THANKS to Tom McCourt & the Tibbetts Family.

For years, I have been watching Moab move farther and farther away from its roots, to the point where it seems few people even know the history of the place anymore. Some of them don’t know OR care, but I think there are still many who have a respect for the past (I hope so, at least).

Last winter I read Tom McCourt’s book on Bill Tibbetts and think it’s his finest work. I knew a bit about Bill,

but the story was told so beautifully and I felt it was a very moving tribute, not just to Bill, but to those far off times.

I see Moab as some alien world now, and I feel the most significant contribution I can make with the Zephyr these days, is to try and preserve the past in some fashion, or at least make it available for those readers who are interested. With Tom’s permission, the Canyonlands Natural History Association who published it, and with the good wishes and approval of Bill Tibbetts’ son Ray and the Tibbetts Family, we are pleased and honored to offer, over the next few months, excerpts from Tom’s excellent portrayal of ‘the Last Robbers Roost Outlaw.” JS

Chapter 6

A Farewell to Arms

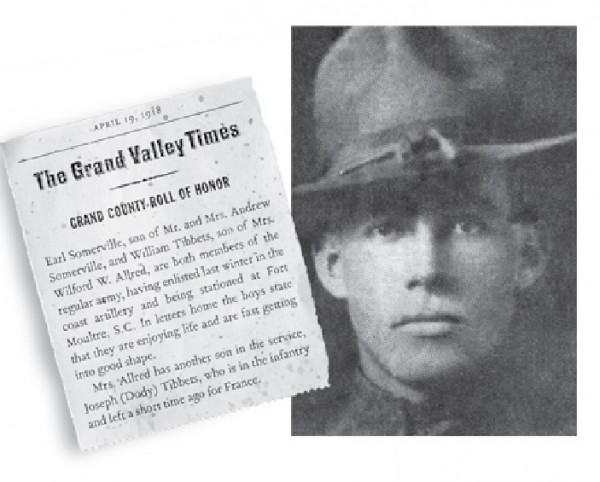

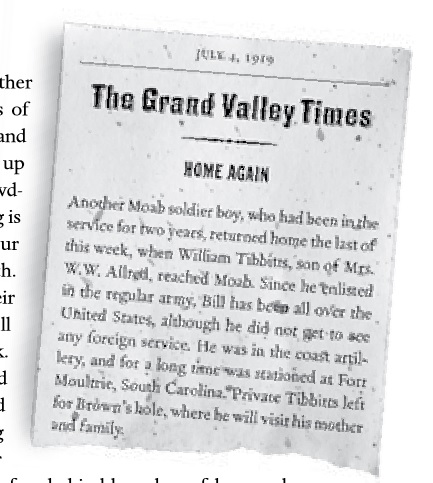

In early summer of 1919, young Bill Tibbetts finally came home. After spending eighteen months at the Utah Sate Industrial School for juvenile offenders in Ogden, Utah, Bill had joined the army. He was nineteen when he put on the uniform. At the time, America was mobilizing to fight the First World War and Uncle Sam was happy to have a few healthy young juvenile delinquents join the ranks. The state of Utah thought it was a good idea, too. What better way to rehabilitate a kid than send him to the army?

Spending time in the army and traveling across the country gave Bill a whole new perspective of the world he lived in. In many ways, he was different when he came home to Moab. He was older, smarter, more world-wise, and more apt to think things through than he had been. He was twenty one-years-old now, five feet, ten inches tall, and well muscled. His bearing, good looks, and commanding personality made him stand out in a crowd. Men stepped aside and women swooned.

But in some ways, the child of the desert hadn’t changed much. He still liked to have a little fun and he was never one to turn down a dare. And he still loved to fight. Bill had been the champion boxer in his army unit. He would take on anybody, inside the ring or out. The toughest kid in Moab had been the toughest soldier at Fort Moultrie, South Carolina.

But now he was home. With juvenile detention and the army behind him, it was time to make a life for himself. Still wearing his army uniform, he went to visit his mother at the homestead in Brown’s Hole.

