From a 1988 ‘debate’ in the EARTH FIRST! JOURNAL…

INTRODUCTION by DOUG MEYER

What does this quarter-century old debate from US environmental history tell us? Very simply, honest environmentalism would have played only one role: that of counter-cultural force to the USA.

Edward Abbey reminds us that we abandoned the idea of true wilderness. Certainly no highly-regarded environmentalist today would dare express a philosophy founded on the rights of the non-human world leading to a misanthropic view of a civilization which by definition is unable to value those rights. So is it any wonder that wilderness as biodiversity reserves hasn’t become the operative principle? And though never admitted by environmentalists, wilderness was seen broadly as in fact a human-centered recreational cause. This led to the attack on the language of the 1964 Wilderness Act, exposing it as a naïve white-man’s view of a “pristine” continent.

Wendell Berry reminds us of our inability to express radical thoughts. In “Preserving Wildness,” he wrote that while supporting maximum wilderness designation, he was also pointing out, “as the Reagan administration has done, that the wildernesses we are trying to preserve are standing squarely in the way of our present economy, and that the wildernesses cannot survive if our economy does not change.” (Hint: he wasn’t talking about wind farms and solar panels.) Most failed at deducing the obvious. If enviros had properly understood their highest goals as being antithetical to the USA, they would have plotted for its downfall. Instead, the professionals made themselves a tool of the oligarchy.

It’s very late in the game now; society is circling the wagons and can’t handle this kind of brutal criticism anymore. Though I think Abbey and Berry were somewhat unfair to each other’s positions here, neither was unfair to the bigger truth. I guess all we can do now is smirk at the Good News of the USA’s long predicted demise.

Sincere thanks to Earth First! for permission to republish.

-Doug Meyer

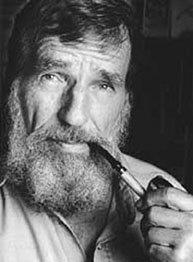

Stewardship Versus Wilderness By Edward Abbey

Stewardship Versus Wilderness By Edward Abbey

HOME ECONOMICS; Wendell Berry; North Point Press, San Francisco; 1987; 192pp.; $20 hardcover.

Most of this book is so good that one hesitates to criticize any of it. In this collection of essays on such topics as farming, marriage, home defense and national defense, nature and human nature, Wendell Berry as always “stands for what he stands on” – the earth. He is in my opinion the best serious essayist at work in the United States; and his poetry and fiction are equally deserving of respect, admiration, and most of all more readers.

Much as I like this book, however, it contains one essay which troubles me. In “Preserving Wildness,” Berry attempts to defend the prevailing notion, characteristic of our homocentric culture, that “stewardship” (or “wise management”) is an adequate solution to our social ills; furthermore, he argues, the tragedy of human population should be seen as a problem not of numbers but of the proper distribution of human settlement over the planet.

Mr. Berry’s essay begins with an attack on the notion that the biosphere is an egalitarian system, wherein each species has as much right to continue to exist as any other. In its place he offers the old formula of “stewardship,” by which the earth and everything on it is to be managed for maximum human benefit, whatever the cost to other forms of life.

This anthropocentric or homocentric view is of course the prevailing one in our society and in all human societies of the last 5000 years. In placing himself “in the middle” on this point of controversy Berry gains plenty of company – the overwhelming majority of the earth’s five billion inhabitants. But he also risks getting lost in the crowd.

The trouble with the concept of “stewardship” is that the stewards tend to think they have the God-given right to exercise domination over the entire planet. If confined to a restricted portion of the earth’s land surface, say about 50%, it might be acceptable, but human vanity is never content with limits. That is why we need extensive regions of true wilderness, free of permanent human habitation and human development. Otherwise our national parks are soon reduced to the status of playgrounds and zoos and our national forests to tree farms, strip mines, and beef-industry pasturage.

Stewardship is not good enough. The US Forest Service practices stewardship. So does the Bureau of Land Management. So does most of our agricultural industry. The results are plain to see: the destruction of wildlife, pollution of land and air and water, encouragement of population increase and industrial expansion, and the gradual degradation of life, including human life, to the role of raw material for the technological culture.

