Everybody has a plan until they get punched in the mouth.

– Mike Tyson

In modern America, local zoning has become a primary mechanism through which a wide range of hopes and fears for social and economic conditions are hashed out. In the New West, in particular, it is the oft-cited panacea to growth. Unfortunately, zoning is not remotely capable of delivering on the expectations the public projects upon it.

Let’s examine a specific example of how the process often plays out in practice in a high-growth context from the edge of Utah’s canyon country.

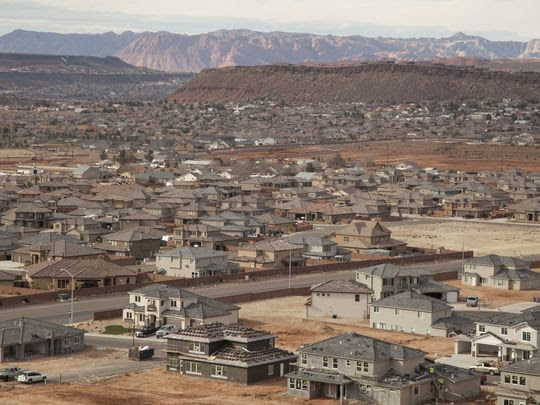

During the decade that just ended, Washington County’s population grew by an estimated 42,435 to over 180,000, which is 30% more people than lived in the county at the start of the decade. Narrowing the focus further, the area known as Little Valley has grown faster than anywhere else in greater St. George. There have been around 500 new homes built within the Desert Hills High School boundary each recent year, a number which is dominated by the growth in Little Valley. The pace of development in this part of St. George means that a large, discrete area with a full-time population similar to towns like Moab or Kanab has been built very quickly, which makes it an excellent case study for zoning realpolitik.

Like the rest of Utah’s Dixie, there wasn’t much happening in Little Valley until quite recently. In 1980, the population of Washington County was about 26,000, with St. George City accounting for about 12,000 of that total. I-15 had been completed for less than a decade and annual visitation of Zion National Park had just cracked 1,000,000. A decade plus later, by which time Zion visitation had doubled and the city’s population had roughly tripled, there was still nothing much happening in Little Valley.

Even ten years ago, by which time the population of St. George had doubled again to over 70,000, there still wasn’t much happening in this corner of town. A few suburban subdivisions — along with elementary and intermediate schools, and a large baseball and park complex — were built just before the recession, which effectively brought the edge of St. George into the northwest corner of Little Valley. Farther south and east, there were a few off-grid hobby farm subdivisions that were built before the area was annexed into the city. But mostly it was still just sunbleached desert and a few alfalfa fields.

Of course, local planning and zoning was a dynamic activity in southwest Utah throughout these decades of explosive growth, and in the go-go year of 2006 the communities of Greater St. George undertook a major regional land use planning effort called Vision Dixie. The planning process followed all the best practices, and the resulting document hit all the right notes, for smart land use and the management of growth. Among other goals, it was agreed that new development should consist of a wide range of housing types arranged in walkable, mixed-use neighborhoods in order to reduce car dependence, provide affordable housing options for the entire spectrum of residents, and maximize the preservation of sensitive and scenic features of the area.

Since it was obvious at that time that Little Valley would be one of the next major growth areas in the county, a follow-on master plan, called the Little Valley Sub Area Plan, was developed and adopted by St. George City in 2007. This second plan was essentially a site-specific application of Vision Dixie’s modest tilt toward traditional (pre-war) development principles. Specifically, the Sub Area Plan anticipated that about 55% of the new homes built in Little Valley would be detached, single-family residences and that the entire planning area would yield a gross residential density of around 3.8 homes per acre. This residential mix and concentration would result in a socioeconomically integrated neighborhood and make feasible a wide range of commercial and civic uses so that the area would become relatively walkable and multifunctional (i.e. a car trip would not be required every time a resident needed a quart of milk).

Since then, about 1,000 acres, which comprises the lion’s share of Little Valley, has been built out. However, the result looks decidedly different from what was contemplated by the Vision Dixie and the Little Valley Sub Area plans.

