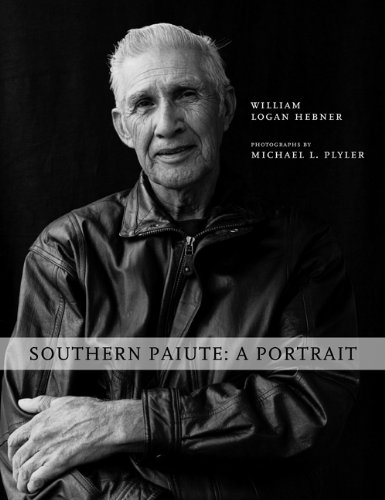

An excerpt from a new book from Utah State University Press

SOUTHERN PAIUTE: A PORTRAIT

William Logan Hebner photographs by Michael L. Plyler

In 1990 the Kaibab Paiute turned down hundreds of millions of dollars by refusing to allow a hazardous waste incinerator on the sliver of ancestral lands they still held, along the North rim of Grand Canyon. It was elder Bill Tom’s final wish that they deny the incinerator. All night they sang to Bill’s confused soul, guiding him through the landscape of the dead, helping him leap to the next world. Impressed by their decision, their ceremony, I asked to see interviews of different elders. That they didn’t exist was the genesis for this book.

There was no notion of a book then, of what would happen if you stacked thirty such stories and portraits together. It began as triage, a sprint towards simply collecting and preserving the life stories and portraits of a remarkable generation passing on. I crammed ethnographic, historic, religious and environmental information for context. Most important, and most difficult of course, was finding elders from this deeply private tribe willing to talk. Fortunately, I can’t think of anyone better than Michael, whose portraits I’ve admired for decades, to make something happen with. He did a lot of heavy lifting here.

Steep learning curves everywhere, especially when we immediately collided with the Southern Paiute’s poster child for dysfunctional white history, the Mountain Meadows Massacre. Most of Southern Paiute “history,” different massacres, loss of lands, untangling their strange braiding with the Mormons, remains raw, emotional and unresolved. This project initially took shape as a local portrait/biography exhibit for a Utah museum, complete with funding. When the museum heard we were gathering their Mountain Meadows stories, they cancelled both funding and exhibit. It almost ended right there.

All this, however, just led us deeper down the rabbit hole, trying to figure how such an astonishingly lame cover-up story blaming the Paiute could survive for a hundred and fifty years. We quietly began meeting with LDS historians and airing the Paiute stories, which continues to pry this story towards resolve. I belabor this because it’s how the project morphed into a book. Two things happened; John Alley, publisher at Utah State University, saw the exhibit and envisioned a book encompassing the whole Southern Paiute confederation. Second, it had taken twenty years just to get a toehold with them here on the Colorado Plateau; I couldn’t imagine why bands from Great Basin and Mojave Desert would open up. Turns out they appreciated our involvement, hence this lovely book (thank you Sandy Bell for the great design).

Despite these painful histories, they celebrate life, their ancient culture, their families, their lands. What does happen when you stack thirty-two images and stories of elders from an American desert tribe? I have no idea. What I keep seeing, keep thinking about, is how deceptive the depth of a culture can be, the appalling amount of pain a tribal people can endure, with dignity and humor, if they remain firmly embedded in their lands, the myriad insanities that devolve once severed from them, and that it’s increasingly clear we need to collectively fire up that dormant connection. Ahora.

Speaking at book promotionals, two themes keep repeating; how invisible they remain, and the simple grace and power of voice, of a story honestly told. As Vivienne Jake, a Kaibab elder, says: “These are real stories and have already had an effect on the unfolding of the world… Open up these lives and let their truths speak to you.”

Logan Hebner

Madelan Redfoot

I was supposed to have died when I was young. I had whooping cough really bad. The doctor said he could do nothing and sent me home. That night my mom’s uncle who had passed away, Kanosh John, came to her in a dream and told her how to bless me before sunrise. I got healed. He blessed me from the spirit world. He made me live. Mother said I wouldn’t have made it through the next day.

I was supposed to have died when I was young. I had whooping cough really bad. The doctor said he could do nothing and sent me home. That night my mom’s uncle who had passed away, Kanosh John, came to her in a dream and told her how to bless me before sunrise. I got healed. He blessed me from the spirit world. He made me live. Mother said I wouldn’t have made it through the next day.

He had a real good medicine. Strong. So powerful that when he’d start his meeting, he’d put an eagle feather down and it would stand up and dance when he’d start singing. My mom used to say when his car broke down he’d take the whole thing apart, piece by piece, and he’d put it back together and it would run.

