THANKS to Tom McCourt & the Tibbetts Family.

For years, I have been watching Moab move farther and farther away from its roots, to the point where it seems few people even know the history of the place anymore. Some of them don’t know OR care, but I think there are still many who have a respect for the past (I hope so, at least).Last winter I read Tom McCourt’s book on Bill Tibbetts and think it’s his finest work. I knew a bit about Bill, but the story was told so beautifully and I felt it was a very moving tribute, not just to Bill, but to those far off times.I see Moab as some alien world now, and I feel the most significant contribution I can make with the Zephyr these days, is to try and preserve the past in some fashion, or at least make it available for those readers who are interested. With Tom’s permission, the Canyonlands Natural History Association who published it, and with the good wishes and approval of Bill Tibbetts’ son Ray and the Tibbetts Family, we are pleased and honored to offer, over the next few months, excerpts from Tom’s excellent portrayal of ‘the Last Robbers Roost Outlaw.” JS

but the story was told so beautifully and I felt it was a very moving tribute, not just to Bill, but to those far off times.I see Moab as some alien world now, and I feel the most significant contribution I can make with the Zephyr these days, is to try and preserve the past in some fashion, or at least make it available for those readers who are interested. With Tom’s permission, the Canyonlands Natural History Association who published it, and with the good wishes and approval of Bill Tibbetts’ son Ray and the Tibbetts Family, we are pleased and honored to offer, over the next few months, excerpts from Tom’s excellent portrayal of ‘the Last Robbers Roost Outlaw.” JS

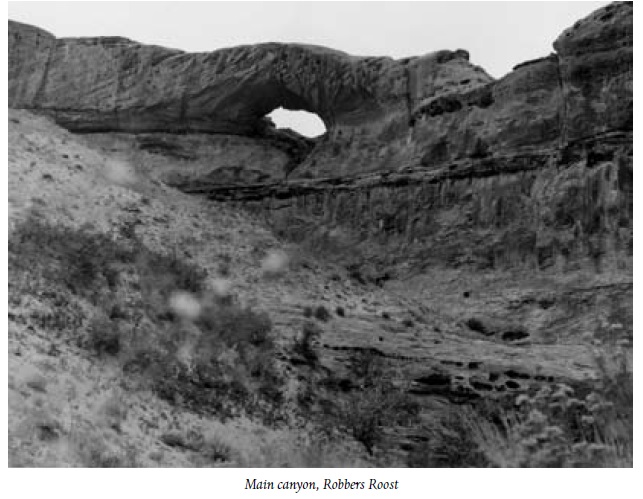

For the next six months, bill and tom hid out on the Robbers Roost. From caches near their old cowboy camps they were able to put together a decent camp outfit, and they were able to shoot deer to supplement the supplies Uncle Ephraim left for them at prearranged drop sites. With Ephraim acting as their cowboy courier, they were able to send and receive notes from family and friends and keep up on events in Moab by reading old newspapers. Overall, they fared quite well.

Sheriff Murphy did show up in Elaterite Basin to question Ephraim and look for any signs of the fugitives, but his reception was cool and he found no evidence the outlaws had been there. Things quieted down after that. The weather turned cold and posse members were volunteers who had other things to do. In addition, some people still thought the boys might have been killed in their wild escape to the river. Others suspected they had left the country. Either way, there was no sense in following a cold trail in the middle of the winter. Better to sit by the fire and wait for the fugitives to show up somewhere before resuming the chase.

However, at least one posse did attempt to venture into the Robbers Roost. One day in October, Bill spotted a string of riders coming down the Green River from the north. From a high rim he kept an eye on them as they made camp for the night on the Moab side of the river in Potato Bottom. Early the next morning, Bill and Tom were watching as the lawmen broke camp and prepared to cross the river.

The posse looked like a bunch of younger men, and they were apparently inexperienced. The outlaws watched with some amusement as the lawmen loaded their pack animals and then sucked the packsaddle cinches up as tight as they possibly could. They did the same to their saddle horses. Any old-timer could have told them to loosen the cinches. When a horse swims, he needs to fill his lungs with lots of air to keep afloat.

The fugitives watched as the lawmen dropped down into the cold and turbid waters of the Green River, where they were soon in big trouble. The heavily loaded horses couldn’t swim with their cinch straps so tight. The animals fought, floundered, and sank beneath the waves. Saddlehorses, too, thrashed violently and went under. The men struggled, screamed, and swam for their lives. Men were throwing ropes to each other and running up and down the riverbank trying to rescue horses and other men. It was a terrible thing to witness.

