(From the 1995 Zephyr archives)

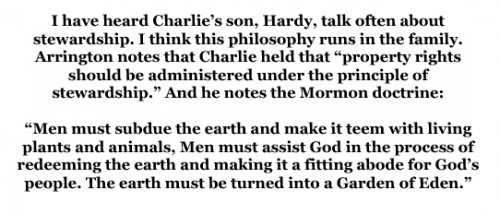

Years ago, when Hardy Redd, my neighbor friend across the mountain, told me that the Mormon historian Leonard J. Arrington was to write a biography of Hardy’s father, the legendary Charlie Redd, I was quite thrilled. The book was published under the appropriate name, Charlie Redd, and as I read it, my thoughts continually turned toward my own experiences and that of my ancestors who also settled this region. So I’ll interject an account of these with that of the Redd family—a kind of a personal review of history.

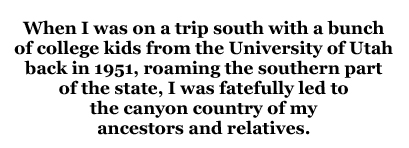

When I was on a trip south with a bunch of college kids from the University of Utah back in 1951, roaming the southern part of the state, I was fatefully led to the canyon country of my ancestors and relatives.

That motley travel group was made up of a mixture of talent. Neldon Christensen of Monticello himself, provided local interest and history. He told me of the influential Redd family as we toured the graveled and dirt roads (few paved roads then.) Redd, he said, was one of the largest stockmen in Utah. And Blaine Busenbark, the nephew of old riverman Bert Loper, filled me in on the Colorado River. And photographer Jim Dean who had been on a Bert Loper/Moki Mac Ellingson river trip through Glen Canyon extolled the virtues of Glen Canyon and the Hole-in-the-Rock. And Bob Waite, to become a college history professor and the maker and defender of national parks (some that Congressman Jim Hanson would now dismantle) was the master trip planner. And Richard Elzinga, who taught me to better appreciate bugs and butterflies, became a top scientist in his insect world.

Through travel and reading, I grew more aware of the history and environment of the canyon country. I found little difference in the environments that the Redds grew up in and that of my own. At times our experiences seemed to overlap.

So as I read the book, my Walter Mitty mind could not remain quiet. History surely is dynamic and alive. In that there is such a thing as “guilt by association,” I felt a pleasant feeling in associating my past kin to that of the Redds. Mutually, our ancestors shared the guilt along with the rewards. Today, we all are the recipients of their struggles.

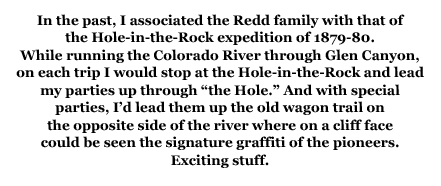

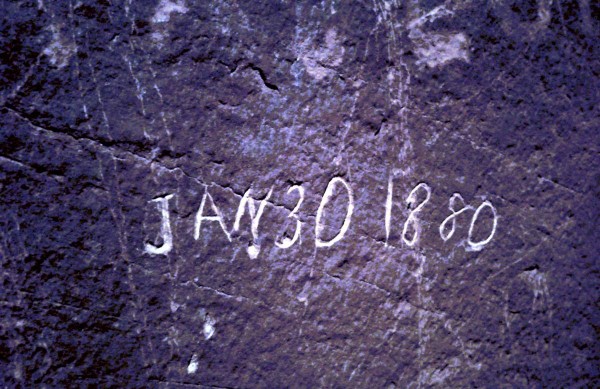

In the past, I associated the Redd family with that of the Hole-in-the-Rock expedition of 1879-80. While running the Colorado River through Glen Canyon, on each trip I would stop at the Hole-in-the-Rock and lead my parties up through “the Hole.” And with special parties, I’d lead them up the old wagon trail on the opposite side of the river where on a cliff face could be seen the signature graffiti of the pioneers. Exciting stuff.

I carried the book, Hole-in-the-Rock, with me, in which I became totally absorbed. The author, David E. Miller, was a professor of history at the University of Utah and I was well acquainted with his past works. First published in 1959, the book became my favorite “guide-book” and on river trips and over driftwood campfires my guests read often from my water-logged edition.

But little did I know at that time that the rustic characters of the Hole-in-the-Rock journey would play an even greater part in my mind. As an avid aficionado of history and genealogy, my interest centers on the early days of Utah’s pioneer settlement. Since those Glen Canyon days, I’ve learned much more concerning that difficult faith-inspiring trek.

The Redds were a part of that drama. So let’s follow John Hardison Redd, Charlie’s great grandfather, an old sea captain and mariner who had settled in Virginia and then North Carolina. Lemuel, his son, was born in 1836 at Sneads Ferry, North Carolina.

In 1843, a bunch of Mormon missionaries, including the notorious John D. Lee, did missionary work for the new Mormon religion. The Redds were converted and moved west in 1851 settling in Spanish Fork. In January 1856, young Lemuel, now 19 years of age, married Keziah Jane Butler. In June they were called on a “mission” to Las Vegas, Nevada. Shortly, they returned to Spanish Fork where they had their first son, which they also named Lemuel.

