I’ve always liked to think that I have pretty decent luck. But it turns out that everyone has good luck until, suddenly, they don’t. On April 17th, I was on a camping trip with my husband, Jim, when I received a terrifying email. The Healthcare Marketplace, which is the website of The Affordable Care Act, was informing me that our premium tax credit had been canceled. The premium tax credit had cut our monthly health insurance costs in half, and, with no explanation provided, halfway through the calendar year, it was gone.

I called into the Marketplace immediately. “Something has happened to our tax credit,” I explained, shakily, to the operator who answered my call. “I just got an email that says it’s been canceled, but I don’t know why, or how to fix it.”

“Oh,” he replied in a calm Southern drawl, “No worries. We can fix that.” I began to protest. Did he realize how scary that message had been? But he was already moving along. He retrieved my file, took me through the application, and let me know that our eligibility for the tax credit had been restored. I began to calm down. It will be nice, I thought, if this all gets figured out with one phone call. My good luck was still intact. He read out all the details of our plan, which would be exactly the same as before, and then told me he was going to submit the plan…now.

“Hmm,” he said after a moment passed. “I’m getting an error message.”

This, he told me, was not a big deal. They got error messages all the time. I should just call back in an hour and hopefully it would be fixed. Was there anything else he could do? “Yes,” I replied. “Can you tell me what happened? Why was the credit canceled?”

“Well, I don’t really know,” he said. “It could be a few things. Was there a difference between the income you reported when you applied for healthcare and the income you reported on your yearly taxes?”

“Yes,” I admitted. “We run an online newspaper and I can never predict exactly what our yearly income will be. And then, when we did our taxes, I realized that we could claim another deduction that I hadn’t included in the application, so our income ended up being even lower than I thought.”

“Well, that’s probably it,” he said.

“But surely, it’s better that I overestimated our income than underestimated?”

“You’d think.”

“And I filled out the tax forms correctly. We got the refund because we paid too much for insurance. Why would that cancel our current tax credit?”

“It just does that for some people,” he replied, which did not help at all. “Just call back in an hour and it should be fixed.”

It should be obvious by the length of this article that the error was not fixed in an hour. Nor was it fixed two days later, when I called again. Finally, on the 20th of April, I talked to a Supervisor, who was not able to fix the error, but who did send a letter to the insurance company saying they should continue to apply the tax credit. “Don’t worry if you get a really high invoice this month,” he said. “The company has 30 days to comply with this request.” He apologized more than once for the error, repeating that this was absolutely their fault and not mine. Was there anything else he could help me with?

Yes. “Why did this happen? The first operator seemed to think it was because our income was different on our taxes than it was on the application?”

“Could be,” he said.

“But I thought that’s why we filled out the form with our taxes to rectify the two numbers?”

“Yeah, sometimes they cancel the tax credit, though.”

“But that doesn’t make any sense. It turned out we were eligible for a bigger credit.”

“I know. It’s a problem. But we’re going to fix this error and your tax credit will be the same.”

“Ok,” I finally relented. “I guess I’ll just see what happens in 30 days.” He seemed relieved to finish the conversation.

Later, I searched the internet and couldn’t find a single page explaining that a tax credit could be canceled because of a disparity between the reported income and the final income reported on taxes. Multiple pages mentioned the tax form we filled out, which would charge you extra if you’d underestimated your income, or increase your refund if, like us, you’d overestimated. But not one mention of the next year’s tax credit being canceled as a result.

And, to me, this lack of an answer was the most frustrating part of the whole debacle. How was it possible that not one page, and not one phone operator—not even a supervisor—could explain why the credit was canceled?

Thirty days passed and nothing was solved with the insurance company. Everyone apologized to me. The Healthcare exchange was very sorry for the error, but insisted that the insurance company would not be able to charge more. The people at the insurance company apologized that they hadn’t gotten their numbers sorted out and asked me, kindly, to continue to wait.

The biggest impression I got from all these phone calls was that customer service training had really improved in this country. Everyone was uniformly nice—actually nice, not at all insincere—and they all expressed that they would be just as confused as I was, given the situation. And I found it impossible to be angry with any of them, because—as they told me many times—they had as little control over the situation as I did.

The lingering question was, “Where are the people who actually control anything?” I’m not sure I’ve ever encountered one. Every time I’ve applied for an insurance policy, or called about an error in a shipping order, or contested a bank fee, I’ve faced a wall of helpless employees, who can only help me or not help me based on what they’re fed by their computer. Every sentence begins, “The computer says…” and if you’re facing an issue that is outside the computer’s understanding, then you’re out of luck.

Every large business or government program faces the same issue—how to be efficient despite the size of its bureaucracy. And, unfortunately, it seems the only way to make a bureaucracy efficient is to make it unresponsive to any complications from the confused citizen or customer. If the kind southern-accented call operator can actually make changes to help the people who call him, then he can throw a wrench into the smooth operations of the whole organization. No modern business would allow that—not in this world where efficiency and productivity are fetishized above all else.

