Note:

December is here. As I write this, I’m watching snow blow over the sund,* and on the hill behind the house the powder’s already a half meter or more deep. I’m listening to Frank Sinatra sing “Have Yourself a Merry Little Christmas.” Christmas tunes are a favorite of mine, and I like the voices of my grandparents’ generation—Bing Crosby’s “White Christmas,” Nat King Cole’s impeccable version of “The Christmas Song,” and Dean Martin’s playful croon of “Marshmallow World,” to name only three. They’re nostalgic tunes. They’re supposed to be. Christmas, and December generally, is a time to sift through the old wants of memory, the old irrepressible moments of the heart when you recall the world or someone in it who has been good to you; perhaps when you sat down with your people and ate a favorite meal, or maybe when you went for a walk just outside of town but still close enough to see the Christmas lights looping over the streets and the lights inside of homes and you knew people felt warm for each other, or perhaps when you went to your grandmother’s house to celebrate Christmas Day and she built a fire for you, even though it wasn’t very cold outside, but she knew you liked a fire in the fireplace, and she understood for you—a child—that Christmas needed the smell of wood smoke as much as sweet pastries cooling in the kitchen, and you got a little older and you stood by that same grandmother and built a fire for her because she had loved you, and you had learned that love sometimes makes hard demands, and then one day, maybe another Christmas Day, that grandmother is no longer there, but a little boy asks you to build a fire for him, and you do, and maybe you tell him about your grandmother. Our worlds sometime come back to us, and at Christmas, their way back seems a little easier.

I write of a summer season in the piece that follows. It was the season I learned to fly fish, and when I fished with my Uncle Lloyd. Both of them have stayed with me for a long time now. Yet as I often do this time of year, I find myself wanting to be with them again—to walk among those same mountains, to fish the same streams, to look over and see Uncle Lloyd grinning under his thick moustache. It’s a prayer in a sense. Only god can answer.

*Sund is Norwegian for “sound” or “strait.”

RECOLLECTIONS

“And unto this he frames his songs”

-William Wordsworth

To Wear Buckskin

The first trout I ever caught was with my Uncle Lloyd. We were fishing together on a creek in southern Colorado. The creek remains one those streams that someone, anyone can find, and after a few years of fishing there, I knew the water intimately. I knew the bends that cut into the willowy banks. I knew the shoals that sluiced into deeper pools where the cutthroat trout always seemed hungry.

But I don’t refer to creeks or rivers by their names anymore. There is no creek or river that can survive its name and location being printed anywhere, in any sort of forum or magazine, book or bathroom wall (and yes, I have seen the name of certain rivers and creeks on bathroom walls). So, there was a creek in southern Colorado, and I went fishing there with my Uncle Lloyd.

The creek ran through the high country, through willow thickets and an earth divided by sloughs that flooded after each rain. That same trip was also the first time I used a fly rod. I found the rod in Uncle Lloyd’s garage, along with other pieces of his kit—his waders, a vest, a grey felt hat, and a canvas creel that smelled of fish and stale water. I proceeded to put on all of his gear. I put on the hat first. Then I put on the waders, which nearly swallowed me, and afterwards, I put on the vest and hung the creel around my neck and took up the fly rod. I then walked outside into Uncle Lloyd’s yard. That’s when I became a fly fisherman. I was ten years old.

The only reason I knew anything about the sport was because I had listened to Uncle Lloyd and my father talk about it. Dad wasn’t much of a sportsman. Lloyd, I believed, was more of a sportsman. I believed he fished more than my father. I understood, too, that he duck hunted. I was aware of his duck hunting because of an incident Dad mentioned once, one involving an icy marsh, a sudden onset of diarrhea, and a few awkward leans over the side of a boat. Sport came to me in those days as stories, not as recreation. Neither my father nor Uncle Lloyd referred to sport, least of all to fly fishing, in those reverential tropes sometimes found in books written by or for men just turning fifty. Fly fishing was a way to catch fish, using a long rod and a line thrown with the flick of a wrist. The bait, so to speak, was made of pretty feathers and yarns and tinsels tied to a curiously small hook. I could wear a floppy hat and catch fish that thrived in waters coursing through or near big mountains. And more than anything else at ten years old, I wanted to live in mountains. Uncle Lloyd lived on the edge of mountains. He and I had both come from the same coastal region of southeast Texas, and I dreamed of mountains long before I had ever set foot in them. Perhaps I had seen photographs or paintings of mountains as a very young boy, and they had enchanted me. Whatever the cause, I wanted to live in mountains. I wanted to wander in them like the mountain men I read about in books left on the bottom shelves of my elementary school library. I wanted to wear buckskin. Then I wanted to go fishing.

