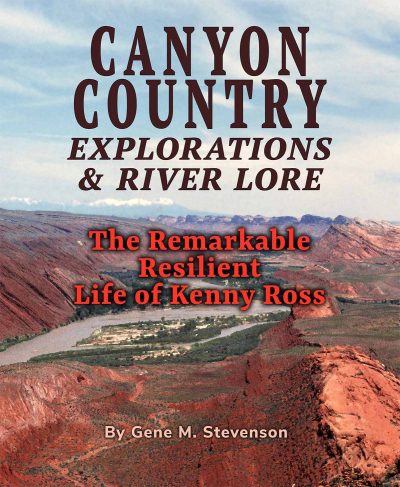

The following excerpt is from the book: CANYON COUNTRY EXPLORATIONS & RIVER LORE: The Remarkable Resilient Life of Kenny Ross, by Gene M. Stevenson. The book was written about Kenny Ross, one of the forgotten personalities on the Colorado Plateau whose major influence on river running in the Southwest had been previously overlooked.

Most all the rivers in the western USA have names for rapids that are large enough or technical enough to be of concern to river runners. The name can be based on river mileage (RM) above or below a certain geographical point (e.g., RM 305), or it can be based on the amount of drop across the rapid (e.g., Thirteen Foot), or it can be named after some geographical point (e.g., Dark Canyon), or someone’s name (e.g., Ross), or based on degree of difficulty (e.g., SOB). So, there’s usually a story behind why or how a particular rapid got its name.

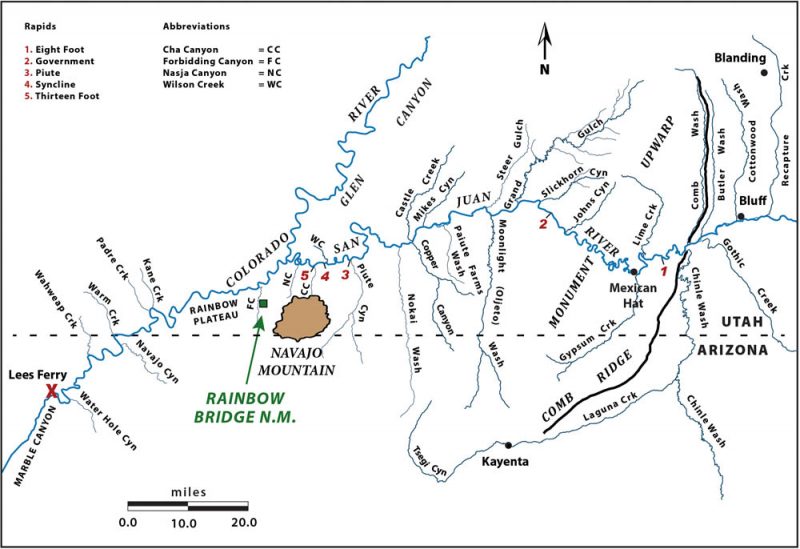

This story is about how Government Rapid on the San Juan River isn’t just misnamed, it’s in the wrong place! The name is based on a supposed boat accident that occurred during the 1921 USGS Trimble Survey of the river. We know it is located somewhere downstream of the Goosenecks portion of the river canyons and upstream of Slickhorn Canyon, but where exactly remained a question in 1956 when Otis “Dock” Marston asked Kenny Ross – “where exactly is Government Rapid?”

Kenny didn’t answer Marston because, quite frankly, I don’t think Kenny had given it any thought, but I have. Based on river miles, the real Government Rapid lies miles upstream of what is erroneously called Government Rapid. How did this screw up happen? Should Government Rapid be properly assigned to the real location? And if so, then shouldn’t there be a petition to change the name of the wrongly named rapid to something more appropriate? It’s a treacherous enough rapid that deserves recognition, but what name then? To answer these questions, a little background information is necessary for this river tale to be told.

Background

Kenny Ross first ran the San Juan River in 1933 on the same trip with Norman Nevills. Both of them were novice’s and were listed as “boat crew” on the very first scientific expeditionary river trip down the San Juan River under the auspices of the Rainbow Bridge-Monument Valley Expeditions. The initial RBMV-sponsored river trip launched from Mexican Hat in several Wilson fold flat boats and got off the river at Lees Ferry – a distance of approximately 193 river miles. Unfortunately, notes from that trip and the following year’s trips were lost in a house fire, so we have no documentation of any mention of a “Government Rapid” from that maiden RBMV voyage in 1933, and Kenny didn’t recall any mention of it either.