(Most of the undeveloped gaps you can see in the photo have been filled since the photo was snapped two years ago. The new regional airport, which is located on the other side of Crimson Ridge from Little Valley, is in the bottom right corner.)

Under the Sub Area Plan, the roughly 1,000 acres would have contained a total of around 3,800 homes. Instead, build-out will occur at around 2,000-2,200 homes. Whereas the Sub Area Plan called for 55% of the residences to be of the single family detached type, 100% actually are. This seismic shift in the residential mix has killed the feasibility of complementary civic and commercial uses beyond a few small parks and one small commercial corner.

Like similar suburban tracts everywhere, this low-density monofunctionality makes life in Little Valley completely car dependent. From the heart of Little Valley, it is three miles to the closest supermarket. (A large commercial project may eventually be developed at the intersection of 2450 South and 3000 East. If this happens, the distance to a supermarket and similar services will shrink, but the number of daily car trips made by Little Valley residents will not drop by a meaningful amount.)

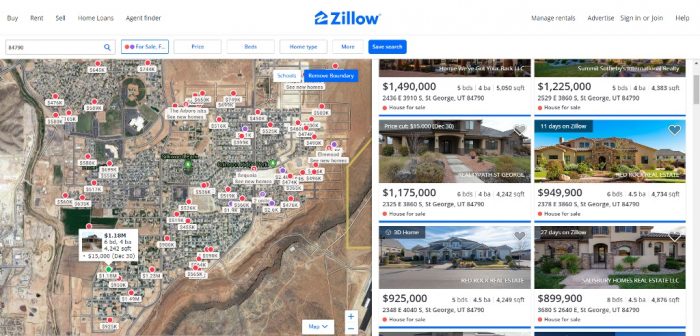

The departure from the master plan has also certainly done nothing to positively contribute to housing affordability. In a city with a median household income below $50,000, the price of a home in Little Valley starts at about $400,000 and goes up steeply from there.

A somewhat subtle effect of this instance of socioeconomic segregation is playing out in the local schools. All the area high schools that were opened prior to Desert Hills High had a good mix of neighborhoods within their boundaries. All of them included relatively poor and relatively wealthy areas; there was really no right side or wrong side of the tracks in terms of school boundaries. Compared to many cities of all sizes, it was a refreshing dynamic. This prior sort of equilibrium has changed significantly with the concentration of larger, more expensive homes within the Desert Hills boundaries and within Little Valley in particular.

A couple of other quality-of-life considerations are worth noting. A more efficient, compact development pattern like the one codified in the Sub Area Plan would have considerably reduced water usage and established the critical mass of population necessary at the neighborhood scale to support a greater mix of civic and commercial land uses. By extension, this would have resulted in more tolerable traffic conditions by reducing both the number and length of necessary car trips. The Little Valley Sub Area Plan also anticipated much more recreation and park space. In practical effect, the choice was made to privatize most recreation and leisure space (in large individual lots) rather than aggregate it and make it a shared community amenity in the form of public parks.

The public finance impact of these choices is also worth considering. The purchase of each new residential building permit in St. George requires the payment of around $21,000 in impact fees. Multiplying this figure by 2,200 homes gives you a total of $46.2 million in impact fees generated by the growth in Little Valley. That’s a lot of money, but adherence to the original Little Valley plan would have generated close to $33.6 million more from the same acreage just from the additional 1,600 homes. There would also have been a significant bump in the haul from impact fees due to the higher quantity of land used for commercial purposes under the 2007 plan.

So, in rough terms, the same land mass could have generated not roughly $48 million in impact fees but more like at least $80-$85 million to pay for things like water development, parks, public safety facilities, regional storm drain and sewer treatment facilities, etc. Put differently, the short term consequence of departing from plan is the loss to the community of a really big carrot.

And the long term consequence will be a very unpleasant encounter with the stick: roughly the same system of public works that would have been required by the Sub Area Plan now serves a vastly smaller tax base. When it comes time for the major repair or total replacement of Little Valley’s crumbling infrastructure in 30 years or so, it will be the residents of other parts of St. George bearing most of the burden. That’s a plan of public finance that works fairly well during periods of growth, but when the growth comes to an end, and eventually it always does, the resemblance of this approach to a Ponzi scheme becomes apparent.

