Author’s note: One of the major “news values”—factors that generate media attention—is “impact”: How much of your audience is affected, and to what extent? A low-impact story, such as a flood of sewage into the basement of a single home, affects relatively few (although it’s certainly of overwhelming import to the home owner), and is, therefore, a low-impact story—not much media interest. Some stories, such as an earthquake, are high impact; they affect the entire community, and attract everyone with a camera, a notebook and a deadline.

When Jim asked me to write a series of columns about my Moab journalism career for the Zephyr, after some thought, I decided to pretty much stick to lighter, frequently funny subjects. After all, I wasn’t a reporter anymore, so didn’t have to cover day-to-day stories, and could write about whatever I damned well pleased; I was doing it for fun, and my readers could probably use the relief.

Occasionally, however, an event is so major, with perhaps even historic significance, that the memories, both good and bad, should be preserved while we are still around to tell them, and I’ve put this one off long enough.

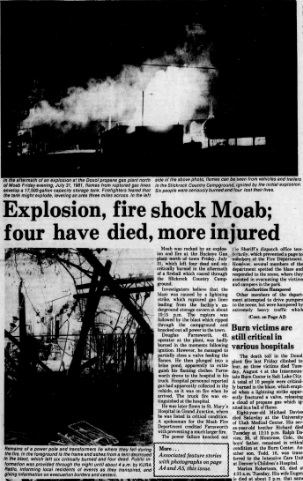

This high-impact story, of which I was a small part, was anything but funny: Ten people were seriously burned, and five of them later died—in the July 31, 1981, Doxol fire.

It was about 10:15 p.m. and cooling, after a 106-degree Friday. The baddies had just kidnapped Indy’s girlfriend, still hiding in a large basket, and tossed her and the wickerware into the back of a truck, when the theater’s power went off. Nowadays I can’t see that “Raiders of the Lost Ark” scene without instantly traveling back 40 years.

The hall got dark—seriously dark—in-the-bottom-of-a-cave dark, as there were no emergency lights. Still, Kris and I, and everyone else in the audience, waited quietly for resolution, which, as it turned out, wouldn’t have arrived until 7:30 the next morning.

However, patience had its limits, especially after a theater employee came in with a flashlight, announced the obvious, and left. Kris, following the fading beam of the flashlight, trotted after the employee to ask just what the hell they intended to do with an auditorium full of people trapped in blackness.

Both employees in the place, Kris explained later, were using the one and only flashlight to guard the money in the till, and weren’t about to leave it, regardless of the crowd stuck in the auditorium. Kris, naturally, suggested that one employee guard the money in the dark, while the other escorted people out of the theater with the flashlight. Meanwhile, I used the penlight from my camera bag to guide a few folks out a side emergency door, who were instantly transfixed by a sight in the north end of the valley.

I turned to look and was transfixed, too. Amid flashes from an intense lightning storm, weird, brilliant, wavering orange light was reflecting off the sandstone walls in the vicinity of the Colorado River Portal. It was obvious something unique, very big and very bad was happening, and I suspected I knew the cause of the power outage.

To my eye, located in the south end of the valley, it looked as if the Atlas Mill might be on fire. It wouldn’t be the first time. I had a running battle going with Atlas management each time the volunteer fire department had been dispatched there. Management didn’t like publicity, and I didn’t like being told I couldn’t enter private property when a fire therein was being fought using taxpayer dollars and county volunteers.

Technically, they were right, but I figured I held the higher moral ground, and eventually developed a solution to being denied access: I simply parked my recognizable car outside the property and hitched a ride in with one of the firefighters—one time even hopping onto a pumper. I also carried a hardhat in my car so I’d look like one of the workers.

Suddenly, the most important thing in life became getting to the source of that strange orange light as quickly as possible. This was obviously going to be a huge story, and I was, by god, the town’s reporter. With the departure of the penlight, the rest of the crowd was on its own in getting out of the auditorium. Kris, who had exited through the main front door of the theater, saw the glow, and, knowing my attitude toward breaking news, ran to the car ahead of me.

As we roared (well, as much as a 46-horsepower VW engine could roar) out of the parking lot, I turned up my pocket scanner, puzzled by the lack of radio traffic. As was my usual practice in public settings, I had silenced all the channels except the two “beeper” frequencies used to dispatch the fire department and ambulance. Both had been silent during the movie, and even with all frequencies on, there was almost no voice communication on the law enforcement channels.