Over the next two decades, Kenny Ross worked away from the San Juan River, and didn’t return to boating the San Juan until 1947, and he didn’t boat the sheer-walled limestone canyon stretch below Mexican Hat until 1950. However, by 1936 Norman Nevills had gained notoriety as a dare devil river sportsman, and had developed quite a popular following. He was in full river runner mode with his “Mexican Hat Expeditions” river company.

Then on Friday May 27, 1949 Kenny landed his boating group at Mexican Hat and saw Norm rigging a trip that would leave the next day. He hadn’t seen Norm since 1933. That evening, Norm and Kenny sat and discussed running the river and what the rapids were like in the canyon below the bridge and if there had been any major changes or new rapids. Kenny quizzed Norman pretty strongly that evening and the following morning at the lodge. It had been sixteen years since Kenny had seen the stretch through the limestone canyons down to Slickhorn Canyon and past the confluence to Lees Ferry in the fold flat boats used in the RBMV trips. Kenny was now the Director of the Explorers Camp for boys and was planning two trips for the upcoming season. The plan was to launch from Bluff and run all the way to Lees Ferry – some 225 miles downriver and he wanted to make sure of his itinerary.

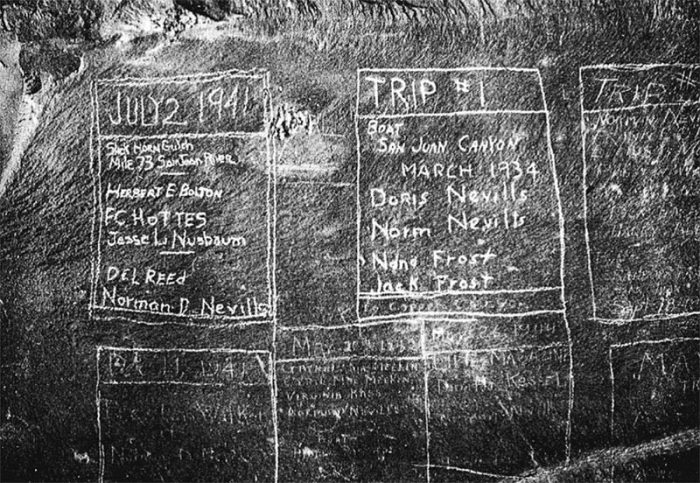

By May, 1949 Norm Nevills was perhaps the best known – if not famous – river personality operating in the western U.S. He had been filmed running rapids and had taken many folks down the San Juan as well as Grand Canyon and other rivers. As was the trend in the early years of river boating, carving, etching or painting your name and the names of others in your group on a rock wall or alcove was common practice and most typically at the head of rapids or where some sort of boating incident had occurred.

Nevills seemed to have not missed a trip where he listed his groups’ names down the San Juan River below Mexican Hat. As documented by the inscriptions listed on several registers beneath an overhanging ledge of massive limestone at the downstream side to the stair-step entrance into Slickhorn Canyon (RR @ RM 74.4 miles above the confluence with the Colorado River) Norman had made at least twenty-plus trips by 1946. The slab of limestone overhead protected the list of names Nevills and other river runners had made and constituted an important history of the trips made by Norman Nevills although he ran trips on the San Juan right up to his death in 1949.

The names were later recorded and published in 1964 by Greg Crampton but as he said, not all names could be deciphered and there may have been some mistakes in spelling. But proof of that first trip with Doris Nevills and Jack & Nana Frost was etched into a cliff face near the entrance into Slickhorn Canyon by Norm Nevills that says “March, 1934” with their names listed below.

Many additional names were added that Crampton missed, including those by Kenny Ross, Doug Ross and Don Ross but over the winter of 1985-86 the massive overhanging limestone slab collapsed and broke into a rubble pile of angular blocks and buried those many names. However, Doug Ross’s name and a few others were saved as they were inscribed on a lower ledge and remain visible.

