This article first appeared in the Utah Historical Quarterly, and is reprinted with the permission of the author. Click Here to Read Parts 1 and 2…

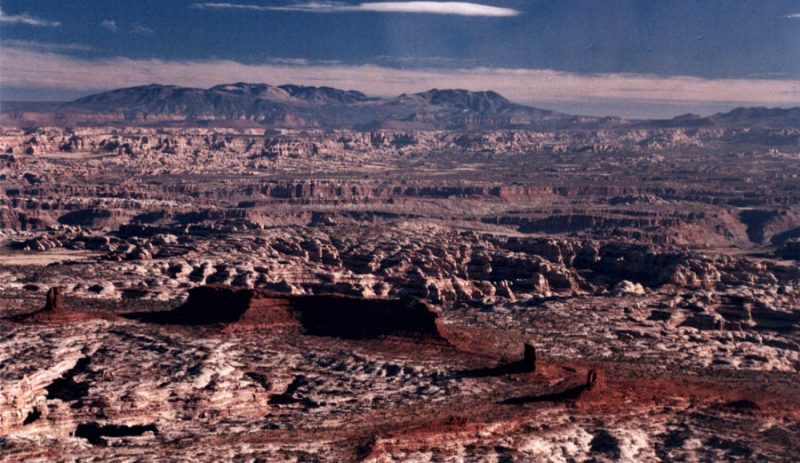

To assess the effect of national environmental discussions on road access in the Needles District, it is illustrative to compare the 1962 community comments during the congressional hearings on establishing Canyonlands with comments on the draft General Management Plan (GMP) of 1976. In 1962, about 60 percent of the comments by San Juan County residents opposed establishing a large Canyonlands park. The majority favored three much smaller units with all of the intervening lands open to resource development and extensive road development within all three units. In 1976, the consensus of Monticello was for complete road building throughout the Chesler Park/Grabens region to attract maximum tourist visitation and boost San Juan County business. In 1962, Moab was equally split between those favoring a large park and those favoring the Monticello model of smaller parks. In 1976, Moab similarly could not reach consensus about the road access question. Therefore, in southeast Utah there was no change in attitudes between 1962 and 1976, and economic development remained the paramount concern.

The rest of the country was unaffected by economics in regards to Canyonlands. In 1962, the vast majority of people who commented at the Salt Lake City and Washington, D.C. hearings favored the largest Canyonlands possible, but it is clear they generally also favored road access (three to one among those who commented about roads), consistent with national attitudes at the time. But by 1976, all groups at meetings outside of southeast Utah reached the consensus that no more roads in the Chesler Park/ Grabens region should be built. This change in attitude appears to be the result of the national change in attitudes concerning the preservation of wilderness-like areas that Canyonlands embodied.

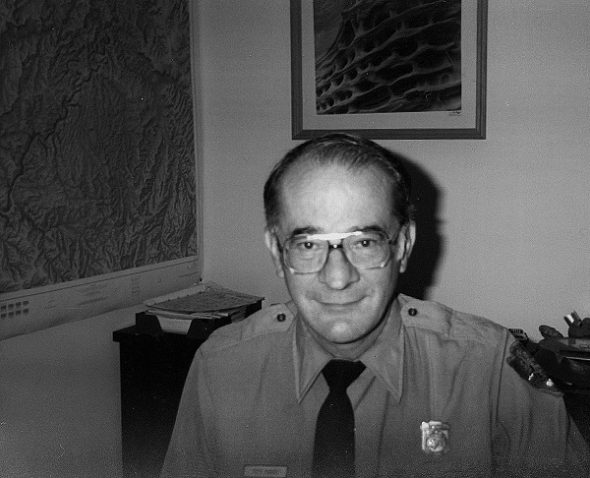

From 1962 to 1976, San Juan County essentially lost control of Canyonlands National Park. The people immediately in charge of making decisions about roads through the Chesler Park/ Grabens region after 1972 were superintendents Kerr and Parry, unencumbered by connections to Moss, and his replacement in 1976, Republican Senator Orrin Hatch (a good friend of Calvin Black). While Kerr indicated that going against San Juan County’s wishes meant that ill feelings and conflicted Park Service interactions with the local constituents would become the norm, it was ultimately Parry and his successors that paid this price. San Juan County in 1978 “severed . . . diplomatic relations” with the Park Service and “terminated deputy sheriff commissions and bail bondsmen’s authority . . . accorded Park Service personnel.” (Note 74) It also persuaded Utah’s congressional representatives to not support President Jimmy Carter’s proposal for 287,985 acres of wilderness in Canyonlands in 1978, ending the opportunity for most of Canyonlands to be officially designated as wilderness. In the following years, motions and statements by the San Juan County commissioners were routinely presented stating that “the sooner Mr. Parry is replaced, the better off San Juan County will be,” and that “Pete Parry is an enemy . . . to San Juan County.” (Note 75) San Juan County animosity toward Canyonlands, unfortunately, remains present today, with traditionalist locals avoiding hiking in the Needles District and viewing it as “the black hole of San Juan County.” (Note 76)