But not all went smoothly. For instance, in 1857 General Albert Sidney Johnson brought the might of the United States Army to put down the “Mormon rebellion.” Then, in the Fall of 1857, some 120 Missouri emigrants, enroute to California, were killed at nearby Mountain Meadows by John D. Lee and other Mormon settlers and their Paiute allies.

This upset things for a while, but soon Mormon families again continued their colonization efforts.

Lemuel and Keziah Redd were then “called” to help settle New Harmony in the Spring of 1862. In November 1866, Lemuel took another wife, Louisa. Both wives bore large families.

In 1870, Lemuel bought the John D. Lee farm at the head of Ash Creek. Lee had settled at nearby Fort Harmony in 1852, but had to abandon that place when two of his kids were killed when their house fell in during a flood. Then they made the move to New Harmony.

George Spencer, my great-great-granddad, probably taught the Redd kids at New Harmony when he went there to teach in 1867. He reportedly also had once taught at John D Lee’s private family school.

Spencer took on three wives and had 22 children. He died in 1872, at the young age of 42, as he was searching for more places for the Saints to colonize. His death spared him the travails of the approaching San Juan Mission (Hole-in-the-Rock trip) and the need to dodge federal deputies.

New Harmony and other southern Utah towns entered the United Order in 1874 and the Redds, the Spencers, and other families became involved in that enterprise.

In 1877, Lemuel Redd attended the dedication of the St. George temple. The dedication drew leaders from all parts of Utah and Idaho. My other great granddad, Thomas Sleight, who had previously been “called” to the Bear Lake country in Idaho, made the long wagon trip south to attend the services and to gain the special council of Brigham Young. Returning to Idaho, groups were organized to head for Arizona to settle, even though he and his family decided to stay put.

Thomas’s son, George, (my grandfather) would soon marry into the Spencer line (our most polygamous line.) There was some thought they might yet head south, but as they were already in a great tangle of relationships, they too stayed put while the polygamous sector of the family in Idaho later high-tailed it to Canada. Some in our Stevens family line went both south and north.

Other far-reaching effects radiated from those St. George temple services. Brigham Young, intent on furthering the settlements of Arizona and southeastern Utah, set the stage for new missions. But there was an unexpected delay as he died later that same year.

Continuing its plans for settlement of southeastern Utah, the church leaders finally formed the San Juan Mission in the winter of 1878-79. The settlers were gathered from a host southwestern Utah towns such as New Harmony, Holden, Panguitch and Cedar City.

Some 80 families were “called” by the new Mormon leadership to establish a settlement at Montezuma Creek on the San Juan River. The party would take a “shortcut” through canyon country that had never been totally explored. They thought the trip would take them only six weeks.

Other families were “called” throughout southwestern Utah. My own great grandfather, John Horne Miles, escaped being called as he was in the state penitentiary and up to his ears in polygamous problems. It was a real mess. It seems that he fell in love with Emily Spencer, the daughter of the late George Spencer. He married her and his former English girlfriend on the same day at the Endowment House in Salt Lake City. Emily was “sealed” to him first and the former girlfriend was sealed second. But this upset the former girlfriend as she wanted to be sealed first.

Then, after slapping Emily and creating a scene, the former girlfriend ran to federal agent “polyg-hunters.” The feds quickly threw John into jail for the crime. Finding him guilty, the court sentenced him to five years in the pen and a fine of $100. Though he appealed the sentence, John was cheated out of the chance to help establish the great “shortcut” through the canyons and to colonize southeast Utah. (And, as a footnote, John’s new English wife ran off with one of the U.S. Deputies assigned to the case.)

John had to be content on seeing other of his kin make the journey.

This included connections with the Sevy, Pace, Stevens, Perkins and other families of this historic party.

And after settlement, even more of the Spencer family were to drift to the San Juan country. In this regard, Emily Washburn, from the Spencer line, married Charlie Redd’s first cousin.

Over 200 people, 83 wagons, each with two or more teams of horses, about 200 additional horses, and more than a thousand head of cattle were involved in the winter of 1879-80.

I suppose the Hole-in-the-Rock itself is the most singly significant part of the entire trail. Here the construction of the passageway to the river was extremely difficult. Picks and blasting powder were used to widen the crevice. A road, named “Uncle Ben’s dugway,” was built on the side of a sheer cliff wall. Stakes were driven into the rock and vegetation, rocks, and sand were piled on top of that. Six weeks were spent here.

They journeyed over 290 miles, much of it through steep-gorged canyon country. The winter journey lasted six months, rather than six weeks, averaging out maybe 1.7 miles per day. Arriving finally at the present site of Bluff, the exhausted and spent party decided to stop and make their settlement. The site was good enough.

My interest in Glen Canyon, the Escalante Canyon and the Hole-in-the-Rock trail inspired me to move to the town of Escalante in the heart of the canyon country. This I did by uprooting my wife and children from Bountiful after giving them good reason they should be uprooted. In Escalante I met relatives that I had never known. My grandmother herself had once lived in Escalante when her father, John Horne Hiles, moved there to teach after his appeal to the U.S. Supreme Court had been heard and his case dismissed. (He took no further wives.)

