Two weeks ago, many of us remembered and commemorated the 30th anniversary of Edward Abbey’s death on March 14, 1989. What would Ed think of our world in 2019? And what would the World think of him? Here are a few thoughts…JS

Three years before the publication of Edward Abbey’s masterpiece Desert Solitaire, Bob Dylan was already the iconic controversial figure that his literary cousin would eventually become. Barely in his mid-20s, Dylan was, in just a few short years, a household name around the world. In America, devoted fans and critics alike clung to every word he uttered. Every gesture was sure to have meaning. They called him brilliant, a voice for his generation, a prophet. The man born Robert Zimmerman found it all bewildering.

At a press conference in Los Angeles in 1965, Dylan faced the press. One young reporter asked about the meaning of the T-shirt he wore for an album cover. Dylan said he couldn’t recall what shirt he was referring to. Another asked if he considered himself to be predominantly a composer or a performer. Dylan said he was “a song and dance man.”

Finally, a stiff middle-aged reporter with a mellifluous voice and a need to know asked about Dylan’s role as a “protest singer.” He put it like this:

“How many people who labor in the same musical vineyard that you toil in are protest singers? That is, people who use their music and songs to protest the social state in which we live today, be it crime or war or whatever it might be.”

Dylan stared blankly at the reporter and seemed to give the matter some thought. “How many?…I think there are about 136.”

Just a trace of a smirk crossed his face. The reporter sought a better answer.

“Do you mean about 136? Or exactly 136?”

“I think it’s either 136 or 142.”

Reporters muttered and talked amongst themselves. A very few got it. Many were still seeking further clarification. Dylan smiled his cryptic smile.

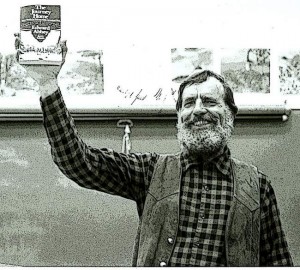

Years later, at a book signing, a fan approached Ed Abbey with her copy of Fool’s Progress. As the author scribbled his name across the title page, the woman exclaimed, “You know Mr. Abbey, I’m a novelist too!”

“Really,” Ed smiled (or was it a grimace?)

“Yes,” she boasted excitedly, “and I’ve been wanting to ask you a question. How many pages should a novel be?”

Ed stared at the woman a moment, his famous brow furrowed into a serious frown and he said without a hint of humor, “It should be 306 pages.”

The woman sighed in relief. “Thank God then…I’m almost done.”

Ed Abbey would come to know exactly how Dylan felt. His legions of devotees have been as intensely and unshakably loyal as any rock idol could hope for. I should know; I’ve been one of them—by degrees— for 35 years, though over the years, my respect for Abbey came to be centered on his humanity, flaws and all, not on an edited or distilled or politically corrected version.

But has Abbey’s myth, thirty years after his passing, become something distorted and disconnected from the real man and the life he lived? Have we selectively picked and chosen —and subsequently disregarded— his own words when they failed to affirm who we wanted him to be?

Abbey’s unflinching willingness to contradict himself confused and bewildered many of his admirers. Consequently, his readers have increasingly preferred to to edit and even sanitize their favorite author, instead of honestly weighing and scrutinizing his conflicting perspectives.

Now,

as we approach the end of the second decade of the 21st Century, the

Spirit of Abbey Lives (sort of). But can Abbey still be Abbey?

Consider this recent post by The Grand Canyon Trust. On what would have been Abbey’s 89th birthday, GCT Communications Associate Ellen Heyn wrote:

“In honor of Edward Abbey’s birthday, we’re celebrating his cult classic book The Monkey Wrench Gang—not as a guide to sabotage, but as a guide to some of the Colorado Plateau’s most spectacular places. Here we retrace the steps of George Hayduke, Seldom Seen Smith, Doc Sarvis, and Bonnie Abbzug in their crazy chase around the plateau.”

Fearful the Trust might look too radical, but still wanting to “honor” Abbey, they chose to take one of his most controversial but highly respected works and turn it into—god help us all—a travel guide. What could be more dis-honoring than that?

