“I am not a naturalist. I never was and never will be a naturalist. I’m not even sure what a naturalist is except that I am not one…The only birds I can recognize without hesitation are the turkey vulture, the fried chicken, and the rosy-bottomed skinny dipper. My favorite animal is the crocodile.”

–Edward Abbey, Desert Solitaire

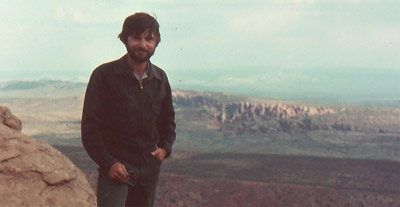

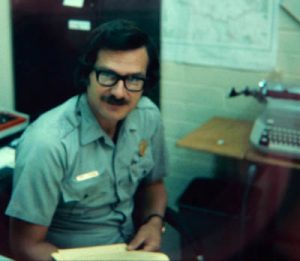

If there was ever an Arches ranger who was hired with even fewer qualifications than Cactus Ed, it might have been me. I had no educational background in the natural sciences. My degree was in a totally unrelated field, and I had lived most of my life in a very different environment, 1500 miles east in the humid green hills of Kentucky.

In my favor, I had been a Boy Scout and I had good intentions. I’d read “Desert Solitaire” four times and I was wildly, passionately, head-over-heels in love with the canyon country. I was an Ed Abbey Groupie. Ultimately, I was hired because my boss, Jerry Epperson, thought I “showed potential,” and also because I was the only person who applied for the job.

Despite my shortcomings, I was determined to live up to that “potential” and self-educate myself to the natural wonders around me. I devoured all the relevant books in the park library and read the reams of old Arches monthly reports. And I sought the good company and knowledge of my fellow, more experienced rangers, who were willing to be mentors of a sort. I was an eager student and was able to learn enough—like cramming for finals—to at least provide rudimentary answers to most of the visitors’ questions. As time passed, my understanding of the park’s resources grew. My proudest moment came years later, when I was able to differentiate between a long-billed curlew and a marbled godwit!

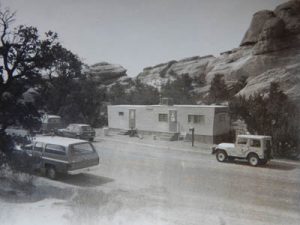

Arches was teeming with wildlife and because the road traffic and visitation back then was only a fraction of what it is now, they were more likely to be spotted in the front country. I was also the only ranger living inside the park–right smack in the middle, in fact, at the Devils Garden— and consequently, my opportunities to commune with the critters became a 24/7 experience.

Over the next decade I developed almost an intimacy with the wildlife. By sunset, most of the tourists had “headed down the hill,” as we used to describe the nightly exodus, and the nocturnal critters crept out of the shadows and into the cooling dusk of an evening.

First came the Mule Deer, who stepped tentatively from the tall Entrada sandstone fins and into the center of the Devils Garden “trailhead meadow” that in 1966 had been encircled by a paved road. But the deer didn’t mind the pavement, and as you’ll see, some of the wildlife preferred it. It was the threat of the mechanical monsters at high-speed that posed the greatest threat of all in our otherwise “protected” parkscape.

I learned to recognize many of the deer on sight; one particular buck displayed an unusual twist of one tine on his right antler. He was magnificent. Years later, I found his skeletal remains near the Upper Fiery Furnace. It was like finding the grave of an old pal. We later named an arch for him, in his honor and memory—Big Buck Arch.

Even within a stone’s throw of our dilapidated government tin trailer, or closer, the animals kept me company. Inside, of course, the deer mice were my closest companions. They even built nests in my underwear drawer. Imagine my surprise, reaching for a pair of shorts and hearing them squeak. Years later, when the NPS condemned the old tin beast and pulled off the interior walls, they found deer mouse droppings had accumulated to a depth of about 18 inches. It’s why I’m convinced I have a built in immunity to the Hantivirus. If only it applied to COVID-19 as well.

Outside, in my “back yard,” I was always careful to carry a flashlight after dark. Porcupines often hung out near the septic tank leach field and I once almost stumbled into one of the prickly fellows.

Five miles below us on the park road, there was an incredibly stupid or unbalanced jack rabbit that regularly hung out near Panorama Point. We became a part of each other’s nightly experience during my evening patrols. On most nights he liked to jump out on the roadway in front of me, and run just ahead of the park truck, weaving from side to side like the drunken hare he must have been. But occasionally, when he was really feeling out of sorts, Jack preferred to aim straight at me, like a crazed kamikaze rabbit. It was me and a hare playing chicken. When head-on collisions seemed inevitable, I’d finally accept defeat and swing to the shoulder, as the long-eared lunatic shot by me like a Saturn rocket…a low-slung blur, hugging the yellow center line.

