In the annals of southern Utah history, September 17, 1946 was a day to be remembered. With proper pomp and circumstance—even the San Juan County High School Band—the Hite Ferry was dedicated. With the completion of the ferry it was now possible to travel by automobile all the way from Hanksville, across the Colorado River to White Canyon and onward to Blanding. The opening of Arth Chaffin’s  homemade ferry represented the first vehicle crossing between Greenriver, Utah (for years, the name was generally written as a single word) and Lee’s Ferry, Arizona.

homemade ferry represented the first vehicle crossing between Greenriver, Utah (for years, the name was generally written as a single word) and Lee’s Ferry, Arizona.

Pioneer riverman Harry Aleson was the first speaker of the day. Before a crowd of 400, including Bishop E.P Pectol of Torrey, southeastern Utah pioneer Zeke Johnson, Utah State Roads Commissioner K.C. Wright, and Utah Governor Herbert Maw, Aleson described the effort that had gone into making the ceremony possible.

“For years Arthur Chaffin’s ranch was unquestionably the most isolated in the United States. He lived 120 miles from the nearest railroad and his nearest neighbor downstream on the Colorado was at Lee’s Ferry, 162 miles distant. The next neighbor on the river was the Bright Angel Trail, 251 miles away in the bottom of the Grand Canyon. His third nearest neighbor was my father’s son, who lived at MY HOME, Arizona, 442 miles away in the bottom of the mile-deep Grand Canyon.

“Arthur Chaffin’s ranch is still isolated—it is 70 miles from the nearest community—but today automobiles can reach the region, cross the river on the ferry, and continue on through Utah’s most colorful and primeval region, thanks to Governor Herbert B. Maw and the Utah State Department of Publicity.”

Hard as it is to believe today, only 50 years ago one-tenth of Utah was cut off from automobile traffic, a region of scenic wonders known to only a few prospectors, adventurers and cattlemen. After years of what historian/journalist Barbara Ekker described as “construction work, sleepless nights, borrowed equipment, begged funds and sheer hard work,” Chaffin managed to almost single-handedly improve the road from Hanksville down North Wash to Glen Canyon, thereby opening the area to vehicles and tourists.

Historical Hite

Long before that day, Hite was already a popular river ford, its gravel bottom and relatively broad banks providing the best—and, at times of high water, the only—crossing between Moab and Lee’s Ferry, a distance of 300 river miles.

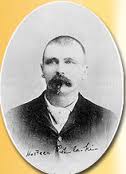

In 1883, prospector Cass Hite—a colorful, romantic figure known as Hosteen Pish-la-keen, or “Mr. Silver

Hunter” to his Navajo friends, crossed the Colorado here and carved his name on a nearby cliff face to record his arrival. Hite’s reputation as a tough character was already widespread, and stories circulated throughout the river community that he had been a former member of Quantrill’s Civil War Raiders, or at the very least a cattle and horse thief on the run from his crimes.

In hindsight, it seems more likely that Cass Hite was simply a larger-than-life figure who enjoyed his notoriety and did nothing to discourage others from spreading his legend. Thirty-five years old when he arrived in the Colorado River country, Hite was already a veteran prospector who had roamed all over the West in search of riches. In 1879, his travels landed him in Monument Valley, where two silver hunters, Merrick and Mitchell, had recently been killed while seeking a fabled Navajo silver mine. Undaunted, Hite befriended the renowned but notoriously touchy Navajo chief Hoskaninni.

Hite spent the next several years pressing Hoskaninni to reveal the location of the mine. Hoskaninni, who had defied the government’s attempts to force his people into exile had, in 1863, led a small band of followers and relatives into exile on rugged Navajo Mountain. Despite the almost complete absence of wild game and the constant fears of recapture, Hoskaninni refused to give in to Kit Carson and the U.S. Army. It wasn’t until the government finally allowed the Navajo to return home from New Mexico’s Bosque Redondo in 1868 that Hoskaninni and his followers finally left their refuge.

