“As far as technological culture is concerned, we lag miles behind America. But all that is frightfully costly and already carries the germ of the end in itself.” – Swiss Psychiatrist Carl Jung, 1909

On Valentine’s Day, 1884, when he was in his mid-20s, Theodore Roosevelt’s mother and wife both died. In his grief he sought refuge on a cattle ranch in western North Dakota that he had invested in the year before. To comprehend the depth of the place’s remoteness when he was there we have to think of vast stretches in Alaska or Nunavut in far northern Canada. And he could not have had a more improbable background for such an adventure, being Harvard educated and from a wealthy New York family. Yet to his enormous credit he dug in and stayed out on that strange land for much of the next three years.

And in the process he lost over half of his sizeable investment in the ranch due to the terrible weather for cattle. In spite of that, being out on that landscape changed him: “I have always said I would not have been President had it not been for my experience in North Dakota…It was here that the romance of my life began.”

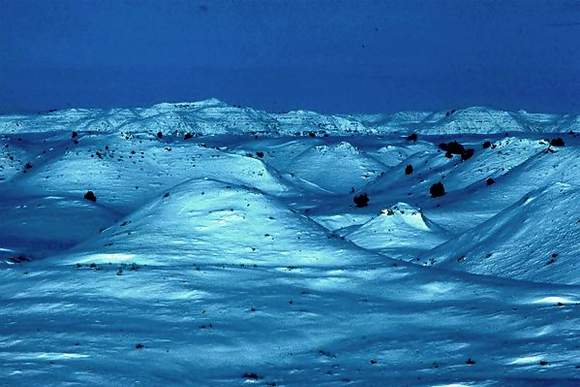

Consider how he described being in that immense place: “Nowhere, not even at sea, does a man feel more lonely than when riding over the far-reaching, seemingly never-ending plains; and after a man has lived a little while on or near them, their very vastness and loneliness and their melancholy monotony have a strong fascination for him…The farther one gets into the wilderness, the greater is the attraction of its lonely freedom.”

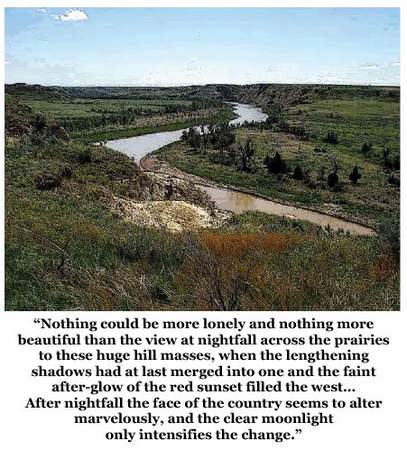

And: “Nothing could be more lonely and nothing more beautiful than the view at nightfall across the prairies to these huge hill masses, when the lengthening shadows had at last merged into one and the faint after-glow of the red sunset filled the west…After nightfall the face of the country seems to alter marvelously, and the clear moonlight only intensifies the change. The river gleams like running quicksilver, and the moonbeams play over the grassy stretches of the plateaus…The Bad Lands seem to be stranger and wilder than ever, the silvery rays turning the country into a kind of grim fairyland.”

Can you see the transition going on here? First Roosevelt encountered the odd, shocking loneliness, the overwhelming silence that fills all wild country. Many people find exactly this experience uncomfortable if not scary and quickly back out. But Roosevelt sensed something in it and stayed until it got into his bones: “There are no words that can tell the hidden spirit of the wilderness, that can reveal its mystery, its melancholy, and its charm.” That’s spiritual solitude.

It’s remarkable that as a young man one of our Presidents experienced this and it altered the way he saw the world.

For example, his profound joy in wild creatures: “One bleak March day…a flock of snow-buntings came…Every few moments one of them would mount into the air, hovering about with quivering wings and warbling a loud, merry song with some very sweet notes. They were a most welcome little group of guests, and we were sorry when, after loitering around a day or two, they disappeared toward their breeding haunts…Now and then we hear the wilder voices of the wilderness…the coyotes wail like dismal ventriloquists…”

As well as his sorrow at what the hand of man could do: “The extermination of the buffalo has been a veritable tragedy of the animal world.”

Roosevelt left North Dakota acutely aware of the vulnerability of wild country to human destruction: “We are prone to speak of the resources of this country as inexhaustible; this is not so.” And: “Of all the questions which can come before this nation, short of the actual preservation of its existence in a great war, there is none which compares in importance with the great central task of leaving this land even a better land for our descendants than it is for us.” To this end he established five National Parks, 18 National Monuments, 51 Federal Bird Reservations, four National Game Preserves, and 150 National Forests.

***

Fast forward a hundred years and some extra. Let’s see if we’re leaving the landscape Roosevelt treasured a better land for his descendants than it was for him.