Still, Edward Abbey lives on via his books. He is memorialized on YouTube and honored and quoted on Facebook. His fans adore him, or the man they think he is. But is this the world and the West that Abbey cherished and loved? Is the New West compatible with his vision of wilderness and wide open spaces? Of solitude and silence?

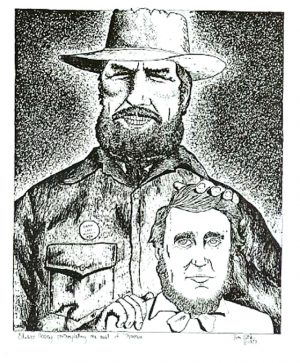

In Desert Solitaire, Abbey offered a unique reason for establishing wilderness. “We may need wilderness someday,” he proposed, “not only as a refuge from excessive industrialism but also as a refuge from authoritarian government, from political oppression. He warned that “technology adds a new dimension to the process,” and believed (then) that the wilderness would provide escape from those kinds of Big Brother controls. For Abbey, wilderness was meant to be the one vast “blank spot on the map,” as Aldo Leopold longed for.

He also wrote, “A man could be a lover and defender of the wilderness without ever in his lifetime leaving the boundaries of asphalt, powerlines, and right-angled surfaces. We need wilderness whether or not we ever set foot in it. We need a refuge even though we may never need to set foot in it.”

In 2018, he would not recognize the wilderness he sought to protect (though in his journals, in 1987, he had already complained, “Too many tourists in the backcountry now.”)

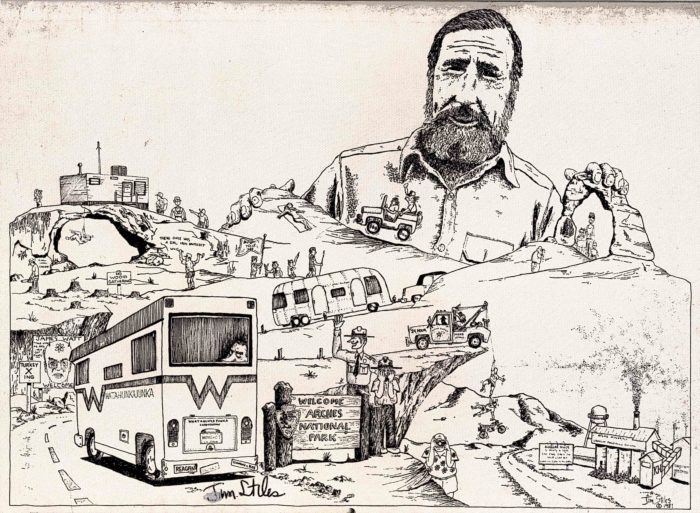

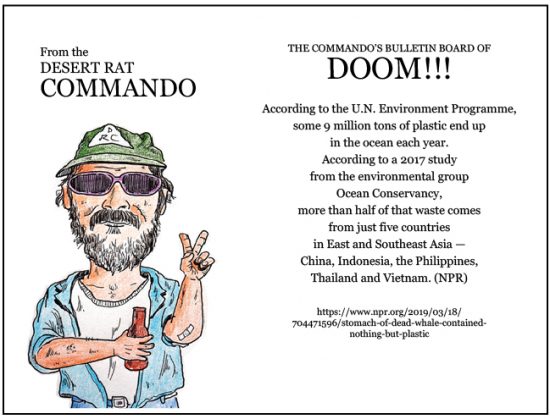

Environmental groups, once dedicated to saving the wilderness that Abbey envisioned, now look at wilderness as a commodity to be marketed. What is the economic value of wilderness? Environmentalists promote the notion of a swarming tourist economy. They’ve taken a favorite Abbey line: “The idea of wilderness needs no defense; it needs more defenders,” and turned it into a Chamber of Commerce promo….the more money that can be made from the product, the greater the chance, in their estimation, of passing wilderness legislation. Never mind what gets destroyed in the process.

Even grassroots groups, who once worked for the protection of the land and the satisfaction that they were honest participants in “the good fight,” now parse their battle cries and make a $100K a year. Their boards of directors are filled with wealthy fat cat industrialists that would have had Abbey deported if they could have found a way. Together, they support a massive recreation/amenities economy that brings millions of tourists to the once remote rural West and with it, untold quantities of money and environmental devastation.

