This article first appeared in the Utah Historical Quarterly, and is reprinted with the permission of the author. Click Here to Read Part 1…

[Bates] Wilson had originally conceived a Canyonlands in which access would be substantially by jeep and hiking; however, his planning documents for Canyonlands throughout the 1960s dealt with construction of multiple sealed roads in the region, and throughout the 1960s he told [Senator Frank E.] Moss of such plans. (Note 17)

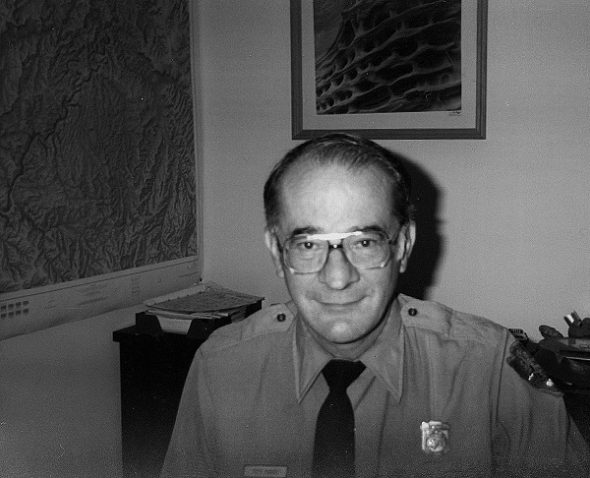

His first assistant superintendent, Roger J. Contor, also supported paved roads to Chesler Park. Contor had been brought to Canyonlands to handle the administrative side of the park by George B. Hartzog Jr., the autocratic director of the Park Service from 1964 to 1972. Hartzog saw himself “as seeking a balance between those who wanted parks to provide more roads . . . and those who wanted to protect the natural areas from being overrun by people.” (Note 18) Throughout his tenure he fought wilderness designation in national parks by maintaining that “natural environment lands” could have “minimum” facilities such as “one-way motor nature trails” and “informal picnic sites ‘for public enjoyment.’”(Note 19) He had instructed Contor to “keep the southeast Utahns happy” in terms of road development.

Contor, who later would be considered a strong environmentalist, had not yet developed his environmentalist ethic in the mid-1960s and would not have wanted to cross Hartzog at that stage of his career. (Note 20) As Contor later indicated, “Government employees basically avoid risk. . . . I wanted to be able to retire from the Civil Service.” (Note 21) In the 1960s, Contor, Chief Ranger James Randall, and Wilson were all enthusiastic about paving the White Rim road (now a unique and premier jeep and mountain biking route) in the Island in the Sky district in order to provide better access and visitation. This proposal was killed, however, by P. E. Smith of the Park Service’s Western Office of Design and Construction (WODC) who maintained that the primitive jeep road was for the few and “not the majority of visitors to the park.” (Note 22)