Berry maintains that we have no choice but to use nature. A half truth: we are compelled, as creatures of evolution, to make use of enough of the natural world to sustain our own existence. We too have a right to be here. But only human greed and humanistic arrogance require that all of nature be subordinated to our desires. We retain the option of allowing at least a part of the world to go on in its own fashion without human meddling, whether called “stewardship” or “multiple use” or “scientific management.” The fact that humans – or more exactly, human cultural institutions – now possess the power to control, manage, exploit or colonize every nook and cranny of the natural world does not give us the moral right, even less the obligation, to do so. On the contrary, our immense powers, combined with our belief in rationality and justice, oblige us to tolerate the pre-human and the non-human, to refrain from interfering, to keep our hands off. This is the essence of the wilderness ideal. It is indeed a moral issue, which is why we must teach ourselves to transcend the antique Hebraic superstition that God – or whatever – created the world solely for the pleasures and appetites of the human animal. Let being be.

One look at a mountain lion, or a great white shark, or a snail darter, or a centipede, should suffice to convince even the most obtuse that the world is infinitely more complex and mysterious than merely human desires can explain. The continued existence of these beings – animals and rocks that serve no human purpose – is of course a source of vast resentment to the majority of humankind. Not only do they compete with our instinctive urge to humanize everything, they also create annoying intellectual problems for theologians and technocrats – for all those who still believe that humans really are the center of the universe, the primary object of Creation’s solicitude. Vanity, vanity, thy name is humanism. (Whether Christian or Marxist.)

Certainly we should make wise use of what we must use. But we do not need to hog the whole nation, the entire planet, and then going beyond even that lustful goal, cast covetous eyes and reach out grasping hands toward the moon and other planets. Enough is enough. It is our greedy, expansionistic, industrializing culture, not human nature, which makes monsters of homo sapiens.

Not greed but need, they cry – there are so many of us!

How true. So long as human numbers continue to grow, there is little hope that we can save what wilderness remains in America. Even less hope that we can advance toward a true democratic society of independent freeholders, as Berry fondly imagines, as Jefferson once dreamed of. Still less hope that we could regain the relative paradise of an economy based on hunting, fishing, gathering, with space enough and time enough for all. The population of America has doubled in my lifetime, from 120 million to 240 million, plus who knows how many uncounted aliens hiding in our cities. Unless the population of our country is gradually reduced, through natural attrition, to some optimum figure like 50 million, there is no chance that our democratic ideals can ever be achieved. In the contemporary world, democracy – meaning not merely political participation but a fair share in the ownership and control of wealth for every citizen – remains a fantasy. A fading, receding dream.

It is for reasons such as these that I find Berry’s position on the question of population to be inexplicable. There is a hidden premise in his argument which he is not revealing to us. If he thinks 240 million is not too many, how about 250 million? 300 million? How many do we have to accommodate on our finite land before he will agree that we have reached the point of diminishing returns?

He cannot dismiss the matter by speculating on the possibility of genocide, the deliberate extermination of “unemployables” and “underclasses.” That is a false alternative. The decent, simple, and perfectly fair means for controlling population size in our country are easily available: economic incentives: A revision of the tax system so as to reward single people and childless couples and to penalize those who breed more than, say, two children per family, combined with a system of economic rewards for those who voluntarily agree to some form of reproductive sterilization. We already require a license to drive a car; how much more sensible to require a license for baby production, combined with a stiff tax on motherhood. Most people in our lunatic society are not qualified to beget and raise children anyhow: look about you. Of all American freedoms, the privilege to breed is the one most grossly abused. And the abuse is carried on at public expense, based in turn on the continuing abuse and pillage of our diminishing natural resource base.

On this point, the American public, as always, is far ahead of our cultural institutions, our so-called leaders, and our deep thinkers. Most American women are content with no more than two children apiece; the real cause of our continued population increase is not ignorance but uncontrolled immigration. If immigration were curtailed, as most of our citizens would like it to be, we could soon stabilize the national population and begin a serious reform of our malformed social, economic, and political institutions. But the powerful do not want this; the manic ideology of “Growth” is based upon never-ending population increase; the conservatives love their cheap labor, the liberals love their cheap cause, and the great techno-industrial megamachine requires a never-ending supply of its essential raw material – bodies – in order to justify its expansionist logic.

And the world continues to shrink. Human life becomes ever more debased – here and everywhere. Crowding is accepted as the norm, queues become commonplace, the roar of the traffic grows louder, and the value of the individual life is steadily cheapened as the total number of human lives is steadily compounded.

That is where the philosophy, or rather the religion – it hardly deserves the name philosophy – this is where the religion of human vanity, of man as the center of all things, has brought us.

