The main thing to remember about capitalism is that companies will always try to make you feel better about buying their product. It’s easy to be seduced by advertising—believing that buying one type of soda pop makes you a better person than buying another, buying from one clothing store makes you an environmentalist, while another means you’re fighting Cancer. We like the feeling of putting those bottles in the recycling bin. We’re good people, using our buying power to make the world a better place.

Unfortunately, we’re all pretty naïve. When we put a bottle in the recycling bin, we figure that’s the end of it—sin absolved. When we pass on the plastic bags or the plastic straws, we give ourselves a little pat on the back. When we buy the new legos made of “sustainable” plastic, we feel a little better.

And, truly, it’s the feeling better that’s the rub. Businesses learned long ago that people will pay handsomely to feel a little better about themselves. Even plastic, the very substance that now dominates our ominous headlines, was born out of that desire.

In the 1860s, billiards was the hottest game in America. An often repeated rumor is that, during the Civil War, the results of billiards tournaments were more widely reported than war news. Thanks to the Industrial Revolution, pool players had acquired chalk and leather cue tips, slate tables and rubber billiard cushions. The game, as played in the mid-1800’s, would be recognizable in any modern pool hall.

The only trouble was the billiard balls, which were still made from ivory—a material prized in those days as a luxury good. As the game expanded into small town saloons across the country, billiards companies began to fret over the continued availability of ivory—its cost and their reliance on a distant supply of tusks from elephant hunters across the ocean. Some speculated that the demand for ivory would lead to shortages, and possibly the extinction of the elephants who supplied it.

In 1863, one company, New York-based Phelan and Collender, offered a $10,000 reward to anyone who could manufacture a material to replace the ivory for their billiard balls. And so, after six years of work, inventor John Wesley Hyatt was inspired to create and submit his own ivory-hard material—a mixture of nitrocellulose, alcohol, and camphor—patented in 1869 under the name “celluloid”.

In truth, celluloid was not an appropriate material for billiards. While its appearance—hard and shiny—fairly mimicked the sheen and feel of ivory, the presence of nitrocellulose, also known as “guncotton,” was a problem. The material, highly combustible, had a tendency to explode with a loud bang when exposed to any kind of flame—say, from a lit cigar in a frontier saloon. Hyatt wrote:

In order to secure strength and beauty, only coloring pigments were added, and in the least quantity, consequently a lighted cigar applied would at once result in a serious flame, and occasionally the violent contact of the balls would produce a mild explosion like a percussion guncap. We had a letter from a billiard saloon proprietor in Colorado, mentioning this fact and saying he did not care so much about it, but that instantly every man in the room pulled his gun.

Of course, it was readily apparent that billiard balls would not be the only possible application for Hyatt’s new material, which could so easily mimic luxury materials—ivory, tortoiseshell, cattle horn. And likely its most important contribution to human history was as the material for photographic film. Advertisements for the new plastic goods made hay of celluloid’s high-class appearance, its low price, and also its role in protecting the creatures of the earth. A sales pamphlet from 1878 proclaimed:

As petroleum came to the relief of the whale, so has celluloid given the elephant, the tortoise and the coral insect a respite in their native haunts; and it will no longer be necessary to ransack the earth in pursuit of substances which are constantly growing scarcer.

Finally, a material that could be consumed with a clear conscience.

Plastic production expanded throughout the rest of the 19th and into the 20th century. In 1907, Leo Baekeland invented the first purely synthetic plastic, Bakelite, from the substance Phenol, a byproduct of coal production. Then came polystyrene, polyester, polyvinylchloride (PVC), polythene, and nylon in the late 20s and early 30s. Thanks to an increasing supply of petroleum, which is the base matter of all plastics, these synthetic materials all proved to be more lightweight and cost-efficient than the old metal and animal-based products they replaced.

World War II was the ideal proving ground for the new materials; nylon parachutes, body armor, and ropes; plexiglass aircraft windows. Scientists working on the Manhattan Project relied on a newly created material called Teflon, which resisted corrosion, to contain volatile gases. To meet all these new challenges, US plastic production surged by 300% during the war years.