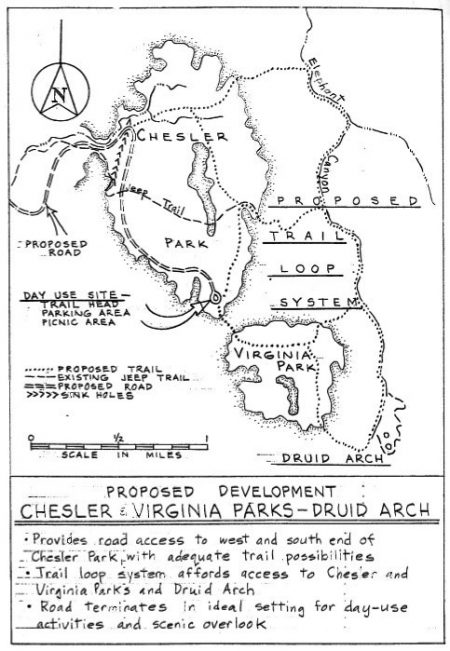

However, not all parts of the original Master Plan were favored. In September 1965, the acting chief of the Southwest Regional Office, which oversaw Canyonlands, commented about the nearly finalized Master Plan: “We agree that care should be taken in locating the loop road [within Chesler Park] to avoid intrusion,” to which Canyonlands administrative officer Kent Wintch noted, “Loop road cannot avoid intrusion” and Randall added laconically, “impossible.” (Note 23) Early in 1966 Wilson expressed his own doubts: “I awake during the night sometimes in a cold sweat, fearing that we will build a road into Chesler Park that would ruin it!” (Note 24) In September, Wilson indicated to his superiors that the interior paved loop road should be deleted and that the jeep road providing access into Chesler Park should be retained but not paved. (Note 25) Consequently, in his budgets after 1967, Wilson did not include funds for the loop road or paved access road. Yet, the change was not immediate, as even as late as March 1967 Wilson was allowing his landscape architect, Paul Fritz, to spend time surveying Chesler Park for possible road locations. (Note 26)

Wilson soon became concerned about allowing jeep access to Chesler Park at all. In the 1970s Wilson recalled the jeep road and its desecration of Chesler Park: “The jeeps were driving all over, not just on the original paths, killing the cryptogamic soil, creating ruts in all directions.” (Note 27)

In 1968 Edgar Kleiner and Kimball Harper of University of Utah completed a seminal study of the effects of limited cattle grazing from the 1890s to 1960s on plant type and growth, soil sustainability, and environmental degradation in Chesler Park, as compared to no domestic grazing in Virginia Park. Kleiner’s data, which Wilson saw, indicated clearly that limited winter cattle use in Chesler Park had caused irredeemable loss of habitat and soils by destroying the cryptobiotic cover, a degradation that might be irreversible. (Note 28) Irresponsible jeep driving off designated paths in Chesler Park had the potential to do more havoc in a shorter time period than had all the intermittent domestic grazing over the last century. While Wilson’s road plans in February 1968 still included paving the jeep road to the edge of Chesler Park (supported by his staff, including Contor), by the next month Wilson had requested from his superiors permission to actually close the jeep road to Chesler Park and begin instead construction of the spectacularly narrow Joint Trail that would provide hiking access into Chesler Park. (Note 29)

By early 1969, the decision had been made to close jeep travel into Chesler Park, although it still took two years for this to occur. When in October 1969 district ranger David Minor proposed blocking four-wheel-drive access into Chesler Park beginning in November, the then-assistant superintendent Joe Carithers responded that “it was [not] feasible to close the road to Chesler Park at the present time and it would be a question of timing when this would be feasible.” (Note 30) Carithers, who had been an aide to Udall and who would become instrumental in establishing preserved areas in Arizona, had been brought into Canyonlands to run “the nuts and bolts of the park,” as Bates Wilson “was doing mostly PR work” (Note 31) In April 1971, Wilson and the young ranger Jerry Banta (later to become superintendent of Canyonlands) finally closed the Chesler Park jeep access road.

Given these delays in closing even the rough road into Chesler Park, it is very likely that at least the road running to outside Chesler Park would have been paved had not the Vietnam War escalated just as Canyonlands was created. The siphoning of national monies for the Vietnam War impacted negatively the budgets for all domestic, discretionary funds. Hartzog remembered, “With the exploding growth of the National Park System from 1963–1972 (an average of nine new parks each year), and the escalating costs of the Vietnam War, our operating budget came under increasing pressure.” (Note 32) Hartzog’s comment is an understatement. The Park Service Capital Improvement Funds (from which road budgets derive) peaked from 1963 to 1965 ($72 million) and then fell precipitously because of the war to a low of $22 million in 1969. (Note 33) Moreover, between 1964 and 1972 the aggressive leadership of Hartzog led to the dramatic expansion of the Park system with the addition of seashores, urban areas, and a litany of historical sites. Given these additions, according to estimates of the Southwest Regional office in July 1965, “one half of our present tentative 1967 programs will have to be scrapped.” (Note 34)

One result of the budget crunch was that the entry road to Squaw Flat, which now brings visitors to the Needles Visitor Center, had been scoped out and graded by 1967 but not finished. In fact, in 1967 there was no road budget at all for Canyonlands. Only in 1968 was the $1.8 million finally budgeted to finish the Squaw Flat road; it was finally paved in 1971.

