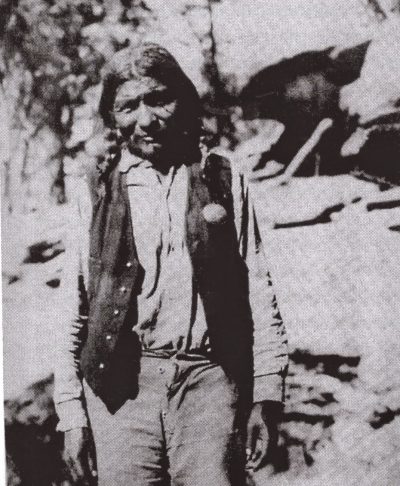

In 1923, the increasing presence of Euro-American settlers in territory formerly occupied by Ute and Paiute Indians led to what was probably the last armed conflict between whites and Indians in the United States. And the man for whom the altercation was named has become synonymous either with the Indians’ fierce resistance or with the settlers determination to resolve the issue of who owned the land.

In the estimation of San Juan County settlers, Posey was a long-time troublemaker, a renegade who terrorized isolated ranches, refused to recognize ranges the Mormons considered their own, and (perhaps most damning) galloped about the increasingly civilized environs of Bluff, Blanding, and Monticello on horseback at the front of a band of similarly-minded Indian brigands. In the minds of his followers, and some white sympathizers, though, he was a gallant leader who refused to be cowed by land-grabbing settlers.

Given the ever-growing pressure exerted on the arid range, conflict of one sort or another seemed inevitable; Mormon ranchers charged that the local Utes (Posey was a Paiute who had married into a Ute family) grazed their stock on white-held ranges, stole livestock, and on the whole refused to act like “good Indians.” The Paiutes countered that the whites’ stock-growing practices were destroying valuable plants and wildlife, and that an ever-increasing population of newcomers was encroaching on traditional Indian lands.

And so we have all the elements of a tragic powder charge ready to go off: reciprocal cultural misunderstandings, proliferating herds of sheep and cattle in an area that ecologically and geographically was unsuited for mass grazing, and a history of armed skirmishes. In 1914, a Mexican sheepherder named Juan Chacon had camped in the Montezuma Creek area with several Ute Indians including the particularly controversial Tse-Ne-Gat (a.k.a. Everett Hatch.) A few days after spending an evening with the Indians, Chacon was found dead, and witnesses claimed Tse-Ne-Gat was responsible.

Nearly a year elapsed and Tse-Ne-Gat remained at large, claiming he feared for his own life in the hands of white justice. As Robert S. McPherson has pointed out in his newly published history of San Juan County, local newspapers helped to stir things up by printing inflammatory statements such as “Hatch has a notorious reputation as a bad man,” and making the extravagant claim that he was “strongly entrenched with fifty braves who will stand by him to the last man.”

The last was enough to prompt a posse of 75 volunteers led by U.S. Marshal Aquila Nebeker to test the Indian’s resolve. In light of the newspaper’s flame-fanning, the group approached the Ute Indian camp ready for trouble. But a sentry alerted the camp and an exchange of more-or-less aimless gunfire erupted. When the smoke cleared after the first sally, one Indian and one posse member were dead. Hearing the exchange, a second group of Utes rushed upcanyon from the San Juan River and began firing at posse members from behind. At this point, the posse exercised discretion and called for a truce. They shortly departed the canyon, and the Utes, in McPherson’s words, “fled for the wide open spaces.”

The village of Bluff, which shortly before had served as the model for the violence-wracked town of Cottonwoods in Zane Grey’s fanciful Riders of the Purple Sage, now took on that quality for real. A confusing melange of state officials, Indian agents, and representatives of the military descended upon the pastoral settlement on the banks of the San Juan River. One contemporary newspaper reported that Brigadier General Scott was enroute to attempt to forge a peaceful settlement with the “recalcitrant Piute Indians.” Within two weeks, Scott had met with the 23 Indians and promised them protection from the incipient mob. The four most likely suspects, Polk, Posey, Posey’s Boy, and Tse-Ne-Gat, were transported to Salt Lake and questioned. The first three were soon released; the latter was taken to Denver for trial and acquitted of the murder charge. Needless to say, settlers in Grand and San Juan counties were not overjoyed with this turn of events.

This was not the first conflict between the races, now would it be the last. Relatively minor altercations were reported in 1919, 1921, and most famously, 1923. But the event which precipitated the so-called “Posey War” was comparatively minor. Two Ute teenagers were on trial for robbing a sheep camp,

stealing a calf, and burning a bridge. They were convicted and found guilty of theft. While being held in the basement of the sheriff’s home, one of them grabbed a gun and both escaped. The two fled to the Blanding courthouse grounds where Posey and a group of his followers anxiously awaited the outcome of the trial. The combined bunch fled town with the sheriff and a quickly assembled posse pursuing in automobiles.

By this point, settlers were out of patience. Posey, in particular, was a sore point. For years, local and regional newspapers had reported that he was guilty of crimes ranging from killing his own brother to personally shooting Joe Aiken, the one victim of the settler’s ill-fated attempt at a pre-emptive strike in 1915. In McPherson’s words, “[Posey] was such a colorful character that his threats, cajoling, and antics often brought a strong reactino to what would normally have been forgotten.”