So it’s not terribly surprising that Hite was unsuccessful in attempting to pry the secret from his friend. Hoskaninni undoubtedly understood what would happen to his people if prospectors began flooding into the country. He also had good reason to fear what his fellow Navajos would do to him if he spoke too freely with this obsessive character. With his recent years of furtive living undoubtedly still fresh in his memory, he strongly suggested Hite go elsewhere—in fact, he offered to show him a place where gold was deposited in abundance.

Sensing that this was the best and likely the only offer he was going to get, Hite agreed. The two left Monument Valley, forded the San Juan River, went down White Canyon past today’s Natural Bridges National Monument, and ended at the Colorado River.

“There,” Hoskaninni said, motioning toward the oxbow bend in the river below. “That’s where you’ll find your riches.”

When Cass Hite arrived on September 19, 1883, the Dandy Crossing area had a population of one, Joshua Swett, a horse thief whose activities antedated the heyday of Butch Cassidy’s Wild Bunch, who also made use of the canyon, by almost two decades. But Hite thought Swett’s illicit activities would draw too much attention to the area and perhaps bring unwanted competition from other miners, so Swett was invited to take his activities elsewhere. Such was Hite’s burgeoning reputation that Swett apparently complied with only mild protestations. Not wanting to waste materials, Hite promptly moved Swett’s small (9’x12′) cabin downriver from Tracheyte Creek and reassembled it closer to the river, where the three-building “town” of Hite would soon spring up. The notched-leg cabin remained at that site until the waters of Lake Powell inundated the site in the 1960s.

After only two years, word of Hite’s activities began to spread to the outside world, and Dandy Crossing, so known because it was a dandy place to cross the river, became the unlikely center of a mining boom. Hundreds of prospectors began seeking the fine flour gold of the Colorado River and in July, 1889 a post office was established at Hite, with John Hite, Cass’s brother, named the first postmaster, a position he held until 1914 when waning interest (and lack of success) doomed the mining boom, and the post office was shuttered. As recently as the 1950s, the stone foundation of the Hite post office was still visible.

Even while the boom was going strong, Glen Canyon and the Colorado River presented unique difficulties. The nearest town on a railroad line was Greenriver, 120 miles away, which meant that a week was required to haul equipment in with a wagon and a team of horses. The roads in and out were kidney-busters, even by the standards of the time; and capital was always in short supply.

This last point was a particular problem for Cass Hite. There was gold in the bars above the river, deposited there by ice-age gravels, but in order to wash it out, it was first necessary to construc ditches, a flume and a 50-foot-high trestle to convey water to his workings. In 1891, he formed the Good Hope Mining Company and sold stock in Denver to raise needed funds for his workings at Ticaboo Canyon. Alfred Kohler, a competing prospector who seemed to have spent most of his time loafing in Greenriver, formed his own company with a similar name, apparently hoping to fool investors. But Hite traveled to Denver and took out newspaper ads exposing the hoax, a response that infuriated Kohler.

Cass Hite had a town cabin near the Gammage Rooming House in Greenriver, and it was almost inevitable that he and Kohler would cross paths. In September, 1891, when Hite returned from Denver, he was met at the Greenriver railway station by two friends who warned him that Kohler was lying for him. Disregarding their pleas, he strolled over to the Gammage Rooming House, where Kohler, armed with a rifle, sat on the porch with two friends.

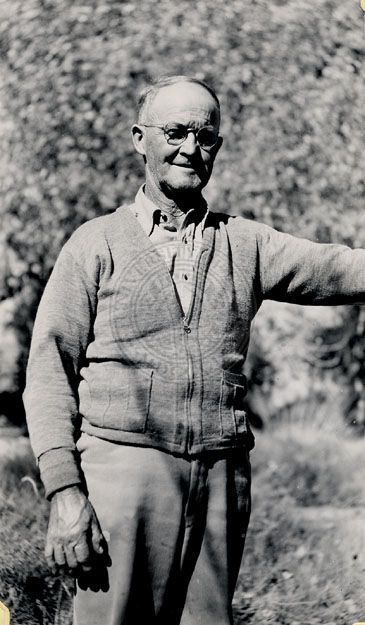

Hite and Kohler exchanged angry words, and Kohler snapped off a shot from his Winchester, narrowly missing Hite’s head. In a 1966 interview with P.T. Reilly, Arthur Chaffin, who later knew Hite well when both were on the Colorado, described the scene that ensued:

Hite’s reputation as a badman was not totally unfounded, according to Chaffin; prospectors Bill Kimball and Alonzo Turner had reported witnessing him shoot a pistol from a man’s hand, Hollywood-style, in an earlier altercation. Sitting on the porch across from Kohler, Hite’s aim was more direct. According to Chaffin, he wore a seven-inch holster with a modified .45 whose barrel had been sawed down to one inch; all Hite had to do was swing his belt holster up and fire through the bottom.