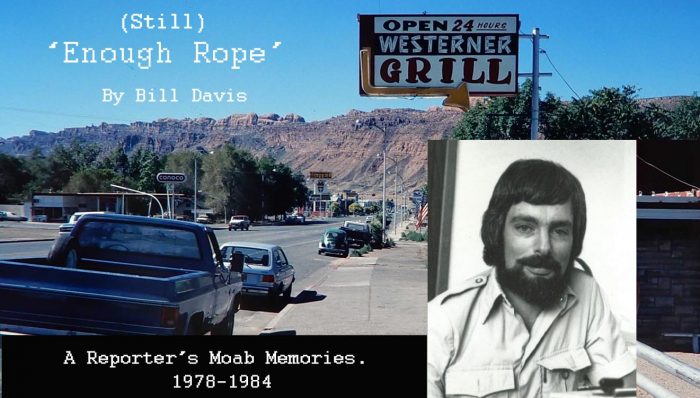

We made good time until we hit 4th East, where traffic seemed heavier than normal, even for a Friday night. It got worse on Center as we sped past The Times office and turned north onto Main.

That’s when the floodgates opened. By the time we reached The Westerner, traffic had backed up and ground to a halt all the way out to the intersection with 5th West, as the entire population of town was apparently doing exactly what I was: heading north like moths to a bright light. It also became obvious that the fire was way closer than the Atlas mill. On the west side of the highway, that left only the Sundowner Restaurant, a commercial campground, and the Buckeye propane plant (This was long before the wave of hotels hit the north side).

“I’ve Got a Function”

Jammed up in traffic, my frustration level shot up: “What are these idiots doing? Dammit, I’ve got a function here!” Shouting and pounding the steering wheel had little effect.

After an interminable period, I spotted a red light approaching in my rearview mirror (the rim of which, one might remember, was brittle and cracked from melting in the Green Well fire during my first week in town in 1978.)

The red light was on the fender of Grand County Chief Deputy Lynn Izatt’s patrol car (odd, how often Izatt turns up in my stories). He was picking his way down the center of the highway, which was now clogged in both directions. After a second of indecision, I pulled out behind him, which was probably illegal, but I didn’t care; I had to get to that fire.

It took approximately a month, but we eventually arrived at a roadblock set up by the cops, sheriff’s office, UHP troopers, and fire department at the intersection of 191 and 5th West, where they were turning traffic around. I wondered why the roadblock was so far away from the fire, which, it was now apparent, was at the Doxol plant. I learned the reason when the officers and I, during a hurried briefing by the fire department, were informed about something that sounded like a “blevy,” an abbreviation for Boiling Liquid Expanding Vapor Explosion.

BLEVEs occur when an external heat source is applied to a liquefied gas storage tank. Propane is stored as a liquid, as much more can be stored as a liquid than a gas (One gallon of liquefied gas will expand to 250 gallons in a gaseous state).

As propane boils at minus 240 degrees Fahrenheit, the only thing keeping it liquid in a tank is pressure. If the liquid is heated and begins to boil, pressure increases. To prevent overpressure, all tanks have relief valves, which allow gas to escape. When heated sufficiently, however, the pressure can exceed the design parameters of the tank, which ruptures, releasing liquid that instantly explodes into a gas. If the gas encounters an ignition source, it erupts into a fireball.

That is what happened in Kingman, Arizona, on June 25, 1973. As propane was being offloaded from a railroad tank car to a Doxol storage facility, a leak developed in a connection. Standard procedure to tighten the connection was to strike it with a brass-containing, non-sparking wrench. A worker apparently struck the connection with an aluminum-alloy wrench containing magnesium, rather than brass, which resulted in a spark that ignited the leaking gas.

Flames from the leak heated the tank, which the Kingman Fire Department, mostly volunteer like Moab’s, attempted to cool with a couple of small lines. Firefighters were attempting to place a large-volume deluge nozzle to spray the railroad car, but never got the chance. The overheated tank failed, resulting in a BLEVE and fireball.

Eleven firefighters, 10 of them volunteers, died as a result of the blast. The fireball also burned over 95 civilians who police were attempting to hold at a distance of 1,000 feet from the burning tank car. The incident has become a classic of fire service training programs throughout the country. This information, by the way, comes from an excellent article by Robert Burke in the July 1, 1998, issue of Firehouse magazine.

