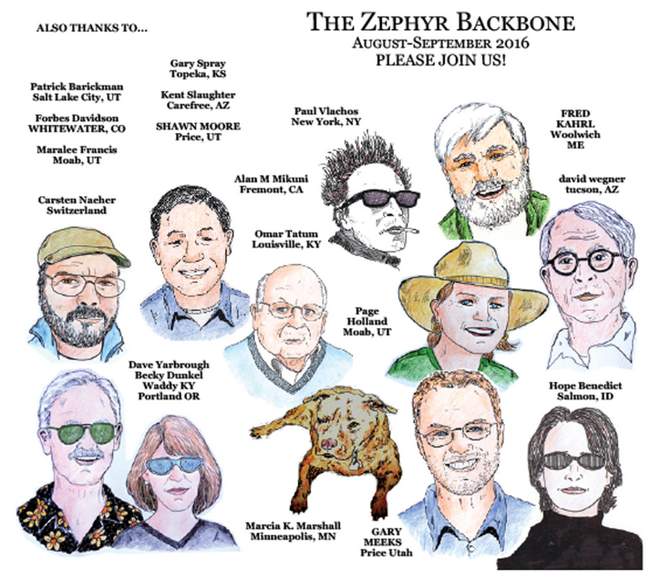

THANKS to Tom McCourt & the Tibbetts Family.

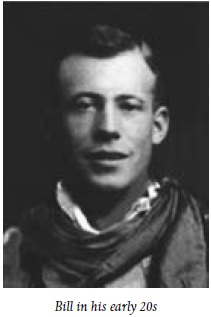

For years, I have been watching Moab move farther and farther away from its roots, to the point where it seems few people even know the history of the place anymore. Some of them don’t know OR care, but I think there are still many who have a respect for the past (I hope so, at least).Last winter I read Tom McCourt’s book on Bill Tibbetts and think it’s his finest work. I knew a bit about Bill, but the story was told so beautifully and I felt it was a very moving tribute, not just to Bill, but to those far off times.I see Moab as some alien world now, and I feel the most significant contribution I can make with the Zephyr these days, is to try and preserve the past in some fashion, or at least make it available for those readers who are interested. With Tom’s permission, the Canyonlands Natural History Association who published it, and with the good wishes and approval of Bill Tibbetts’ son Ray and the Tibbetts Family, we are pleased and honored to offer, over the next few months, excerpts from Tom’s excellent portrayal of ‘the Last Robbers Roost Outlaw.” JS

but the story was told so beautifully and I felt it was a very moving tribute, not just to Bill, but to those far off times.I see Moab as some alien world now, and I feel the most significant contribution I can make with the Zephyr these days, is to try and preserve the past in some fashion, or at least make it available for those readers who are interested. With Tom’s permission, the Canyonlands Natural History Association who published it, and with the good wishes and approval of Bill Tibbetts’ son Ray and the Tibbetts Family, we are pleased and honored to offer, over the next few months, excerpts from Tom’s excellent portrayal of ‘the Last Robbers Roost Outlaw.” JS

Chapter 9

Drought, Indian Trouble, and Murder

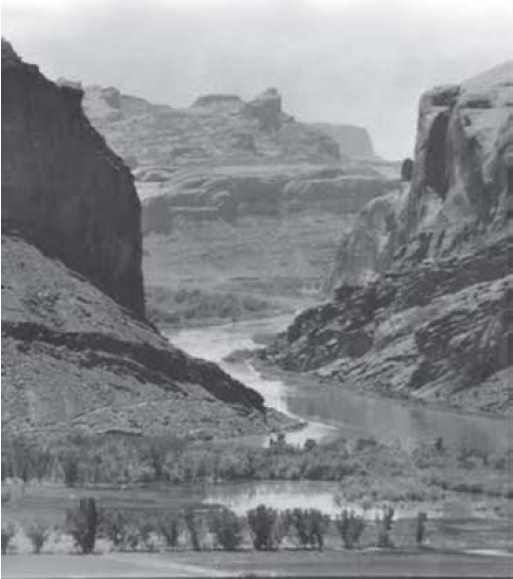

There was a time in eastern utah when rain fell often and the grass grew thick and tall. From the time of the earliest settlers in the Moab area, in the late 1870s, to about 1920, the land was blessed. Pioneers and early stockmen told of grass up to their horses’ stirrups and clear water flowing where none is found today. In those years people dry-farmed the Cisco desert and the river bottoms of the Green and Colorado.