Mr. Berry asks us to respect the human species. But respect has to be earned. I respect my friends, I love the members of my family – most of them – but somehow I cannot generate much respect, love or even sympathy for the human race as a whole. This mob of five billion now swarming over the planet, like ants on an anthill, somehow does not inspire any emotion but one of visceral repugnance. The fact that I am a part of this plague gives me no pride.

Indeed, there are too many of us. Man has become a pest. For the dignity and decency of all, we must reduce our numbers to a sane, rational, humane and human level. Otherwise we are no better than rabbits, or fruit flies, or bacteria in a culture bouillon, and deserve a similar fate, the natural fate of any animal which outbreeds the carrying capacity of its range. As individuals we seem capable of common sense, of reason, of sympathy for others, but as a race, as a species, we have yet to prove that we can behave any better than tent caterpillars devouring the tree which supports them.

Page 32. Earth First! February 2, 1988

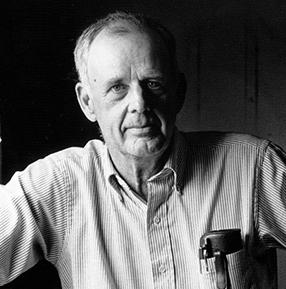

My Answer to Edward Abbey

By Wendell Berry

I don’t recognize my essay, “Preserving Wildness,” in Edward Abbey’s description of it. Certainly, I have never written a word to suggest “that all of nature be subordinated to our desires.” Nor have I ever  recommended that we should “hog the whole nation, the entire planet, and then … the moon and the other planets.” Indeed I have spent the greater part of my life in opposing such subordination and hoggishness.

recommended that we should “hog the whole nation, the entire planet, and then … the moon and the other planets.” Indeed I have spent the greater part of my life in opposing such subordination and hoggishness.

About half of Mr. Abbey’s quarrel with me has to do with his misunderstanding of the word ‘stewardship,’ which, he says, means that “the earth and everything on it is to be managed for maximum human benefit, whatever the cost to other forms of life.” He associates it with “the antique Hebraic superstition that God – or whatever – created the world solely for the pleasures and appetites of the human animal.” And he claims that it is practiced by the US Forest Service and the Bureau of Land Management. There are several things wrong with this.

A steward is someone who takes care of property belonging to someone else. A steward, therefore, cannot manage property for his or her own benefit, maximum or otherwise. According to “the antique Hebraic superstition” to which Mr. Abbey refers, the someone else whose earthly property human stewards are to take care of is God, who made the world for His pleasure (see, for instance, Genesis 1 and Revelation 4:11), and who has retained title to the whole of it; nowhere in the Bible are humans given any part of the earth to do with as they please. Moreover, God is not represented as an absentee landlord, but as an active participant in the lives of His creatures – or, more accurately, their lives are understood as participating in His life: “The young lions roar after their prey, and seek their meat from God.” (Psalm 104:21) To be sure, Adam is given “dominion” over “every living thing” in Genesis 1:28; but this gift is strictly (and dangerously) conditional. There is nothing in the Bible to suggest that “dominion” means the right to use to excess or to misuse anything whatsoever.

I see no inconsistency between this idea of stewardship and the idea of wilderness preservation. Indeed this idea of stewardship seems to me to require wilderness preservation of the same sort advocated by Mr. Abbey. To look to government bureaus to for an understanding of stewardship is to look in the wrong place.

I do not believe, of course, that the biblical idea of stewardship is the only ideal applicable to conservation issues. But it is applicable, and (if taken seriously) it is adequate. It has, moreover, the value of belonging intimately to our language and cultural tradition. I would be happy to see it acknowledged by the religious organizations, which mainly ignore it.

Mr. Abbey’s review would lead readers to believe that my essay opposes wilderness preservation. In fact, I have always been a friend to that cause. The essay to which Mr. Abbey objects contains a lengthy passage on the need to preserve wilderness, in support of which I quoted Mr. Abbey himself. How much of the remaining wilderness should be preserved? All of it, I would wish. I would not willingly part with any of it. On this issue I have always agreed with Mr. Abbey.

Mr. Abbey ignored what I wrote about preserving wilderness, I suppose, because I also argued in my essay that wilderness preservation is not adequate to the preservation either of wildness or of wilderness; I said that if we do not come to better ways of using the parts of the world that we use, we will inevitably destroy all of it, the wilderness included. To me, this is merely obvious. In my part of the country, anyhow, we cannot have any considerable acreage of wilderness merely by preserving old growth woodland. Most of that is long gone. If we are to have wildernesses – and I hope that we will have them, large and small – we will have to grow them. We will have to learn to befriend thickets in honor of what they may become in 200 years. And this will require us to alter profoundly our understanding of farming and forestry, as arts and as economies.