The last known inscription by Nevills was a trip run in June, 1946, and one of his very last trips down the San Juan was the trip that launched the day that Kenny and his entourage headed back to Colorado (May 28, 1949). His untimely airplane crash with his wife Doris aboard on September 18, 1949 marked the end of the Nevills era. Thus, it was somewhat fortuitous that he met with Kenny on May 27 and discussed boating down the San Juan River through Glen Canyon and possibly even Cataract Canyon.

Norm Nevills was certainly the pioneer to first run commercial river trips on the San Juan and through Glen Canyon, and by 1949 he had created his own competition. Yet Norm or most of his competitors showed little to no interest in the upper canyon of the San Juan or the flat water stretch above Bluff back towards the Four Corners. This may have been due as much to the problem with roads, or the lack thereof, which added days onto any trips organized out of Mexican Hat. Nevertheless, Nevills demonstrated little interest in the archaeological history that was amassed in the numerous sites and petroglyphs upstream or down, including Grand Gulch.

He appeared to have been most interested in seeing how fast he could make it from Mexican Hat to Slickhorn, a distance of some thirty-nine river miles, or to show-off “facing the danger” of running rapids for the movie cameras. Many of the inscriptions noted the number of days, or hours it took to make the run from Mexican Hat to Slickhorn with the “New Record” of five and one-half hours noted for June 1, 1942 in his favorite boat, the Hidden Passage. Of all the trips down the San Juan, Norm was only known to have shown interest in the rapids and didn’t seem particularly interested in slowing down to hike Honaker Trail or to examine any geological features or examine fossils (of which there are many) along the way. Norm was also a noted camp entertainer and spun many river stories or did stunts for an eager audience of onlookers. But to get to Slickhorn or farther downriver, he had to run a rapid located about three miles upstream that has become known as “Government Rapid.” But who named it?

The Dock Marston Letters 1956

A late 1956 letter from Dock Marston to Kenny commented on this very subject that requires explanation. Dock’s key comment pertained to Government Rapid on the San Juan River:

And I also enclose print of the repair work on the government boat which cracked in a rapid above Slickhorn. All you need to do is to identify the spot and we will have the right location for GOVERNMENT RAPID.

WHERE IS GOVERNMENT RAPID?

Present day river runners who have been down the San Juan River from Mexican Hat to Clay Hills landing know about Government Rapid; or they think they do. It’s one of the five most difficult rapids to run for the entire length from Bluff to the confluence with the Colorado River and the most worrisome rapid to negotiate by present day river runners, particularly in low water (under 600 cfs). Most modern-day river logs show river mileage (RM) 0.0 running downstream that begin in the vicinity of the present-day concrete ramp at Sand Island, west of Bluff, or the U.S. Highway 191 Bridge crossing a half-mile farther downstream. So right away, there’s a half mile or discrepancy when downstream measurements start from arbitrary man-made points that can be washed away by floods.

This discrepancy immediately created some confusion when referring to points downstream. When the San Juan and Colorado rivers were surveyed in the 1920s, the zero points (0.0 miles) were at confluences and mileages were measured upstream. Even though the confluence of the San Juan and Colorado rivers are submerged under Powell reservoir, the zero point is still present and shown on USGS topographic maps and was very much present as a confluence of the two rivers when the Kelley Trimble Survey was conducted on the San Juan River in 1921.