I mention all of the above not to make readers experts on BLEVEs, but to show what Moab officials were up against.

Coincidentally, earlier in the year I had done a feature story on Moab’s Buckeye propane plant, which was printed in the Feb. 5 issue of the T-I. In it, I described how five million gallons of propane were stored underground at a depth of 1,500 feet, in a cavern created by injecting water into a salt layer, then pumping out the brine. A second cavity was excavated after five million gallons of gas in the original disappeared—somewhere—resulting in some dark rumors around town. The missing gas never did show up, and a second wellhead was installed to the new reservoir.

The Explosion

Sometime shortly after 10 p.m., a flexible coupling in a surface pipe between the underground cavern and large above-ground storage tanks failed, releasing a large cloud of propane under pressure with an overwhelmingly loud hiss.

The gas, being heavier than air, hugged the ground as it moved south from plant through the only barrier between the Doxol site and the adjacent Slickrock Campground—a chain-link fence.

One long-term resident of the campground told me he was watching TV in his trailer when he heard the hiss of escaping gas. He quickly exited the trailer and ran south, TV remote still in hand.

“I looked down at the remote, thought, ‘I won’t be needing this again,’ and threw it over my shoulder as I ran,” he said.

Several other campground residents escaped on foot, but some did not, as the gas, inevitably, found an ignition source and exploded.

At the same time, Doxol employee Doug Farnsworth, 49, a Moab resident, attempted to close a valve feeding the broken line. He almost got it shut, but was severely burned when the gas exploded. His clothing in flames, he dove or was thrown (accounts varied) into the nearby brine pool, used to store water pumped out of the cavern.

Despite his burns, Farnsworth drove to the hospital in his own truck. A nurse at Allen Memorial told me when she went outside to assist him, propane collected in the cab and bed of the pickup was still burning.

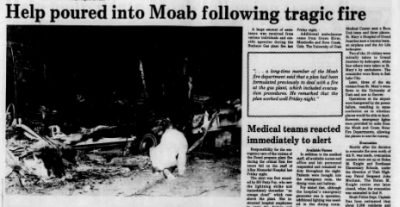

Back at Slickrock, bystanders were aiding an additional nine victims. Two were transported by a Grand County ambulance crew; the remainder were brought to the hospital by private vehicles.

Ten seriously burned patients severely stressed Allen Memorial’s staff and infrastructure, especially when the power was out. Fortunately, the hospital’s emergency generator had kicked in, but only provided electricity to the ER, a hallway, and the dining room, which were all used for treatment of the victims.

In an interview after the fire, RN Patty Foy told me that shortly after the arrival of the patients, Western River Expeditions, whose warehouse was nearby, provided several portable generators, allowing some victims to be moved to the dining room.

“We had more light than we needed within 10 to 15 minutes,” she said.

Such assistance, from numerous sources throughout the state and surrounding area came to characterize Moab’s disaster, as victims were transported to burn units in Salt Lake City and Colorado.

Meanwhile, the fire department and law enforcement officials were trying to deal with a potential BLEVE at the gas plant. The effort was made more difficult by the temporary failure of the sheriff’s office generator, which had knocked the dispatch office off the air at the moment of the explosion, hence the lack of dispatch tones and radio chatter I had noticed while still at the theater.

A lightning strike also knocked out the repeater station at Blue Hill, further complicating communication problems, limiting officers and fire units to vehicle and hand-held radios. Mostly, first responders had done what I had: seen the orange glow and headed toward it. A command center was later set up by Moab Police and the sheriff’s office at the visitor center located then on the north end of town.

Fire units were being held at the 5th West roadblock, to avoid a repeat of the Kingman disaster. Kris was there too, waiting with my car. Absorbing just how great the threat was, I asked her to take the car and retreat to her apartment on 4th North. My suggestion was at least partially selfish, as I wanted to worry about only one person if this thing blew.

That was the main topic of discussion among officers at the roadblock, with which I heartily agreed, along the lines of “I ain’t going out there if that fireball is going to be 1,000 feet across.”

“Would You Like Some Pictures?”