The late 40s and early 50s were ready-made for the dawn of the Plastics Era. Hundreds of petrochemical factories, glutted for wartime production, had to find new domestic avenues for their products. And the American people, after surviving the double-whammy of the Great Depression and the deprivations of war rationing, were ecstatic at the prospect of buying things again.

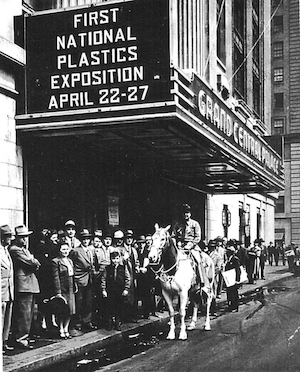

In 1946, only months after the end of the war, the first National Plastics Exposition opened its doors to a frenzied and excited crowd—desperate with what DuPont Vice President J.W. McCoy called “a great backlog of unfulfilled wants.” As Jeffery Meikle described in his book American Plastic: A Cultural History, “when the general public was first admitted, people lined up four abreast for several blocks.” Soon, the American household was inundated with plastic-based products—tupperware and polyester fabrics, latex paint and styrofoam insulation. Trashcan liners, takeout food packaging, plastic-wrapped loaves of bread and bags of produce. The new materials were cheap, easy to clean, and easy to discard.

An August 1955 headline in LIFE magazine proclaimed the celebratory era of “Throwaway Living.” A smiling family of four is pictured throwing a mass of disposable items into the air.

“The objects flying through the air,” LIFE announced, “would take 40 hours to clean, except that no housewife need bother. They are all meant to be thrown away after use.” A year earlier, in 1954, the editor of Modern Plastics had been derided for telling a Plastics conference that “the future of plastics is in the trash can”. But, by 1963, he jubilantly addressed the same conference with these words:

You are filling the trash cans, the rubbish dumps and the incinerators with literally billions of plastics bottles, plastics jugs, plastics tubes, blisters and skin packs, plastics bags and films and sheet packages. The happy day has arrived when nobody any longer considers the plastic package too good to throw away.

As economist Victor Lebow had stated in 1955, “Our enormously productive economy demands that we make consumption our way of life. We need things consumed, burned up, worn out, replaced and discarded at an ever-increasing pace.”

And so the new fanciful material that had saved millions of animals fed a culture and economy that insisted on constant disposability.

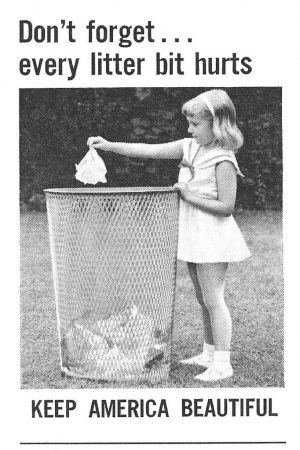

After a while, of course, all that trash piled up and became an annoyance. Even as early as the 1960s, scientists were noting the amount of plastic debris in the world’s oceans. And in 1969, the New York Times described an “Emergency in Trash Disposal” in US cities. People were becoming uncomfortable with the level of plastic waste around them. In 1973, a bill reached the floor of Congress that would have banned all non-returnable containers. The state of Hawaii attempted to ban all plastic bottles in 1977. These attempts didn’t make it very far, but it appeared the tide was turning against all that disposability. Packaging and drink manufacturers, accompanied by the oil and chemical industries, had to find a way to make their consumers feel better about using their products again.

And so were born the campaigns against litter and in favor of recycling. One anti-litter group, Keep America Beautiful, funded by corporations like Mobil Oil and Coca-Cola, ran advertisements blaming consumers for the amount of garbage in their streets. Their 1971 Earth Day campaign was taglined, “People start pollution. People can stop it.” They pushed for local communities to organize litter clean-up days and neighborhood beautification.