As for the other three proposed access roads, including the Kigalia Highway loop road, Wilson proposed for 1968 to 1970 that $5.3 million dollars be allocated for their construction. (Note 35) None of these monies were obtained in those years, however, because of the Vietnam War. In fact, by 1975, only the short road from Squaw Flat to Big Spring Canyon had been built. When in 1968 the San Juan County commissioners demanded an explanation of why even the road to Squaw Flat—let alone the road to Chesler Park—had yet to be finished, the National Park responded saying they were as keen as ever on finishing these roads. Even Utah Governor Calvin L. Rampton, upon his tour of Canyonlands in May 1969, commented that he sympathized with the Park Service for its lack of funds to construct roads. (Note 36)

Around this time, Wilson wrote his superior in the Regional Southwest Office, “the road to the Confluence Overlook holds higher priority than the road [from the south] to the junction west of Chesler Park. The Confluence is a logical destination, and one upon which various offices of the Service agree.” Wilson elaborated that engineering and management issues were unresolved concerning Chesler Park. Two weeks later, however, after being called down to the regional office, Wilson wrote to the office that “we enclose revised [roads] for construction towards Chesler Park rather than to the Confluence Overlook. We have embraced construction all the way to Chesler Junction in both cases. . . . In the event of fund shortages, it may be necessary to construct only portions of these [roads].” (Note 37) For budget planning it was summarized: “Assuming that the current freeze on contracting will be relaxed this winter, we hope to contract for another seven to ten miles of construction . . . this coming spring.” (Note 38) But the freeze did not end.

After another study team review, Wilson in March 1968 summarized the Canyonlands staff position on access roads: “No through road should be developed.” The Squaw Flat road “should end east of Elephant Hill.” (Note 39) Wilson indicated that he and the review team “didn’t want the country torn up.”(Note 40) Instead, the south road should come from “Dugout Ranch southwest and west to Beef Basin, then into the Park from the south, ending in Chesler Canyon south of Chesler Park. No roads should be built into Chesler Park.” (Note 41)

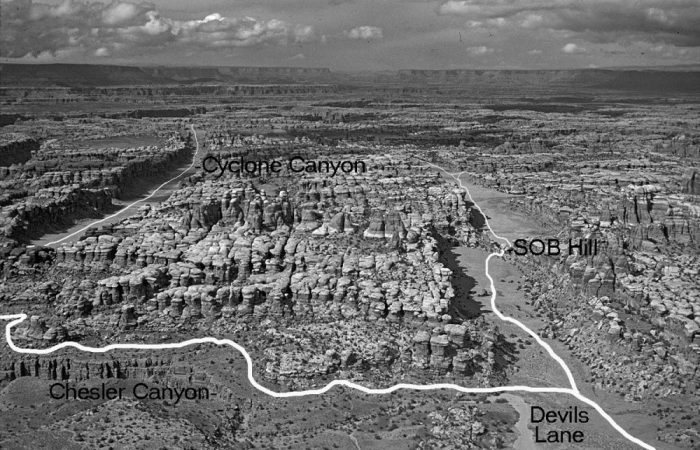

In May, Director Hartzog officially announced deferment of the proposed Squaw Flat to Chesler Park road on the basis that it “would violate the beauty and serenity of the Canyonlands’ country and would be a contradiction of national park purposes.” The plan instead was to build “a one-way loop road from the junction of Devils Lane and Chesler Canyon through Devils Lane to the confluence overlook and return[ing] via Cyclone Canyon.”(Note 42) This new plan, as Wilson indicated, would provide “for reasonable access” with “very little of the Needles . . . more than two hours’ hike from a hard surfaced road. What more can be asked?” (Note 43) Wilson’s staff again supported this plan. Contor believed the Cyclone Canyon/Devils Lane paved loop road, which would have destroyed the backcountry isolation of the Grabens region, to be “the best compromise between use and preservation of outstanding feature[s].” (Note 44)