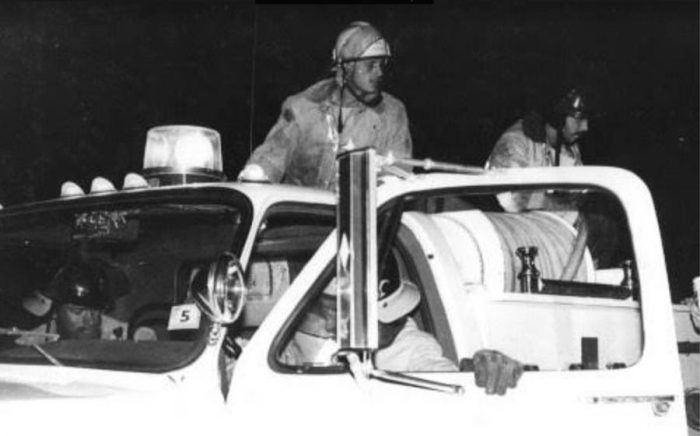

Just then, Fire Chief Troy Black pulled up in his department pickup, on his way to reconnoiter the fire before sending in any units. He picked up the microphone to his radio and activated its P.A. speaker.

“Bill Davis, would you like to go get some pictures of the fire?”

Without thinking, I trotted over to the truck and climbed in.

Sure.

This probably wasn’t the smartest thing I’ve ever done.

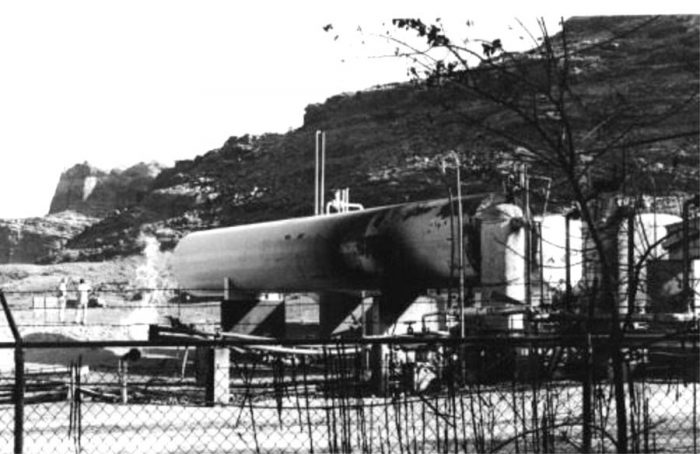

Troy and I proceeded up the highway to a point directly opposite several 11,800-gallon storage tanks near the entrance to the plant, perhaps 150 feet away. Flames from the ruptured line were wrapped around the south end of one of the tanks, looking for all the world like a demonstration of how a BLEVE occurs.

Troy stopped the truck to observe, while I jumped out the passenger side and steadied my camera and boss Sam Taylor’s zoom lens on the hood. I wasn’t sure if the camera’s light meter could handle the contrast of flame and darkness, and I knew a slow shutter speed would be required, so I braced and fired away, using the autowinder so I didn’t have to drop my eye from the viewfinder.

I don’t recall being frightened, just excited, and concerned about getting some useable shots under difficult circumstances. That sort of thinking has resulted in the deaths of combat photographers ever since photography was invented.

Suddenly, the night was split by a massive roar. Troy and I looked at each other with the same thought: This is it; the tank has fractured and is exploding. I backed away from the hood and around the open passenger door at the same instant Troy floored the gas pedal.

As the truck moved off I dove onto the floor of the cab thinking, with a total lack of logic: “I’ll tuck under the dashboard and let the fireball roll over the cab.”

You bet.

Thinking about it later under more rational conditions, I realized searchers might have found the frame of the truck, but little else. Diving to the floorboard would have accomplished exactly nothing.

Obviously, since I’m here to describe it, the tank didn’t BLEVE. The roar, which sounded and felt like standing behind a half-dozen 747s wound up for takeoff, was the 40-foot-long container’s emergency valve doing what it was supposed to, and relieving overpressure. Surprisingly, the cloud of gas spewing from the valve’s 20-foot mast was not ignited by the flames encircling the tank.

Had the tank been heated sufficiently to rupture, it would have taken out the other four or five, resulting in a blast even larger than the Kingman explosion. They might not have found the truck’s frame after all. And, considering one of the ends of the Kingman railroad car was found a quarter-mile from the site of the BLEVE, houses in the north end of town might have burned, possibly including my own on Westwood.