Even before the great proliferation of plastic bottles, in the early 70s, the Coca-Cola corporation had gotten into the business of aluminum and glass recycling in New York City. As plastic packaging took over, in the later 70s and into the 80s, plastic producers decided to push into the public’s mind the possibility of recycling those products as well. In 1998, the Council for Solid Waste Solutions, founded by the Society of the Plastics Industry, claimed that 25% of plastic bottles could be recycled by 1995. The next year, the National Polystyrene Recycling Company, founded by Amoco, Mobil Oil, and Dow Chemical, staked out the same 25% figure for food packaging—also by 1995. In 1990, the American Plastics Council announced that, by the year 2000, plastic would be “the most recycled material.”

The problem? Plastic just isn’t all that recyclable. Unlike glass or aluminum, which can be melted down and re-formed at the same consistency, plastic loses quality with each recycling. So a plastic bottle, when recycled, cannot be made into another plastic bottle. It can be re-formed into a lesser type of plastic–microfiber for clothing, plastic insulation or “wood” products for furniture, after which it won’t be recycled again. In the end, that plastic will be at the landfill or in the ocean.

And thanks to the plentiful supply of natural gas and petroleum by-products, there is no profit to be made in recycled plastic like there is in other types of recycling. In order to avoid the burden of that unprofitability, wealthier countries like the US tend to unload our recycled plastics—and particularly any plastic that has been contaminated with food products, like disposable food packaging—on countries like China, where workers labor with few safety protections and even fewer pollution controls, breaking down recycled materials into the synthetic fibers that will become clothing and carpeting, electronic components and upholstery, to be sold back to the wealthier countries. Surplus and unusable materials pile up in Chinese landfills and slip into Chinese waters. When China announced, in July of 2017, that it would ban imports of dozens of categories of foreign scrap material, including food-contaminated plastics, American recycling was hit hard. Since that announcement, countries like Vietnam, Malaysia, Indonesia and Thailand have announced their own import bans—with the result that American communities are suddenly being faced with the sheer scale and cost of the plastic waste they had previously been able to ignore.

Perhaps the greatest lie of modern plastics recycling is that, by turning a discarded plastic bottle into the small “microfibers” that form the material for upholstery, carpeting and clothing, we are somehow making good out of bad. According to the Australian Textile Exchange, “Polyester is the most widely used fibre in clothing, accounting for nearly half the world’s fibre production, or 63,000 million tonnes each year.” Of course we don’t hear the word “polyester” very often anymore because some clever advertising mind decided words like “microfiber,” “fleece” or “vegan” sounded more appealing to the consumptive palate. But, make no mistake, unless your clothing is 100% cotton, leather, wool or linen, it’s made from plastic. To make these microscopic fibers, chemical by-products of petroleum are exposed to high pressure until they liquify, and then are squeezed through tiny holes where they solidify into threads of fabric.

Some companies, like Patagonia, have attempted to relieve the guilt of their consumers by sourcing microfiber that has been made from recycled plastic bottles. And that sounds like a good thing, at first. Until you consider the relative ease of scooping a plastic bottle out of the ocean, compared with the impossibility of capturing the millions of microscopic clothing threads that escape into water from washing microfiber clothing—roughly 1900 fibers per garment, per wash. Either way, the material of that bottle ends up in the same place. But, as microfiber, it takes a far more insidious form.

When the “Florida Microplastic Awareness Project” took water samples from 256 sites around the state’s coastline, they found that 89% contained at least some form of plastic. 82% was microfiber plastic. According to a Guardian article on plastic pollution in the Great Lakes:

“The fibres seem to be getting stuck inside fish in ways that other microplastics aren’t. Microbeads and fragments that fish eat typically pass through their bodies and are excreted…There is also a chance that fibres are in drinking water piped from the lakes…Scientists reported last fall that two dozen varieties of German beer contained microplastics.”

A study released in October suggests that more than 50% of the world’s population could have microplastics in their digestive system, and no one yet knows what kind of impact that might be having on our health.