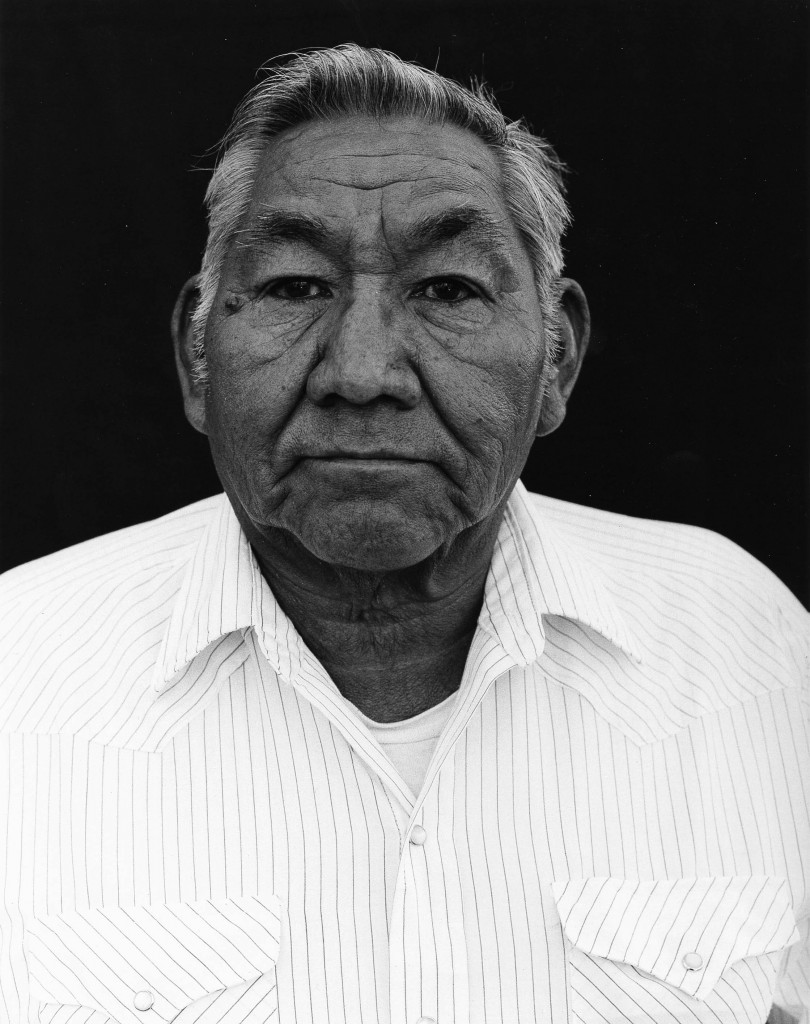

McKay Pikyavit

To receive the power to sing the Cry Song, I don’t think we’ll get that back. My uncle tried to receive them. He said; “I had to get out of there, I couldn’t take it.” It was the only thing he was ever afraid of. He could sing them. But you don’t have the things that go with it, that power. That was destroyed back when they started setting off atomic bombs in the Nevada desert there. That affected the caves.

To receive the power to sing the Cry Song, I don’t think we’ll get that back. My uncle tried to receive them. He said; “I had to get out of there, I couldn’t take it.” It was the only thing he was ever afraid of. He could sing them. But you don’t have the things that go with it, that power. That was destroyed back when they started setting off atomic bombs in the Nevada desert there. That affected the caves.

White man took over this land. Why didn’t we share evenly? Land, water, instead of taking it all over. That’s the way Indians were. Kill a deer, share the deer. Now we don’t do that. They just said you clowns get out of here. It makes me mad. Now Indians are learning how to be a White man. Take everything you can. Steal everything you can. All about getting the chingaliras. I’ll be mad til the day I die.