These developments induced San Juan County officials to write to Senator Moss: “It now appears that the radical conservationists who would like to ‘lock up’ everything have achieved their goals through their lobby and planning in Washington by isolating Chesler and the Confluence from the main entrance and by requiring American people wishing to see Canyonlands to go to dead end roads.” (Note 45) Moss quickly responded that Wilson and the Park Service had assured him that the Squaw Flat road to the Confluence was not dead, just placed in second priority to the road from Dugout Ranch. But Moss immediately pushed Hartzog to commit to a new “special study team” to find access to the Needles District that would “not be destructive of the park resources.” (Note 46)

In July 1969 the report of that study team (members included Wilson and the assistant director of the Park Service, Gary Everhardt, who later as NPS director would be very supportive of the 1978 GMP) stated that the Squaw Flat to Confluence Overlook Road would be given first priority. The one-way road to outside Chesler Park would then be built from the Confluence. This ended the possibility of the “destructive” entry road from SR95 or Dugout Ranch. The new Republican-appointed assistant Secretary of the Interior Russell E. Train confirmed this to Moss in August 1969. (Note 47) The Confluence Road would be built, requiring a small bridge over Little Spring Canyon, a 700-foot bridge over Big Spring Canyon, and a 130-foot tunnel farther on.

Train’s 1969 decision ended questions as to which access roads were to be constructed. Vietnam funding restrictions delayed sealing of the Squaw Flat road until 1971, and fiscal years 1972 to 1974 were supposed to involve the construction of the road to the Confluence overlook. But the world of 1972 was no longer that of the 1960s

The road to the overlook now foundered on other fronts, even though more money would become available as the Vietnam War wound down. The 1969 National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) of 1969 required an Environmental Impact Statement (EIS) before any such project could begin. This EIS for the overlook road was not finished until October 1973. These delays exasperated Moss. In a speech to the Senate early in 1973, Moss lambasted the Park Service, saying that there was a “cabal in the Park Service—in the Department of the Interior itself—of staff people who for some reason or another [were] trying to prevent the completion” of roads. (Note 48) Even the early 1970s preservationist-minded Canyonlands superintendent Robert I. Kerr indicated, “I too was nostalgic for the good old days when if you wanted a road you just built it without having to prepare an Environmental Impact Statement.” (Note 49)

The draft EIS received many comments from the public and governmental agencies, with a surprising seventy percent saying “no” to the road, at least until a new master plan had been prepared. One environmentalist group suggested that the EIS was “incomplete, not supported by . . . basic engineering data, contradictory, and evidences major omissions of material required to be present in such documents.” (Note 50)

Other environmental groups went further and suggested, “Why then does the Park Service insist on building an unplanned road . . . with the full knowledge that at some date in the future it will probably conclude that to do so was a mistake?” (Note 51) In response to the EIS’s statement that it was critical to put in a paved road to allow summer tourists to see the Needles District, the Sierra Club replied, “True, travel in the hot summer months would be difficult, but so is travel in the high country of Sequoia and Kings Canyon National Parks during the winter. Yet no one advocates a network of roads and other facilities to change that situation.” (Note 52) The Department of the Interior under a Republican administration, however, was in control of the decision, and the final EIS concluded that the bridges, tunnel, and road would not adversely affect the environment. (Note 53)

By the time the Department of the Interior approved the EIS, Bates Wilson had retired (in 1972, apparently upon Hartzog’s insistence), and an environmentally responsive Canyonlands administration had taken control of the park. (Note 54) It was under the tenure of the two new superintendents, first Kerr and then Peter L. Parry (“an avid preservationist but not as much as Kerr”), that the new master plan, the 1978 GMP, was drafted, given community exposure and comment, and finally agreed upon by both the Park Service and the Department of Interior, then under a Democratic administration. (Note 55) This new document, prepared during the construction of the road to Big Spring Canyon from Squaw Flat, ensured that no bridge would be built over the canyon.

The GMP deemphasis on roads was the end result of a several-year process. In 1968 Wilson had prepared a statement of guiding principles for Canyonlands, saying that the original master plan, with its heavy emphasis on access, was flawed and that Canyonlands should be a park attuned to its fragile ecological community.