All of this information is becoming common knowledge and it will be interesting to watch as corporate brands try to find new ways to mollify a panicking consumer base. One trend is the growth of bioplastics. A Brazilian petrochemical firm, Braskem, has developed a technique in which they turn sugarcane mixed with genetically modified yeast into ethanol and then use the chemical by-products of the ethanol to produce a plastic that can mimic polyethylene, the material used in single-use plastics like soda pop bottles. Again, this sounds like a positive development. Last March, the Lego corporation announced they would begin producing Legos made from this new “sustainable plastic” sometime this year.

But there’s always a catch. This bioplastic is made from sugarcane, a crop that requires an extraordinary amount of water to grow—roughly nine gallons of water per teaspoon of sugar produced, according to the World Wildlife Federation. Fertilizer runoff and groundwater pollution is already a serious problem around sugarcane fields. And the crop is grown primarily in countries like Brazil where existing demand has spurred terrifying rates of deforestation. Brazil’s Atlantic Forest is now only 7% its original size. And, assuming only current rates of sugarcane consumption, nearly 50% more land will be needed to cultivate the crop by the year 2050. When one considers adding the weight of our world’s insatiable desire for plastic products to those numbers, the result can only be horrifying in the scale of its ecological destruction.

Someday we might realize that there aren’t any easy answers. Every time we try to make our current rates of consumption feel better, we only succeed in creating new problems. We created synthetic materials in order to spare the planet from our insatiable needs. Then, when those materials began to have a worse effect than the practices they’d replaced, we tried to mollify ourselves with recycling. When that proves to create even worse problems, we will create newer solutions, newer materials, and we will inevitably find that those, too, are destructive.

The trouble isn’t the material. The trouble lay, way back in the seed of all these ideas, with that insatiable need. And with our refusal to believe that every thing we take from our world must carry a cost. There is no escaping. We’re living creatures and, like all the other living creatures, we have to take things from our environment in order to live, in order to have pleasure and comfort and play. It’s only when our consumption looks to us like altruism—like patriotism, benevolence, or environmentalism—that we spread the most destructive germ. The entire machinery of modern economics seeks to hide that fact—pushing the environmental consequences of the first world’s choices onto the developing world’s shores. Meanwhile, back in the West, buyers shop happily, all of us convinced to our toes that we’re doing the right thing. Uncomfortable headlines flit by, but they pass quickly and soon some company will give us a better, more responsible option to waste away our dollars. Better living through stuff.

How nice it feels to have a clean conscience.

Tonya Stiles is Co-Publisher of the Canyon Country Zephyr.

To comment, scroll to the bottom of the page.

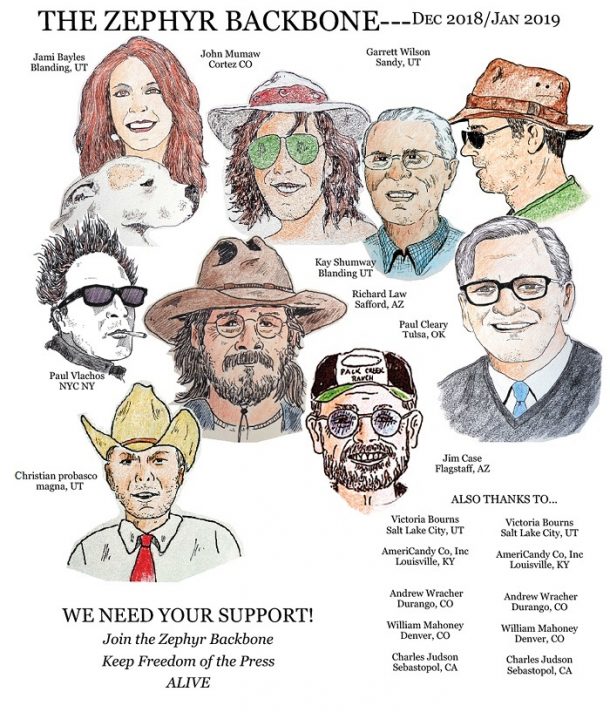

Don’t forget the Zephyr ads! All links are hot!

