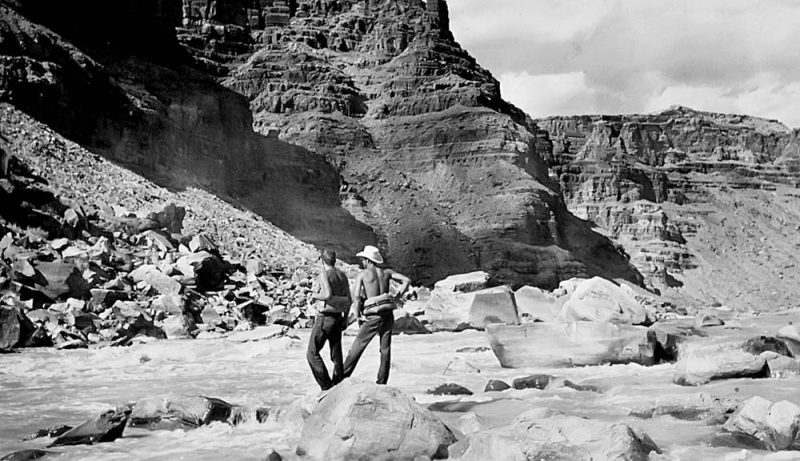

Two more small rapids were run and then they reached Dark Canyon Rapid or Rapid #62 by Kenny’s count with a major tributary canyon that entered from the left. Kenny was finally going to run this “bugger” of Cataract Canyon after first seeing it three years earlier.

This is a real rapid. It is about one-fourth mile long and rips viciously the whole distance. It has speed, rocks, high waves, trickiness, and terrifying power. It is formed by a dam of rock debris – – the “delta” of Dark Canyon, a deep, narrow gorge that spills into the river from the left. This thrust entirely across the Colorado, whose powerful stream is here narrowed into a space little more than 30 yards wide. The current has cut its deepest channel along the right bank and at the present water level most of the stream rages thru this with furiously compressed power. Near the center of the stream bed, extending from the bottom to more than half way to the top is an almost submerged island bar studded with protruding rocks. The deep channel runs to the right of this while to the left the water spreads too thinly over the rocks to permit passage of a boat.

From the upper point of the bar to the head of the rapid is a complicated arrangement of rocks that makes the task of jockeying for a favorable position in the swift current exceedingly difficult. The crest (the swiftest and highest standing part of the current) is broken up by these into several crests which, as they converge again into one, create high waves. The one crest is again broken by the tip of the island bar into two, the most powerful of which peels to the right into the main channel. Crossing and recrossing these crests had to be carefully calculated in advance because maneuvering here meant going broadside in the waves. The speed and power of each current had to be closely estimated because it would be very important to be on the correct side of the correct crest, at the right time and place. A mistake at any point in the upper fifty yards of the rapid might take us to the left of the bar where tremendous work would be required to get the boat back around into water that would float it. Over-compensating for this would take us too far to the right side of the main current where we would be thrown into the shore and ground to bits on the sharp rocks that line it.

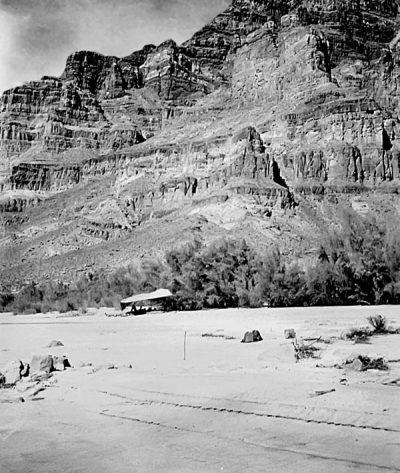

We landed at the head of Dark Canyon rapid a little after five o’clock. It was time to camp for the night but instead of unloading the boat we first walked down the left shore to discover whether we would be forced to run the right channel or if we could possibly bumble over the rocks on the left. We had occasionally speculated about this all the way down to Moab. If there was water enough to permit taking the latter course, we wondered which we would choose to do. Now there was no question. The water was too low to run any but the vicious main channel. The only alternative would be to portage boat and equipment to the foot of the rapid. Also, the question as to whether we would run it this evening or wait until morning was settled. The terrifying, deep-throated roar of the water and the sharper sound of boulders grating along the bottom resolved that. We looked at each other and grinned. Without yelling our throats above the bellowing of the rapid, each knew what was in the minds of the others; “Brotherrrrr, I’d lots rather listen to that thing tonight from the bottom than from its upper end.”

They were all familiar with the rapid from their previous visits after “hoofing” it down Dark Canyon, and it didn’t take long to conn the rapid and decide how they planned to run it. They made a successful run down the rapid and pulled in and landed on a nice sandy beach, right at the foot of the rapid and made camp exactly where they had camped only a month before. Kenny noted:

This spot has most certainly been used as a camping place by many river voyagers and it is the place where the second Powell expedition had lunch on September 28, 1871, after portaging their boats and equipment around the rapid. It is a real haven and from here, the sound of the rapid is just sweet music to a riverman.

Kenny mentioned that a permanent stream flowed out of Dark Canyon at this point and the water was drinkable and crystal clear. He also noted that just above the left bank of this little creek, right at the point where it emerges from the cliff-line, an almost obliterated inscription had been scratched on a flat rock surface that read “?? Turner–???7.” A closer inspection indicated that this was scratched over a still older inscription. A spring of clear, cold water flowed out of the cliff near its base fifty or sixty yards above the inscriptions. The spring was completely hidden by a thick screen of redbud trees. He found the high rock cairn, set in the open in front of the spring that was built by the first Explorers Camp expedition that conquered the 43-mile length of Dark Canyon afoot, in August of 1946. Kenny led this one, as well as subsequent expeditions in 1947 and 1949. Jon Lindbergh was on the last two and Bill Dickinson was a member of this year’s party. A glass jar within the cairn contained the names of all the members of these expeditions as well as names of at least two river parties.