Additionally, officials were concerned a BLEVE might damage or destroy the storage cavern’s wellhead, located at the west end of the plant, resulting in the uncontrolled release of the underlying five million gallons of pressurized propane—a nightmare scenario.

In line with this possibility, law enforcement officers from the city police, sheriff’s office and highway patrol started evacuating the north end of town, extending from the roadblock south to 4th North, and later, to 2nd North. Officials later estimated about 3,000 people were eventually evacuated. This represented over half of the 5,330 residents recorded in the 1980 census. Emergency shelters were opened at Southeast Elementary and Helen M. Knight schools, but received relatively little use, since evacuees tended to stay with friends or family. The HMK site was closed when the original evacuation was expanded. North of town, National Park Service rangers, sheriff and fire units stopped traffic at the Arches entrance, and opened the visitor center for those stuck in traffic by the blockage.

With Farnsworth out of the picture, attempts were made to contact the manager of the gas plant for advice on how to halt the flow of gas from the five million gallons stored underground to the flames still wrapped around the storage tank; however he proved to be out of town. A call was placed to the company’s facility in Monticello, and another Doxol employee was dispatched to drive north.

Two of the 10 victims, who were all in critical condition, were flown by helicopter to St. Mary’s Hospital in Grand Junction. St. Mary’s also sent a trauma team and one airplane. With the power outage, a landing zone at Moab’s hospital, which had no formal helipad, had to be lit by vehicle headlights. Four victims were also taken by ambulance to Grand Junction.

The same problem predominated at Canyonlands Airport, where the power was also out. The University of Utah Medical Center sent a team from its burn unit and three fixed-wing aircraft to evacuate victims. Their landings and takeoffs were lighted by units from the Moab and Green River fire departments.

Running the Gauntlet

Additional ambulances came from Green River, Monticello, and Dove Creek, Colo. Each, as they left town, had to run the same gauntlet past the Doxol plant that Troy and I had. An additional ambulance and a patrol unit were provided by the Park Service, which also had to be driven past the fire (the ambulance by one James Stiles) on their way south from Arches.

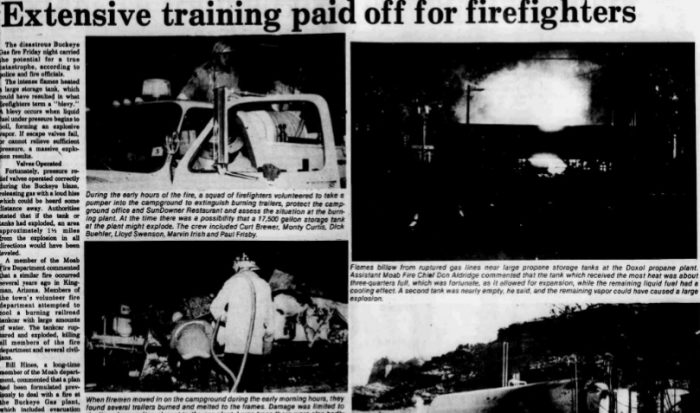

After Troy returned from our scouting trip, he sent a single pumper with volunteers (which, I guess, made them volunteer volunteers) into the campground to extinguish the fires there and report on the condition of the storage tanks. The crew included Curt Brewer, Monty Curtis, Dick Buehler, Lloyd Swenson, Marvin Irish, and Paul Frisby, to give credit where it is certainly due.

Shortly after, I returned to the scene, although, with the crush of events and an aging memory, I cannot recall how I got there. I probably grabbed a ride from a fire unit or Lynn, who was also making runs to check on the fire.

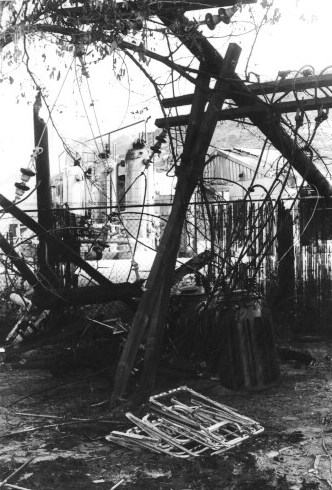

But there I must have been, as some of the photos taken in the campground still show flames around the tank in the background. Several trailers burned to their frames, while the walls of others were melted into bizarre shapes. A van was also gutted.