People called it a desert back then, but it was a different desert from what we know today. It was a green and prosperous desert. Deer, antelope, desert bighorn sheep, and wild horses roamed the backcountry and there were willows and cottonwoods along every small watercourse. It was a boom time for the stock industry, and dozens of small towns and ranches dotted the landscape.

Then the rain stopped and the country dried up. It didn’t happen overnight. The climate change came on slowly, little by little and year by year. Every year there was a little less rain and a little less grass. It took a long time for people to understand that the wet years had been an anomaly.

The farmers, ranchers, and sheepmen fought back as best they could, but in the end, dry farms failed, small streams became dry gulches, water wells dried up, and many ranches, homesteads, and little towns had to be abandoned. By the mid-1920s, places like Cisco, Marrs, Danish Flat, Woodside, and Valley City were melting back into the sand. Eastern Utah got an early start on the “dust bowl” years of the 1930s.

The good times had brought tens of thousands of cattle and sheep to the area and they were still there when the rain stopped. With less grass for the same numbers of livestock, the range was soon overgrazed and competition for grass and water became intense. Disputes were inevitable and there was much contention on the stock ranges. The situation was made worse by a lack of laws governing grazing rights and public use of public lands.

Elaterite Basin was hit especially hard. It was a marginal range for livestock in the best of years, and during a prolonged drought it became untenable. In 1923, the grass was short and stunted for want of rain. The blades of green were withered, dry, and parched like straw in the merciless sun. Most of the seep springs went dry and the slickrock water tanks were filling with blow sand. The cattle had to range farther and farther to find water and feed. The miles, heat, and lack of proper sustenance took their toll on the herd. The cows were thin and foot-weary from the constant searching for water and grass.

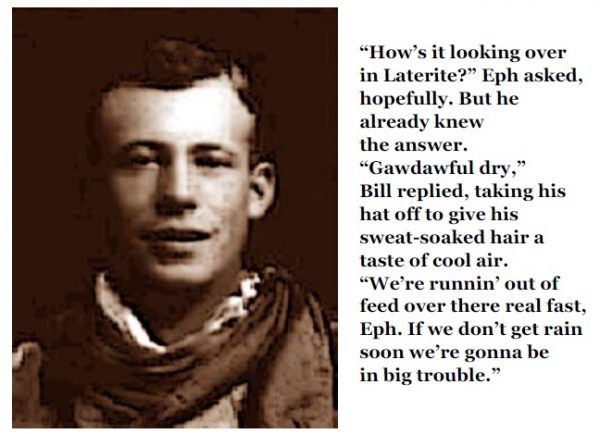

They met on a rough and narrow trail, high above the river. Bill was going north with his packsaddles empty, headed for town. Ephraim was headed south with his packsaddles loaded, going to Elaterite. They hadn’t seen each other for a few weeks so they got down from the horses to talk. The horses were happy to take a rest. The late-July sun was drawing copious amounts of horse sweat and the red rocks beneath their feet were scorched like toast. Eph’s packhorses, especially, took full advantage of the rest stop, leaning from side to side to give one leg at a time a little relief from the heavy loads they were carrying.

“How’s it looking over in Laterite?” Eph asked, hopefully. But he already knew the answer.