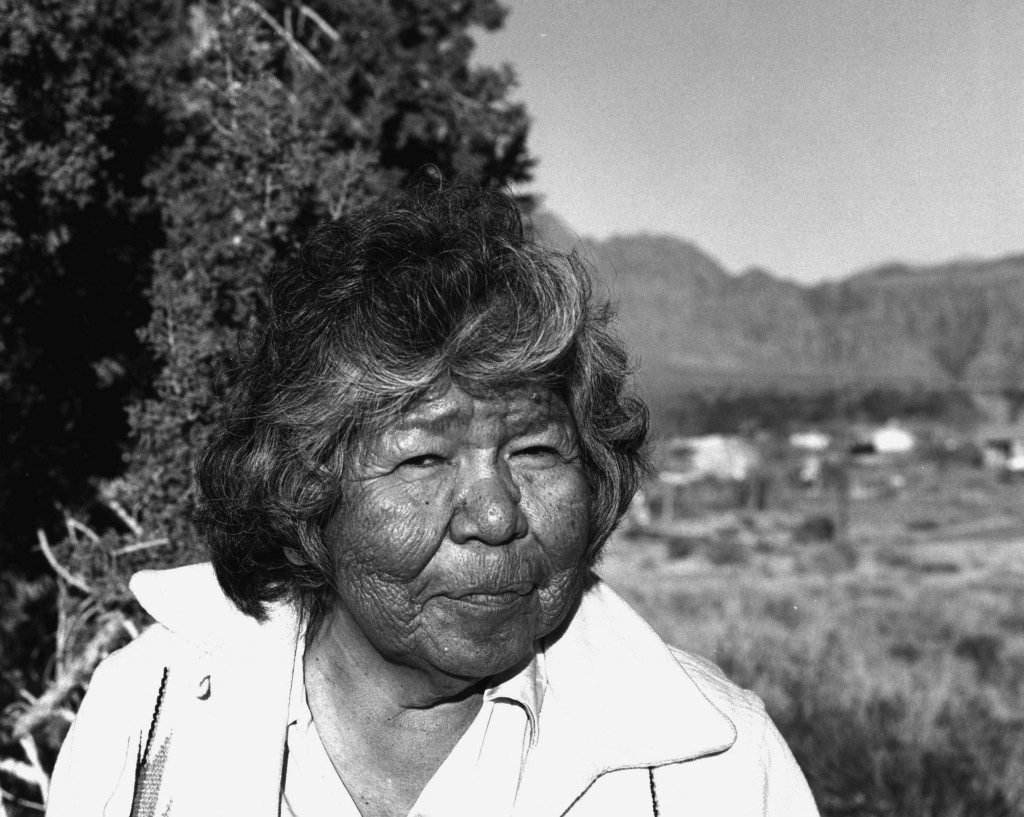

Eunice Tillahash

The Indian doctor as soon as he got out of the car he start chanting, dancing, dancing, old man, old, dancing into the house when my dad was laying there, dance around him. Then he said get his two daughters over here, put them behind me, tell them to dance behind me. Me and my sister went behind him. Then he blow it away, clap his hands and rub together like this. Before he went out he had a big wad of pus, green pus. Then he dance again, dance again. Next night the man dance again, dance again. Then he said; “Okay, that’s it. I’m finished you can take me home.” They paid him, they all donated money, give it to him, then take him back to Moapa. Then my dad got all right. Then it’s when he change, then my dad believe the Indian ways.

The Indian doctor as soon as he got out of the car he start chanting, dancing, dancing, old man, old, dancing into the house when my dad was laying there, dance around him. Then he said get his two daughters over here, put them behind me, tell them to dance behind me. Me and my sister went behind him. Then he blow it away, clap his hands and rub together like this. Before he went out he had a big wad of pus, green pus. Then he dance again, dance again. Next night the man dance again, dance again. Then he said; “Okay, that’s it. I’m finished you can take me home.” They paid him, they all donated money, give it to him, then take him back to Moapa. Then my dad got all right. Then it’s when he change, then my dad believe the Indian ways.