The most heartbreaking sight was the remains of some tents, with the nylon almost totally burned away, the frames twisted and partially melted. Children had been in those tents.

Firefighters had planned to string hoseline from a hydrant near the Black Oil Company to the fire scene, but found it producing only 20 pounds per square inch of pressure, far below what was needed. The lack was the result of the power failure, which prevented the refilling of the town’s million-gallon water tanks, usually done during the nighttime hours.

Advisories called for pumping a minimum of 500 gallons of water per minute to cool propane storage tanks threatened with a BLEVE. Additionally, extinguishing the flames without being able to shut off the gas flow would allow the continued release of unburned clouds of propane.

While county fire units were extinguishing the fires in the campground, the Monticello Doxol employee arrived, and was able to close valves cutting off the flow of propane from the underground cavern, thus preventing a BLEVE. Residual gas in the plant’s many lines continued to feed the flames under the tank, although at a much-reduced rate. Although the sky was still dark, daybreak was approaching, hinting at the end of a long, long night

Now that the worst of the crisis had passed, I faced a ridiculous problem: My eyes were killing me. I had failed to carry a contact lens kit in the camera bag, and I was way over the permissible number of daily wear hours. The pain made it difficult to concentrate and my vision was badly blurred.

I hitched a ride into town to check on Kris and recover my car. When I attempted to drive north to my Westwood home on 1st West, I was stopped at one of the many evacuation roadblocks. Officers from out of town manning the roadblock hadn’t yet got the word that the danger had passed, and refused to let me through.

I tried to explain that I had spent the entire night at the fire scene, and my eyeballs were about to fall out. He was unmoved, commenting, “You’re the second person to come through here with that excuse.”

“I’ve just come from the fire scene. I’ve been there all night and really, it’s okay now,” I pleaded. No dice.

Finally, out of the fading darkness came a voice from one of the local officers who knew me.

“He’s okay. Let him through.”

In a few minutes, I was home in the empty neighborhood as the sky over the LaSals began to lighten, removing those damned lenses and staggering into the shower. A Park Service unit on patrol passed by, and I wondered if I was about to be ordered out of the house, but they didn’t stop.

Bed sounded like a fine idea, but I knew this would be impossible. The magnitude of the disaster meant I would have to follow story leads in all directions as hard and as fast as I could over the next four days to be ready for Wednesday publication.

I owed the townspeople the most complete and accurate information I could gather, as there would be thousands of questions. It was the biggest professional challenge of my life, and I was determined to make a good job of it. To do less would have meant failing my obligation to the community, so, after a shower, I headed out the door and went back to work.

To avoid being overwhelmed, I broke down the event into individual topics for a series of stories, asking what readers would most want or need to know.

Devastated Family

Most obvious, and painful to deal with, was the identity and condition of the victims. I learned the propane blast devastated a Montrose, Colo. family.

When the fireball ignited, the 36-year-old father attempted to rescue his three sons, who were inside tents in their sleeping bags. Although all were alive when they were transported out of Moab, the eight-year-old died Saturday, Aug. 1. His brother, 7, died four days later. The father, burned over 85 percent of his body, lived until Sept. 29. All had been treated at the University of Utah’s Intermountain Burn Center. A 16-year-old son was also seriously burned, but survived, after being treated at a hospital in Denver.

The two other fatalities were a married couple from Markham, Texas, the man aged 63, the woman, 60. They also had been flown to the Burn Center. Both died on Aug. 11.

I also detailed the law enforcement assistance that poured into Moab. At one point, an estimated 40 officers were on duty patrolling the evacuated area and manning roadblocks, including deputies and sheriff’s posse members from both Grand and San Juan counties.

One of the most amazing factors of the disaster was the willingness of townspeople to pitch in and help wherever they could. Water tankers were volunteered, food was provided by both businesses and individuals, and local radio station KURA managed to come back on the air during the blackout, providing details on the fire and the evacuation throughout the night.

Power was restored Saturday morning by crews who moved in when the fire situation had stabilized.