They were sitting in wicker chairs under the cottonwoods, just the two of them, politely sipping glasses of lemonade, when Amy asked the big question.

“What are you going to do now, Bill?”

“I don’t know, Mom. I’ve saved a little money, but I’m not sure what to do with it yet. I’d like to get a start in the cow business, the way you and Dad did before … well, you know. I think I’d like to run some cows. Trouble is, all the good range is taken. I don’t know where to go to make a start.”

“It’s getting real tough around here.” His mother said wistfully. “We’ve had cows on the foothills of South  Mountain for almost fifteen years now and there seems to be more cows and more cowboys up there all the time. The range is really getting crowded. We’ve been losing a lot of calves, too. Rustling is getting out of hand in these parts. That’s why your dad stayed on the range with the cows so much. We got neighbors who’ll smile and offer their hand when they meet you face-to-face, but they’ll steal your calves the minute you turn your back. Black-hearted, cussed damn people,” she said, and then she smiled weakly with embarrassment and dropped her eyes as if she were ashamed for using such rough and irreverent language in front of her son. A blush came to her cheeks and she hid her face behind her glass of lemonade.

Mountain for almost fifteen years now and there seems to be more cows and more cowboys up there all the time. The range is really getting crowded. We’ve been losing a lot of calves, too. Rustling is getting out of hand in these parts. That’s why your dad stayed on the range with the cows so much. We got neighbors who’ll smile and offer their hand when they meet you face-to-face, but they’ll steal your calves the minute you turn your back. Black-hearted, cussed damn people,” she said, and then she smiled weakly with embarrassment and dropped her eyes as if she were ashamed for using such rough and irreverent language in front of her son. A blush came to her cheeks and she hid her face behind her glass of lemonade.

“Your dad would have put a stop to it,” she said from behind the glass.

“How many cows you got now?” he asked.

“Couple of hundred,” she said proudly. “I’d have a lot more if I had any help taking care of them. Hired hands just don’t do as good a job as I’d like, and with this batch of kids, I can’t spend the time it takes to do it right.”

She took another sip of lemonade and then quietly offered a suggestion. “Maybe we could partner up?” she said, hopefully. “You take care of my cows and I’ll pay you in calves. It would surely help me and it would be a good way for you to get a start.”

Bill promised he would look into it.

Eastern Utah was open range and it was all public domain. Anyone could get in the livestock business and run cows or sheep almost anywhere they wanted. There were few fences and few laws governing the use or misuse of the land. The law of the jungle prevailed. A rancher simply claimed a territory, put his stock there to graze, and then defended his “right” to use that ground against all comers. Those who were tough, determined, and willing to fight usually prevailed. Those who were timid, polite, and less aggressive usually didn’t.

It was a dog-eat-dog world. Dozens of mini-range wars were going on at any given time on any given range. Cattlemen came and cattlemen went. The Taylor Grazing Act, a congressional mandate that created the Bureau of Land Management and put restrictions on where and how many cows an outfit could run, was still several years in the future. The act wouldn’t become law until 1934. Until then, it was a free-for-all on the open range. Young Bill Tibbetts knew he was climbing into the lion’s den when he decided to be a stockman.

Back in Moab, Bill had a long visit with his uncle, Ephraim Moore. Ephraim, too, was in the cow business. He was running a few hundred head on the White Rim below Island in the Sky and along the Green River bottoms, some thirty miles to the south and west of Moab.

“If you want to get in the cow business you can partner up with me,” Ephraim offered as they sat on the porch, watching the afternoon sun melt into the fire of a desert sunset. “You help take care of my stock and I’ll help you get started. We can each keep our own brands and just run our cows together. You own your cows and I own my cows. The two of us runnin’ the herd would be a big help. We could watch out for each other and it’ll save me the cost of payin’ a hired man.”