From their vantage point in the rimrocks across the river, the morning sun felt warm and welcome as the fugitives watched the lawmen struggling in the cold water, mud, and morning shadows of the river bottom. The far-off squeals of struggling horses and the shouts and curses of panicked men echoed in the ledges and rippled away down the canyons. As far as Bill and Tom could tell, none of the men drowned, but several of the horses were lost to the river.

The outlaws took no delight in watching the tragic scene. They had great respect for good horses and they felt bad for the inexperienced souls who had spurred them into deep water with loads too heavy and cinches too tight. Later that day, they were still watching when the wet, cold, and discouraged lawmen took the back-trail for home. Some posse members were walking and most of their packhorses and supplies were gone. The story of the misadventure was never reported in the newspaper.

The fugitives didn’t waste time while hiding on the Robbers Roost. They gathered cows. They worked the rims and river bottoms pushing steers into Elaterite Basin where they could be bunched for a cattle drive. Ephraim and young Kenny Allred worked the White Rim while Bill and Tom took care of the deep desert canyons that were a little farther removed from the prying eyes of civic-minded citizens. They were cautious and always watching their back-trail, but there was no sense to sit idle when Ephraim needed some help. What’s more, a good many of those steers belonged to Bill’s mother.

Unfortunately, most of Bill’s stock was still over on the Big Flat country where Albert Beach, John Jackson, and Owen Riordan were still on the prod. He would have to figure out how to gather them later.

By late fall, the cowboys had a herd put together and they started out of Elaterite for the railhead in the town of Green River. They pushed the steers up the North Trail and into the cedar ridges and rolling sand hills of the Robbers Roost. It took a few days to go around Barrier Canyon and bend the line of travel back north toward the Book Cliffs. They crossed the San Rafael River and went straight for the railroad tracks and holding pens at the edge of town.

With the cattle tucked safely in the railroad corrals, Bill and Tom left Green River quickly and rode forty miles to the little town of Hanksville. There were fewer lawmen around Hanksville, and no one ever asked any questions there. In that sleepy little town on the edge of the desert, an outlaw could buy a jug of moonshine and enjoy it in relative peace and security. It was the era of prohibition, and most saloons in the bigger towns served only soda pop to strangers.

A day or two later, after finishing his business in Green River, Ephraim rode to Hanksville to meet up with his drunken partners and escort them back to the safety of the Robbers Roost. His packsaddles were loaded with food and supplies.

All too soon, it seemed, it was time to do something about the cattle Bill had left over on the Big Flat. It was too risky for Bill to go there himself, so Ephraim offered to gather his steers for him. The men talked it over as they ate their evening meal in the mouth of a shallow cave, somewhere in the Robbers Roost.

“It’s purdy late in the season, but I’ll go over there and gather all I can,” Eph was saying as he huddled next to the campfire with a tin plate of beans and biscuits balanced in his lap. “You boys better stay on this side of the river. You got a few hundred head of cows over there, but probably less than a hundred and twenty steers. I think me and Kenny can handle it. We’ll push ‘em up Dubinky Wash and take ‘em to the rail yard at Thompson.”

“I sure hate to have you do the job alone,” Bill said, from the flickering shadows on the opposite side of the fire.

“It’s okay,” Eph assured him. “I sure appreciate your help on this side of the river. Laterite and the White Rim are bigger country than the Big Flat and it would have taken me all winter to gather my steers alone. And besides, the Big Flat is closer to Moab and I can get home without swimmin’ the river. That’s important to an old buck like me when the weather gets cold like this.”

Ephraim continued. “While I’m there, do you want me to push the rest of your cows off the Big Flat and put ‘em down on the White Rim and along the river bottoms with my stock? I think there’s enough grass this winter to get ‘em through all right. Maybe we can take another look at things when it warms up in the spring. What do ya say?”

“No, by Gawd” Bill growled from across the fire. “You leave my cows and young heifers overthere. I want old Albert Beach and John Jackson to see my brand once in a while. I’m not lettin’ those buzzards run me off that range. I told ‘em I was there to stay, and by damn, I’m there to stay. Especially after all the lyin’ they did to put me and Tom in jail.”

Ephraim didn’t answer for a while. He just sat and looked into the fire. Finally, he raised his eyes to look at Bill, and he said very quietly, “I’ll do what you want me to do, Bill. We’re partners in this business and I promised to help you out. But damn it, it’ll be the death of you if you keep fightin’ with those men. If you get your cows off ‘a there this whole thing just might blow over.”