So began the Posey War. Local newspapers reported that the county commissioners had written the governor requesting a plan equipped with machine guns; San Juan County Sheriff William Oliver authorized his troop of volunteer deputies to “shoot everything that looks like an Indian;” and some particularly incensed Blanding residents threatened that “this was going to be a fight to the finish.”

As was often the case, innocents bore much of the brunt of the conflict. A large group of bewildered Native Americans were held in the basement of the Blanding elementary school. When the group began to overflow those tight confines, a 100-foot-square area was fenced off into an improvised concentration camp to hold the hungry, poorly-clothed captives.

Meanwhile, other Ute and Paiute people fled for Navajo Mountain. Where half a century before this  rugged area south of the Colorado River had held refuge for Hoskannini and his band of Navajos when they were being pursued by Kit Carson and the U.S. Army, by the 1920s the improvement of transportation routes and a growing population proved that even this geographically isolated area wasn’t sufficient to provide refuge. As they fled, Posey and a few of his followers skirmished with their pursuers but were quickly subdued. Wounded in the hip during the gun battle, Posey was forced to watch as his people were returned to confinement in Blanding. He perished within a month. There were no white casualties. And so ended the Posey War. Sort of.

rugged area south of the Colorado River had held refuge for Hoskannini and his band of Navajos when they were being pursued by Kit Carson and the U.S. Army, by the 1920s the improvement of transportation routes and a growing population proved that even this geographically isolated area wasn’t sufficient to provide refuge. As they fled, Posey and a few of his followers skirmished with their pursuers but were quickly subdued. Wounded in the hip during the gun battle, Posey was forced to watch as his people were returned to confinement in Blanding. He perished within a month. There were no white casualties. And so ended the Posey War. Sort of.

Fanciful stories began to emerge, once again encouraged by the press, that Posey had been killed in a flash flood, or that he had died of natural causes. Some of his friends believed he had succumbed to poisoned flour. But today most historians believe that he died from blood poisoning caused by his gunshot wound.

Because rumors persisted that Posey was, in fact, still alive and possibly planning revenge, Marshal J. Ray Ward asked to be shown Posey’s body. A few Utes led him to the site and Ward satisfied himself that the corpse was indisputably Posey. He reinterred Posey’s body and attempted to disguise the site, but his attempts to quell the controversy were unsuccessful. Posey was dug up at least twice more by men who wanted to be photographed with his body. (A truly horrifying photo of Posey’s corpse surrounded by a group of cowboys is in the possession of the Utah State Historical Society.)

Sadly, from the Native American perspective, not much good came from this conflict. Although the persistent publicity generated by the Posey War led to public recognition of the problems of Ute and Piute Indians in the Four Corners area, the solution offered by the Department of the Interior was less than satisfactory. These groups of Indians were forced to surrender their traditional nomadic existence and settle on approximately 8,000 acres of land in Cottonwood and Allen canyon drainages in San Juan County. Meanwhile, their children were forced to submit to short haircuts and Euro-American fashions before being sent to the Indian School at Towaoc, Colorado. About the only positive result so far as the Allen Canyon Indians were concerned was that the so-called “Posey War” ended the period of armed conflicts between the indigenous people and the newcomers in San Juan County.

Barry Scholl is the editor of Salt Lake City Magazine.

To read the PDF version of this article, click here.

To comment, scroll to the bottom of the page.

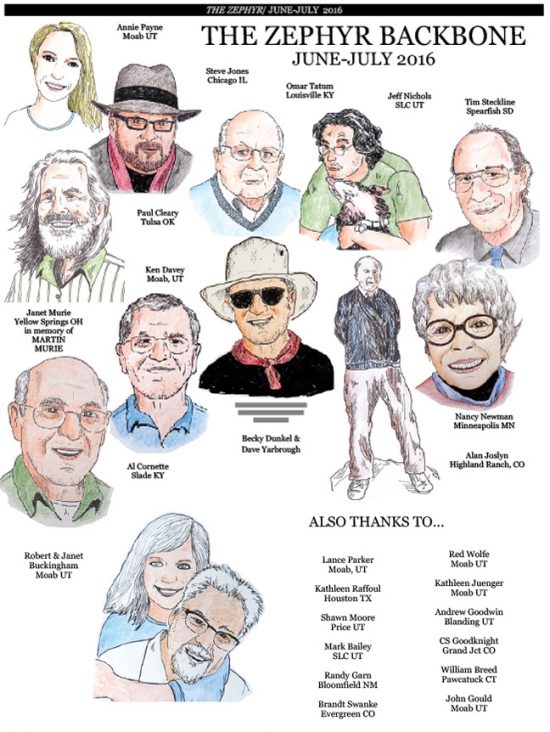

Don’t forget the Zephyr ads! All links are hot!

[…] children were shipped off to boarding schools against their will. “Posey’s War,” considered the last armed Indigenous uprising, ended a few months after the compact was signed, resulting in a large group of uninvolved, mostly […]