So all the control is centralized beyond the reach of any citizen seeking help. Most often, to avoid any inefficiency at all, the control is centralized within a computer, an algorithm, which is unhampered by any personal sympathies or susceptibility to argument. And yes, the computer will probably make fewer errors overall. But when the computer does have an error, God help you. A person might make more mistakes, but at least those mistakes can be easily corrected by another person. A person can listen to a full complicated explanation, and figure out how to help. A computer can only take in the information it’s been programmed to understand, and can only spit out answers to questions it’s been programmed to answer. Just try to put “It’s more complicated than that” into a computerized form and see how well you fare.

And, honestly, I think these organizations know that most people will get frustrated and give up before they get any help.

I kept wondering about that, when I was on hold with the various operators at the healthcare exchange and the insurance company. I wondered how many people would be willing or able to keep on calling, keep insisting on updates to the progress of their case. This isn’t really something to brag about, but I am more comfortable than most when it comes to making official phone calls. I am patient, and can generally pick up the key words to remember, find the right department to talk to, and ask questions until I feel that I understand the situation. Mostly, I’m good at staying calm and forcing the person to talk to me until something is fixed. This is not a skill that I enjoy needing, but I am glad when I can get messy situations sorted out.

It frustrates me to think of the numbers of people who are too overwhelmed or confused to fight back when they are screwed over by a business or organization. You know that businesses depend on most people to give up. When they say you owe them money, who has the time or confidence to argue? I can’t be the only person who’s received a message telling them that their tax credit was arbitrarily canceled, and that their premiums would skyrocket as a result. How many other people just accepted that fate? How many people just paid the incorrect premium when their next bill arrived?

The 30-day deadline for my case being fixed with the insurance company has already come and gone. And, even when the the company agrees to continue the correct premium, (which had better be soon,) that original computer error that stymied my application will probably still be there. And so will the feeling of powerlessness that comes over me when I think about the whole situation.

This is what modern life has to offer, it seems. You just have to hope that you never fall outside the algorithm; you have to cross your fingers and hope to avoid any errors. You have to pray for good luck as you interact with a thousand different forms and applications, some of which may literally decide your life and death, and you have to hope you never hear the words:

“Sorry. The computer says no.”

Tonya Stiles is Co-Publisher of the Canyon Country Zephyr.

To read the PDF version of this article, click here.

To comment, scroll to the bottom of the page.

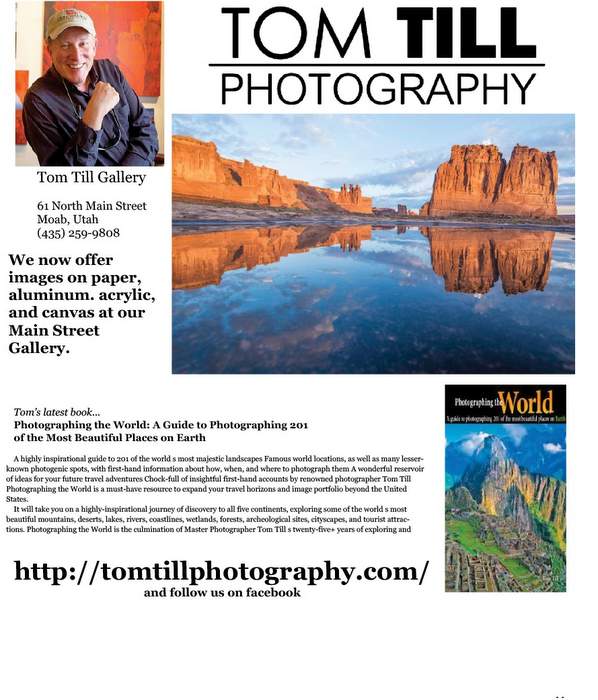

Don’t forget the Zephyr ads! All links are hot!

I think corporations are in cahoots with the pharmaceutical companies to create frustrations like Tonya’s so as to sell more blood pressure medicines, It sure makes my own B.P. go up!

Coincidentally, I read this excerpt from a Noam Chomsky talk (on the deterioration of US universities under the corporate model) the same day I read your essay, Tonya:

“[I]t’s a standard feature of a business-run society to transfer costs to the people. In fact, economists tacitly cooperate in this. So, for example, suppose you find a mistake in your checking account and you call the bank to try to fix it. Well, you know what happens. You call them up, and you get a recorded message saying “We love you, here’s a menu.” Maybe the menu has what you’re looking for, maybe it doesn’t. If you happen to find the right option, you listen to some music, and every once and a while a voice comes in and says “Please stand by, we really appreciate your business,” and so on.

“Finally, after some period of time, you may get a human being, who you can ask a short question to. That’s what economists call “efficiency.” By economic measures, that system reduces labor costs to the bank; of course, it imposes costs on you, and those costs are multiplied by the number of users, which can be enormous — but that’s not counted as a cost in economic calculation. And if you look over the way the society works, you find this everywhere…”

I think the above comment on systematically transferring costs to the public (i.e., externalizing costs), is on point. I’m 67 and in my lifetime and have seen this happen on a variety of fronts.

Good luck in getting this solved. Maybe it’ll turn out OK.