North Dakota’s Theodore Roosevelt National Park was created in 1947. At 70,447 acres it’s not a huge place. It is divided into three segments: the South Unit, running along Interstate 94; the North Unit, mostly a wilderness area, roughly 50 miles up along U.S. Highway 85; and the tiny Elkhorn unit somewhere between them, encompassing Roosevelt’s ranch. The park is largely surrounded by the much more extensive Little Missouri National Grassland, managed by the U.S. Forest Service.

In 2013 the park had 545,090 visitors, significantly fewer than the 998,849 in its peak year of 1972. The access afforded by Interstate 94 explains the level of visitation despite the otherwise isolated location. My best guesstimate is that the South Unit takes a clear majority of the visitation hits, leaving meaningful wildness of the land up in the North Unit; perhaps at times in the other two.

So it was until the North Dakota shale oil boom. Since roughly 2008 hydraulic fracturing and directional drilling techniques have opened up the Bakken shale formation to massive drilling for oil. The state is undergoing a black gold rush and is now the second highest oil producing state in The U.S. Over 600 wells have been punched into the Little Missouri Grassland itself on leases granted by the U.S. Forest Service.

With these results: at night, from within the park’s boundaries, the visitors can see orange flares from 25+ oil wells that are burning off natural gas, thereby obscuring their view of the night sky. Also, noise from drilling operations can be heard inside the park and tanker trucks for fracking fluids cram once remote, silent roads.

***

It would be sad enough if these oil wells were only shattering the sacred stillness in Theodore Roosevelt National Park that Roosevelt himself understood so deeply. But there is much more. By the time the shale oil boom in North Dakota took off it was well established that enough fossil fuel reserves had already been discovered to make this planet a bleak place if not uninhabitable if they’re all burned.

Which makes discovering any more exceedingly dangerous.

Nevertheless, when the advanced technology – hydro-fracking and directional drilling – came along that made it possible to discover and then produce enormous quantities of oil in the Bakken shale formation, a critical mass of humans could not restrain themselves. And so they’ve been as busy as ants in an anthill discovering and producing ever more of it. Hence the North Dakota oil shale boom.

Of course it’s rationalized in the typical ways. First, producing oil from shale formations is immensely profitable, and profit is always good for shareholders, isn’t it? Second, it provides jobs aplenty that pay well and what could be more American than “good-paying” jobs? And third, America needs its own supply of fossil fuel and we can’t depend on unstable foreign governments in Venezuela or the Middle East to keep providing it to us. You get the drift.

Although this is a disappointingly narrow and short-sighted outlook, its scope is breathtaking when you consider what it ignores. First, the planet’s atmosphere and oceans and ecosystems don’t give a damn about our national or state boundaries or human politics anywhere. Second, they couldn’t care less about our short-term fixations because they are comprised of long-term chains of cause and effect: meaning that the warming and climate instability that harasses us will devastate our young children and will likely kill many of our soon-to-be born grandchildren. And devastate and then kill countless numbers of innocent people and creatures and ecosystems across the world.

The oil shale boom in North Dakota is a psychological and spiritual CAT scan that reveals more about our collective destructiveness than we’re happy knowing about. Particularly because we’ve always thought we were the good guys.

***

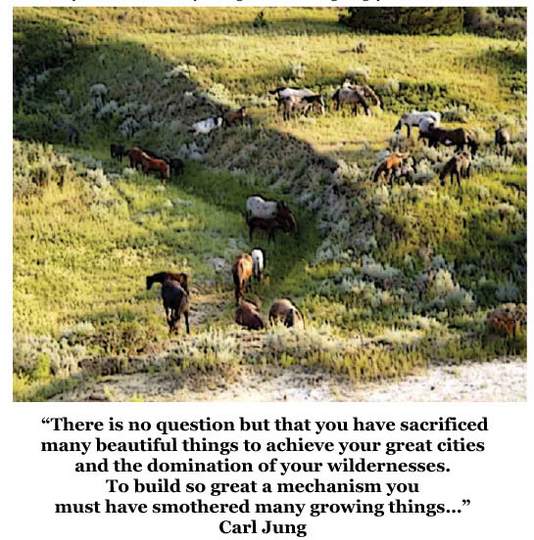

One of the reasons I admire the psychiatrist Carl Jung so much is that early on he spotted a tendency within Western societies and within Americans in particular to become preoccupied with technology and machinery and to utilize it in an unbalanced way. Here is what he said to us in 1912: “There is no question but that you have sacrificed many beautiful things to achieve your great cities and the domination of your wildernesses. To build so great a mechanism you must have smothered many growing things…

…

“…America does not see that it is in any danger. It does not understand that it is facing its most tragic moment: a moment in which it must make a choice to master its machines or be devoured by them….” (Meredith Sabini, Ph.D., Editor. The Earth has a Soul: The Nature Writings of C.G. Jung, 2002, pp. 142-143.)