Ironically, all of the roads conceived in the original 1965 Canyonlands Master Plan would probably have been constructed in the 1950s had a proposal for the Escalante National Monument been approved in the late 1930s. This monument would have placed all of the Canyonlands area under Park Service control around the time Arches National Monument was created. Arches did not have hard-surfaced roads until the late 1950s, when “access” was dominant in the Park Service and Mission 66 funds became available. It can be reasonably assumed that had an Escalante National Monument been created, a road to and within Chesler Park would also have been paved, and there would have been no backcountry to Canyonlands.

The Needles District road access debates of the 1960s and 1970s illustrate continuing decisions about national land use and availability. Often, local economic benefits, as those for southeast Utah and particularly San Juan County, have to be weighed against broader interests—in this case, preservation of a little-known area. But such discussions have to be grounded in a clear understanding of whether local economic benefits will occur from development, and whether sacrificing preservation is warranted. For Canyonlands, it is not certain that construction of all the roads in the Needles District would have propelled Monticello and Blanding to the economic development they desired. For one thing, as remarked on by Parry, “I could never understand why Cal [Black of San Juan County] wanted that road so badly. Just look at the map. If tourists left the Needles by way of his Kigalia Highway, they would have bypassed both Monticello and Blanding and all the businesses that would have benefitted from the tourist traffic. It made no sense.” (Note 77)

Critically, although Monticello was twenty-four miles closer to the Needles District than Moab, it was from Moab that tourists launched their visits. Monticello lacked the immediate red rock ambience that Moab had in abundance, with its adjacency to Arches National Monument. Moreover, Moab, not Monticello, was geographically situated to benefit from the tourism industry, being the first entry to the Canyonlands region for visitors from the north and east and from California traveling to Bryce and Zion. (Note 78) Importantly, in 1962 the economically depressed community of Moab offered more community services and amenities for the traveler than did Monticello: thirteen motels in Moab compared to five motels in Monticello, seven overnight trailer courts compared to none, and thirteen restaurants compared to eight. Grand County had three times as many tourist-related jobs, mainly located in Moab, than did San Juan County. (Note 79) All these factors were known at the time and were the reasons why the Canyonlands headquarters became located in Moab rather than Monticello.

Central to these discussions are the philosophical views of the individuals who wield the power to either promote or limit access to remote and undeveloped natural areas. Wilson and his staff, including Contor and Carithers, and Wilson’s superiors, Hartzog and Udall, initially all favored automobile access by the casual visitor. There is no evidence that contacts with Senator Moss or with San Juan County were forcing their hands on this issue. But times changed. Key to this shift in attitudes is the difference between protection and preservation inherent in the Organic Act’s use of the word “conserve.” Bates Wilson helped protect and thereby conserve the Canyonlands area when he promulgated the need for a national park, but that did not mean philosophically he had arrived at the position of preserving it. Protection implies restricting outside incursions while preservation implies limiting internal development. This difference is grounded in the intersection of ecological and emotional concerns. While Wilson eventually transitioned into favoring preservation of the Needles District, it was Kerr and Parry, upon their respective arrivals, who were philosophically attuned to these differences, and it was ultimately Parry who scotched the road projects. While it can also be argued that Parry was not unique and that any other superintendent of 1976 Canyonlands would have done the same, individuals do matter. Harvey Wickware, the 1990s Canyonlands superintendent who eventually paved the access roads in Island of the Sky (favored by Parry in 1978 as a sop to not paving the Needles District), indicated that had he been superintendent in 1976, “I would have paved the road to outside Chesler Park and the road to SR95 and probably the road into Chesler Park.” (Note 80)

Although many in southeast Utah might still feel that “locals were sort of duped into a plan that Washington never intended to follow” and “the Park Service [ordained] from the outset . . . that Canyonlands would be designed to exclude people,” it is clear that the federal government throughout the 1960s had no intention of misleading rural Utahns. (Note 81) Initially, local support evinced by southeastern Utahns and Senator Moss was aligned with national concerns about protection of scenic, archaeological, and natural areas in Canyonlands. Wilson in the early 1970s indicated that in these situations one has to take the very long-term view and not worry about the immediate battles lost or won. The long-term goal was to establish the park and protect its great scenery. The future would take care of the rest. People’s attitudes would change, but no matter what happened, the area would be protected with some access roads or none. (Note 82) Udall, in contrast to Wilson, indicated in 1977 that he had no “memory of [any such] . . . commitment [as to road access] . . . [although] compromises were reached with then Senator Frank Moss,” adding in 1981, “I think there may have been some misunderstanding about development.” (Note 83) But there had been no misunderstanding. Udall’s Interior Department published in 1962 a proposal with roads to the Confluence overlook and to and around Chesler Park. (Note 84) The early 1960s congressional hearings and later letters clearly indicate that Moss, Udall, Wilson, and the Park Service were in agreement on road access, at least to outside Chesler Park.