“You leave my cows and heifer calves over there,” Bill said, forcefully. “My stock will still be there when the rest of those outfits are gone. Nobody is gonna run me off that range.”

Ephraim put his empty plate down on a big rock. He then sat back with his hands behind his head and looked up at the stars. A juniper limb in the fire popped and crackled, sprinkling sparks like tiny fireflies in the cool, night air. Finally he spoke, “I’ll leave in the morning and go over there and see what I can do. You boys better stay here and lay low. I’ll try to get back in six or eight weeks with supplies. Can you hang tough until them?”

“We’ll be all right,” Bill assured him. “There’s lots of deer on these cedar ridges. If things get too bad we can sneak back into Hanksville and buy a few things. Those people were purdy decent to us over there.”

Ten days later, the sun was dropping low toward the west. Afternoon shadows filled the slickrock canyons on the San Rafael Reef and patches of old snow glistened on the shady side of the pinyons. Bill and Tom were skinning a deer near the mouth of their cave when a horse and rider came into the camp. The outlaws were caught flat-footed. They didn’t see or hear him coming until he was right on top of them. Lucky for them, it was Uncle Ephraim.

Normally, ol’ Ephraim would have teased and made sarcastic remarks about how he got the drop on the unsuspecting fugitives, but this time he didn’t say anything. He just tied his horse to a pinyon tree, loosened the cinch, and went to the fire to warm himself. The boys could tell that something was bad wrong.

“What’s going on, Eph? You’ve only been gone a week or so. What’s happened?”

Eph looked at the two young men for a while without speaking. His eyes were sad, but somehow fearful, too. Finally, he spoke.

“Most of your cows are dead, Bill. I found ‘em scattered all over the range. Looks like somebody’s been shootin’ ‘em.”

A stunned silence fell over the camp. Then Bill spoke from deep down in his guts, his voice trembling with rage, “I’ll kill those sons-a-bitches!”

“Now, Bill,” Ephraim said impatiently, reaching out to touch the younger man on the shoulder. “We don’t know who did it. It could have been anybody.”

“It had to be John Jackson and old man Beach,” Bill growled.

“Not necessarily,” Eph quickly reminded. “There’s six cattle outfits on that range and it could have been any one of them. The Murphys, Taylors, Pattersons, and the Snyder-Riordan bunch are all up there, too, and they were all mad when we moved in on them.”

“Hell, it might have been all of them together,” Tom Perkins growled.

“That’s right,” Eph agreed. “It might have been all of them together. We just don’t know.”

“So, what did you do when you found them dead?” Bill asked, still shaking with rage.

“There wasn’t much I could do,” Eph confessed. “I did gather everything I could find and pushed them down to the river bottom to get them out of there. You’ve still got a hundred head or more, but there wasn’t enough steers I could find to bother taking to Thompson. I just pushed everything off the top and put ‘em down along the river. We’ll sort the steers out later. There’s probably still a few left up on the Big Flat somewhere. I didn’t have time to look everywhere.”

“Did you contact the sheriff ?” Tom asked, hopefully.

“Not yet,” Eph admitted. “I though I’d better get over here and give you boys the news. Maybe you can help scatter what I pushed off the top before they run out of feed in Anderson Bottom.”

“Hell, it wouldn’t do no good to talk to the sheriff,” Bill spat. “He’s one of the Murphys. He’d just send ol’ Deputy Beach to investigate, and we all know how that would turn out.”

“Well, like it or not, the law is about the only chance we got to make things right,” Ephraim argued. “We don’t know who did it for sure, and you can’t just go over there and pick a fight with all of those men. There’s still a warrant for your arrest and a bounty on your head. And besides, when I show the sheriff what they did to your cows up there, it’s sure to help your case in court. When the judge can see they shot your cows he’ll be more apt to believe they framed you for cattle rustlin’ last summer.”

“It doesn’t matter, cause I’m not goin’ back to jail,” Bill said forcefully. “Nobody is gonna lock me in a cage again, ever.”

“Don’t be too quick to say that,” Ephraim argued. “You might have to surrender to clear your name. You boys can’t just hide out here on the desert forever. Sooner or later you gotta go back to town to face the charges and get this mess cleaned up.”

“I’ll make a mess of old John Jackson’s face if he ever crosses my path again,” Bill promised. “I knocked the shit out of his pups and I can take the old dog, too.”