In December 1971 Wilson proposed a new master plan with new priorities: “[C]hanging attitudes and new values are constantly revealing past park planning efforts as having been born of naivety, lack of foresight and insufficient data,” leading to “one fortunate situation”—a “lack of development funds … a ‘problem’ that delayed realization of possible hasty decisions.” The document further emphasized “the simple feeling that the visitor need not (or even should not) be able to reach nearly every outstanding feature in a park, particularly at the expense of another individual’s experience.” (Note 56)

In compliance with then-current practice, outside consultants prepared a new master plan, completed in November 1973. In complete contrast to Wilson’s statements, the plan called for building roads to the Confluence overlook and to outside Chesler Park and paving most of the Kigalia Highway from SR95 to the south part of the Needles District. As a counterpoint, it proposed closing all jeep roads into the Chesler Park/Grabens region, as “jeep dust was killing plants adjacent to the road.” It criticized the alternative of no new roads as “a puristic approach . . . . not in the best interest . . . of the casual visitor who expects to see some portions of the park without undue effort.” Although the draft master plan admittedly would “damage [the park] by construction . . . and by large visitor impacts,” it dismissed the no-road alternative as creating a park “mostly as a large land reserve.” (Note 57) But as Parry later indicated, “thank goodness” the plan “was not acceptable to Bob Kerr.” (Note 58) J. Leonard Volz, Kerr’s supervisor at the Midwest Regional Office, agreed.

According to one of Kerr’s staff, the plan was too costly, and “closing all jeep roads was not politically possible . . . [as] Bates, among many other notables, was against that. It was a crazy idea. The enviro[nmentalist]s did NOT want to trade jeep road closure for a paved system in any way, shape, or form.” (Note 59) Moreover, the argument that jeep roads needed to be eliminated because of lethal “jeep dust” appears to have had no validity in the real world. (Note 60) Under Kerr, this draft plan consequently disappeared, as it never was officially sent upstream within the Park Service, leaving Canyonlands without a current master plan. (Note 61)

Meanwhile in 1974 Kerr indicated that “I shudder at the connotation of the ‘loop road,’” going “on record as opposing a paved road—or an improved dirt road.” (Note 62) He also decided that the road over Big Spring Canyon to the Confluence would fail on its own and that he would not fight to keep the road to Big Spring Canyon from being built. “The bridge would be too expensive to ever be built,” he later said. “So, it would be better to not contest the road to Big Spring Canyon. Why bring in the big guns, like the Sierra Club, to fight San Juan County over this dead end road and create so much ill feeling and animosity. At least the road would take people to a nice overlook of the canyon and satisfy southeast Utah residents. Someone else could deal with not building the bridge.” (Note 63) This someone else became the new superintendent, Pete Parry. Parry, who never shied from controversy, actively sought the Canyonlands superintendency, indicating he “got dust in my blood and my liking for the desert” when he was superintendent of Joshua Tree National Monument. (Note 64)

In his draft GMP in 1976, Parry called for a road to the Confluence that did not leap Big Spring Canyon. His final GMP did not change this view. He stated this decision was consonant with community views: of the 995 letters they received on the subject, 980 were against the bridge. Again, Parry’s supervisors fully supported this GMP. (Note 65)

Three critical factors led to the approval of the 1978 GMP. First, in the early 1960s, planners had not comprehended how much money it would take to build the proposed roads. By 1978, much of the sentiment against the road to the Confluence and all subsequent road extensions was due to cost. The 700-foot bridge across Big Spring Canyon alone required $11 million in 1977 ($44 million in today’s dollars) with another four to seven million dollars just to get to the Confluence, dwarfing the entire annual Canyonlands budget. (Note 66)

The oil difficulties and high gasoline prices of the 1970s had reduced tourist visitation to southeast Utah and “millions, each year” were not clamoring over the area as originally forecasted. Even the accessible Island in the Sky unit of Canyonlands, immediate adjacent to Moab, only had some 40,000 visitors annually throughout the 1970s. Therefore, it was difficult for the Park Service to justify spending enormous money for a dead-end road to the Confluence. As indicated by one of Parry’s staff, neither Udall nor San Juan County had understood “that drawing lines for roads on paper had no correspondence with reality on the ground. It would cost billions to put that road in, with all of the wash crossings and terrain to navigate.” “There never was going to be enough money to build that road [Kigalia Highway and road to the Confluence].” (Note 67)