Uncle Lloyd

Uncle Lloyd was not an uncle in terms of blood or marriage. He was my father’s best friend. I don’t remember ever calling him anything other than Uncle Lloyd. I search my memory for the earliest moment I can place him, and I see him in a hospital room, visiting me after another surgery. I was probably seven or eight years old. I was feeling well enough that Lloyd taught me to play blackjack that day. We converted the squeaky hospital table into our card table, minus the green baize.

Lloyd had a round face and dark hair that he parted to one side in a way a friend of mine describes as an “evang-a-poof.” In Lloyd’s defense, his evang-a-poof was never crisp with hair spray, at least not when I saw him. He kept a thick, dark mustached that he trimmed at the corners of his mouth—picture Ernest Hemingway’s moustache—and he wore large, square framed glasses that had a way of slipping down the bridge of his nose. When he spoke, he stared over the top of the glasses, tilting his head forward and his chin down, almost touching that spot where our collarbones come together in the center of our chest.

Thinking of him, I realize how much of what I see of Uncle Lloyd is centered on his face. I can remember what he wore, phrases he used, how slapstick comedy made him laugh to tears, his habit of reading with one hand braced across the top of a book that he kept propped on his belly and his other hand, supported by whatever chair or couch he sat on, situated above his head and his fingers rubbing constantly together. But his face is what I see most. He was animated with his eyes and eyebrows. His looks communicated everything from you’ll be okay, kiddo to don’t be smartass. Maybe it’s our nature to remember the faces of people we have loved. To lose the faces of whom we have loved is to lose them entirely. I don’t remember anything particular Lloyd said that day, but I remember feeling better with him in the room. Lloyd had known me all of my life, yet it was beside my hospital bed, turning over cards, that I first felt close to him.

The Cutthroat

The fish was a cutthroat trout. I caught the fish in the mountain creek where Lloyd and I had gone. We made our trip maybe a week after I had discovered Lloyd’s fishing gear in his garage. The bend in the creek curled into the shape of a horseshoe, and the trout took the fly from the top of the shoe, from that place where we hold our thumb when we pitch horseshoes. I cast the fly where the creek started to curve. The current soon sucked the fly under the water, and I waited for something to happen. I didn’t know what else to do. I’m sure I tried to adopt the appearance a serious fly fisherman. I watched the water, watched the line, narrowed my eyes, stood at attention. Then I felt a fish. The take startled me, even after the fish began to tug—short, hard tugs that striped a slight amount of line from between my fingers.

I wonder if those tugs are part of why I keep fishing or, more accurately, why I desire to catch fish. Once I over-heard the wife of a famous fly shop owner brag to her customers about how she didn’t need to catch fish anymore. She fished with a fly tied to a hook that had had the bend and point filed to a nub. Probably something in me admired her practice, although as I get older, catching and keeping a few fish seems more responsible from an ecological perspective. I also like to eat fish. I eat more fish now than I ever did when I started fishing. But keeping a few fish seems the right thing to do if the river is seldom fished or the trout are over-populated. And, well, fishing is part of the old hunter-gatherer heart still ticking in some of us. Need food and too tired to chase down an antelope? Go fishing. The tug of a fish, for a fisherman, is a moment when we know that everything around us is living. The water, the trees, the rocks, the sky—they are all living, and so it was when I was a boy, with a cutthroat trout pulling against my line and rod, I felt utterly alive.

The Good World

I can see the exact curve in the horseshoe bend. I can see where the width of the creek above and below the bend starts to narrow. There are places along the creek where I can step over the water, going from bank to bank, without ever getting my feet wet. Sometimes when I move from one bank to another, stepping into tall grass, I feel the earth compress faintly under my feet. The riverbank is undercut, which in a few years will become a sign that says to me fish might live under there. I see willows up and down the valley, growing along the short meanders of the stream. I stop to look at the foothills, the aspen and spruce trees, and the long runs of slide rock climbing into the peaks of great mountains.