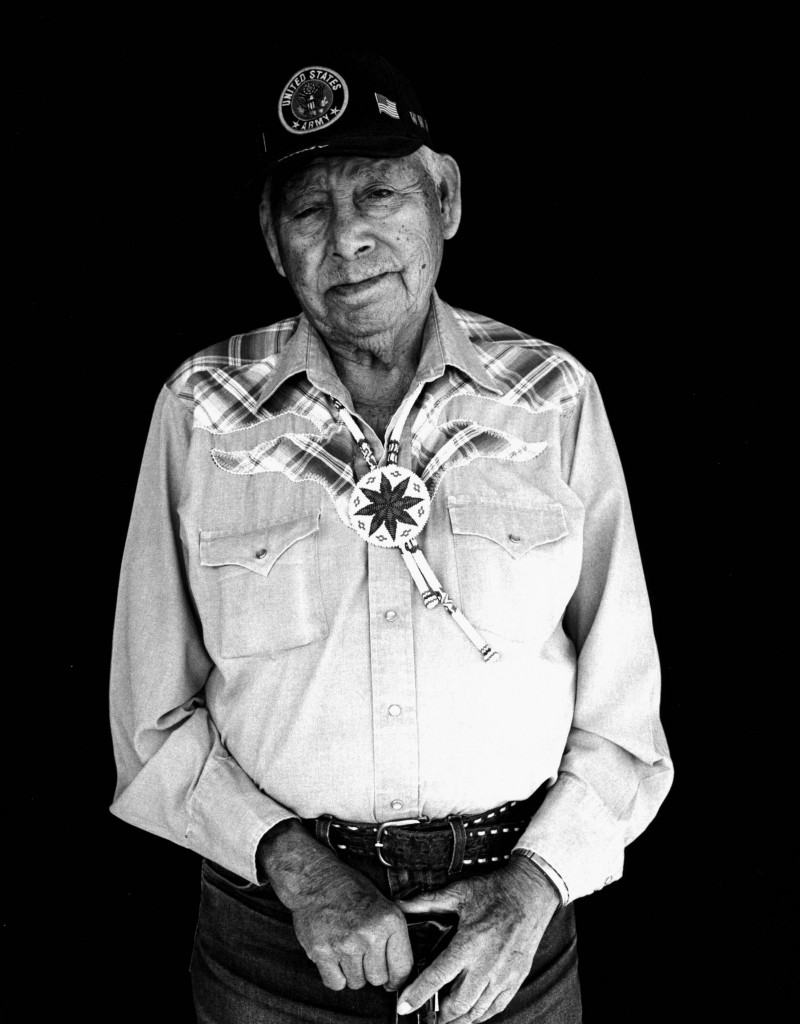

Roger Benn

But I dreamt a lot of things. I dreamt my nephew’s wife died; she died in a car accident. They were coming down the old road, the hill, I could see it in my dream. I really didn’t know who got killed, but the more I dreamt, I saw the casket on the reservation, and it was a lady they said, and I knew it was her.

But I dreamt a lot of things. I dreamt my nephew’s wife died; she died in a car accident. They were coming down the old road, the hill, I could see it in my dream. I really didn’t know who got killed, but the more I dreamt, I saw the casket on the reservation, and it was a lady they said, and I knew it was her.

I dream I’m flying. My dad used to say you’d live a long time when you fly. He lived quite a ways, quite a few years. Like when you get in trouble, you get away, you fly. They say even whites dream too, mentioning things going to happen. Just comes that way I guess. I don’t dream like that no more, so I’m getting close to where I’m going. All I am is still here. My father told me what to do when you dream like that. You get up before sunrise. He told me what to do, to pray, when the sun comes up. I did.

Jack and Mary Ann Owl

JACK: I remember the Navajo family that took over the mountain, his name was One Salt. He would move through here on horseback and get ashes from different sweat lodges that used to be Paiute. He would bring these ashes up and say these are from the Navajo sweats. Archeologists found a Paiute woman’s bones close to a cave and they said they were from prehistoric people, like Anasazi. They were Paiute bones.

JACK: I remember the Navajo family that took over the mountain, his name was One Salt. He would move through here on horseback and get ashes from different sweat lodges that used to be Paiute. He would bring these ashes up and say these are from the Navajo sweats. Archeologists found a Paiute woman’s bones close to a cave and they said they were from prehistoric people, like Anasazi. They were Paiute bones.

I went on a boat with a Navajo translator to where they were planning to build a trading post, close to Bullfrog. Where we crossed the river the Paiute had a rock cairn. That Navajo translator claimed they were ceremonial Navajo rocks. Way back, there were no Navajos. And Navajos never used to do that kind of medicine.

MARYANN: The land is changed from when before the Navajos came. When they first came, they didn’t have any livestock, sheep or horses. The land was still young, it was different. But now their livestock eat everything. Same with the river. When we were young, we’d go down there all the time. When the Anglos closed the dam, Lake Powell, the water came on top of where our ancestors were buried. It is no good.

8.5 x 11, 208 pages, ISBN 978-0-87421-754-4, cloth $34.95

8.5 x 11, 208 pages, ISBN 978-0-87421-754-4, cloth $34.95

ISBN 978-0-87421-755-1, e-book $28.00

Signed copies are available.

Contact us at:

(435) 797-1362 or

d.miller@usu.edu

To view this article as a PDF, click here: aug11-28-29

“Now Indians are learning how to be a White man. Take everything you can. Steal everything you can. All about getting the chingaliras. I’ll be mad til the day I die.”

Ouch.