Later Saturday afternoon, TV news crews from all three network affiliates in Salt Lake arrived in town to cover the disaster. I watched as all three reporters did their stand-ups in front of the only fire remaining in the plant—a three-foot flame issuing from a small pipe that was flaring off propane remaining in the Doxol system. They looked ridiculous in person, but I had to admit the setup looked great on the evening news. KSL used one of my still shots from the night before.

The story went national, picked up by The Washington Post and United Press International, one of the few events I covered during my time in Moab that did so.

As far as I know, mine were the only photos of the fire at its height. They did not turn out particularly well.

I was determined, however, that my coverage would be more detailed, and complete, than any other; this was my town. Sam included a couple of extra pages for the disaster coverage, so we ran 32 pages, which I had to fill.

Bizarrely, in the midst of all the work, Kris and I took a Sunday trip over to Paradox Valley so I would have a B-1 travel feature, which had become a weekly tradition. Newspapers always have a voracious appetite for copy, and I was back to covering the city council Tuesday evening.

The coverage holds up pretty well, I think, except for a couple of errors: Pretty much everyone, including me, was sure the flexible coupling failure that initiated the explosion was caused by a lightning strike; the thunderstorm that occurred at the time of the failure was one of the most intense I’ve ever seen. Later investigations by government agencies and lawyers handling the over-$200 million in lawsuits filed in connection with the fire called this into question. A solid wall was later built between the campground and gas plant.

Also, I was misinformed about the number of casualties in the Kingman incident, and incorrectly reported that all members of the volunteer fire department had died; the correct number was 11 of 36.

If you are curious, you can read our coverage of the Doxol fire HERE, on the “Utah Digital Newspapers” Archive.

As you read, remember that every single fact in each of the stories was the result of a question, asked either in person or on the phone; there are many, collected and written in a short period of time.

A journalist’s soul is in those pages.

Afterword: Everyone who lived in Moab on July 31, 1981, has a story to tell. Ask them.

Los Angeles-born BILL DAVIS first came to Utah as a student, where he earned his Bachelor’s degree in Journalism from Utah State University. He spent his wayward youth working as a graphic cameraman and photographer, then as a musician. In 1978, Bill was hired as a reporter/columnist for Moab’s Times-Independent Newspaper before returning to USU with his wife Kris and gaining his Masters Degree. He taught Journalism at San Joaquin Delta College in Stockton, CA for 24 years, until his retirement in 2010. Now he and Kris live in Salt Lake City, UT.

To comment, scroll to the bottom of the page.

Zephyr Policy: REAL NAMES ONLY on Comments!

Don’t forget the Zephyr ads! All links are hot!

Great review of this incident and your personal coverage; sad to say that all the folks living on top of thin soil veneer covering massive, highly soluble salt in Moab valley might experience their own personal accident in future as underlying salt dissolution allows valley to continue to collapse and sewer lines to gas lines break; see additional comments I left after Jim’s post about this fire.

Great article Bill Davis! I remember when this happened. I was living in Carrollton, Texas and caught the tail end of a news story about a fire in a small town in Utah. I had missed finding out which small town and because there are so many small towns, I thought, the chance that it was Moab was minute. Besides, what could I do being 1,000 miles away except worry? I decided not to call my family, whom I reasoned were probably already asleep. I went to bed not knowing that my family at 4th East and 1st North were preparing to evacuate their home if that became necessary. Had I known that my cousin Vilate Farnsworth’s husband Doug was so severely burned, I most certainly would have prayed specifically for them and agonized for Doug and the other victims. This was a life changing event for Vilate and Doug and their family. Later, when I learned the extent of the injuries and the plight of the victims, I was horrified. Such a sad event in the history of my beloved hometown. But it is important that we remember and pay tribute to the heroes of the disaster. For being so remote, Moab and the surrounding area were sure able to marshal a lot of manpower and resources! For those times, it amazes me!

I still have copies of the story I filed for the Salt Lake Tribune.

Bill’s report is very well done. Great journalism. The Doxol explosion was horrendous and it shook Moabites to the bone. I remember the wave of horror that washed over the town with the loss of those children. The accident devastated us, but…it could have been so much worse had local heroes not stepped in. Doug Farnsworth is a legend.

My father was the 16 year old son that survived the explosion. the Montrose Colorado family. He lost his father and two brothers in that fire. My father is still alive today and that day will forever be a part of him

Alicia, I just came upon this article because Ralph was married to my aunt Twila Kaye Davies at the time of the incident.