A kit fox family resided near the Fiery Furnace; I’d often see them illuminated in my headlights as the road bent to the north. They lined up side-by-side, as if to pose. I still remember the coyote that liked to watch the sunrise near the old pipe line.

Just up the road, near the Upper Fiery Furnace, a pair of Redtail Hawks renewed their familial ties to the park each spring when they resurrected their nest along a ledge of Dewey Bridge sandstone, less than 100 yards from the park road. Year after year, they’d return to their nest, make the necessary modifications and start another family. I could easily observe their progress as I made my daily patrols.

Go another mile to Doc Williams Point. On many nights during the summer, I encountered a rather ill-tempered rattlesnake, the midget faded as they were identified. I’m sure it was the same fellow because there couldn’t be that many stubborn rattlers residing so frequently on the same patch of asphalt. In the desert, the temperatures can reach 100 by day, but because the air is so dry, the thermometer can plummet once the sun sets–there’s no moisture in the air to retain that warmth. The snakes, cold-blooded little creatures that they are, seek external warmth at such times, and nothing holds the heat better than miles of black asphalt and tar.

And so, night after night, I’d encounter the snake. Same time. Same place. But unlike most other snakes I’ve met, who will avoid a confrontation if possible, this ill-tempered reptile made it his habit to stand tough and refuse to yield the ground. Prodding him with a rake didn’t help; he’d strike the tines with his fangs although he was careful not to release his venom. He was saving that for me.

Finally, ol’ Evil Eye would slither off the pavement, albeit reluctantly, but I always assumed he came back as soon as I left. The libertarian in me concluded that ultimately, it was his choice and if winding up squashed by a 32 foot Winnebago was the destiny he wanted for himself, then so be it.

And then there were the cats. You rarely saw the cats. Only two types of felines reside in this country, and when any of the rangers actually saw a bobcat or, even rarer, a mountain lion, they were the envy of the staff. Even finding their sign or a track was an event to be relished. But sometimes we got lucky.

One perfect morning in June, I set out to find a petroglyph I had heard about from fellow ranger Kay Forsythe. Kay was the seasoned veteran (the seasoned seasonal) when I was the rookie ranger. It was Kay who taught me to be reticent about revealing secret places and hidden treasures. I am proud to say that I have grown up to emulate Kay and be pretty damn reticent myself. But Kay would occasionally take pity on me. In this instance, she tossed me the vaguest of hints…a general direction. One of those, “Oh you know…sort of over there” kinds of clues.

Armed with this fragment of information, I stepped into the morning sunlight, in search of my petroglyph, but I never got that far. Side canyons have a way of distracting me, and as usual, I could not resist the temptation to see what surprises this one might hold.

It turned out to be a short trip. The canyon boxed out in a jumble of boulders, none of which were big enough to allow access to the rim. Still, I thought a scramble up the rocks might give me a nice view back to the canyon’s mouth, so I started to pick my way to the top.

I had not climbed more than ten feet, when I heard an odd sound.

Rrrrrmmmmmmm.

Amazing, I thought. It sounded like a car revving its motor, somewhere down below on the park road. Sounds travel in the dry desert air. You can never get away from the noise of those damn machines, I groused. I took another step.

Rrrrrrrrrrmmmmmmmmmmm.

I paused. Bewildered. What kind of a car is that, anyway? Onward and upward.

RRRRRRRRRRRRMMMMMMMMMMMMM!!!

I looked up and there, practically in my face, was a bobcat. She was peering around the corner of a boulder staring at me through the most intense amber eyes I have ever seen. Utterly motionless, she continued to…well, sort of hum at me. I stumbled backwards down the pile of rocks and regrouped in the sandy wash below. There, I noticed the remains of a recently eaten cottontail–all that was left were the little guy’s feet. So much for bringing good luck. I glanced back at the top of the boulder pile and was surprised to see that the bobcat was still there. In fact, she had positioned herself, sphinx-like, on top of the highest rock, and continued to stare at me.

I would bet that neither of us blinked for five minutes. While we tried to stare each other down, I wondered why she found me so interesting. I remembered that most bobcats breed in late winter and that their young are born in the spring, after a gestation period of around 70 days. And since they make their den in a rock pile or crevice, it was safe to assume that somewhere up there in the rocks, three or four kittens were waiting for Ma to return.