I can see the exact curve in the horseshoe bend. I can see where the width of the creek above and below the bend starts to narrow. There are places along the creek where I can step over the water, going from bank to bank, without ever getting my feet wet. Sometimes when I move from one bank to another, stepping into tall grass, I feel the earth compress faintly under my feet. The riverbank is undercut, which in a few years will become a sign that says to me fish might live under there. I see willows up and down the valley, growing along the short meanders of the stream. I stop to look at the foothills, the aspen and spruce trees, and the long runs of slide rock climbing into the peaks of great mountains.

That afternoon, rain moved into the valley. The creek rose, and the water churned into a discolored spate of silt and leaves. I walked slowly back to camp, though feeling eager to show Uncle Lloyd the trout I had caught. He was already in camp when I returned. In my memory I see him waiting for me. He wears his glasses, spotted with rain drops, his felt hat, a grey polo shirt, faded blue jeans and a blue wind breaker unzipped from his belly. He grins and studies me, as though he can recognize from my expression the weight of my creel. And I am carrying several fish. All of them are cutthroats. The biggest, which was the first fish, is maybe 8” long. I’m not sure why, but it was something of a custom then to display our catch in a row, arranging the fish from largest to the smallest. We did this, and Lloyd separated some of the fish that had clustered together so that we could see them better. A slight orange and buttery color tints their skin. Exquisite dark spots pepper the fish from their dorsal fins to their heads. They have bright crimson gill plates, matching the color of the neon slashes beneath their jaws. These are native fish to the Rocky Mountains, fish of absolutely clear and cold water. Uncle Lloyd looks up from our catch. He glances at me and this time smiles. He then stares over the country. Perhaps he watches the stream below us catch the rain. I believe he saw the world was good.

Damon Falke is the author of five books, including most recently Now at the Uncertain Hour. His poem Laura, or Scenes from a Common World was produced by Square Top Theatre and was an Official Selection for AVIFF Festival at CANNES.

Visit his website at https://damonfalke.com/

Click Here to Follow his Facebook Page.

To comment, scroll to the bottom of the page.

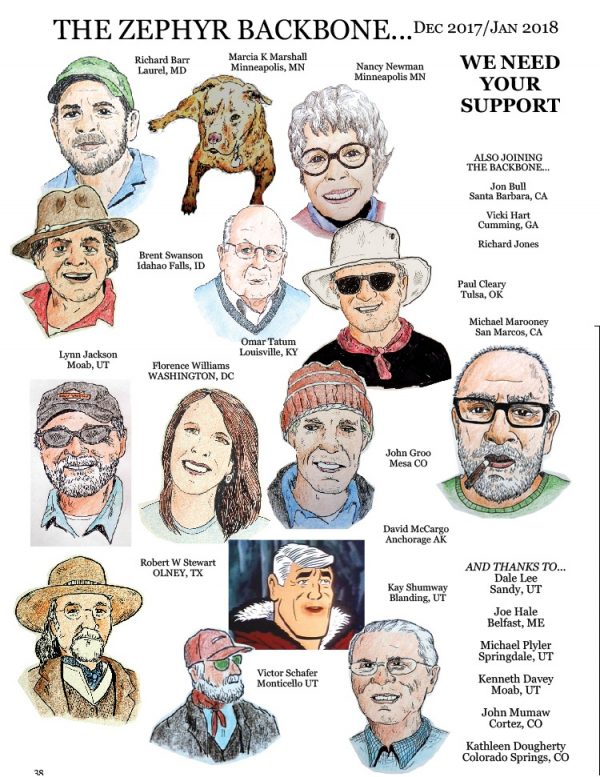

Don’t forget the Zephyr ads! All links are hot!

You capture Lloyd exactly. I don’t believe Mark & I have ever loved another as we loved Lloyd and Cheri. Your dad is Don Ray. Your mom is Judy. I believe you had a sister and at the time lived in Moab. Our son Caleb remembers you. Thank you for your postings. I look for them. We still live and farm in Dove Creek,

Cindy,

Thank you for your kind comment and memories. That time then, with Lloyd and Cheri, their kids and my family, was a very narrow window, though I spent years afterwards driving through Dove Creek and nearby communities, searching, in a sense, for those memories. I am more than pleased that something I write touches you. I’ve written more specifically about that area and Dove Creek in particular in other forums. Below I’ve attached a link to a radio program called Reflections West, in which you can hear a short prose piece and poem grounded in that time you also remember. I hope you enjoy them. Damon

http://www.reflectionswest.org/episodes/ep81_falke.php

If you should ever return, please visit us. We live five miles south of Dove Creek, just off the highway. You can ask anyone for directions. Thanks for the memories.