“Gawdawful dry,” Bill replied, taking his hat off to give his sweat-soaked hair a taste of cool air. “We’re runnin’ out of feed over there real fast, Eph. If we don’t get rain soon we’re gonna be in big trouble.”

“It’s the same all the way up the river, too,” Eph replied. “I’ve never seen it this dry or this hot. I don’t know what we’re gonna do this winter if the grass don’t grow. We can’t teach these cows to eat sand.”

“What’s it like up on top?” Bill asked, referring to the canyon rims near Island in the Sky. The elevation was much higher there and the area always got more rain and snow than the river bottoms.

“There’s a little grass up there in the Big Flat country, but not as much as normal. I’ve never seen the White Rim this bad either. If it don’t rain soon we might have to sell out. I don’t know what else to do. Better to sell than watch ‘em all winter kill.”

“Let’s not give up too soon, Uncle,” Bill scolded. “We’ve worked too hard to sell out. If we have to, I’ll hire some Navajo to do a rain dance for us. That ought to do the trick. And besides, I’ve got a black cloud that seems to follow me around everywhere. Maybe that cloud will bring us some rain. Let’s give it another month or two before we talk about sellin’ out.”

“Yeah, I guess you’re right,” Eph agreed. “But if the grass don’t get to growin’ purdy quick, we’ve got a big decision to make, ‘long about October.”

“It’ll all work out,” Bill promised.

“Yeah, I guess so.”

“So, how we gonna get past each other on this darn narrow trail?”

“I guess you’ll have to back your horses up,” Eph said with his best poker-faced smile. “My pack saddles are full and I’m not turnin’ around.”

There was Indian trouble that year, too. The year 1923 saw the last “Indian war” ever to be fought on American soil. Again, it happened in Utah’s San Juan County, and like the Indian war of 1915, the whole thing was an unnecessary tragedy.

Early that year, San Juan County Sheriff William Oliver arrested two young Utes for robbing a sheep camp, killing a calf, and burning a bridge. The part about robbing the sheep camp and burning the bridge suggested the Indians might have been guilty of thievery and criminal mischief. The part about killing a calf indicated they were hungry. The ancient Ute hunting and gathering way of life was effectively dead by the 1920s, but the Utes themselves were still alive. And they were caught in a time warp. Their material culture, language, worldview, mindset, religion, oral history, social organization, moral codes, and mitochondrial DNA were still rooted in that older time. The Utes were lost and starving in the modern world.

The two offending Indians, known to the citizens of San Juan only as Sanup’s Boy and Joe Bishop’s Boy, were taken to Blanding for trial. The Indian “boys” were very uncomfortable there, not fully understanding the proceedings and mistrusting the white man’s justice. So, the first chance they got, they ran away. It happened during a noon lunch break when the sheriff was momentarily distracted. What really got the local authorities outraged was the fact that the fugitives had outside help in getting away. Someone had horses waiting for them in the bushes.

It was suspected, but never proven, that Old Posey, a local Paiute chieftain, had assisted in the escape. Posey was about sixty years old at the time and an important leader of the non-reservation Indians still living in southeast Utah. A Paiute himself, Posey was married to a Ute woman, and that gave him

considerable influence with both tribes. The old chief had a long and contentious history with the good citizens of San Juan County. He was known as a troublemaker and had been arrested for playing a role in the infamous “Indian uprising” of 1915.

The sheriff went in hot pursuit of the jail-breakers, but came back a short time later, emptyhanded. The Indians were armed. Shots had been fired and the lawman needed some help. The sheriff promptly deputized “a large number” of well-armed civilian volunteers who formed a posse to hunt the rascals down.

But instead of going directly after the armed and fleeing “hostiles,” the posse went to the nearby peaceful Indian village on Westwater Creek and rounded up about “forty squaws, papooses, and a number of bucks” who were taken to Blanding and held in a guarded “compound” or “stockade” that was actually an open cattle pen. It was late March and the weather was cold and snowy.