But I wasn’t quite ready to leave. I knew the naturalists would die for a photo and I did have my little Rollei with me, but it didn’t have a very long lens. I was 75 feet away. So I started to walk slowly toward the cat. We never took our eyes off each other as I steadily closed the gap between us. Her expression never changed…she looked bored, maybe slightly amused. I continued to move in. 40 feet, 30 feet, 15 feet…

Rrrrm.

It was a short “Rrrrmmm,” expelled without much enthusiasm, but it was enough to convince me that this would make an excellent photo point. She posed regally and managed not to jump when the shutter clicked. I retreated once again to the dry wash, picked up my pack and headed downstream. She followed me along the crest of the boulders until she was convinced I was leaving for good, and then turned back into the shadows and disappeared. I never saw her again.

Another cat story.

Four years later, my friend Annjanette and I were descending into a canyon in a remote area just beyond the park boundary. With us was my dog Squawker, who, by her sheer presence, was in blatant violation of the Code of Federal Regulations, Volume 36, Section 2 something or other. As a ranger it was my duty to issue her a citation, but I didn’t. I avoided being a hypocrite by never taking my dogs on the trails (which I believed did create a problem), and by refusing to issue citations to dogs I saw in the backcountry (I never saw any).

We were bushwhacking our way through some dense oak brush, and I thought Squawker was somewhere to our right, doing the same thing. But directly in front of us, less than ten feet away, an animal suddenly and silently emerged from the thicket. I assumed it was Squawker. But it wasn’t. It was a mountain lion.

I believe Annjanette and I both said, simultaneously, “Holy shit,” or something similarly profound. The big cat stepped onto a wide sandstone ledge, turned slowly, and looked directly at us. The muscles in her shoulders rippled with every step.

In that moment, I remembered an incident from just a few weeks earlier. We had gone to a small circus that passed through Moab, and were horrified at the sight of the animals, particularly the mountain lion. Fat and slow-moving, it flinched and cowered every time a human walked near it. The scene was too disgusting to watch and we left 10 minutes after we arrived.

But now. Stories have been told about the remarkable strength of these animals. They have been known to climb trees carrying a deer that weighs as much as they do. I read once that a mountain lion dragged away an 800 pound horse. This remarkable creature was capable of doing all those things. She paused only briefly, then jumped over the edge into another tangle of oak. We emerged from our own thicket, crossed the sandstone shelf, and gazed into the canyon.

There was not a trace of her. Not even a movement in the brush. The entire experience lasted less than ten seconds, and even that was extraordinary. Mountain lions rarely travel during the day and will cover 10 to 20 miles a night in their never-ending search for food, especially deer.

While we stared into the shadows below, I suddenly realized that Squawker was missing. Panicked that the cat had pinched her head off, I started to call her name. Finally she emerged from the oak brush, looking absolutely terrified. “Squawker,” I said, “You could have been that cat’s dinner.” Squawker was always a pretty dumb dog, but this time, I think she understood.

The third cat story.

A year later, I was hiking illegally with my dog again, this time, the other canine, Muckluk, Squawker’s mother. (If I’ve said it once, I’ve said it a thousand times, “You can’t go wrong with a dog…except for those damn Pekinese, because if you get them real upset, their eyes pop out.”)

We were trying to avoid the tourists (even then), and had cut cross country from Willow Flat in a direction we’d never tried before. From the dirt road, we crossed a black brush meadow, but soon found ourselves in the head of a drainage that eventually reached Courthouse Wash, several miles away. Muck had exited the wash on my left, in search of some poor helpless rodent to harass. But a split second later, she seemed to be charging right at me from the other side of the drainage. But it wasn’t Muck, it was a coyote. This wild canine came within 30 feet of me, stopped, and started to bark at me. Muck came back and the coyote barked at both of us. Muckluk barked back, and I would have too, if I thought it would have served any purpose. In a moment, another coyote appeared, also barking. And then another. And another.

In a span of a minute or two, we were surrounded by six coyotes, all of them howling and yipping and barking like crazed loonies, or certain members of my own family. What was the deal? Had they mistaken me for the full moon? Were they in love with my dog? Were they part of the choir? I realized that I had disrupted something, and as a result, they were very upset to the verge of hysteria.

