What’s the biggest mistake you ever made?

No, not that kind; I mean work related. If you’ve reached A Certain Age, you might even have trouble picking the one. Not me; mine shines out like a beacon against the busy background of a career in this business—both practicing it and teaching it.

Considering your work mistake, how many people knew about it? The boss, for sure, or other supervisor, customers involved, possibly, bystanders, perhaps—not a huge number. In journalism, everyone knows; the mass audience may run into the thousands, as, say, in a community newspaper. Plus, you are ethically required and honor-bound to apologize in the following issue with a correction or retraction (There’s a difference), in as prominent a location as the error, just to stick the knife into the reporter’s psyche a little deeper.

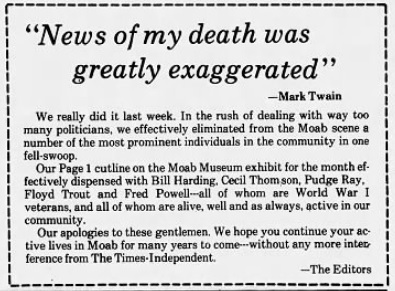

Corrections are generally easier; they involve a simple misstatement of facts: The city council hearing will be at 7:30 p.m. Whoops, no, the meeting started at 8. Not Earth shattering, just annoying, especially to the council members and those who were planning to attend. Retractions are different; they have legal ramifications. The publication has damaged someone’s reputation, and a retraction attempts to undo the damage. A timely one can even eliminate a libel suit in some states (A bit of advice: Libel laws apply to the internet, so exercise care with your comments.). This tale involves a correction, which, for the reporter, was anything but simple, although looking back at the offending piece, a photo caption, and the following correction, I remember the whole episode with a stab of remorse.

I told this story twice a semester (one for each section of the intro class) throughout my years as a college journalism prof; it was too perfect not to do so. I used it as an ideal, if painful, cautionary tale for prospective reporters that, even with the best of intentions, under deadline pressure you can screw up monumentally, hurting people you have never met and damaging your professional reputation. The telling embarrassed me every single time. And this will be the last.

The hoary old cliché “It started out innocently enough” screams to be used here, but I won’t. You’re welcome.

Wednesday, October 29, 1980, was a production day, and we had no art for above the fold on the front page, although the shot of broadcaster Les Erbes getting an award on the lower left might have sufficed. However, in those days, changing a paste-up involved a good deal of time and labor, and nothing, positively nothing, delayed the printing of the paper, because copies had to be at the post office Wednesday afternoon by a certain hour (which I don’t happen to remember, but somewhere in the late afternoon) or the paper wouldn’t be in mailboxes Thursday morning, which was unthinkable.

To give you an idea of how absolute journalism deadlines are, one of my former students, a sportswriter at the local Stockton, Calif. daily, commented once that if a reporter blew the 11 p.m. deadline by even a second, the next night the deadline was 10 p.m. If you ever did it again, the deadline was pushed back to 9, and if you blew that one, you were fired, and that policy was generous by industry standards.

At any rate, we needed a photo, which would take an hour to process at my best darkroom speed, including developing and drying the film, making a print, drying that, and converting the print to a halftone. What I would have given to have instant digital processing, had it existed. At the time, however, digital photography and computer paste-up were years off.