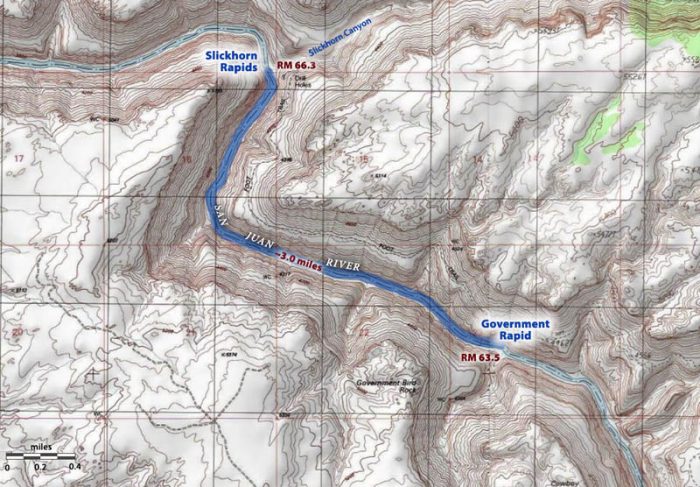

Modern day river logs show Government Rapid somewhere near RM 63.5 downstream of Sand Island, or the bridge. Hugh Miser, geologist on the Trimble Survey party of 1921, noted that this rapid occurred about three miles upstream of the mouth of Slickhorn Gulch (RM 66.3) which, by my measurement is 77.2 miles above the confluence. Gregory Crampton noted many San Juan Canyon Historical Sites in 1964, including Government Rapid: “This is a short sharp rapid at mile 77.6 caused by big sandstone blocks near the right bank.”

Although sandstone boulders are present, most of the boulders in the rapid are actually comprised of large angular blocks of dense cherty limestone containing marine invertebrate mega-fossils. The boulder strewn constriction is due primarily to a boulder fan derived from a small steep canyon on river left (RL); not the “right bank” (RR) as mentioned by Crampton. Plus, dense cherty limestones erode much more slowly than do sandstones. In low water this rapid is quite the technical boulder field to negotiate, but in water levels of 1200 cfs or greater it is a big wavy, bumpy ride that can be run right down the middle like Bert Loper’s run as shown in the 1921 photo by Robert N. Allen.

Hugh Miser was still alive in 1963 and he told Greg Crampton on November 5, 1963 that the name came from the rumor that a government boat was wrecked there. Miser was referring to the U. S. Geological Survey party of 1921, of which he was a member that mapped the canyon in cooperation with the Southern California Edison Company of Los Angeles. “No boats were lost there, he said.”

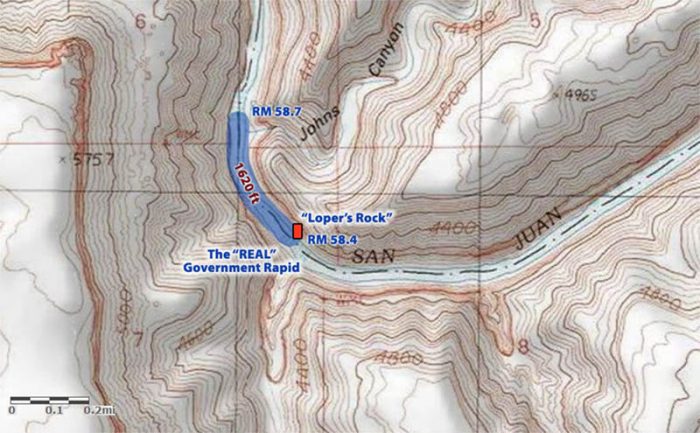

The boats of the Trimble expedition were run through most of the rapids. In shooting the worst ones Loper, the boatman, was the only member of the party to stay in the boats; the other men walked along the banks around such rapids. The loaded boats were nosed one at a time through a few rapids by the boatman, who in wading held on to the bow and guided it downstream ahead of him. The equipment was portaged around a rapid 3 miles above the mouth of Slickhorn Gulch, and then the boats were run empty through the rapid. [Author’s note: This is Government Rapid and no mention of any boat damage here] The loaded boats were run through a small rapid half a mile above the mouth of Johns Canyon, but one of the boats containing two members of the party not only narrowly missed striking the canyon wall but struck a boulder and was burst on one side from bow to stern. The boat was nearly filled with water by the time a landing place was reached. Then the wet equipment was unloaded, and the boat was dragged ashore and repaired.

Therefore, the government boat referred to above that was badly damaged occurred about 1620 ft (0.3 miles) above Johns Canyon (RM 58.7 on modern logs measured downstream from the Highway Bridge datum point). In high water at about RM 58.3 there is a small riffle with sand waves, but at low water it is necessary to sneak along a sheer wall on far river right (RR), staying right of an emergent cobble bar, then pull hard left to miss a huge boulder on RR at the bottom (RM 58.4). This was where the 1921 government boat hit “Loper’s Rock” and was damaged – and NOT the rapid roughly three miles above Slickhorn Gulch! But the boatman, Bert Loper, who was rowing the boat on that 1921 incident had a slightly different take about how badly damaged the boat was and provided more details that led up to the accident. He also firmly defined that the accident did not occur at what is popularly known as “Government Rapid.” It is also informative as to how the boatman considered the damage as minor, while the passenger saw the damage as catastrophic!