According to one account, both Hite and Kohler fired five times, but this seems unlikely given Hite’s skill as a marksman and the close quarters; more likely only two or three shots were exchanged before Kohler tumbled out of his chair mortally wounded and his two accomplices fled the scene, one of them wounded in the buttock by a hurry-up shot from Hite’s pistol. Following the shooting, Hite walked back to his cabin, where he was soon picked up by the sheriff.

Hite and his two friends were tried for murder, beginning February 27, 1892. On March 10, a hung jury was dismissed as Hite’s companions were exonerated. On October 13, Hite was re-tried in Provo before an all-Mormon jury. He was sentence to 12 years in the state penitentiary on October 15, 1892. Less than a year into his sentence, he was diagnosed with what was considered a terminal case of tuberculosis. Through the efforts of his brother, he was pardoned on November 29, 1893 by Governor Caleb W. West.

Cass Hite was transported to Hanksville by a freighter, where friends nursed him back to health. According to local stories, the formerly stocky man weighed little more than 100 pounds when he began his convalescence.

Hite never forgot the treatment he had received at the hands of the justice system, and he vowed he would remain for the rest of his life in the canyons of the Colorado. A second mining boom, coinciding roughly with the national depression of 1893, brought in yet another wave of gold hunters. Uncomfortable with the growing crowds, Hite left behind his namesake settlement and moved 14 miles downriver to Ticaboo, where he built a cabin a mile or so upriver. There he cultivated Concord grapes and watermelons, as well as other crops, on his three-acre plot.

Hite remained true to his word and never again left his ranch at Ticaboo for more than a few days. He died in 1914 and was buried near his cabi by fellow river men Bert Loper, Alonzo Turner and his brother John. By then, the second gold boom was over with only rusting mining relics, abandoned cabins and inscriptions carved by lonely prospectors on the rock walls to remind the few river visitors about what had transpired only a few years before. All of these relics were inundated by Glen Canyon dam. Today, Hite’s gravesite is under several hundred feet of water.

A modern-day pioneer

For a few years after Hite’s death, the “Dandy Crossing” environs was virtually deserted. Prospector Frank Lawler held the property for a few years, then sold it to Tom Humphries. In 1924, Humphries sold the Hite ranch to the Snow Brothers of Richfield. Oren Snow sold the property to Arthur L. Chaffin of Wayne County in 1934.

Chaffin may well have known the upper end of Glen Canyon better than any other single explorer. In 1902-03, he had operated a trading post at Camp Stone, 45 miles below Hite, where he became acquainted with Chief Hoskaninni, who was by then reputedly more than one hundred years old. During this period, Chaffin devoted much of his time to exploring slot canyons, building small boats from whatever material he found at abandoned mining sites, and trying to devise new methods of placer mining for gold.

After he left the trading post, Chaffin prospected with his brothers and the legendary William “Billy” Hay, an Irish immigrant who had reputedly run with the Wild Bunch before being afflicted with gold fever. After none of the group’s prospects panned out, he moved to Nevada and tried his luck gold mining there. In 1933, with gold prices on the rise, he returned to his beloved stone canyons and tried his hand once again at extracting the elusive Colorado River riches.

The few visitors who found themselves at this “end-of-the-road” site in those years described Hite as an “oasis in the desert.” On their comfortable ranch, Arth and his first wife, Phoebe, cultivated wine grapes, peaches, watermelons, figs, pears, almonds, peanuts, pomegranates and dates. Because Hite was located at a relatively low altitude (3300′) and sheltered by cliffs, the ranch boasted a nine-month growing season, something unheard of in that part of southern Utah.