The question begged by this narrative is this: how did such a complete departure from the master land use plan happen? The answer, really, is one application at a time.

The biggest change in direction was the first. Shortly after the Sub Area Plan was adopted, Little Valley’s largest landowner brought in a detailed development plan for the area that included a variety of housing types oriented around a village center of commercial and civic uses. Despite its consistency with the master plan, the application was denied by the city after it met fierce opposition from the hobby farmers in Little Valley with an assist from their more suburban comrades living on the edge of the planning area. (An important, technical distinction that bears noting is that the Sub Area Plan was adopted into the City’s General Plan, which does not have the controlling force of zoning. That required a separate, specific application, which was denied based on the city’s relatively broad legislative discretion.)

This denial worked as a de facto moratorium that stretched out several years. The developer went back to the drawing board and the recession happened. But people continued to move to St. George and the excess housing that was built during the bubble was gradually purchased and occupied by those new residents. Eventually, there was demand for more housing, which led to new development applications pertaining to Little Valley. One by one, each zone change application ended up looking like the suburban pattern that has ended up being built. Not because the regional planning context or what constituted “smart” land use had changed, but because it’s what could get approved.

Consider this another chapter in the complicated story about how the New West is made. The rate of growth shows no signs of slowing in this corner of canyon country. Recent studies published by the U’s Kem Gardner Policy Institute show that tourism continues to boom across the southern part of the state. In Washington County, Transient Room Tax roughly doubled during the decade of the 2010s and the annual “Leisure and Hospitality” industry is now well over $1/2 Billion in taxable sales. And, unlike much of canyon country, people are not just visiting, but are moving in droves into the southwest corner of Utah: in-migration accounted for over 33,000 of the 42,435-person change in population in the last decade.

Eventually, Greater St. George will run into hard constraints to growth, but those are further off than some may think and the demographic trends driving the growth still have a lot of life left in them. So, in the meantime, the action shifts to planning and zoning, which, writ large, is mainly an exercise in squeezing air from one part of a balloon to another. It can’t stop growth nor even “control” it in any meaningful way.

Stacy Young is a regular contributor to the Zephyr. He lives in Southwest Utah.

Author’s Note: With some frequency I see comments or criticisms that the Zephyr is too descriptive, only offering criticism of the way things are and not offering solutions or recommendations for how things could or should be. I personally think (a) in the age of hyper partisanship and the armchair quarterback, it is refreshing to read things that don’t insult my intelligence by reducing complex phenomena to fit within narrow (usually ideological) arguments, and (b) there is real value in simply documenting in real time the processes that are transforming canyon country. The Zephyr is one of the few outlets in my media diet that consistently does both of these things, and does so in an eclectic, engaging fashion.

That said, planning and zoning is an evergreen hot topic — besides what’s happening in Utah’s Dixie, see also the recent Moab and Spanish Valley moratoria — and it’s something about which I happen to know a little bit. So while I won’t remotely presume to speak for the publishers, I’m willing to engage in a more prescriptive way in the comment section with specific questions or observations, if you have them. Thanks for reading.

To comment, scroll to the bottom of the page.

Zephyr Policy: REAL NAMES ONLY on Comments!

Don’t forget about the Zephyr ads! All links are hot!

What do people do for work in St George? I’m curious what all the new migrants do to pay for those 400k+ homes.

And what is the water source for this clearly water-intensive form of development?

And at what point will “amenity migration” stop because the amenities are ruined?

Thanks for an informative, and depressing, article. I wonder when this ideal of the over-large home on the plot of irrigated grass will finally just die out…

I had plans to move to southern utah as I spent slot time there growing up enjoying the desert. After driving through there a couple of years ago and now reading this article I have no desire to move to that area. Sad to see how greed ruins a beautiful place. G

I share that sentiment. Such a marvelous area, such out-of-control growth.