Some of the peaceful Indians escaped the Westwater roundup and fled south toward Navajo Mountain on the Arizona border. But most were captured a few days later after a running gunfight when two of them were wounded. The fugitives were taken in cattle trucks to join their relatives in the stock corral in Blanding. A few who got away were able to link up with the fleeing jail-breakers and help with the Indian defense.

Newspapers had a field day. Headlines screamed that Indians were on the warpath and southeast Utah was immersed in bloodshed and violence. Civic-minded citizens from all over the territory were quick to come to the defense of home and hearth. New posse members were signing up daily. Armed with modern hunting rifles, dozens of adventurous young men joined the hunt for “wild Indians” while their womenfolk waited at home with tears and trepidation.

The government did not sit idle while her citizens were in danger. Utah’s governor wired San Juan authorities offering a state-sponsored airplane, complete with machine-guns and bombs, to aid in quelling the “Indian uprising.” General Custer could only have dreamed of such timely and overwhelming reinforcement. The full weight of twentieth century technology, combined with nineteenth century bigotry, was being brought to bear against the natives. Those “murderous redskins” never had a chance.

Old Posey, the aging “war chief,” took charge of the Indian retreat and fought a very good rear-guard defense against the aggressive actions of the posse. At least two lawmen had their horses shot out from under them, and a Model-T Ford was peppered with bullets, one flattening a tire and another “passing lengthwise through the back seat on which three sheriff ’s deputies were sitting.” Amazingly, none of the posse members was injured.

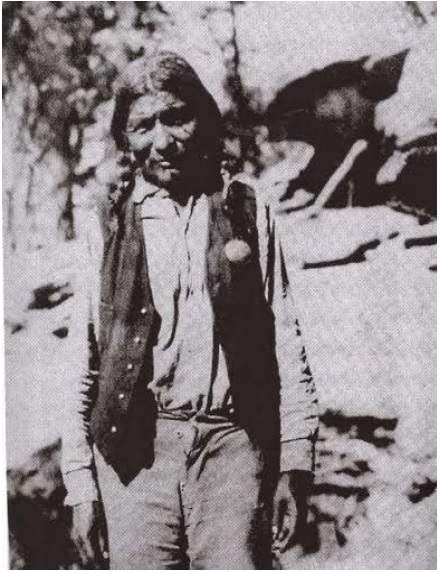

But the Indians were hopelessly outnumbered and outgunned. After a long chase across the desert, Old Posey and Sanup’s Boy, one of the young men who made the jail break, were both shot from long range with modern rifles. The body of Sanup’s Boy was recovered quickly, but Old Posey got away, badly wounded. A U.S. Marshal found his body about a month later.

Old Posey died hard, holed up like a wounded old lion in a secluded patch of junipers on the desert: bleeding, starving, cold, and alone. A fugitive in the land of his fathers, he died without medical assistance or hope for the future, the last of the Native Americans to die in battle in defense of an ancient way of life. Surely, a great assemblage of honored warriors was there to greet him as he walked the star path in the sky to join his ancestors in the land of forever.

Back in Blanding, the Indians held in the stockade, who were guilty of nothing but being Indians, had their children taken away to be sent to an Indian boarding school in Arizona. They were also forbidden to return to their homes and gardens in Westwater Canyon. Instead, each family was given a small plot of land in Allen Canyon, a little farther removed from the white settlements. There, they could starve in peace and quiet solitude.

So ended the last of the Indian wars.

The year 1923 was also a time of major consequence for the Allred, Tibbetts, and Moore families. It was the year Winny Allred was arrested for murder.

Wilford Wesley Allred had a good reputation in Moab and Grand County. He had never been in any trouble. Even the newspaper reporter who wrote the initial story of the murder couldn’t believe the man was capable of murder. He described Allred as “a peaceable citizen.” But he did say that Allred was known to be drinking heavily the past few months, and during a recent trip to Moab, “he did not seem himself.”