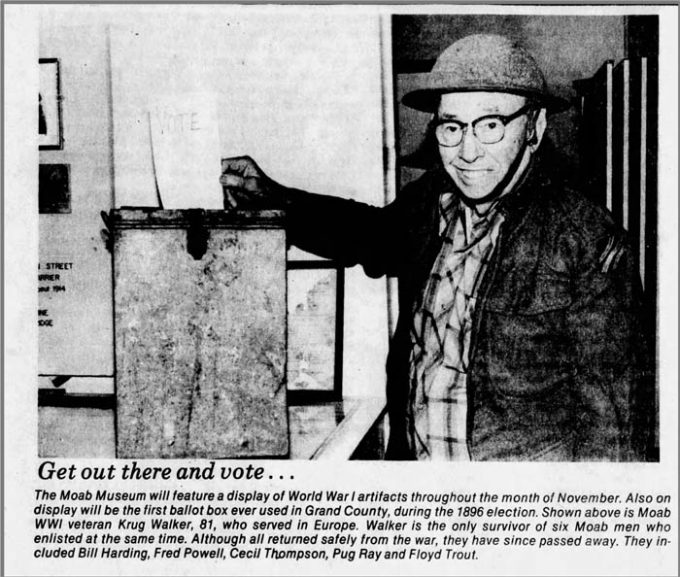

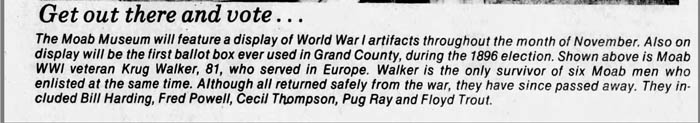

Then the Moab Museum called with my salvation: They had just installed an exhibit of World War One memorabilia for the upcoming Veterans’ Day, and had a real-live WWI veteran dressed in his uniform (As I was to discover, there were still a number of them alive at that time). They also had Grand County’s first-ever ballot box. Would I like to take a picture of the uniformed vet inserting a ballot to remind people to vote in the upcoming special election and honor veterans on Nov. 11? You bet (a bit cheesy it’s true, but this constituted front-page art for a community newspaper with a desperate reporter/photographer.).

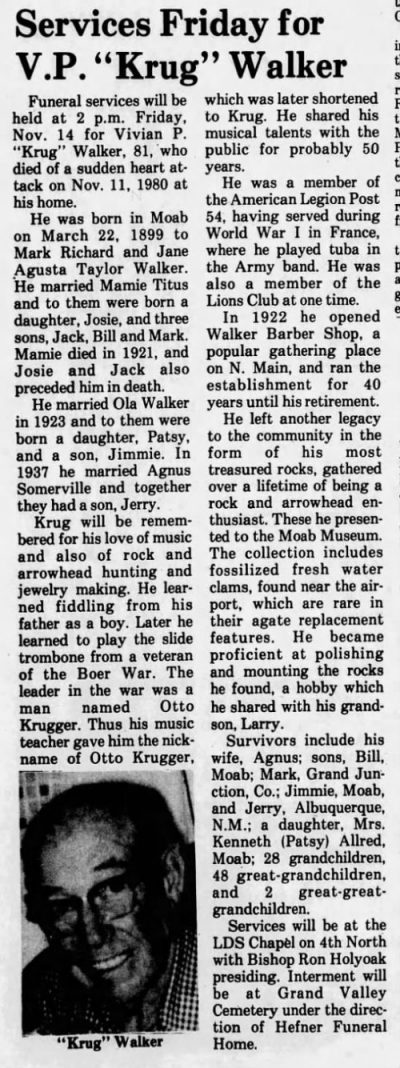

I hustled up there (on foot, another thing I liked about living in a small town) and was introduced to Vivian P. “Krug” Walker, 81, a slight, friendly fellow who could still fit into his Army uniform from The Great War.

One of the other rules of journalism is “Thou shalt not run a photo without a caption, and identification of people in the shot.” So I interviewed Krug briefly, as time was extremely short.

Krug, who I later learned, was also an accomplished musician, had served in France, where he played tuba in the Army band. When he returned to town, he operated a barbershop for 40 years, was a popular fiddler and an avid rockhound. It seemed everyone in town knew about him—except me.

During the interview, Krug mentioned that he had enlisted with five other Moab men who had since passed away, and started listing names, stopping after five. I assumed he was listing the guys he went to war with. He wasn’t.

Krug was also, I learned way later, like last week, the father of County Commissioner Jimmie Walker, with whom I disagreed about pretty much everything except we both loved Moab. I knew none of this at the time I was taking the picture; I was in too much of a rush. Old guy, Army uniform, WWI, other guys dead: Got it.

I dashed back to the office and started processing the film as fast as I could: develop, print, halftone through the hated PMT machine. Oh yeah, caption. Run back up to the front to my typewriter (Younger readers may not know what that is; look it up.). Old vet, uniform, vote, dead guys: Done. Hand the copy to typesetter Cherl Merz. Back to the darkroom to shoot page negatives

Another “rule” of local newspaperdom is “Use lots of names.” So I had in the caption: Here’s the lone survivor of a group of six Moab men who went to World War I, and here are the five who are no longer with us. The last inclusion proved to be unfortunate.