Jung saw such a one-sided psychological development within us primarily because of our estrangement from nature. Unlike so many Europeans of his day, he knew that an emotional and physical bond with the uncontained natural world, what I call the wildness of the land, has a grounding effect and imparts a strange, indescribable contentment that Roosevelt himself experienced and described so well. And that no machinery or technology, however fascinating and powerful and pervasive it may become, and no matter what material benefits it may provide, can compensate for that dissociation from nature.

In 1930 Jung elaborated on this point in a seminar for his English-speaking students: “…In building a machine we are so intent upon our purpose that we forget that we are investing that machine with creative power. It looks as if it were a mechanical thing, but it can overgrow us in an invisible way, as time and again in the history of the world, institutions and laws and have overwhelmed man. Despite the fact that they were created by man, they are dwelling-places of divine powers that may destroy us.”

…

“…After a while, when we have invested all our energy in rational forms, they will strangle us. They are the dragons now; they became a sort of nightmare. Slowly and secretly we become their slaves and are devoured.” (p.149.)

Jung’s friend Ochwiay Biano of the Taos Pueblo in New Mexico described this phenomenon when they met in 1925, from which I quote in part: “‘…The whites always want something; they are always uneasy and restless. We do not know what they want. We do not understand them. We think they are mad.’” Jung added: “…This Indian had struck our vulnerable spot, unveiled a truth to which we are blind.” (pp.42-43.) Since that time, and following the same pattern, we have become slaves to the mechanisms and institutions of fossil fuel production and consumption, even as they have become poisonous.

In 1945, after the calamity of World War II, Jung reflected further: “Science must recognize the as yet incalculable catastrophe which its advances have brought with them. The still infantile man of today has had means of destruction put into his hands which require an immeasurably enhanced sense of responsibility, or an almost pathological anxiety, if the fatally easy abuse of their power is to be avoided.” (p.133.)

In writing this passage he broached the question: collectively, are we emotionally, psychologically, and spiritually mature enough to handle the ever-more sophisticated and therefore dangerous technology and machines we possess? The phenomenon of the North Dakota black gold rush suggests that thus far the answer is no.

We could of course continue to take refuge in our restive, raring-to-go American optimism, looking as always for another techno-growth solution. Or we could do something exceptional: given that – sadly – it’s already too late to leave this land a better land for our descendants, we could ask ourselves how we’d need to change the way we subsist in order to leave this land as unharmed as possible for them.

The answers, if they were searching and honest, would lead us to a different way of life.

Note on resources: “Oil Drilling Threatens Solitude of National Park,” Charleston Gazette, 6/23/14; Theodore Roosevelt National Park website.

SCOTT THOMPSON is a regular contributor to the Zephyr.

He lives in Beckley, WV.

To read the PDF version of this article, click here.

To comment, scroll to the bottom of the page.

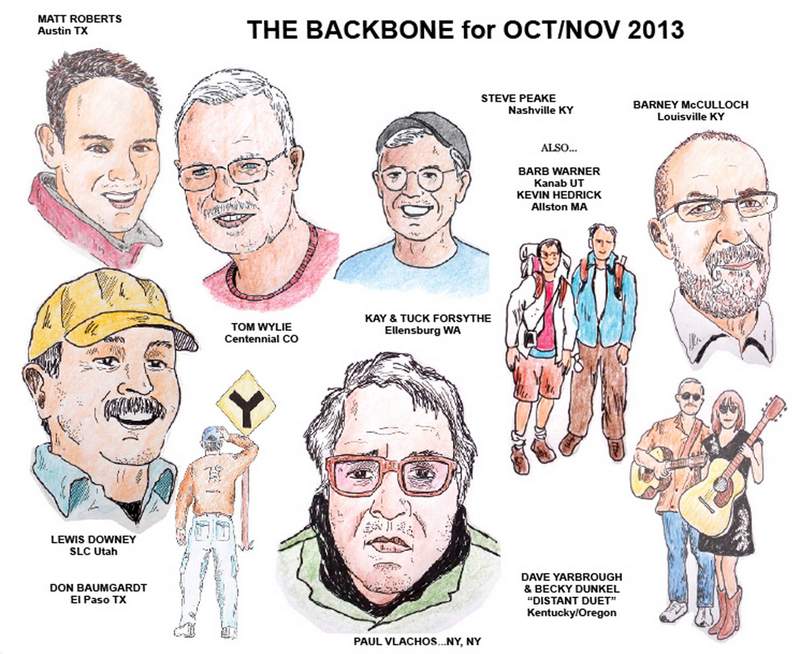

Don’t forget the Zephyr ads! All links are hot!