Second, a different group of individuals controlled the creation of the 1978 GMP as compared to that of the 1965 Master Plan. Originally, satisfying the locals was a primary goal, for the park could not have been created without local support. Hartzog, Udall, and Wilson apparently felt compelled to favor local desires in the 1965 Master Plan. Parry had no such compulsions. He differentiated “protection of the resource,” in this case, allowing road development in the Needles District, from that of “preserving an experience that people . . . love . . . [and] they’ll never forget.” To Parry, “Canyonlands wasn’t a traditional park, and it was a kind of wild park,” unlike Arches, with its “paved access roads, drive-through” experience. (Note 68) And now that Canyonlands was an established national park, the whole country’s citizenry, not just southeastern Utahns, were to be listened to.

Parry consequently held a number of meetings to obtain input on his plan. The meetings, as was the norm, were held at localities adjacent to the park within the state and other places in adjacent states. After the NPS announced it would accept letters on this issue, environmental groups instigated a letter-writing campaign. When it turned out that San Juan County commissioner Calvin Black (known locally as the “Governor of San Juan County”) did not similarly persuade a horde of locals to write their views, Parry responded, “Well if they don’t care enough to get their supporters to write letters, it just indicates that they really don’t care enough about this issue at hand and they will have to endure the consequences.” (Note 69)

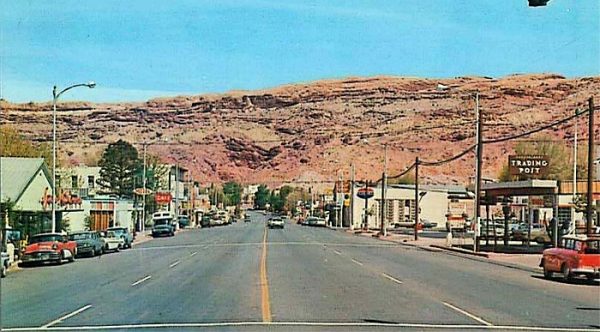

The local meetings, held in September 1976, went generally as expected. At the Monticello meeting (seventeen attended) the consensus was for more access roads everywhere. Discussions at the two Moab meetings (fifty-five attendees) were split, with no consensus being reached on road development. At Green River (unaffected economically by the issue) all five attendees opposed building the road to the Confluence. One local rancher summarized their views: the roads should remain “at least as bad as they are now.” (Note 70)

Farther away, in Salt Lake City, Denver, Grand Junction, and Phoenix, the sentiment was against the road to the Confluence; for instance, 95 percent of the hundred attendees in Denver were against constructing the bridge over Big Spring Canyon. (Note 71) Therefore, Parry was not lying when he said people opposed the bridge. It just depended on whom he asked, and he mainly asked urban, non-southeast Utah individuals. Moreover, the attendees at these non-local meetings were largely former park rangers, jeepers, college students, and environmental group members. Once Parry and his staff came up with the GMP, it would be a foregone conclusion that it would be accepted; as one staff member concluded, “of course, we knew this was how it would turn out.” (Note 72)

Third, the GMP in 1978 came after a renaissance in ecological and environmental awareness that was not nationally prevalent in 1962, when the blueprint for road access to the Needles District was created. These intervening years saw the profound influence of Rachel Carson’s seminal Silent Spring and Edward Abbey’s rousing Desert Solitaire. Major environmental battles and accomplishments took place in the 1960s: the Wilderness Protection Act of 1964; the 1969 Environmental Protection Act; the Leopold Report and the National Academy of Sciences Report strongly condemning the Park Service for not using a scientific and ecological basis to prevent impairment of its vast national parks; and the fight over a dam that would flood parts of the Grand Canyon. (Note 73)

Next Time, A National Debate on Environmentalism Becomes Local Debate on Access…

Clyde L. Denis is Professor of Biochemistry at the University of New Hampshire.

