Sometimes a radical movement ignites a spark of passion that captures the public’s imagination. After awhile powerful people, assuming they have some foresight, come to recognize that in order to protect themselves the group must be granted a bona fide role in society. Indeed, such a maneuver often confers a bonus beyond neutralizing the movement’s threat: the group’s symbols and terminology can be turned around to support the mainstream political and economic order. While still seeming to change it. I call such a scheme change without changing.

So it is that mainstream environmentalism has thrived by focusing on environmental work that does not fundamentally threaten the mainstream political and economic order, such as preserving large tracts of wild land or fighting pollution from coal-fired power plants. And while these efforts are important, and probably necessary, they don’t effect the radical social transformations – change itself – that are essential in order to save planetary ecologies in the long run.

Another irony is that what has become vital to establishment environmentalism’s prosperity is appearing to save the environment. Yet another irony (they’re stacking up, aren’t they?) is that this appearance is maintained by the predominant belief of those within mainstream environmentalism that they are doing all they can to save the environment.

We can see how far establishment environmental groups have distanced themselves from the essential transformations – change itself – by looking at three vital issues. The first two have been well known since at least the 1960s, while the hair-raising nature of the last has became apparent to the best climate scientists in the last 5-7 years.The first issue: significantly reducing the human population. Let’s initially draw from two Elders of the environmental movement, Edward Abbey and Gary Snyder, because they wrote about the real thing.

Abbey’s comments, vintage 1967, crackle with energy. Bear in mind that the U.S. population at the time was 200,700,000, as compared to today’s 312,600,000: “It will be objected that a constantly increasing population makes resistance and conservation a hopeless battle. This is true. Unless a way is found to stabilize the nation’s [existing] population, the parks cannot be saved. Or anything else worth a damn. Wilderness preservation, like a hundred other good causes, will be forgotten under the overwhelming pressure of a struggle for mere survival and sanity in a completely urbanized, ever more crowded environment. For my own part I would rather take my chances in a thermonuclear war than live in such a world.” (Desert Solitaire, Touchstone version, p.52.) In 1969 Gary Snyder published his seminal “Four Changes,” a twelve page article that crystallized environmental priorities from a deep ecology perspective. While he wrote with a cooler hand than Cactus Ed, he was even more pointed: “There are now too many human beings, and the problem is growing rapidly worse. It is potentially disastrous not only for the human race but for most other life forms…The goal would be half of the present world population or less…The long-range answer is a steady low birthrate…the measure of ‘optimum population’ should be based on what is best for the total ecological health of the region, including its wildlife populations.” (A Place in Space, pp. 32-34.)

In 1969 Gary Snyder published his seminal “Four Changes,” a twelve page article that crystallized environmental priorities from a deep ecology perspective. While he wrote with a cooler hand than Cactus Ed, he was even more pointed: “There are now too many human beings, and the problem is growing rapidly worse. It is potentially disastrous not only for the human race but for most other life forms…The goal would be half of the present world population or less…The long-range answer is a steady low birthrate…the measure of ‘optimum population’ should be based on what is best for the total ecological health of the region, including its wildlife populations.” (A Place in Space, pp. 32-34.)

When he wrote “Four Changes” the world population was 3,631,000,000. Just recently it topped 7 billion. Snyder’s goal was 1,816,000,000 or less.Today, in spite of dropping birth rates in many places, human overpopulation remains an intense, unresolved predicament. Even if it should somehow “stabilize” at 10 billion at mid-century, as certain experts glibly predict, just think: how are that many people going to survive with a meaningful lifestyle on a planet with an increasingly unstable and therefore unpredictable climate, without completely destroying essential biodiversity and therefore themselves?

The assumption that the global population will peak at the predicted numbers and that this will somehow contribute to social stability is a pipe dream, concocted by people who find the truth either too financially expensive or too emotionally painful to bear. It’s also textbook change without changing.

If this seems unfair, consider what the classic book The Limits to Growth, first published in 1972, had to say about the matter: “The unspoken assumption behind all of the model runs we have presented in this chapter [on technology and the limits to growth] is that population and capital growth should be allowed to continue until they reach some ‘natural’ limit. This assumption also appears to be a basic part of the human value system currently operational in the real world. Whenever we incorporate this value into the model, the result is that the growing system rises above its ultimate limit and then collapses…Given that first assumption, that population and capital growth should not be deliberately limited but should be left to ‘seek their own levels,’ we have not been able to find a set of policies that avoids the collapse mode of behavior.” (Authors Donella Meadows, Dennis Meadows, Jorgen Randers, and William Behrens III; pp. 142-143.)

Stanford biologists Paul and Anne Ehrlich and their colleague Gretchen Daily have estimated that the optimal long-term global population for a sustainable civilization on our planet is about 2 billion people. That’s what the population was in 1930. (See their 2004 book, One With Nineveh, pp. 184-185.) Richard Heinberg, in his 2003 book, The Party’s Over, cited a study by Russell Hopfenberg and David Pimentel that made the same estimate. (p. 226.)