But the issues of use and preservation are more closely connected even than that. Wildernesses cannot be preserved indefinitely by fencing out their would-be destroyers who, in the meantime, wreck the countryside elsewhere. It seems to me that an interest in wilderness preservation implies a need to interest oneself in the best ways of using the land that must be used – timber management, logging, the manufacture of wood products, farming, food processing, mining. The respect that preserves wilderness might have as one of its proper sources, and one of its surest safeguards, a respectful and skillful kindness towards land in use.

A reader who read Mr. Abbey’s review without reading my book [Home Economics] might also conclude that I advocate overpopulation. Here, I think, I had better quote myself. On page 149, I wrote: “I would argue that, at least for us in the United States, the conclusion that ‘there are too many people’ is premature, not because I know that there are not too many people, but because I do not think we are prepared to come to such a conclusion.” (That is a straightforward and reasonable statement. Mr. Abbey accuses me of arguing from “a hidden premise.” I think he suspects me of being a Catholic.)

The conclusion that there are “too many people” in the US is premature, I think, because we have not dealt at all with the issue of use. I do not mean simply the issue of how much to use, but also the issue of how to use. If we reduced our population to 50 million and still refused to curb our technological ambitions and our greed, then we would still have “too many people.”

The conclusion is premature also because we are not talking about the problem with the proper respect for human beings and human nature. “Birth control,” so far, is an extremely crude industrial invasion of the human body, exactly parallel to industrial invasions of our forests and farmlands. It has been extremely lucrative to a few at the cost of damage and diminishment to many. Birth control, divorced from sexual responsibility, is the internal equivalent of clearcutting or stripmining, and is sponsored by the same kind of mind.

I believe that I understand Mr. Abbey’s misanthropy; I think I share his exasperation and resentment; I too long to preserve the possibility of solitary quiet in places wild and unbothered. But I don’t think that misanthropy is a solution, or that it can lead to a solution. Of course it is hard to love people who are not our friends and relatives, but imagination informs us that everybody is somebody’s friend or relative. Of course human history is a sorry spectacle, not the least bit improved in our time, but the same history informs us that some humans have been splendid and that many have been decent. For those reasons, humans have a right to exist that is respectable. I don’t believe that we can preserve ourselves or our world by belittling ourselves.

Mr. Abbey begins his review with an extremely generous compliment to me and my work. This little rejoinder has by no means carried me beyond my gratitude for that – or for his work, which is an indispensible source of delight, instruction, and comfort to me. In spite of the differences that are the subjects of this exchange, I will continue to think of myself as his ally and friend.

Wendell Berry is one of the most highly regarded writers in the US. Along with this, he shares with Ed Abbey the distinction of being one of the dwindling number of writers who eschew the computer in favor of the typewriter.

To read the PDF version of this article, click here.

To comment, scroll to the bottom of the page.

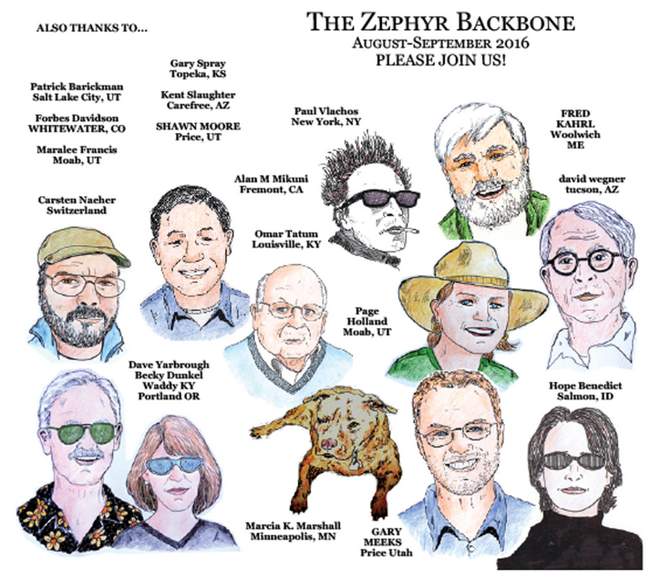

Don’t forget the Zephyr ads! All links are hot!

[…] subject I’ve helped to publish has contained articles speaking about environmentalism. One in all my favourite articles from this subject, the truth is, incorporates two disagreeing essays between two legendary […]