My thanks to Vicki Webster of Canyonlands National Park who facilitated my easy access to many of the documents cited in this article…

Footnotes:

17 Lloyd M. Pierson, “Looking Back on Canyonlands author; Bates Wilson to Frank E. Moss, January 12, 1971, fd. 673, Canyonlands Collection. National Park Formation,” typescript in possession of

18 Frank P. Sherwood, “George B. Hartzog, Jr.: Protector of the Parks,” in Exemplary Public Administrators: Character and Leadership in Government, eds. Terry Cooper and Dale Wright (San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, 1992), 147.

19 Craig W. Allin, The Politics of Wilderness Preservation (Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 1982), 146–47, 150–51; Michael Frome, Regreening the National Parks (Tucson: University of Arizona Press, 1992), 72.

20 Alexander interviews.

21 Michael E. Fraidenburg, Intelligent Courage: Natural Resource Careers That Make a Difference (Malbar, FL: Krieger, 2007), 12.

22 P. E. Smith, Acting Chief, WODC, to Regional Director, South West Region, September 9, 1965, fd. 180, Canyonlands Collection; Superintendent Bates Wilson to Regional Director, Southwest region, September 27, 1965, fd. 180, Canyonlands Collection; Master Plan Brief for Canyonlands National Park, August 4, 1965, fd. 181, Canyonlands Collection; Roger J. Contor to Owen W. Burnham, October 10, 1967, fd. 181, Canyonlands Collection.

23 Acting Chief, WODC, to Regional Director, Southwest Region, September 9, 1965, comments made September 13, 1965, fd. 180, Canyonlands Collection.

24 C. Sharp, “Differences of Opinion on Routes Develop on Interagency Tour,” Times-Independent, April 28, 1966. 1.

25 Bates Wilson to Chief, Office of Resource Planning, SCC, September 22, 1966, fd. 180, Canyonlands Collection.

26 Canyonlands Complex Staff Meeting Minutes (CCSMM), March 29, 1967, Folder 42, Canyonlands Collection.

27 Alexander interviews.

28 Edgar F. Kleiner to Bates Wilson, May 16, 1968, and Kimball T. Harper to James W. Larson, Acting Deputy Chief Scientist, September 16, 1968, fd. 753, Canyonlands Collection.

29 CCSMM, March 20, April 3, and April 17, 1968, fd. 43, Canyonlands Collection; Bates E. Wilson to the Regional Director, Southwest Region, March 11–26, 1968, fd. 181, Canyonlands Collection.

30 CCSMM, January 20, 1971, fd. 46, Canyonlands Collection; CCSMM, October 1, 1969, fd. 44, Canyonlands Collection.

31 Joseph Carithers, interview by John R. Moore, 1994, Big Bend Oral History Project, University of Texas at El Paso Oral History Institute; Paul L. Allen, “Obituary of Joseph F. Carithers,” Tucson Citizen, July 4, 2001.

32 George B. Hartzog, Jr., Battling for the National Parks (Mt. Kisco, NY: Moyer Bell Limited, 1988), 152.

33 Wirth, Parks, 237.

34 George W. Miller to Bates Wilson, July 23, 1965, fd. 243, Canyonlands Collection.

35 Bates Wilson to Regional Director, Southwest Region, January 4, 1967, fd. 243, Canyonlands Collection.

36 Canyonlands National Park (Existing) Program Summary, March 1967, fd. 176, Canyonlands Collection; Bates Wilson to Regional Director, Southwest, May 21, 1969, fd. 181, Canyonlands Collection.

37 Bates Wilson to Regional Director, Southwest Region, January 31, 1967, fd. 243, Canyonlands Collection.

38 Roger J. Contor to Owen W. Burnham, October 23, 1967, fd. 181, Canyonlands Collection.

39 Document on Recommended Changes to Roads and Development in Master Plan, March 11, 1968, fd. 181, Canyonlands Collection.

40 “Canyonlands Park Officials Outline Details of Proposed Master Road Plan Alternatives,” Times Independent, October 24, 1968, 2

41 CCSMM, April 12, 1967, fd. 42, Canyonlands Collection.

42 News Release, Department of the Interior, May 8, 1968, fd. 176, Canyonlands Collection.

43 “Canyonlands Park Officials Outline Details of Proposed Master Road Plan Alternatives,” 2.