So: ask yourself if the establishment environmental organizations on your plate advocate significantly reducing global population. Another way this can be phrased is not overpopulating ecosystems beyond their carrying capacity. Check this out on their websites or when you get letters from them seeking donations.

Bet you’ll find that almost none of them do. Second issue: repudiating exponential economic growth. Here is Gary Snyder in “Four Changes:” “To grossly use more than you need, to destroy, is biologically unsound…humanity has become a locustlike blight on the planet that will leave a bare cupboard for its own children – all the while living a kind of addict’s dream of affluence, comfort, eternal progress, using the great achievements of science to produce software and swill…a continually ‘growing economy’ is no longer healthy, but a cancer…Economics must be seen as a small subbranch of ecology…” (pp. 38-39).

Second issue: repudiating exponential economic growth. Here is Gary Snyder in “Four Changes:” “To grossly use more than you need, to destroy, is biologically unsound…humanity has become a locustlike blight on the planet that will leave a bare cupboard for its own children – all the while living a kind of addict’s dream of affluence, comfort, eternal progress, using the great achievements of science to produce software and swill…a continually ‘growing economy’ is no longer healthy, but a cancer…Economics must be seen as a small subbranch of ecology…” (pp. 38-39).

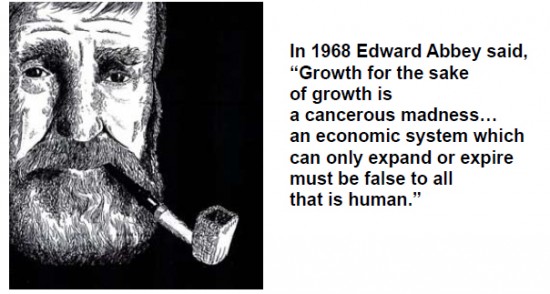

In 1967 Edward Abbey said, “Growth for the sake of growth is a cancerous madness…an economic system which can only expand or expire must be false to all that is human.” (Desert Solitaire, p. 127.) In 1982 he added: “We hear the demand by conventional economists for increased ‘productivity’…Productivity of what? For whose benefit? To what end? By what means and at what cost? Those questions are not considered. We are belabored by the insistence on the part of our politicians, businessmen and military leaders, and the claque of scriveners who serve them, that ‘growth’ and ‘power’ are intrinsic goods…As if gigantism were an end in itself.” (The Best of Edward Abbey, p. 298.)

James Gustave Speth, a professor at Vermont Law School, arrived at similar conclusions in his 2008 book, The Bridge at the Edge of the World: “Right now, one can only conclude that growth is the enemy of environment. Economy and environment remain in collision…Capitalism as we know it today is incapable of sustaining the environment.” (pp.57, 63.)

Among other things, he found destructive correlations between exponential economic growth on the one hand and increases in environmental impacts on the other, and between increasing incomes on the one hand and many negative environmental impacts on the other. (pp. 51-52, 56-57.) The pattern is simple: the more the economic output grows, the more damage relevant ecologies suffer.

He is also skeptical that reducing greenhouse gas emissions and continued economic growth are compatible processes: “In the carbon dioxide example, almost half the required rate of [technological] change is needed simply to compensate for the effects of economic growth…Perhaps it can be done. I am doubtful…” (p.114).

And he did contend that markets could be effective, at least in theory, if prices included environmental costs, which they now do not. This phenomenon is known as “market failure.” But Washington lobbyists and the government that works for them have been unwilling to make this happen, and that phenomenon is known as “political failure.” (pp. 52-54.) The trouble is that way too many powerful people have way too much money invested in keeping these failures going.

So: do the mainstream environmental organizations you’re interested in openly advocate on their websites either for scrapping growth economic models in favor of no-growth models (for example, Daly and Farley, Ecological Economics) or at a minimum insisting that all environmental costs without exception be included in market prices?

The best bet is that they’re either silent or waffling on that one.

Third issue: reducing atmospheric C02 to 350 parts per million or less FAST (the current level is over 396 ppm and rising by about 2 ppm each year).

By late 2005, NASA scientist James Hansen was openly talking about recent paleoclimate research showing that the planet is perilously close to global warming “tipping points.” Meaning that once the oceans and atmosphere heat up beyond a critical point amplifying feedbacks, including most prominently the uncontrolled melting of massive ice sheets, will take the process of global warming out of humanity’s hands. The results will be catastrophic sea level rises, massive acceleration of species extinctions due to “unnaturally rapid shifting of climatic zones,” hellaciously destructive storms from an increasingly unstable climate (we’re already beginning to get these), and an epidemic of famines from droughts, floods, and the melting of glaciers that feed major rivers. Plus other ugly surprises.

