This article first appeared in the November 1989 Zephyr…

No doubt, when traveling, you have stopped for a passing freight train. Chances are, on one or more of those occasions, you have seen someone riding on a car. What crossed your mind? Perhaps you thought, why doesn’t that person get a job, buy a car, get insurance, like the rest of us? On the other hand did you think, how romantic, I wish I could do that?

Trains have fascinated us since the days when coal or wood-tendered steam locomotives moved along that great linear city, dragging us by the carload into the twentieth century.

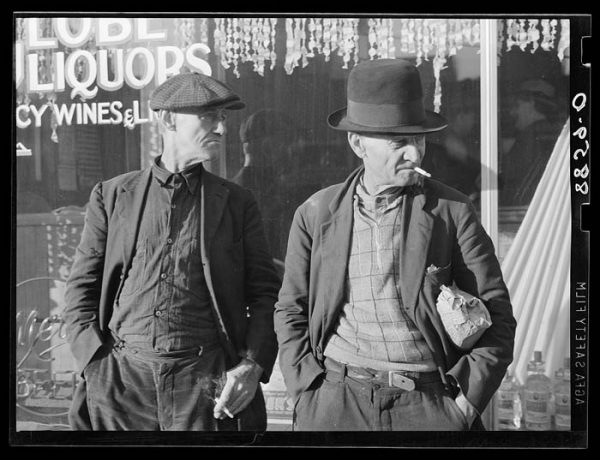

It was probably this country’s Great Depression and the Dust Bowl era that brought bumming the rods into vogue. Migrant workers, following the crops. Tramps doing odd jobs, then riding on to the next town. Hobos.

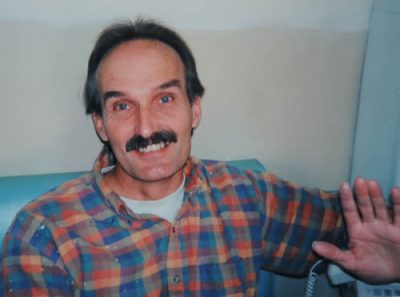

Webster’s New World Dictionary describes hobo in this way: 1. a migratory worker 2. a vagrant; tramp, ho! Beau! Formerly a greeting between vagrants. I had never really thought of myself as a bum or tramp; though I have traveled a bit. And I have been employed as a migrant worker. I have even done odd jobs from coast to coast, to coast (Houston, Texas, the third coast). After spending the better part of a month riding the rails, I’m proud to say, “I’m a tramp.”

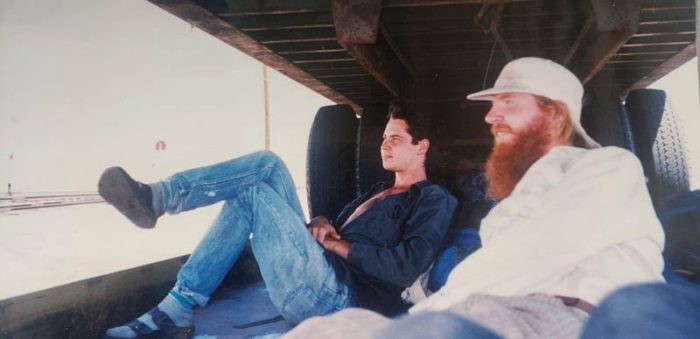

It all started when Hugh Glass (you know the red headed guy who rides the recumbent bike) told me he was going, by rail, to Seattle.

“If I had the time, I’d love to go with you,” I said.

“Why not?”

So I began to think of all the reasons why I shouldn’t go. After listing a dozen reasons why I shouldn’t go, I was convinced I should.

It was not long before we had attracted a third member to our little troupe: David Whidden, (you know, the little poet). So we were off to the Emerald City.

Some of the questions I’ve been asked since my return have been almost as interesting as the trip itself. Questions like, do many people still ride that way? How do you know which train to catch? Is it dangerous? Were there any women? Why did you wait so late in life to do it? How did you prepare for the trip? I must say though, none asked me why I would do such a thing.

It is surprising how many people are still traveling by freight trains. Not far from the Ogden yard, during a siding that lasted several hours, we met Jimbo. A man in his early thirties. He had been in an accident, some years previous, and was on medication to prevent epileptic seizures. I was curious as to how he got started riding freights. He said he was hitch-hiking with some friends. It was too long between rides; he saw a train pulling into a nearby yard and thought that would be faster. He told us how he walked right into the yard as if he owned it. From out of nowhere an elderly man grabbed him and pulled him into the bushes. ‘You can’t do that,” the old man said…”We’ll get thrown out of here.”