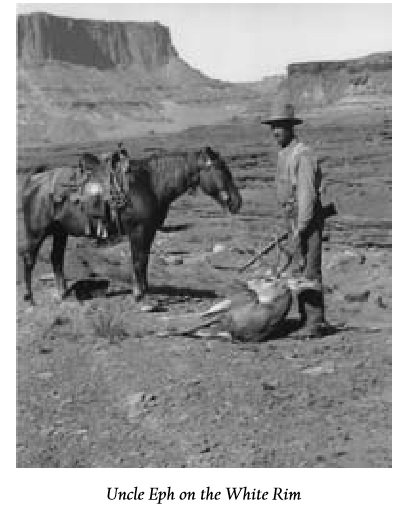

It was a good offer. Ephraim Moore was a good man to partner with. He knew the cow business and the desert around Moab. He knew the other stockmen in the area and the tone and the tenor of local politics and personalities, too. He knew the boundaries claimed by the various cow outfits and he was on good terms with his neighbors, a man with lots of friends and few enemies. Ephraim was known as an honest man, a devout Mormon Elder who went to church often and officiated at most of the baptisms and other church ordinances on behalf of the extended Moore family clan. Like most committed Mormons, he didn’t drink, smoke, or gamble.

But there was a tough side to Ephraim Moore, as well. He played by the rules but never ducked a fight. People respected him. In 1898, while still just a kid, he had joined the U.S. Marine Corps during the Spanish-American War. He was a smaller man than Bill Tibbetts, but lean, wiry, and tough as nails. He didn’t talk much, but when he did, people listened.

Surprisingly, in spite of frequent church attendance, having been raised on the frontier had given Eph a muleskinner’s vocabulary. He sometimes used colorful cowboy cuss words, but never in the presence of polite company. He was the master of his emotions and he could control his tongue when he needed to, or wanted to. But then, sometimes the man just needed to cuss. It got the poison out of his system.

And while he was not a bad-looking fellow, Ephraim was never a lady’s man. Like many of the old-time cowboys, he was a committed bachelor to the end of his days. Bachelorhood was a rare thing for a Mormon Elder in the early 1900s. Brigham Young had taught that it was a man’s duty to marry and have as many children as possible to help build up the kingdom of God on earth.

But to his credit, while remaining single in spite of the matrimonial pressures exerted by his church, Ephraim was a man of impeccable virtue. He didn’t frequent bordellos or the habitations of loose and painted women. He did have a few lady friends during the course of his life, but those he called friends were church-going spinsters, respectable widows, or grandmas of the highest order. No woman was ever able to rope, tie, and tame him. His cows and the desert were his life.

Ephraim Moore was forty years old in the summer of 1919, when he and Bill became partners. He was still young enough to spend weeks in the saddle, but getting too old to enjoy sleeping on the ground.

“I appreciate the offer to partner up with you,” Bill said with real sincerity. “And I’ll work hard, Eph. But I’ve promised Mother that I’d take her cows, too. They’re stealin’ her blind over on the La Sals. That man of hers won’t stay with the darn cows. He spends all of his time in town. Nero fiddlin’ while Rome burns, you know. He never was a cowman, anyway. I’ve gotta get mother’s stock outta there and take care of them while there’s still some to save.”

“I’m fine with that,” Ephraim consented. After all, Bill’s mother was his sister and it was all in the family. “The question is where to go to expand the operation. If you buy a few dozen cows to get started, and with your mother’s stock, we’ll have over 600 head. There ain’t room for that many on the river bottoms where I’ve been runnin’ and the White Rim is full up, too. And if we push any farther north we’ll have to fight every cow outfit this side of the Book Cliffs.

“There’s got to be someplace we can run a few hundred head,” Bill insisted.

“I don’t know,” Eph mused. “All the range around here is all taken up. Everything on the Blue Mountain, Dry Valley, the Big Indian country, and everything north is filled up with cow outfits. And I don’t think you could squeeze another cow into the La Sals. Some of those poor old critters are eatin’ moss above timberline now. There just ain’t no other place for them to go.”

“What’s it like over on the Robbers Roost? I remember the time me and you rode over there to get that stud horse from old man Biddlecome. That’s big country over there. Is the Roost all taken up?”

“There ain’t a lot of water on the Roost,” Eph explained. “And what little there is, old Biddlecome’s got all sewed up. I wouldn’t want to crowd a guy like Biddlecome, anyway. Some guys are best not to mess with.”