Now that we have rambled on through history, let us turn our attention to the Redds’ treatment and philosophy concerning the environment.

Arrington notes in his book that when the Hole-in-the-Rock settlers arrived in Bluff in the Spring of 1880, the range had already been heavily grazed. In the late 70s and early 80s, thousands of cattle from Texas and other western states arrived in the canyon country to feed on the free grass. There came a race to “use up the grass before someone else got to it.” Sheep were introduced in the 1890s, and along with the cattle, the rangelands were being destroyed. The Redds acknowledge that.

Charlie Redd, noting the deteriorating ranges, struggled to reclaim the range lands. Building hundreds of miles of fences, he concentrated his cattle in areas in which he wanted them concentrated. He built stock water holes and troughs, range trails, and seeded thousands of acres of range land. He ripped out many acres of sagebrush, juniper and pinyon pine and planted crested wheatgrass in their place. Arrington reports that good grass stands were obtained and the watershed was greatly improved.

I don’t agree with all of the measures taken by Charlie Redd, under today’s conditions, (chaining for one.) However, in this book we are looking through the eyes of a very successful rancher/stockman who came to really know his business. And he learned it well. This book portrays five generations of land management through the eyes of the Redd family.

This book, though very enlightening, has not changed the way I myself view land management. In my opinion, certain grazing lands can be successfully managed by responsible ranchers without greatly damaging the resources. I have no problem with zoning certain lands for proper grazing practices, just as I have no problem in setting aside wilderness areas for other purposes. The point is that we each must manage lands the very best we can. We cannot afford to destroy the very things on which we are dependent or those things we hold of great value.

I have heard Charlie’s son, Hardy, talk often about stewardship. I think this philosophy runs in the family. Arrington notes that Charlie held that “property rights should be administered under the principle of stewardship.” And he notes the Mormon doctrine:

“Men must subdue the earth and make it teem with living plants and animals, Men must assist God in the process of redeeming the earth and making it a fitting abode for God’s people. The earth must be turned into a Garden of Eden.”

He quotes Brigham Young: “Men shall be stewards over that which they possess.” and he repeats another Mormon saying: “The earth is the Lord’s.”

Charlie Redd and his wife, Annaley, accomplished a great deal. One of their greatest accomplishments must surely be noted. In 1972 they established the Lemuel H. Redd Chair in Western History and the Charles Redd Center for Western Studies at Brigham Young University. The Center has been extremely successful and much good has come from it.

Charlie Redd died in 1975 in his eighty-sixth year. I wish that I had met him when I had the opportunity. He left a great legacy.

FOR MORE ON CHARLIE REDD:

http://www.byhigh.org/Alumni_

KEN SLEIGHT still lives at Pack Creek Ranch near Moab, Utah

To comment, scroll to the bottom of the page.

Zephyr Policy: REAL NAMES ONLY on Comments!

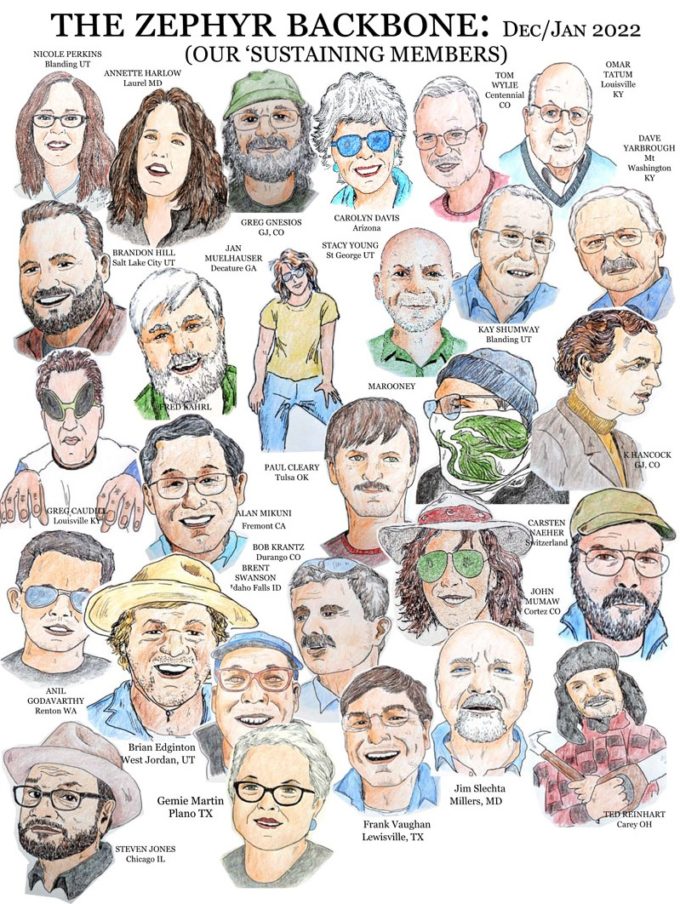

Don’t forget the Zephyr ads! All links are hot!