“Well, how do you get on one of these things anyway,” Jimbo asked him.

The old man’s reply, as if through the wisdom of the ages, “You just walk on.”

Seymore, a man we met along another siding, had quite a different story to tell. It was difficult to tell his age, but he said he had grown children living in the east. He told of a family reunion coming soon. He was not going. He had nothing and did not want to embarrass the children. In his younger days, he worked hard, paid the mortgage, helped raise the children. Tragically his wife died ten years ago. He walked away from the mortgage; the children were gone already. Seymore hopped a freight and never got off. Just before we met him, he had made about a thousand dollars as a caterer during the recent fires nearby. It seems not far down the line he had hired a female companion for the evening. Unfortunately she had two large friends. He still had the fresh scars on his face, but not his wallet.

There were many others we met along the way. There was a group of about eight men we talked to in the Grand Junction yard. We saw them later in the Salt Lake yard. “Where ya headed?” is the common greeting.

“Seattle.”

“Oh! If you plan on going through Pocatello, watch out for the bulls there. Some of the meanest in the country, especially Shirly.”

As we travelled north, Shirly’s name came up again and again. Jimbo spoke of her—she had thrown him out of the yard at least twice. He was definitely not going through Idaho. He could not bear the thought of being caught a third time.

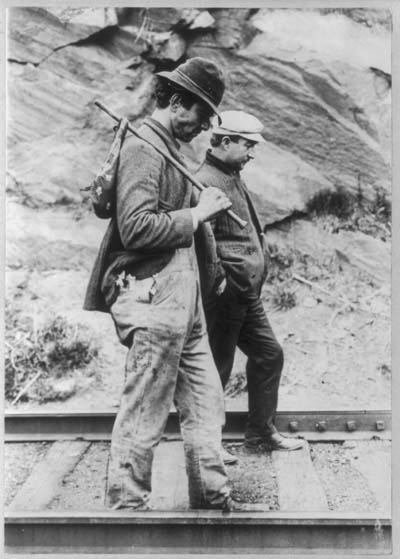

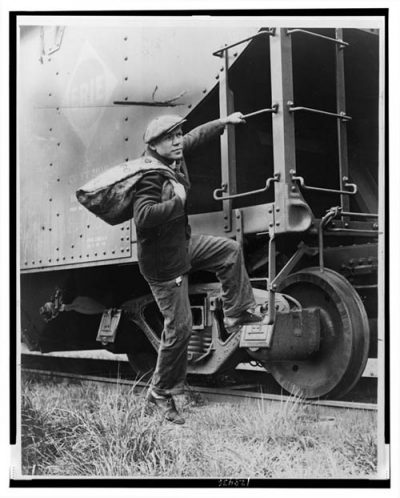

In answer to how to catch a train, the obvious is certainly true. It’s best if it’s standing still, though it is necessary, at times, to catch one on the fly. That was the case in Vancouver, Washington. We had been waiting well over twelve hours. Preparing to do a little rubber tramping, we heard one of the bums say, “You fellas going to Seattle?” Pointing to a hot shot slowly moving through the yard, he said, “well what do you know.” We were off and running.

By the time we could match its speed, we were at the tail end. I saw Hugh sling his mandolin on to a car. That’s it…we were committed. By now, I was at the last car, on a train that had no plans of stopping this side of Seattle. I looked behind me. David was still with us, but it was touch and go. Hugh was settled in and gaining speed. Now I’ve always believed that humans were given a certain amount of intelligence. At least somewhere above the animals. As I closed my eyes, and flat out dove for the last piggyback, that belief came seriously into question; I hit the platform, and riveted myself to a narrow steel rail. After taking mental inventory of body parts, I sat up and looked for David. He was still running, but he had run out of train. We would not see him again until our return to Moab.

There is indeed an art to knowing which train to catch. It helps to have an Iron atlas. Rand McNally puts out (what they call) a handy guide to the rails. It shows all the currently used railways in the country. Consulting this handy guide, a route can be planned. Following that, of course, you need to find the rails and a freight going in the right direction. Sometimes you must first catch one the wrong way. That happened to us on the very first ride.