Great article. I did not know about the plastic microfibers from washing clothing made of plastics. Fortunately, being a redneck, the vast majority of my clothing is cotton, Levi’s, Carharts. But I do realize I still pollute in a myriad of other ways. We are a messy species. And, I get a good laugh watching these sanctimonious Moab environmentalists protest anything and everything while in the comfort of all their latest Patagonia, REI, etc new age coats, clothing and daypacks, while driving to their protest venues in their Priuses! And how good they feel when their prized little city government bans plastic shopping bags in order to save the planet! For me, as a geologist, I just take the long-term view. In a million years or less we’ll be gone, and the planet will move on to whatever it’s next state will be. Problem solved!

This blew my mind, Tonya. Nicely done.

Very nice overview, Tonya. About billiard balls: Who could’ve guessed?.

However, missing from the tick-tock was one pivotal moment in the history of commercialization of plastic. The year is 1967. After this, there was no going back. https://youtu.be/PSxihhBzCjk

Mr. McGuire: I just want to say one word to you. Just one word.

Benjamin: Yes, sir.

Mr. McGuire: Are you listening?

Benjamin: Yes, I am.

Mr. McGuire: Plastics.

Benjamin: Exactly how do you mean?

Mr. McGuire: There’s a great future in plastics. Think about it. Will you think about it?

Exploding billiard balls! Right on. National Geo did a whole feature a few issues back on the micro-plastic pollution of planet Earth. Though it’s rather alarming, I’m not sure what any of us can actually do about it. You correctly identify all of our good intentions, the behaviors that make us feel good and supposedly clear our consciences, as naive. It’s true. Recycle all you want, refrain from making additional human beings, wear only cotton, whatever…Will it even forestall the inevitable? I doubt it and the inevitable future is not a pretty picture. Dance while you still can.

Excellent article. Nano-particles from microfibers and macro-plastic degradation are already in the food-web and beginning to harm aquatic species. Also, what is happening to us when we inhale the particles? They even put plastic nano-particles in lotions and cosmetics; and these things along with the chemicals from sunscreens and lotions are measurable in aquatic food-webs. (And, wearing shade, as broad-brimmed hat and long sleeves is better than sunscreen and cooler—even in the summer—learned that growing up in Arizona.) They are now even shrink-wrapping pipe fittings, bolts, and other durable hardware! People just don’t understand that consumption is the real problem. Too many think that because something can be “recycled” it has no impact.

Years ago, when I taught high school chemistry, I used a textbook published by the American Chemical Society. The unit on organic chemistry was “Petroleum: to Build or to Burn?”. Their point was that we should not be burning fossil fuels because, as a finite resource, we should be conserving petroleum to make plastics that our technology was dependent on. Without plastics we wouldn’t have safe wiring or anything electronic. Though not mentioned at that time (>30 years ago), consuming, trashing, or down-cycling plastics is little different (maybe worse) than burning petroleum.

Regarding Big Al Jackson’s comments: I agree Moab’s plastic bag ban (like plastic “recycling”) is little more than a feel-good-pat-me-on-the-back measure than anything really productive (paper bags are bad too, in some ways worse). However, be careful about too much stereotyping Prius owners. I know a few who are sanctimonious, but not all. I have a friend in Idaho, who is almost as “redneck” as they come, bought a Prius because he needed a new car for commuting to his wildland firefighting job and wanted to save money on gas—not to make any kind of statement. He has gotten a lot of shit for it, but his 4×4 pickup he uses for camping and deer and elk hunting tends to quiet the bigoted comments. But, I agree there is plenty of ignorance on the left: for example, electric cars that are charged from the grid are essentially coal-fired and are less efficient and pollute more than my ten year old gasoline Corolla because of the multiple energy conversions needed before the rubber meets the road. As a biologist, I see the long term too: “saving the planet” isn’t the issue—the Earth has survived far worse than anything we can do and will be gone in several billion years anyway—the issues are how many other species are we going to take down and will we survive long enough to evolve or are we just another evolutionary dead-end.