Winny Allred and his wife Amy had recently divorced after eighteen years of marriage and six children. The divorce weighed heavily on Winny. The man became so distraught that he gave up his music, sold his musical instruments, bought a small herd of cows, and moved to the family homestead in Brown’s Hole, trying to make amends. But Amy was not receptive to his change of heart. When he showed up at Brown’s Hole, she took the kids and moved to Moab. Winny stayed at the ranch and took up drinking.

The murder happened in January at the ranch in Brown’s Hole. Winny was entertaining friends with moonshine and a hot game of poker. Initially, there were four drunks in the poker game, but soon after midnight, only Winny and a farmer named J.V. Ellis remained in the cabin, still drinking and playing cards.

According to Winny’s confession to the county sheriff a few days later, he and Ellis got into a drunken argument and the bigger man knocked Winny to the floor and beat him severely. The sheriff recorded that Winny’s body showed physical evidence of the beating. Then Ellis began to destroy things in the cabin and throw cast-iron stove lids and fire irons at Winny. In an effort to defend himself, the smaller man grabbed a 30-30 rifle and shot Ellis in the upper chest. The bullet seemed to have no effect on the enraged drunk, so Winny shot him again, this time in the face.

Winny was alone with the body for about twelve hours, until the following afternoon when his brother Hulbert stopped by to visit. Hulbert found Winny deep in despair, sitting near the body of his former friend and neighbor. Hulbert went for the sheriff and Winny was arrested and taken to jail in Monticello. The newspaper said Winny was, “nearly insane with remorse, and has not been able to get any sleep since being placed in the jail.”

San Juan County had a tough time deciding whether to charge the man with first or second degree murder. He was initially charged with second-degree, and might have been released on a $5,000 bond, but before he could raise the money, the charge was changed to first-degree. Winny had to stay in jail without the possibility of posting bail. A trial date was set for late April.

The county had a casual attitude toward prisoners in 1923. Winny could not be paroled, but early that spring he was allowed to go with county deputies and other prisoners to cut cedar posts in the canyons near Monticello. Prisoner work crews were expected to help pay the costs of running the jail. The sheriff made Winny promise that he would not try to escape. Allred was known to be a man who kept his word, so that was the end of the matter.

Unfortunately, Winny was sent to camp early one afternoon to fix supper for the work crew, and while in camp alone, he found a .22 rifle belonging to a sheriff ’s deputy. He shot himself in the forehead, killing himself instantly.

In Moab, the newspaper came to Winny’s defense after his suicide:

“Having known Allred over a long period of time, we cannot conceive of his taking the life of another without having some justification for the act. Quite literally, he was so crazed from drink that he acted on blind impulse or in sudden anger; the true story will now, of course, never be known. Yet Allred’s friends—and he had many friends—will never consider him a murderer…

“…These things we do know; that Allred lived an honest, peaceful life; that he was bighearted, generous to a fault; that he had a high regard for his word, and met his obligations scrupulously. In the face of a record like this, can we, by a mere snap of the finger, brand him as a low criminal and ignore his many estimable traits of character?”

After his mother’s divorce and Winny Allred’s suicide, Bill Tibbetts tried even harder to take care of his mother and help with his younger half-brothers and sisters.

It was late September 1923, and Bill, Tom Perkins, and Uncle Ephraim were camped in a large rock shelter along the Big Water Wash in Elaterite Basin. They were sitting around an evening campfire, deeply engaged in a council of war.

“Between us, we’ve got over a thousand head,” Eph said, staring blankly into the fire. “Considerin’ the dry range conditions and all, I think we ought to sell about half of the herd, at least. With what’s left, we can take a hundred or so up on the White Rim and scatter the rest real thin along the river bottoms. If we can get half of the cows through the winter, we’ll still have a purdy good bunch to start with again next spring.”