By the mid-1940’s, Chaffin’s crazy idea of opening a tourist route into the Natural Bridges National Monument and from there onward to Monument Valley and the communities of far southeastern Utah had begun to seem just a little less delusional. His repeated visits to the Governor’s office and the Utah Department of Publicity and Industrial Development (PID), which at first seemed an exercise in futility, had begun to pay off with officials. Where formerly Hite had been considered little more than an historical footnote (the 1941 edition of the WPA-funded Utah: A Guilde to the State devoted a single dismissive paragraph to the site and its single inhabitant, Arthur Chaffin,) the state of Utah now began to take a little more active interest in “opening up” the remote and scenic White Canyon country. Chaffin had found one firm ally in Ora Bundy, then-head of the state publicity department, who allocated the initial $10,000 for the automobile route that would eventually become Utah State Highway 95.

On that September morning in 1946, with the surrounding cliffs glowing in the late-summer sun and the sounds of speakers occasionally drowned out by the calls of Chaffin’s nearby flock of peahens, the assembled dignitaries focused much of their speechmaking on Utah’s rush to attract throngs of tourists and their much-desired dollars. The comments of Arthur Crawford, of the State Commission of Publicity and Industrial Development, were typical:

“Utah with its rich lore of pioneer background is at last emerging from what President Roosevelt called the ‘horse and buggy days,’ to claim its share of tourists and of world travelers who seek out the lands of legend and of story—the quiet beauty spots of the world, the last frontiers of loneliness.”

Governor Maw was even more direct in his push for what later became known as Industrial Tourism (some things in Utah never change):

“Ever since I can remember I have heard men and women talk as we have talked here on the stand

today about the beauties of Utah, and some day it was going to be the one spot where the tourists would come from all over the world. I’ve heard them tell about the foresight of Brigham Young stopping up there at the top of Immigration (sic) Canyon and saying, ‘This is the Place,’ and the more I see, the more I am convinced that all those statements are true. But what chance has a tourist got to see any of it? Now when you come right down to it, so far as I am able to see, neither the state nor our counties nor our cities have down anything up to date to make it possible for tourists to see anything that we actually have.

“It has been necessary for the state government and the county governments and the city governments to put their road building money into highways to get from town to town. They have never had an opportunity to develop these scenic areas. The only places a tourist could really visit in Utah now if they come here are the Temple Square in Salt Lake City, which is well advertised and was built up by the church that most of us belong to; and Bryce Canyon and Zion Canyon, which were built up by the Federal Government and the Union Pacific Railroad Company. But where else can a tourist go who comes to Utah unless he gets on a horse and goes into the wilds?”

Maw’s final point is an interesting one even today, but unfortunately the country has been so transformed by his beloved improvements that few of us will have an opportunity to experience the country of southern Utah as it was only a few years ago—wild and unimproved.

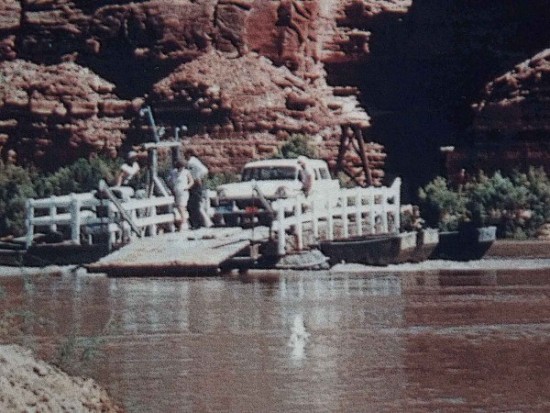

At two p.m., when the speechmakers were at last exhausted and the cold drinks dispensed, Governor Maw’s car was tugged across the river to the San Juan County side on the ferry Chaffin had constructed from the engine and chassis of a Model A Ford, as well as a wooden platform and a steel guide cable. On the return trip, a “wedding ceremony” was conducted with Chaffin, Zeke Johnson and E.P. Pectol pledging their continued cooperation in pursuit of “further development of roads through the scenic wonders of Utah and the building up of the glorious state of Utah.”

Today, one can only speculate about how the three would feel, now that Utah has been “built up” beyond their wildest dreams.