The following account was originally typed by Bert Loper, apparently working from his original notes. Brad Dimock deciphered and retyped Loper’s notes from his diaries. Dimock graciously provided me his entire collection of retyped notes when he learned of my plans to write this book about Kenny Ross and the San Juan River.

August 5 – I ferried Elwyn across the river the first thing on starting out and it was soon after that a mountain sheep broke back up the river past him it had become rimmed so it had to get back up the river—I had to ferry the main bunch across the river on account of the being rimmed and in crossing we ran into some sand waves and one of the bed rolls was thrown out of the boat but was recovered then we had a rapid to go over and one of the row locks broke and things looked rather serious and in fact we did strike a rock and the boat was split rather bad but we landed and took the boat out and it was soon repaired—it was a rather unwieldly outfit to handle any way for I had two boats with two men in each boat but the accident was not so serious—by the time the boat was fixed it was noon so we had lunch and this was at the mouth of Johns Canyon and at the mouth where the canyon pours over there is about a 60 foot drop so there was a basin of clear water so the boys had a swim in the clear water—In p.m. we continued on our way and had good going but some very swift water—had a very good camp, for the night.

Aug 6 – saw us on our way good and early—I took Trimble, Allen, Hebe in one boat and Elwyn took Miser and Hugh in the other and we drifted down to the head of a rather severe rapid—the river is very narrow and swift—In p.m. we came to where we had to portage the loads but I ran the boats through—Elwyn saw another Mountain sheep. Mr. Miser found a perfect piece of pottery— we reached the mouth of Slick Horn Canyon and made camp and will have to wait for Wesley Oliver with the supplies—In 1894 this was the camp of Bill and John Clark and Al Rogers they placered out a small bar just above the mouth of the Canyon.

Thus, the rapid located approximately three miles above the mouth of Slickhorn Canyon almost certainly was mis-identified, but by whom? My research has not come up with a definitive answer, but I suspect that it was none other than Norman Nevills who began calling this rather severe rapid “Government Rapid” at some point after March, 1935 and the name stuck. He made numerous runs (at least 20) down the river typically launching at Mexican Hat and almost made a race out of it to see how fast he could make it to Slickhorn where he and his groups left their signatures and later catalogued by river historian, Greg Crampton. Norm made little mention of the rapid, or much else along the way, but he ran it enough times and at different flow rates that he saw it was a rapid to pay attention to and most likely gave it the name.

Randall Henderson, editor of Desert Magazine wrote an article in 1945 about his experience boating with Norm Nevills on the San Juan River and Government Rapid was mentioned (the rapid about three miles above Slickhorn Gulch), and Wallace Stegner recalled his trip with Norm Nevills in 1947 where he also mentions running Government Rapid.

Except, no government boats were damaged at this rapid in 1921!

Kenny Ross made his second full run of the SJ&C (San Juan & Glen Canyon) in his inflatable LCRs in 1951 and he described the rapid and their run of all the fully loaded boats through “Government Rapid” as the “big, black, hairy one.” But he didn’t have any upset or damage. He had seen this section of the river the previous year and then nearly seventeen years prior when on the 1933 RBMV trip where they more than likely lined and portaged the foldboats as every twist and turn in the river was new. But one thing is for sure – the USGS survey group in 1921 did not give this rapid its name.

Regardless of who named it, all of us who followed – right up to modern day river runners relying on modern day river guide maps, as well as the most recent USGS topographical maps continue to carry this mis-named rapid as Government! Fittingly, the San Juan River cuts across the Paradox Basin. How appropriate to have a most paradoxically named rapid.

And wouldn’t it be nice to name something on the San Juan River after Bert Loper, the lead boatman on that 1921 USGS trip? I think that small riffle above John’s Canyon should be named “Loper Rapid” since it was here that all the commotion began about something that happened to a government boat in 1921. See how things get all screwed up in the telling of river lore!

To comment, scroll to the bottom of the page.

Zephyr policy: REAL NAMES ONLY on Comments!

Don’t forget the Zephyr ads! All links are hot!

Your reasoning makes sense, Gene.