“What’s south of Biddlecome?” Bill persisted. “From what I remember, it looked like cedar country way down along the river there. Is there any grass down that way?”

“I don’t really know much about it,” Eph confessed. “From what I’ve seen, it looks like more of the White Rim country – not a great place for cows, but doable, maybe. I’ve heard it called the ‘Laterite’ country. Don’t know if anyone has cows down there or not. People from Hanksville, maybe. One thing for sure though, it’ll be a rough somnabitch. That’s rugged country down along the river there.”

“Well, I guess we better go check it out,” Bill said, very matter of fact. “If we’re gonna get rich in the cattle business, we gotta find a spot to spread out. Can you go day after tomorrow? I got business in town tomorrow.”

“Sure,” Eph said. “I’ll get the camp outfit together and check the shoes on the horses.”

Early the next afternoon, Bill walked into the pool hall on Moab’s main street. He was still wearing his army uniform and his flat-brimmed campaign hat. He found the man he was looking for sitting backwards on a wooden chair, watching a pool game in progress. The man saw him come in and stood up to greet him with an extended hand and a weak but friendly smile. “Hello, Bill, I heard you was home. It’s good to see you back.” Everyone in the pool hall turned to see the handsome young soldier.

Bill ignored the offer of a handshake. “I wanna talk to you outside,” he said with a loud voice and a cold,

deliberate sneer, his hands planted firmly on his hips. The older man stood there in shock and bewilderment with his right hand still extended.

All activity slammed to a stop inside the pool hall. In the sudden silence the sounds of little kids playing in the street echoed through the pool hall. From somewhere across the room a man cleared his throat and put a heavy beer mug down on a tabletop. The clock on the wall thumped like a heartbeat in the silence of the room.

“Sure, Bill, let’s go outside,” his stepfather said very quietly, his brow wrinkled in deep apprehension, his eyes showing fear. Bill turned and walked back outside, the heels of his army boots clicking loudly on the rough board floor. The pool hall emptied into the street. People on the sidewalks hurried over to see what was going on. A crowd quickly gathered.

Outside in the dusty street, Bill took off his army coat and draped it over the porch railing. He carefully set his hat on top of the coat and removed his necktie. He then turned to his stepfather with his jaw set. “You used to beat hell outa me when I was just a little kid,” he said with a dramatic air as he rolled up his sleeves. “And I swore that when I got big enough, I was gonna knock the shit out of you, Winny, old boy. Today is the day. You can take it like a man or I can chase you all over town, but after all these years, I’m here to take you down.”

Winny Allred just stood there for a moment, alone as it were, there in the street, surrounded by a group of his life-long friends and acquaintances. He looked at Bill and then at his friends. None of his friends would look back at him. They all turned their heads or looked at the ground. His rough and ready stepson stood there grinning like an alligator, his fists clenched and his chin in the air, posturing like a confident young gladiator. The young soldier was twenty years younger than his stepfather, bigger, taller, stronger, and infinitely more experienced in the manly art of bare-knuckled boxing. The next move was up to Winny Allred. He didn’t hesitate long.

“I’m not running from you, Bill,” the older man said with real conviction. “You go ahead and beat me to death if it makes you feel any better, but I ain’t runnin’.”

Bill was instantly impressed, and so were the people standing around. Somehow, no one had expected to see such courage in the eyes and the stance of the town’s best fiddle player.

“But before we fight, there’s some things I want to say,” Winny said with a quivering chin below eyes that were fixed and steady. “There’s two sides to every story, Bill. And you wasn’t the sweetest little kitten in the litter. I took your mother in when she was widowed. She was alone with two little boys to feed and I married her and did my best to make her happy and see that she was taken care of. I took you and Joe in, too, Bill, and it wasn’t easy marrying a woman with two little kids. I gave you a home and I did my best to be a father and a good husband.