Also proving unfortunate was the fact that Editor/Publisher Sam Taylor had grown to trust me too much. I was reliable in my writing, so my copy didn’t always get the prior-to-publication examination it could have.

The standard at big papers, at least during my era, was at least three readings before publication: copy editor, section editor, and editor-just-below-the-editor-in-chief (titles vary for this position).

The copy editor, in particular, is charged with correcting spelling style or grammatical errors (along with yelling at the offending reporter not to do it again), and keeping the paper out of legal trouble, such as libel.

On small papers, this three-level approach is an impossible luxury. In fact, on some little papers, the editorial staff is frequently one overworked writer/editor/owner. We were somewhere in between. Sam was editor, wife Adrien was managing editor and I was news editor, which meant I was in charge of the entire reporting staff—me.

It sounded good on paper, but on the Wednesday production days, we all had multiple “gotta be done right now” functions that had nothing to do with editing copy. Sam, as usual, was pasting up the pages and waiting for that front-page photo. I was the only person who read the copy, checking the spelling of the names against my scribbled notes.

Cherl’s job was to set the copy on the primitive cold-type unit then becoming common that replaced the ancient Linotype hot-metal machine clanking for decades in the backshop. One thing I knew from experience is typesetters don’t read copy. The only way to type reliably and rapidly (125 words a minute was typical) is to disconnect your brain and hook your eyes directly to your fingers; no comprehension could be involved. She wouldn’t be reading the caption either.

So, bang, bang, bang, here’s the photo, here’s the caption, slap it on the page and back to the darkroom to shoot the page negatives, burn the printing plates and turn them over to production manager Ron Drake, who fired up the two-unit Goss press which could produce one eight-page section at a time (That press, by the way, was previously owned by the radical Berkeley Barb, which I thought was exceedingly cool). In addition to everything else, I also “flew” for the press, gathering up the sections as they came off the folder and putting them into a rolling rack, reversing the sections every 25 copies.

Everyone in the office, and a crew of high school students, participated in stuffing the sections together, a process of which almost no reader is aware. Every single section of every single paper was inserted by hand—the entire multi-thousand press run. I always figured I would have “made it” in the business when I didn’t have to insert papers any longer. No such luck. Even after grad school and landing a job requiring a master’s degree, I was still inserting papers with my students as a community college professor/adviser 20 years later.

There was always a feeling of satisfaction—and relief—watching the issue go out the door to the post office across the back parking lot. The pressure was suddenly off—for that day—following which the weekly buildup would start again. At the end of a long, tough production day, we generally each grabbed a copy and looked at the result of all that work.

Office manager Dorothy Anderson, a Moab native who knew practically everyone in town, was first to notice.

“Hey,” she said, indicating the front-page photo of Krug and its caption, “I know some of these guys and they’re not dead.”

It took a second to sink in. What?

Sam, who knew every single body in the community, examined the caption.

“I know all these guys,” he said, “and they’re all alive, and all of them still live in town.”

My heart dropped through the floor and I felt sick. What, oh god, have I done? And more importantly, how the hell did I do it?

“But he said there were five guys he went to war with, and gave me five names. . .” I began to protest.

What had apparently happened was Krug had shifted gears mid-explanation and listed other Moab guys who had gone to war, guys who were still around. It was my bad luck he stopped at five names. If it had been four, or seven, I would have asked about it.

I already knew the answer, but I had to ask.

“Is there any way we can reprint the paper?”

“No,” Sam said, “Too expensive. We’ll just run a correction next week.”

Still heartsick, I grabbed the phone on my desk. “I’ve got to call all these guys before they see the paper tomorrow and drop dead of heart attacks.”

I got lucky in the midst of a very unlucky day and found all of my victims at home by that evening.

The script went the same with each: “Hi, this is Bill Davis from The Times. Tomorrow’s paper is going to say you’re dead on the front page and I know you’re not, and you’re talking to the idiot who did it, and I’m really, really sorry. We’ll run a correction next week.”

All the vets were sweet as could be, some indicating puzzlement, all thought the whole thing was funny.