“Well, I’ve been with you now for a little over four years,” Bill proclaimed, cradling a cup of coffee in his hands. “But near half of this outfit belongs to me and my mother. And since old Winny Allred shot himself last springtime, these cows are about all she’s got between her and the poorhouse. This is the second time the woman has been up against this. We cut her back by fifty percent and that’ll cut her income, and my income, purdy considerable.”

“Yeah, but we can always save the money and buy new stock when the grass comes back.”

“It doesn’t always work out that way, Eph. You know that. Besides, these cows are ours. They’re home grown and they know this desert country. Hell, we got our own breed started here with that mix of your Mexican longhorn stuff and Mother’s Herefords. It’ll take us another four or five years to get back to where we are right now if we sell half of them.”

“So, what do you suggest?” Eph asked quietly, trying hard not to sound annoyed by Bill’s hardheadedness. “The grass here in Laterite is all burned up by drought. And them sheep outfits will be droppin’ down off the Big Ledge any day now to winter in here, too. There just ain’t no feed, Bill. Sell ‘em or watch ‘em die. That’s how I see it.”

“No, by Gawd. I won’t do it.”

“It’s your only choice.”

“No, Eph, we’ve got another choice. And I’ve been thinkin’ long and hard about it, too. Let’s take this outfit to the best rangeland there is. Let’s move the whole show up on the Big Flat beyond Island in the Sky. You said yourself there’s still grass up there.”

“Oh, good Lord, Bill. You’d have to fight every rancher this side of the Book Cliffs if you moved up on there. That range is old and well established. Some of the biggest outfits in this part of the country are up on the Big Flat. They wouldn’t just step aside and let us in there. No way.”

“It’s public domain, Eph. Those guys can’t keep us out if we decide to go there. They don’t own that grass any more than me and you.”

“Damn it, Bill. They’ve got a first-right to that range. It wouldn’t be proper.”

“Yea, but it would still be legal. I don’t know about you, but legal, moral, and proper get all mixed up when my cows are starvin’.”

“Naw, I don’t like it,” Eph said. And then he stood up and turned his backside to the fire, staring out into the stars and the deep desert night. The faint hooting of an owl filtered in through the cedar trees. One of the horses grazing nearby blew through his nose in disgust.

“You remember that story from the Bible that Grandpa Moore used to read to me when I was a kid? The one about King David and the shewbread in the temple? He read it to me several times because he thought it was so funny when I asked Grandma to make me some shoe bread in one of my shoes. Well, anyway, did you ever listen to what really happened in that story, Eph?”

Eph was still standing with his back to the fire, looking out at the stars. He didn’t answer or act like he was listening to what Bill was saying.

Bill continued without waiting for a reply. Turning toward Tom Perkins, he began: “As I recall, old King David was runnin’ from some bad guys and he was hungry. So were his merry men. They stopped by at the temple for something to eat and the priest there didn’t have any grub. All he had was shewbread, that holy stuff they kept there in the temple for doin’ the sacraments and stuff. Well, David said it was an emergency, and so he took the shewbread and gave it to his troops to eat. David ate it, too. And in the end, the priest said it was okay since it was an emergency and all. Do you remember that story, Eph?”

“Yeah, I remember it,” Eph said quietly, still looking out into the darkness.

“Well, the way I see it, you and me are like King David now. Our cows are hungry like David’s troops. We gotta find ‘em some groceries. I know it’s against the Code of the West to move in on those rich guys up on the Big Flat country, but it’s an emergency. It’s like eatin’ shewbread, Eph. It might have been immoral to do it last year when things were good, but we’re in starvin’ times now and everything has changed. We gotta go where the grass is. If we don’t, we’re gonna lose it all. We’ve worked too hard to give it up and just sell out. I vote we take the whole herd up on top to the Big Flat. I promise to smile and be real polite and try to get along with the neighbors. What do ya say?”

“I’ll have to sleep on it,” Eph said flatly. He then turned and walked toward his bedroll.

To comment, scroll to the bottom of the page.