Chaffin sold his ferry in 1956, disgusted by the Bureau of Reclamation’s plan to build a giant reservoir and flood out his holdings. In 1965, he filed suit against the federal government, which had taken several of his patented claims in Glen Canyon under the law of Eminent Domain. On January 7, 1966, a jury awarded Arthur and Della Chaffin $8,000 recompensation for their lost holdings on Good Hope Bar—about four times what the government had initially offered. With court costs, however, the settlement was eaten up, and the Chaffins were, by all accounts, disgusted with their treatment at the hands of the justice system.

The Chaffin Ferry, which for 18 years had capably provided vehicle transportation at Hite, made its last official run on June 5, 1964. Four days earlier, the elevation at Lake Powell had stood at 3435.8 feet. The reservoir (it’s not a lake and should never be referred to as such, except when absolutely necessary) had been rising between 2 and 3.5 feet per day during the first week in June. The elevation at the Hite Ferry was 3447 feet. According to the official Bureau of Reclamation report, “The still water of Lake Powell is expected to reach Hite Ferry sometime after the fifth of June.”

Today, the ferry site lies under 250 feet of stagnant water.

The parallels between Arthur Chaffin and Cass Hite are fascinating. Both men worked to develop the country they loved and then found themselves displaced by growing crowds. Both were described as outgoing and generous with close friends, but retiring and somewhat shy in public. Both were, at heart, loners who preferred solitary pursuits in the canyons of the Colorado River to the company of strangers. Both considered themselves victims of the legal system and came to distrust lawyers and courts. Both saw their dreams disappear; Hite never fully recovered from his debilitating bout with tuberculosis, and Chaffin watched with increasing apprehension as the river he had loved and dreamed of sharing with fellow desert rats disappeared beneath the waters of Powell Reservoir.

But at one time, both men found happiness at the Dandy Crossing on the Colorado.

Barry Scholl is the editor of Salt Lake City Magazine.

To read the PDF version of this article, click here.

To comment, scroll to the bottom of the page.

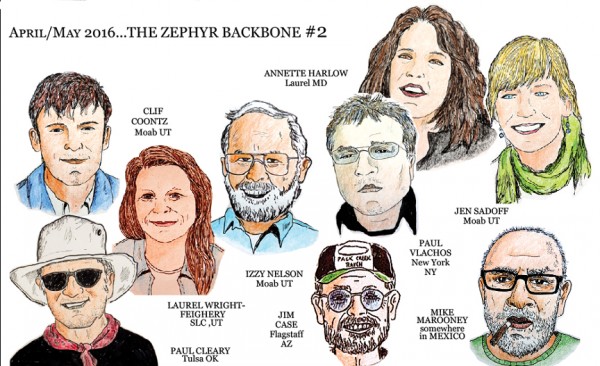

Don’t forget the Zephyr ads! All links are hot!

Great article! Arth’s grandson, Will Barclay, was a close friend of mine. He lives in Arth’s old Teasdale home. Spent many a night listening to Arth and Cass Hite stories in that house.

Interesting story, and top shelf writing skills. thank you.

Great article about “Uncle Art”. There was a lot I did not know about him. One thing it failed to talk about was how he was credited with discovering Goblin Valley (which is amazing). Uncle Art was my Grandfather’s (Faun Chaffin) uncle. I was about 5 when he passed away. I just got back from taking my son (next generation of Chaffin’s) and his scout troop to Goblin Valley and thought I would look up more about him and ran across your article. Great job thank you 🙂

I rode the Hite Ferry in June 1962. A fellow named Todd operated it then. The road to Hanksville then was really rough.

what is really sad is to read about the dreams of these hard workers being drowned almost by the very people who wanted crowds to come to Utah! Imagine the work they did, planting the poplars, other trees to beat fruit, and gardens rich with produce!! These bygone heroes get lost in the shuffle of present day life and it’s quite wonderful that you’re shedding some daylight on their efforts and dreams.

We took our grandkids and great grandkids to see the Goblin area which is phenomenal—only to read a few months later where some boys ,, Utahns I think, pushed many of the formations over! Where were their folks??

Very informative and very valuable, in regards to history on the Colorado Plateau. Thank you!