I began to look around me for clues, along the wash bottom, and on the edges of it. It didn’t take long to solve the mystery. Beneath a juniper tree, 30 feet downstream, I found a cat. Not a bobcat. Not a lion. But a small black and white domestic house cat, complete with a collar, a frayed blue tether, and killed so recently that it was still oozing blood. Somehow, this cat with bad karma must have broken loose from its owners, probably at the Balanced Rock picnic area, and had wandered away, never to return. Who knows how long it had been out there, before meeting its end at the hands of a bunch of hungry coyotes? I had interrupted their dinner.

There was nothing to do but let them eat. This unfortunate little kitty had become a part of the natural scheme of things. She had probably consumed her share of kangaroo rats and whiptail lizards, before the feline predator became the prey.

Muck and I left them to their meal. When we passed by there again, several hours later, I followed their tracks for awhile. I could see where the pack had taken their victim to a place where they could eat in peace. This time they were adamant…no more interruptions. The cat was at peace as well.

* * *

Living at the Devils Garden was like nothing I ever experienced, before or since. Despite the hordes of tourists and the rumble of engines, there was a peace and a tranquility that comes with that kind of protected space. On many nights, when the campground had quieted down and I wandered into the night, I had the sensation of being a parent who had put his kids to bed, and who could now relax and enjoy the the rest of the evening.

The critters and I endured all the craziness of the park and its temporary human inhabitants and managed to co-exist. In fact, it was more than that—they were my neighbors. And, of course, even I was a visitor. But they tolerated me more than I deserved. In trade, I tried to protect them as best I could.

NEXT TIME: There are more critter tales to tell…

George the Raven, who almost pooped on James Watt. The Great Horned Owls who loved tamarisk, the Gopher Snake that tried to bite my nose off. Those dastardly Brown-headed Cowbirds. The Black Bear that I thought was a dog. The Desert Bighorn who kicked a tourist’s ass…and more

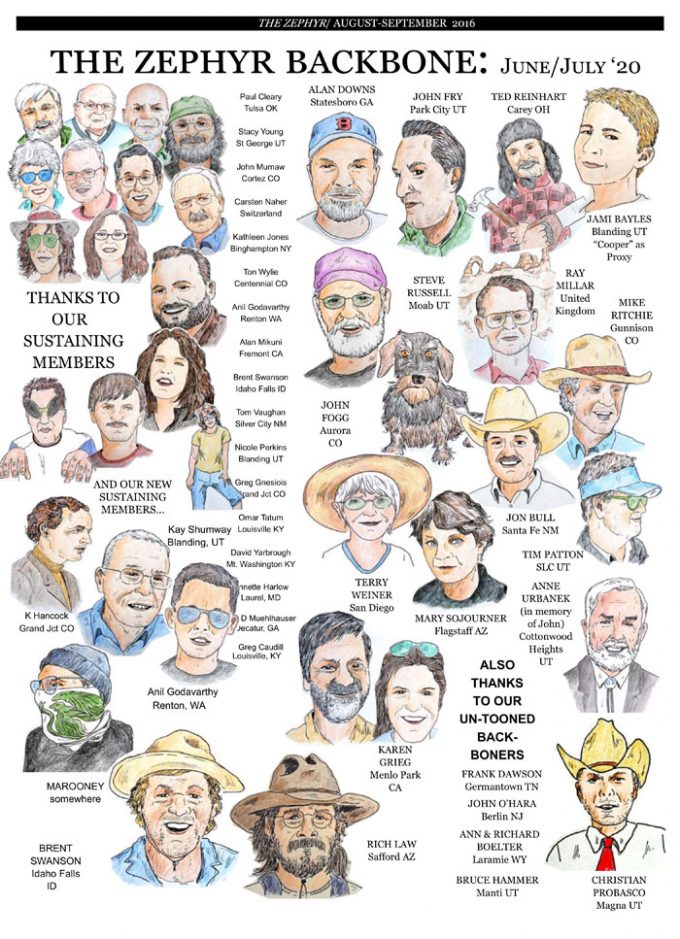

Jim Stiles is Founding Publisher and Senior Editor of the Canyon Country Zephyr.

Click Here to read the previous installments of Ranger Stiles’ Wildlife Observation Notes…

To comment, scroll to the bottom of the page.

Zephyr Policy: REAL NAMES ONLY on Comments!

Don’t forget the Zephyr ads! All links are hot!

I love the ‘critter’ stories. Keep them coming! The Mountain Lion is my favorite animal (along with the wolf) even though I’ve never seen one in the wild.But I did get up close and personal with a friendly Raven who walked up the wooden steps with me at the Windows. And I’m pretty sure it was the same raven that came near me as I was eating my lunch on a boulder overlooking the valley on that little trail behind the Windows. I’d sure like ti sit on that boulder one more time!