Their friends and family, however, did not.

The next morning, after I endured a mostly sleep-free night knowing what was coming, the phone calls started. Each was referred to me, which seemed only fair. I won’t attempt to recreate them, but all were unpleasant, and the majority made some reference to stupidity. This went on for the whole week, until the next issue, when Sam’s correction ran. One particularly crabby citizen even yelled at me from his pickup truck (I heard the word “asshole” as he passed) as I was trudging up the street to the Courthouse (I did a lot of trudging that week.). I couldn’t even yell back, as he, and everyone else, was right.

Sam’s correction, which made light-hearted reference to Sam Clemen’s remark about rumors of his death being exaggerated, ran on the front page of the Nov. 6 issue. My mood sank lower into the depressive swamp, and I seriously considered resigning. My job was to ensure that accurate information appeared in the paper, and I had blown it.

There was worse to come. Much of our press run went to subscribers outside the area, who received their mailed editions up to a week or 10 days after publication. That meant I had a whole new flock of complaints throughout the week from relatives who “didn’t know Grampa/Greatgrampa had died, so I called all upset and he’s fine, and how could you do this to me/us?” And I had no real explanation.

Yet the Cosmos wasn’t done with me yet. After a week of dealing with the out-of-town complaints, I was slumped at my desk on yet another production day, Nov. 11, 1980, mentally banging my head on the typewriter for being nine kinds of an idiot, when a call came in on the scanner for a heart attack at an address that had become all too familiar.

I was batting 1,000: The five vets I said were dead were alive, and Krug Walker, the one vet I said was alive, and had a photo to prove it, died—on Veterans’ Day.

.

Author’s note: After all of the above, for a solid month, each production day afternoon at 3 p.m., I received a phone call featuring the same aged voice:

“Hello young fella? I’m still alive! Hee, hee, hee, hee!” Click.

I never found out which of the vets it was.

Author’s note, the second: The whole sorry episode can be seen in the late-October to mid-November, 1980, issues of The Times-Independent on the University of Utah’s Marriott Library Utah Newspapers Collection: the caption, the correction, Krug’s obit, and Sam’s column memorializing their long friendship; it all appears pretty mundane to the casual reader. I’d rather you didn’t.

Author’s note, the third: To salvage something educational from the story: There were no legal issues involved in my killing of the vets. The Supreme Court decided many years ago being dead didn’t injure your reputation. The knowledge didn’t help much.

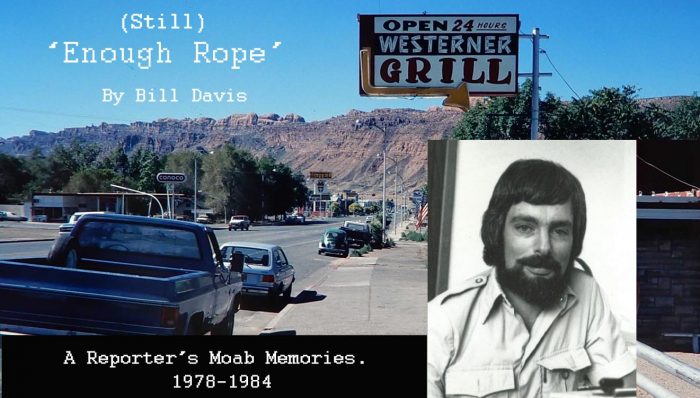

Los Angeles-born BILL DAVIS first came to Utah as a student, where he earned his Bachelor’s degree in Journalism from Utah State University. He spent his wayward youth working as a graphic cameraman and photographer, then as a musician. In 1978, Bill was hired as a reporter/columnist for Moab’s Times-Independent Newspaper before returning to USU with his wife Kris and gaining his Masters Degree. He taught Journalism at San Joaquin Delta College in Stockton, CA for 24 years, until his retirement in 2010. Now he and Kris live in Salt Lake City, UT.

To comment, scroll to the bottom of the page.

Zephyr Policy: REAL NAMES ONLY on Comments!

Don’t forget the Zephyr ads! All links are hot!

oh, ho,ho: one domino falls, hits another, and …

yeah: fun(ny) story — well after the fact !