44 CCSMM, April 12, 1967, fd. 42, Canyonlands Collection.

45 San Juan County Commission to Frank E. Moss, October 16, 1968, fd. 673, Canyonlands Collection.

46 Frank E. Marion to W. Hazleton, Chairman, San Juan County October 28, 1968, fd. 673, Canyonlands Collection.

47 Russell E. Train to Frank E. Moss, August 28, 1969, fd. 286, Canyonlands Collection.

48 Frank E. Moss to Interior and Related Agencies Subcommittee, Senate Appropriations Committee, May 9, 1973, fd. 286, Canyonlands Collection.

49 Robert I. Kerr, phone interviews by author, May 2013 to August 2014

50 U.S. Department of the Interior, Final Environmental Statement: Proposed Squaw Flat-Confluence Overlook Road, 1973; Moab Chapter of the “Interested in Saving Southern Utah’s Environment” to Robert I. Kerr, Superintendent, Canyonlands National Park, September 18, 1972, fd. 692, Canyonlands Collection.

51 Sierra Club to Nathaniel P. Reed, Assistant Secretary for Fish, November 15, 1972, fd. 286, Canyonlands Collection.

52 DOI, Final Environmental Statement; Sierra Club to Superintendent Robert I Kerr, September 19, 1972.

53 DOI, Final Environmental Statement, 5.

54 Hartzog apparently harbored a deep-seated resentment for Wilson’s independence in establishing National Parks (an area that was supposed to be Hartzog’s unique legacy), Wilson’s ability to get things done in Washington, D.C. without Hartzog’s help, and Wilson’s deep friendship with Udall, whom Hartzog did not like. Hartzog’s actions against Wilson are consonant with other comments on Hartzog. See Sherwood, “George B. Hartzog, Jr.: Protector of the Parks,” 174; Frome, Regreening, 73–74.

55 Alexander interviews.

56 Office of Environmental Planning and Design, WSC, “Master Plan Study, Canyonlands National Park,” December 1971, fd. 181, Canyonlands Collection.

57 The Environmental Associates: Architect Planners, Landscape Architects, “Canyonlands National Park Master Plan,” November 1973, fd. 184, Canyonlands Collection; National Park Service, “Environmental Statement: Master Plan of Canyonlands National Park,” November 1973.

58 Peter Parry, interview by Samuel Schmieding, Moab, Utah, June 2, 2003, Schmieding Oral Histories, CANY 45551, Canyonlands Administrative History Project Oral History Component, Canyonlands Collection.

59 Alexander interviews.

60 Edgar Kleiner and Jayne Belknap, email interviews by author, February 2016.

61 Alexander interviews.

62 Robert Kerr to State Director, Utah, February 13, 1974, fd. 319, Canyonlands Collection

63 Kerr interviews.

64 Parry interview.

65 Alexander interviews; George Raine, “Conflicts Rise over Use of Utah Park,” New York Times, August 2, 1981.

66 National Park Service, An Economic Study of the Proposed Canyonlands National Park and Related Recreation Resources, by Robert R. Edminster and Osmond L. Hartline, 176; Frank E. Moss, 87th Cong., 2d sess., Congressional Record (March 28, 1962).

67 Alexander interviews. In today’s dollars to put a road to the Confluence overlook would have be at least about seventy million, to pave the roads to outside Chesler Park about 120 million, and to reach State Road 95 another 1.5 billion

68 Parry interview.

69 Alexander interviews.

70 U.S. Department of the Interior, National Park Service, Assessment of Alternatives, National Park Service, General Management Plan, Canyonlands National Park, Utah (Denver, August 1977), 96.

71 Ibid.

72 Alexander interviews.

73 Dilsaver, ed., America’s National Park System, 278; Alfred Runte, National Parks: The American Experience, 2d ed. (Lincoln: University of Nebraska, 1987), 191.

To comment, scroll to the bottom of the page.

Zephyr Policy: REAL NAMES ONLY on Comments!

Don’t forget the Zephyr ads! All links are hot!