Adrenaline junkies from the far corners of the planet descend on the canyon country to string slacklines, and rock climb and pedal extreme bikes off cliffs and BASE jump and ‘do’ the river…

Abbey used to talk about “a loveliness and quiet exultation.” Nowadays exultation is the din and roar of “Industrial Strength Recreation.” Canyon country means massive tourism promotions, shameless marketing campaigns, obscene traffic gridlock, and unspeakable mobs of insensitive ‘visitors’ to the most beautifully heartbreaking lands on Earth.

It’s the “New West,” the “faux communities” that sprout across this once empty landscape like a North Face pop-up tent, and the greed-driven promoters who seek to exploit and destroy the very qualities of the West that we all supposedly cherish, but which seem to have become so profitable.

When Abbey talked about seeking wilderness, he admonished us, “to walk, better yet crawl, on hands and knees, over the sandstone and through the thornbush and cactus. When traces of blood begin to mark your trail you’ll see something, maybe.” When he talked about riding bicycles, he imagined them as a replacement for cars, not feet. He did not envision luxury “adventure tours” and hand-held, catered/guided hikes to “remote locations,” barely a mile from their cars.

Abbey wrote, “We don’t go into the wilderness to exhibit our skills at gourmet cooking. We go into the wilderness to get away from the kind of people who think gourmet cooking is important.”

And he didn’t envision a wilderness experience that included cell phones, smart phones, GPS units, or daily uploads to Facebook (“Here’s what our sunset looked like tonight! Here in the WILDERNESS!” —–126 ‘LIKES’)

Yet, many of these recreationists convince themselves they are the latter day disciples of a man they know practically nothing about, or bother to know.

A couple years ago, an essay appeared in High Country News called, “What Would Edward Abbey Do?” The author and a group of friends had come across a huge boulder, perched on the rim of a mountain valley. Michael Branch felt an urge to knock the rock from its resting place and send it flying from its rim-side perch to the tranquil scene below. It was an absurd notion and the damage it would cause was incalculable. But one member of the group spoke up.

“Whenever I am uncertain,” replied Francois in a thick French accent so utterly authentic that it sounded hilariously fake, “I abide by this principle: WWEAD.” When he had finished pronouncing each letter with meticulous emphasis, the three of us looked at him quizzically. “What would Edward Abbey do?” he explained coolly.

“What would Edward Abbey do?” Based on that rhetorical question and, I guess, the vague recollection that Abbey claimed he rolled something into the Grand Canyon—an old tire—almost 70 years ago, the guys decided it was a good idea. Branch exclaimed, “I was Sisyphus unbound, and I had a Frenchman’s love of Cactus Ed to thank for it.”

I doubt Abbey would have felt comfortable being an accomplice from the grave, but he shouldn’t have felt responsible either for their vandalism. Clearly, they’d learned nothing at all from Cactus Ed.

What Abbey always hoped we’d take away from his writing and from his life was a sense of ourselves as individuals, as men and women who could take control of our own lives and our own destinies. Abbey spoke of a “nation of bleating sheep and braying jackasses.” He longed for a people with dignity and courage and he loathed the mindless “bleating” that he found even in his own readers.

He once said, “ If America could be, once again, a nation of self-reliant farmers, craftsmen, hunters, ranchers and artists, then the rich would have little power to dominate others. Neither to serve nor to rule. That was the American Dream.”

Most New Westerners love Ed Abbey and have no idea what that means. They’ve read all his books and they follow and “LIKE” his quotes on Facebook, but they understand far less than they realize.

A while back, I saw a string of comments about Abbey on the Facebook page devoted to his life.

A debate broke out of sorts—another one of those tedious comment threads— as to whether Abbey would have liked the internet. One man was sure he’d have nothing to do with it; another wrote, “He would have found much to admire in the expression of democracy it affords.” That was a fair point.

What Ed would have loathed is the idea that his most loyal fans might spend their days in front of a laptop computer, week after week, clicking the “like” button each time one of his EA crowd-pleaser quotes got posted, when they could be outside, chopping down a billboard or taking a good long walk, or just watching a nice sunset.