“And damn it all, I know I’m not your dad. Never will be, couldn’t ever be. But that’s who you and your mother always wanted me to be. I’m not a cowboy, Bill. You know it and I know it. I make my living here in town. I teach music, for Gawd’s sake. I play at weddings and dances and church socials. That’s who I am and that’s who I’ve always been. And I’m sorry I couldn’t be more like your dad. He must have been one hell of a man.

“I tried to talk your mother out of goin’ back out there on the desert and filing for that cussed homestead in Brown’s Hole. But that’s where she wants to be, Bill. She loves that life and I’m not a part of it. But in spite of all that, I still go there in the spring and help to plow and plant and brand and do all of that other farming and cowboy stuff. And I go out there in the fall and help put up the hay and wood and gather the steers and all. But that ranch is her place, Bill. I don’t belong there and you know it. But, by Gawd, I’ve tried.

“And as far as beatin’ you up as a kid. Yeah, I did that. But you had it comin’. You was always the most cantankerous damn kid. And you baited me, boy. You tormented me somethin’ awful. You can’t deny it. You know it’s true.

“So go ahead, beat the hell out of me here in front of the whole town. I’m sure you can do it. But I ain’t runnin’, no matter what. You go ahead and do what you gotta do.”

Bill stood there in his army shirt, his fists clenched, looking into the sad and pained eyes of his stepfather. The older man looked back over his own raised fists and his steady gaze never faltered. Bill looked around at the people gathered to watch. Like they had done to Winny Allred, no one would look back at him. They all turned their heads or looked at the ground, impassively. The only sound was the singing of birds in the nearby trees.

Finally, after what seemed like a long time, Bill put his hands down and turned to get his coat and hat. “I can’t hit a pathetic guy like you, Winny. It wouldn’t be sportin’.”

“Shake my hand before you walk away!” came the challenge from behind him.

Bill turned in surprise to see his stepfather still standing there with his fists up in a classic Victorian boxing stance. “You shake my hand or don’t you dare walk away from here,” Winny threatened. “It ain’t over unless we fight or shake hands.”

Bill stood with his army coat over his arm and his hat in his hand, looking at the older man in bewilderment.

“By Gawd, I mean it, Bill. Don’t you just walk away from here. You shake my hand or let’s get this thing done. We ain’t leavin’ it like this.”

Bill looked at the faces in the crowd. Some were looking back at him now and he could see disapproval and even anger in their eyes. His stepfather was right. Finish it now or forgive, forget, and forever let it be. He had called the man out in front of the whole town. He owed him at least that much.

Bill could see that the crowd was on his stepfather’s side. He would have to leave town if he didn’t do the right thing. If he walked away, the townspeople would never forgive him. He was caught in his own trap, there in front of all those people.

It took a while for the young soldier to muster the courage to swallow some of his pride. “Damn,” he mumbled as he looked at the ground and dug the toe of his army boot in the dirt. He had to think it over for a moment. Everyone knew he could beat Winny Allred, but he just didn’t have the heart to fight the man anymore. Everything his stepfather had said was true and Bill knew it. He was embarrassed and deeply ashamed for having called him out in public like that.

There was nothing else he could do. Bill took a deep breath and walked those long, lonely, and painful steps over to where his stepfather stood waiting. And then he held out his opened right hand. “I will shake hands with you, Winny. And I’m sorry about all of this.”

“Good enough!” Winny said eagerly as he took Bill’s hand in his best imitation of a rough cowboy handshake.

“I’ll buy the beer,” someone called from the edge of the crowd, and everyone started moving back toward the pool hall. A few of the men were patting their pal Winny Allred on the back while talking excitedly.

In just a few moments Bill found himself standing all alone in the middle of the street. He turned and started walking back toward his Grandma Moore’s place. It was time to take off the uniform and put the war behind him. He had finally made peace with his troubled childhood. It was time to start a new life.

All images from the book ‘LAST OF THE ROBBERS ROOST OUTLAWS: Moab’s BILL TIBBETTS’ …By Tom McCourt. Buy the book here.

Click Here to Read the Previous Installments…

To read the PDF version of this article, click here.

To comment, scroll to the bottom of the page.

Don’t forget the Zephyr ads! All links are hot!