Hugh and I had taken a shuttle to Hite, for C.F.I. They brought us back through Green River, for a burger at Rays and on to Crescent Junction. This is the embarrassing part; Marian Ottinger was on the shuttle. We said our goodbyes, knowing we would not see them for several weeks. Or so we thought. That evening we slept near the tracks in Thompson; thirty some miles from home. Thompson does not have a yard, but there is siding. There is no reason for anything but Amtrak to stop. For much of the following day, we waited for something to side. So there we were, playing pool in the Silver Grill. Eighteen hours into our adventure, still only thirty minutes from Moab. I went out to see what was moving, and there she was. Marian, waiting to shuttle some folks from an incoming Amtrak. Well, anyone else would have gone back inside, avoiding further embarrassment. Not me!

It was a few hours later, while napping under a small trestle, we heard the low rumble of an approaching freight. This is it! Our first ride. Wait a minute, something is amiss. The only thing to stop in the past twenty hours, and it’s headed east. We’re going north. But then sometimes you gotta get in to get out. It rolled to a stop, we were on, and in short order detrained in Grand Junction. A few hours later, rolling out on a grainer, we were finally headed north. Thankfully I was sleeping as we passed, for the last time, the Thompson station.

In answer to the question of the dangers involved, I recall Hugh’s exact words. “It’s as dangerous as you make it.” Well, I myself have found something as mundane as painting to be quite brutal, at times. Imagine what I could do with something a mile long with that kind of tonnage moving at great speed. The possibilities are unlimited.

As if from the very pages of a handbook for Tramp-along-tours, Hugh carefully guided us through our maiden voyage. Never stand between freight cars, if the train is stopped. For obvious reason. The rail right of way is quite narrow. Appendages are easily lost if dangled beyond certain parameters. Basically Stop, Look, and Listen covers a multitude of sins.

Preparation for such a venture should not be left to chance. The rails can be very unforgiving. Of course the distance travelled will dictate, to a degree, what should be carried along. For our trip a large pack with frame is a must. Clothes for every season, sleeping bag, and wool blanket are at the top of the list. A good part of riding is spent waiting. To expect the unexpected is a good rule of thumb. A hatchet, flashlight, matches, canteen, a drinking cup, pocket knife, and food are also high on that list. Some other items to add a bit of comfort, well worth their weight, are a pad to sleep on and a compact cook stove. David brought along a stove and prepared meals of such extravagance as to cause one tramp to ask if we had a fridge on board. I mean, we had burritos a la boxcar one day, stir fry the next. It was almost decent. By all means, add both an iron atlas and a rubber atlas to that list, and you’re on the right track.

Knowing rail traffic priorities may be helpful. We spent at least three days in an open box car—comfortable, but not very fast. If the car is empty, it’s probably on a very low priority train. The fastest freights are the piggys, and containerized cars. Of course Amtrak will quickly side even a hotshot.

Riding on a trash train for a few days did afford us a little recreation. On more than one stop I picked and ate more than my share of wild blackberries. Somewhere along the Colombia River, we sided to let a south-bounder pass. We were anxious to take a final swim before we crossed the river for the last time. To get to the river we had to cross the rails that the oncoming train was traveling on. It is not advisable to allow a passing train to come between you and your belongings. But after all, the water was there and we could keep our eye on the approaching train. What could be better than this? Soaking in the water, our cares slightly farther away than the half mile or so of rolling steel ahead of us.

You know that feeling of dread that comes over you when your assessment of a situation is off significantly? Let me at this point describe for you what is referred to as an air check. Brakes on a train are much like those on a semi truck. That is, they work on a vacuum system line—every car having brakes. The air brake system runs the train’s entire length. When the engineer is ready to move the train, he releases air to test the brakes. This becomes a very important sound to listen for, knowing that, following that, the train will soon be on its way.

Now here we are, in the water, naked. Everything we own is on a waiting train pointed north. The south-bounder is still bearing down on us, but in sight. Now don’t get ahead of me. The physical distance from the waiting train was insignificant. A stone’s throw. For a stone, nice work if you can get it. I mention that because stones play an important role in this scenario. You see, from the water to the train involved a trek across huge moss-encrusted boulders, a better than slight incline heavily laden with loose, light, fist-sized vulcanized rocks. Then add two slick, hot steel rails, attached to the earth by bulky splinter-ridden wooden beams; and more vulcanized rocks. Another incline, and there’s still the train car to mount.

So back to the water, cares heading down the great Columbia River. Plenty of time. Suddenly that all-too-familiar sound. Thousands of cubic feet of air, at the speed of sound, running carelessly the length of our rolling home. AIR CHECK!!! Cars lunging forward. A nameless, faceless man, holding our immediate pathetic futures in his hands. Picture three barefooted heart attack victims, running the obstacle course detailed earlier. NEVER let a passing train come between you and your gear.