Abbey may have hoped, when he left this world, that his time and effort here might make a small difference, might alter the future for the better in some way. But probably not. More than likely, he saw all this coming, just as he predicted so much that has already, sadly, come to pass.

Abbey always admired the great poet and composer and performer, Utah Phillips. His haunting and prophetic, “The Telling Takes Me Home” predicted a future that few of us saw coming. Phillips wrote:

Come along with me to some places that I’ve been

Where people all look back and they still remember when,

And the quicksilver legends, like sunlight, turn and bend

It’s sad, but the telling takes me home.

*

Walk along some wagon road, down the iron rail,

Past the rusty Cadillacs that mark the boom town trail,

Where dreamers never win and doers never fail,

It’s sad, but the telling takes me home.

*

“I’ll sing about an emptiness the East has never known,

Where coyotes don’t pay taxes and a man can live alone.

And you’ve got to walk forever just to find a telephone.

It’s sad, but the tellin’ takes me home.”

The West was and should have always been about silence and space. Lots of it. About endless landscapes that stretch to infinity, and skies so vast and unbroken that they defied description, and moments of such incredible beauty and clarity that you thought you’d burst if you didn’t share this extraordinary moment with someone right then and there.

And what made the West so special was that you couldn’t.

The West was about remoteness and unimagined quiet and sometimes it made us crazy trying to decide if we loved it for its solitude or loathed it for its isolation. We really did have to walk forever to find a telephone.

No one can truly know the West and love the West without also hating it. But it was the West’s unforgiving nature that also made us feel stronger. We chose to live here with all its emptiness and hardship and unforgiving space. Somehow being able to survive the West, on its terms, gave us a leg up on the world.

Still the West overwhelmed us and filled us with unbridled joy and crushing loneliness, all at once. Like a bear hug from the Universe, we’d stand on the summit of a favorite peak or stretch out on our backs in the middle of a desert valley and for a moment we’d almost be giddy. This, we said, is pure unadulterated joy…

And then the silence would sweep over us and we’d search for some sign that we aren’t as insignificant as we feel, and we couldn’t. We’d look around and think—it’s so…big. And suddenly our laughter would sound like the hollow giggles of a mad man let loose in a coliseum and we’d start to cry. Because this was as good and as bad as it gets.

That is what Ed Abbey was all about. Who remembers?