“Now, Bill,” Eph said quickly. “You boys are in enough trouble already. You just scatter those cows along the river bottom there and I’ll ride back into Moab and file a complaint with the sheriff. You fellers take the law into your own hands and you just might end up gettin’ yourselves killed. Your mothers wouldn’t like that much. You boys let me take care of it in town. Maybe I can work something out with the sheriff so you don’t have to go back to jail.”

The next morning the men split up. Eph said he couldn’t take another cold river crossing so he was going to ride thirty miles to the town of Green River and cross the river on the bridge. Bill and Tom saddled up and headed for Anderson Bottom to scatter what was left of Bill’s cows. As they left their Robbers Roost hideout, the sky was dark and gloomy. A big storm was on the way.

As they rode along, Bill asked Tom if he would scatter the cows along the river by himself. Bill said he was going to ride up on the Big Flat and look things over for himself. He said it would be better if he went alone. The two of them might attract attention.

“I know Uncle Eph wouldn’t lie to me,” Bill said. “But I gotta see it with my own eyes. If it’s really as bad as Eph says it is, I gotta do somethin’ about it. It’s free range up there on the Big Flat and I just can’t let those guys do this to me.”

“Don’t go gettin’ yourself killed,” Tom admonished. “You’re still a wanted man and they might shoot you if they see you up there nosin’ around.”

“I can take care of myself,” Bill promised.

“So what you gonna do when you find your cows all full of bullet holes up there?” Tom asked cautiously.

“If they’ve been shootin’ my cows they’ve declared war,” Bill said. “And they don’t know yet who they’re messin’ with. Old man Beach told me once that there’s more than one way to skin a cat, and he’s about to find out I’m a cat-skinnin’ fool.”

“You be careful, Bill. All the cows in the world ain’t worth gettin’ killed over.”

Bill did find his cows dead. Dozens and dozens of them. The rotting carcasses were scattered all over the Big Flat. By close examination, he found bullet holes in some of the remains and empty bullet casings on the ground near some of the others. On several of the dead cows his T-4 brand was still clearly visible, stretched tight on a partially mummified cowhide. That proud mark of his ownership seemed to scream to the heavens for justice.

A phantom rode the Big Flat country for the next several weeks. No one ever saw the phantom, but he was there, and he was busy. Cows started coming up missing. Whole herds of cows simply disappeared, and the losses were indiscriminate. All of the ranchers on the Big Flat lost livestock. Some of them lost a lot of livestock.

It was mid-winter, December and January, when the losses occurred, a time of cold weather when most cowmen were huddled in a cabin with a warm fire and a hot coffeepot. The ranchers didn’t notice their cows were disappearing for a few weeks.

When the losses were discovered and the alarm sounded, the ranchers found hundreds of cow tracks going down the Horsethief Trail to the river. There, the tracks went into the icy water and simply disappeared. Just below where the cows had entered the water, the river entered a narrow canyon with near-vertical sandstone walls. For a few miles there was no place the swimming bovines could leave the water without a desperate struggle. A few days later came reports of dozens of dead cows washed up on sandbars near the Glen Canyon settlement of Hite.

The ranchers didn’t all respond in the same way. Some started to gather their stock immediately to move them off the Big Flat and save what they could. Others loaded their Winchesters and began a deadly manhunt. All of them called in their relatives, friends, and hired hands to bunch and sort the cows that were left. Armed guards were posted and the whole country was up in arms.

But more cattle disappeared. For a few more weeks, small bunches of cows that had escaped the general roundup kept coming up missing. Tracks of a single horse and rider were found where the cows had gone over the rim and off the ledges.

Cowboys with guns hunted the phantom day and night. By day, they scoured the rims and followed horse tracks for miles through the junipers and sage. In the moonlight they rode to the tops of the hills to look for the flicker of an outlaw campfire. They never could find one. Still the phantom came like the wind, from out of nowhere, and then he was gone.

When the ranchers bunched their cattle for protection, they quickly began to run out of feed. Many hundreds of cattle were trailed off the Big Flat and taken to the lower country closer to Moab. Most were crowded onto already overstocked ranges, much to the anger and frustrations of other ranchers already running stock there. Some of the cattle were taken to pastures close to town where they could be fed with a pitchfork and properly protected. Many were eventually sold to save them from starving.

By early spring, the Big Flat country was empty. The March wind moaned over the bleached and broken bones of the Moab cattle industry.