One of the highlights of the trip was watching the lunar eclipse. We were riding in the box car. Both doors full open. There were a few dunnage bags, still inflated, lying about the car. I let half the air out of one and used it for a mattress. From a sinfully comfortable front row seat I saw the moon eclipse. First from one side of the box car, then the other, as our train snaked its way through Idaho.

There is not room to tell all. How we narrowly escaped Shirly in Pocatello. The bull that politely removed us from the Portland yard—basically telling us, gentlemen, don’t get caught. Not the mention the bulldog who caught us on the train north of Dunsmuir, California.

It was on our return trip. Just Hugh and I. On a grainer rolling through a small yard he saw us. He drove along the frontage road that paralleled the tracks. There were a couple of tramps standing by the highway overpass. Just that quick he disappeared in the dust and diesel smoke. It was maybe ten miles down the line the engineer stopped the train to shuffle some cars around. One of the knockers assured us that, even though the car we were riding on would be in a different place, it would still be on the train somewhere. Hugh and I bailed out, as did two other tramps who were on board. Knowing we’d be back on soon, we left our things on the car.

The train was so long that, halfway up, it was blocking cars from crossing the tracks. Like a scene with Moses at the Red Sea, the rail cars split at the crossing, and a man in an official vehicle drove through. It was the bulldog from the last yard back. Hugh and I ran for the junipers and hit the dirt. He walked the length of the train to where the other tramps sat, bewildered by what they just witnessed. After taking down their vital statistics, he continued his search for us.

The train was just an air check away from departure. The bull was on the opposite side of the train from us when it was put back together and ready to go. We were, however, two dozen cars back from where our grainer ended up. On a dead run, we aimed for a familiar car. I remember taking at least one good dive and roll. The others, who had reboarded already, were cheering us on (with extra points for my dive).

Breathlessly back on the train, we were still several cars removed from our goods. Then looking back down the frontage road, he was back! I could not believe my own eyes. This man stopped a moving freight train.

In a moment, amidst the sound of gravel under foot, he grabbed a stair rail, swung around, looked us square in the face and said, “And where are you boys going today?” In a word, Dunsmuir! “Be sure you get off there,” he said and disappeared as quickly as he’d approached.

So somewhere out there, at the next railroad crossing, a place where oft times a mile or more of plain ole human ingenuity parades by carrying you and me into the next century, you will entertain a different thought. I know I will. I’ll wonder how Jimbo is doing. Did Seymore get to visit the kids? But through it all I’ll keep remembering what Hugh said from the very beginning. “You’ll never look at freight trains in quite the same way again.”

He’s right, you know. I won’t. Thank you, Hugh. Thank you, David. See you on the highline…

GLOSSARY

Bumming the rods *same as riding the rails, an older usage

Bull *railroad security guard

Hot shot *high priority train

To catch on the fly *to board a moving freight

Piggy *a flat car carrying a semi-trailer unit

Iron atlas *rail guide

Rubber atlas *road atlas

Dunnage bags *eight mil plastic bags, covered by several layers of paper. Used to secure cargo when inflated.

Highline *the main line. Where there is more than one line, it’s slightly elevated

Knockers *the person who takes the trains apart; uncouples the cars, disconnects the air lines.

Trash train *what I call a low priority train; empty cars

Rubber tramping *travelling on the highway

Siding *where there is more than just the main line. It allows one train to pass another.

Grainer *an enclosed hopper usually carrying grain. There is a large metal platform at each end large enough to ride on.

Tim isn’t the only Knouff to appear in the Z…We’ve featured the photography of his brother Terry (HERE) and his sister Becky (HERE).

To comment, scroll to the bottom of the page.

Zephyr policy: REAL NAMES ONLY on Comments!

Don’t forget the Zephyr ads! All links are hot!

I liked the article. A way of life that is no more, as a lot has changed since 1989:

9-11 was the big one. Heightened security.

Plus, box cars are no longer found on most trains…they have given way to flatbeds for containers.

I rode the rails the entire summer of 1975. One of the best summers of my life. I have friends that still call me ‘Boxcar’.

I would love to be proven wrong, that riding the rails still exists….but I just can’t see how any more. Sad.

Starlight on the rails reminded my 95 year old husband of living in North Las Vegas near the Southern Pacific tracks. A large mesquite forest was between the rails and his house. He and most of the neighborhood boys, mostly 9-12, spent lots of time with the railroad “bums” who would dismount in the mesquite before the train would stop in Las Vegas. The boys shared coffee, stew and lots of humorous stories with those “bums”. (We do plan to donate next month!)