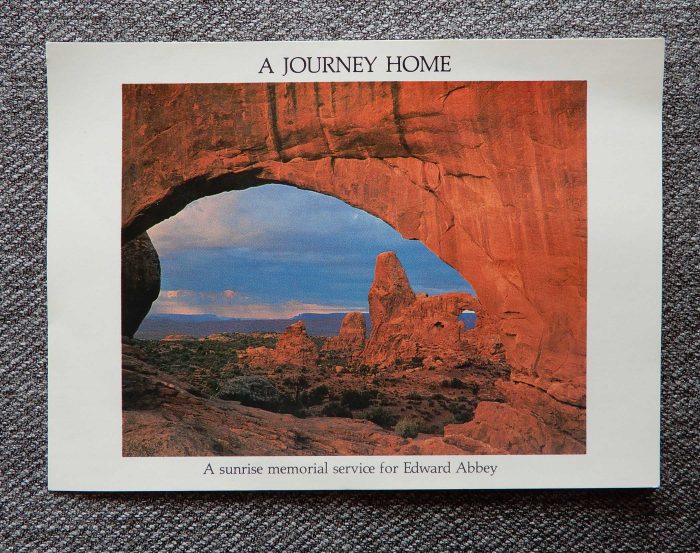

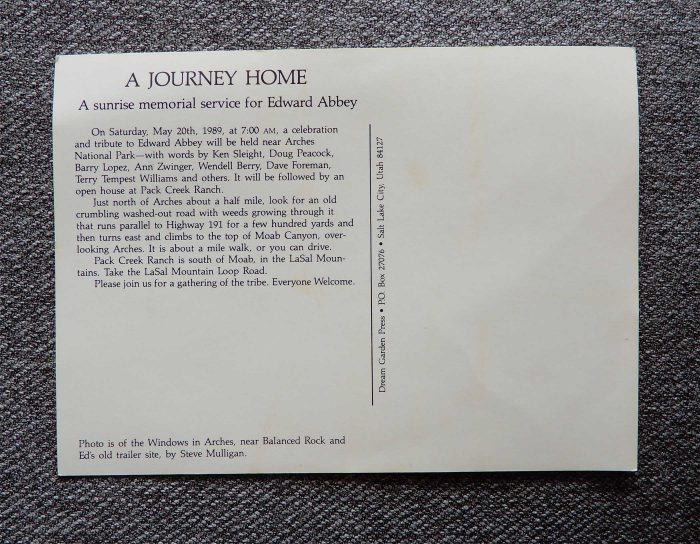

Edward Abbey died on March 14, 1989, thirty years ago.

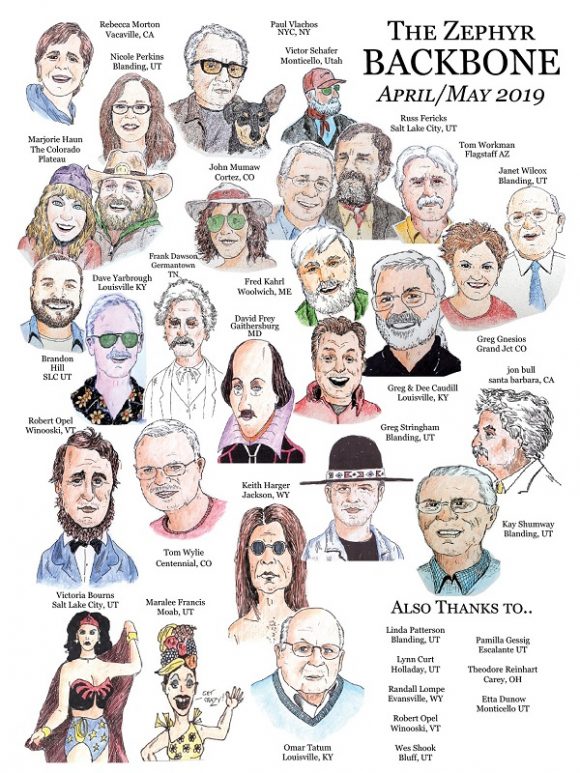

Jim Stiles is Founder and Co-Publisher of the Canyon Country Zephyr.

To comment, scroll to the bottom of the page.

Don’t forget the Zephyr ads! All links are hot!

Somewhere in the early 1970s, a friend and I toured the Moab area, camping along a creek near Newspaper Rock. We rolled out our bedrolls … no tent … upon bare ground. As I washed our dinner plates in the creek, it was pitch dark, and an elk bugled his shrill call, a sound that raked up my spine and froze me in terror. Next morning, we parked next to Newspaper Rock and “read” the pictographs, trying to interpret them. I could also hear the Ancients whispering in my ear. My friend urged me to drive his stick-shift MJ on the sandy road to the end where we hiked a while among the goblins, climbing atop one for a full-body, sun-burning love-making session.

Fast forward to 2015 and a family trip. “Our” campground is now formally designed and paved. A fence keeps visitors out of touching range from Newspaper Rock and the parking lot around it includes pit toilets. The dirt road is now paved to the end and I would never for the life of me be able find that flat-topped love nest. Gratefully, this Bookcliffs part of Canyonlands is not as crowded as Arches. Cows still graze in the ranch’s meadows. And I marvel that the Ancients’ cave dwellings and the remains of a cow camp were found for us all to enjoy. There’s still a lot of empty out there. But I wonder if I will ever again hear an elk bugle after dark, sending the call of the wild raking up my spine.

As Pogo said,”We have met the enemy and he is us.” Good job, Jim.Keep it up for as long as you can.

Since November I’ve been 2400 miles east of Flagstaff because my family needs me here. Too long. Most of it’s gone, anyway, as Abbey said. I miss it so bad it hurts. And your telling took me home, Jim. Thank you.

Ed Abbey was awesome. Read Desert Solitare, Monkey Wrench Gang, and Hayduke Lives. Love of the West came to me too late in life. Now I can only read about the beauty and wilderness.