Every mainstream environmentalist not high on cough syrup knows this much. The sticking point is that in late 2007 Hansen and his colleagues determined that the safe level of atmospheric C02 is actually 350 ppm or less; that we are dangerously close to the tipping points right now. Up until then it was thought that some additional warming was safe. Another 1.2 degrees C or maybe 0.7 degrees C. In other words, it was thought that there was leeway for at least a modified version of business as usual.

Every mainstream environmentalist not high on cough syrup knows this much. The sticking point is that in late 2007 Hansen and his colleagues determined that the safe level of atmospheric C02 is actually 350 ppm or less; that we are dangerously close to the tipping points right now. Up until then it was thought that some additional warming was safe. Another 1.2 degrees C or maybe 0.7 degrees C. In other words, it was thought that there was leeway for at least a modified version of business as usual.

For more change without changing.And indeed, governments in developed countries have largely ignored what Hansen and his colleagues said, opting for business as usual. B-b-but gosh, with planetary disaster & all at stake, you’d think mainstream environmental groups would have jumped on board with 350 ppm. As the Dalai Lama did by letter in December, 2008.

But come to think of it, maybe the Dalai Lama has the advantage of not being dependent on wealthy donors, at least when it comes to environmental matters (I don’t know where the Tibetan government-in-exile gets its funding). Or maybe His Holiness doesn’t care what his donors (if any) think about 350 ppm. Either way, good for him.So: see if the major environmental organizations you’re aware of have caught up with the Dalai Lama. Look on their websites to see if they’ve endorsed 350 ppm.

Unless one of them is 350.org, I’ll betcha they haven’t.

A solid indication of what’s behind change without changing in big time environmentalism can be found in Jim Stiles’ outstanding story, “The Greening of Wilderness (Part 2),” which was printed in the August/September 2008 issue of the Zephyr. He described mainstream green board members who were, let’s see, up to their arses in coal or nuclear, or backing an airline that massively farts C02, or who have been convicted of securities fraud, and so on. Not exactly behavior that is congruent with green exemplars like Rachel Carson, John Muir, Adolph Murie, or Edward Abbey. Mainstream enviros largely responded to Stiles’ story by either ignoring it or dismissing him as a “disgruntled conservationist.”

Which meant that he hit the bulls eye: more than a few of the people who donate bagfuls of money to mainstream environmental organizations or who serve on their boards are ardent fans of both market failure and political failure. That’s the point.

I can think of three motivations for their largesse to the major green groups.Speth gives us the first: “The eco-efficiency of the economy is improving…However, eco-efficiency is not improving fast enough to prevent impacts from rising…things are getting worse at a slower rate.” (The Bridge at the Edge of the World, p. 51.) The irony is that by slowing down the rate of environmental destruction, mainstream environmentalism is in fact supporting exponential economic expansion, and with it an ever-increasing population and ever-increasing C02 emissions. It has unwittingly given an unworkable system even more time to degrade ecologies and continue its relentless trajectory toward global warming tipping points. Change without changing.

Wealthy environmental donors and board members know that once recipient organizations have large operating budgets they will be exquisitely careful to not bite the big hands that feed them. And that in time they will learn to carefully avoid advocating for change itself, because that’s precisely what the bite is.

A second motivation is that green credentials are important to protecting one’s brand in the global business world these days. So there is a kind of perverse common sense operating when an environmental scoundrel shovels money into a well known green group and then participates as a board member (think of the photo ops). It reminds me of my childhood in the small town South in the 1950s and 1960s, where the local businessmen were solid financial supporters of the respected churches around town. This was a necessary step in order to bolster their business reputations. If they slipped off to the whorehouse after being seen smiling in church, their reputations as respectable businessmen were nevertheless safe. There may be a comparable process happening with green credentials today.

A third motivation for some is a sincere desire to help the environment, while avoiding any risk to their own economic interests.To wrap up now. It often happens that when we set out to solve a vitally important problem, we end up perpetuating it, in spite of our initial idealism. This is particularly sad in the case of establishment environmentalism, because there is much to respect in the people who work within it. Many of them have given up business or professional opportunities which would have made them much more money, and they carry out pragmatic tasks that matter.

Functioning as they do within the mainstream environmental box, they probably do not like the idea that on a fundamental level their work is perpetuating the system they entered the field to change. I expect they are even less fond of the thought that they are conferring green business credentials upon polluters who come to them with mixed motivations at best.

And they especially don’t appreciate Jim Stiles calling attention to the absurdity of their circumstances.

Absurdity and sincerity make strange companions within one’s psyche.

.

SCOTT THOMPSON is a regular contributor to The Zephyr. he lives in West Virginia.

To read the PDF version of this article, click here.

To comment, scroll to the bottom of the page.

Don’t forget the Zephyr ads! All links are hot!