On Wednesday, September 7, 1949 they were up early, packed the boat and took pictures of Dark Canyon Rapid. They proceeded downstream and encountered Rapid #67 (Sheep Canyon) which entered from river left at RM 177.0 around noon and passed Mille Crag Bend an hour later. Sheep Canyon rapid defined the termination of Cataract Canyon. Mille Crag (means a thousand crags) formed a sharp, rugged skyline and prompted Powell to give this section the name. The cragginess is due to a series of closely-spaced intersecting faults and joints that cross the river forming the rough landscape. They ran two small rapids in Narrow Canyon before they passed the Dirty Devil that entered from river right and they landed at the Hite Ferry at 6:00 PM. They derigged and stayed the night before they drove the Dodge truck the six and a half hours back to Blanding.

The last fifteen miles of slow paddling wasn’t discussed in the Ross journal, but Bill Dickinson provided an anecdote when I discussed this trip with him in June, 2015:

When we got within sight of Hite, some yo-yos had set up a target on a sandbar and were taking target practice by firing rifles upriver (nobody in that direction!). When bullets began plopping into the water near our boat, we began furiously slapping paddles on the water and yelling like banshees. The firing ceased and we floated home (profuse apologies from the riflemen but they really had no reason to suspect that anyone might be upriver from them back in those days). Ciao. WRD

Bill’s comments brought about a certain irony to their adventure. They had successfully run one of the most dangerous stretches of rapids in North America, solo, and then narrowly escaped getting shot by unwary rifle sportsmen.

Kenny showed his sincere love and friendship he had developed with Jon Lindbergh in a letter he sent to Col. Charles A. Lindbergh in March, 1950:

The Cataract Canyon trip which we made after Camp closed was all that we had anticipated. It is probable that we established some sort of record by being the first party to ever run this section, long known as the “graveyard of the Colorado,” with paddles. Jon has already regaled you with a first-hand account of our adventures so I will only add that much of the credit for the success of the trip belongs to him. Not many of the hand-full of really top-notch rivermen in the country excels Jon at white-water boating. He is a “natural” boatman. I introduced him to the “rogue” rivers of the Southwest and coached him at running rapids but he has “surpassed the Master.”

Kenny Ross’s first run through Cataract Canyon in late summer of 1949 would be followed by many more trips, but like so many things in life, the first time was impossible to duplicate! And the team of Kenny, Bill and Jon would never boat together again. Bill began college in 1950, but returned to boat with Kenny a few more times. The following year Jon joined Bill at Stanford University where their friendship continued to blossom. Both Bill and Jon continued to communicate with Kenny via letter writing for a few more years, but the young men were no longer the boys from the Explorers Camp.

THE DOCK MARSTON LETTERS

One last “key” point about a particular rapid in Cataract Canyon is noteworthy. Marjory Thorp was more than likely the passenger in Kenny’s boat when they ran the Big Drops in August, 1955 and when they ran Rapid #26 (Kenny’s count) she yelled that it was “like running through Satan’s gut!” Kenny thought the name was apropos and began calling it Satan’s Gut to avoid the use of numbers. In a flurry of letters exchanged between Dock Marston and Kenny Ross in early 1956 Dock said “A short time back, I had the pleasure of seeing your run of Cat via the movies of Dr. Lambert.” Kenny replied and said that the Frank Wright group had started calling Rapid #26 in Cataract Canyon “Little Lava Falls” and that he had even referred to it as “Nevills Rapid” where one of Norm’s boats, the Joan, had spilled in 1940. But Kenny really liked the name “Satan’s Gut” that had been suggested by one of his passengers. Dock Marston replied and said he liked the name Kenny had come up with and suggested that the apostrophe be dropped.

The usage gained popularity to this day and now Rapid #26 is also known as “SATANS GUT.” Unfortunately, several authors of books about river running have either misstated who named the rapid, or when it was named, or the number of rapids. Just to be clear, the rapid in Cataract Canyon called SATANS GUT, got its name on a Kenny Ross river trip on approximately August 30, 1955! And for further clarification in regards to just how many rapids are in Cataract Canyon, prior to Glen Canyon Dam, Kenny wrote the following to Dock Marston in March, 1956:

My Rapid #26 or SATANS GUT in Cataract is the one pictured opposite page 144 in Kolb’s book (bottom) but according to the USGS map it is not part of the 75-ft drop in 3/4 mile as it is captioned. That this was #24 in Nevills reconning [reconnoitering] is not surprising to me because it would have been about #30 for the Kolbs. Their #22 appears to be my #18. It just aint possible to number those rapids so that everybody comes out right. For example, my #10 simply does not exist at a moderately high stage of water. For the life of me I couldn’t tell you the exact number of rapids in Cataract but it is somewhere between 66 and 74, depending on the water stage and how you want to call ’em.

Dock also agreed with Kenny and other pioneering river runners that “rapids” should be rated on some sort of sliding numbering scale depending on flow.

To comment, scroll to the bottom of the page.

Zephyr policy: REAL NAMES ONLY on Comments!

Don’t forget the Zephyr ads! All links are hot!