Instead, what happened, as indicated in Wilson’s 1972 proposal for a new Canyonlands Master Plan, the delay in road construction caused by the financial restrictions imposed by the Vietnam War had created an opportunity to rethink road development for the Park. Individuals, such as Wilson, who were connected to the Park on the ground and intimately engaged in learning about its ecosystem interactions and fragility, moved away from their initial thoughts and became more receptive to new viewpoints. Wilson’s changed views were summed up in his quip, “I don’t think . . . that every point of interest should be open to a pink Cadillac.” (Note 85)

In contrast to Wilson’s evolution in thinking, local individuals not daily involved in the Park (e.g., southeast Utahns and Moss) still had to contend in the 1970s with the same lack of local economic development issues as they did in the early 1960s. For Moss, preservation issues had never been high on his list. Moss’s congressional specialties were primarily in consumer affairs and restricting tobacco advertising. Even though he was eventually responsible for several national parks in southern Utah, in terms of environmental issues, he was ranked fairly low by the League of Conservation Voters. (Note 86) He believed in allowing all people access to national parks rather than preservation, where visitation was limited to “just a few who can afford horseback riding or hiring of jeeps, or otherwise have a lot of time to get into the wild parts of our area.” (Note 87)

But by the mid-1970s the decisions for road access had switched from local control to national interests receptive to preservation and environmental issues. Superintendent Parry, who from the onset was not dead set against paved road development in Canyonlands, became sympathetic to these national concerns and felt, according to one staff member, that “people driving through Canyonlands desire dust in their trunks.” (Note 88) Therefore, his 1978 GMP derived its philosophy from the original language in the act for the founding of Canyonlands in 1964: “The purpose of the park . . . is to preserve an area.” (Note 89)

—

Clyde L. Denis is Professor of Biochemistry at the University of New Hampshire.

My thanks to Vicki Webster of Canyonlands National Park who facilitated my easy access to many of the documents cited in this article…

Footnotes:

74 Raine, “Conflicts Rise Over Use of Utah Park.”

75 San Juan County Meeting Minutes, June 27, 1983, January 14, 1985.

76 Bill Boyle, “How San Juan County’s crown jewel became San Juan County’s black hole,” San Juan Record, March 13, 2013, 5.

77 Jim Stiles, “Unsung heroes of the canyon country #1: Pete Parry,” Canyon Country Zephyr (August/September 2012).

78 Robert L. Barry, “The Local Interest as a Consideration in the Planning of Highway Construction in the Canyonlands Region of Southeastern Utah” (M.S. thesis, Utah State University, 1973), 1–147; Michele L. Archie, Howard D. Terry, and Ray Rasker, Landscapes of Opportunity: The Economic Influence of National Parks in Southeast Utah (Salt Lake City: National Parks Conservation Association, 2009), 4.

79 Environmental Associates, Inc., Transportation Study: Arches, Canyonlands, Capitol Reef National Parks, Utah (Washington, D.C.: National Park Service, 1973), 24–25; Edminster and Harline, An Economic Study, 85.

80 Harvey Wickware, interviewed by author, Moab, UT, September 2014; Parry interview.

81 For local reactions to the park, see Sena Taylor Hauer, Times Independent, February 21, 2013; Raine, “Conflicts Rise over Use of Utah Park.”

82 Alexander interviews.

83 Briefing Statement, Confluence Overlook Road, from National Park Service, November 21, 1977, fd. 286, Canyonlands Collection; Raine, “Conflicts Rise over Use of Utah Park.”

84 U.S. Congress, Senate, Subcommittee on Public Lands, Proposed Canyonlands National Park in Utah: Hearing before the Subcommittee on Public Lands of the Committee on Interior and Insular Affairs, 52–58; Edwards testimony in U.S. Congress, Senate, Subcommittee on Public Lands, Proposed Canyonlands National Park in Utah: Hearing before the Subcommittee on Public Lands, 38.

85 George Raine, “Conflicts Rise of Use of Utah Park,” New York Times, August 2, 1981.

86 Cornfield and Zill, “Frank E. Moss, Democratic Senator of Utah.”

87 Moss to Interior and Related Agencies Subcommittee, Senate Appropriations Committee, May 9, 1973.

88 Alexander interviews; Thomas C. Wylie, phone interview by author, February 2016.

89 Assessment of Alternatives, 5.

To comment, scroll to the bottom of the page.

Zephyr Policy: REAL NAMES ONLY on Comments!

Don’t forget the Zephyr ads! All links are hot!