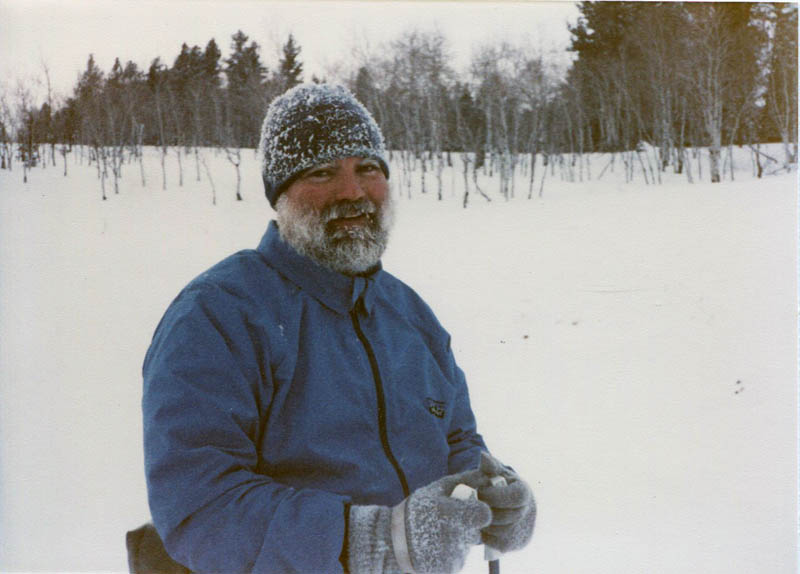

I felt it again, like clockwork, with the first snow. The snow was only a dusting, not even an inch, but I still thought of Dad. His pleasure in loading the plow onto the front of our car. The delight of an evening spent pacing the vehicle up and down the treacherous road to our house, clearing the path even as the snow still fell. “We aren’t going to get trapped this year,” he’d say, pulling on his hat and gloves. And he was right to worry. One year we’d been too late, and the snow fell too thick and wet for the plow to budge.

But that outward practicality only barely masked his impatience to get out into the weather. I felt it too, on those few times I accompanied him—the perfect, warm isolation from behind the car windows, the wet-dog aroma as snow melted off our boots, our woolen coats and gloved hands. Most of all, the ritualistic rise and fall of the plow. Like a monk pacing out rosary beads, his hands orchestrated each pass over the snow with the deliberate detachment of muscle memory.

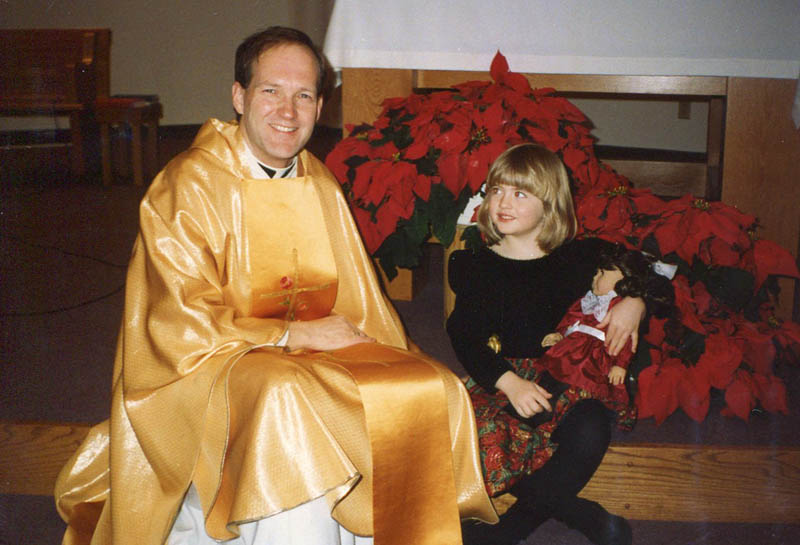

He was always teaching me about ritual, and about solitude. Each year, winter brought both to our isolated home in the forest. Mom and Dad brought in wood from the pile outside, to keep ready by the stove. We located the lamp oil and candles, and gathered them where they would be easily found in case of a power outage. The Advent wreath took its place on our dinner table and our weekly Mass took on an expectant solemnity, which impressed me even as a small child. The Advent readings hovered on the subject of preparation and readiness for the coming of God. We were in darkness, the Priest intoned from the altar, but soon there would be light.

I could say we weren’t a very religious family, but that wouldn’t be quite right. My parents, and especially my mother, were troubled by the Church where it intersected with politics—the incessant harping on abortion and homosexuality, the unsettled question of the role of women. But they were also faithful.

“Why are we Catholic?” I asked my father, as soon as I was old enough to have grasped that such a thing was a choice.

“Because,” he replied, “it was the only religion as sinful as me.”

This wasn’t the whole truth. He had responded to the Church’s intellectual history, and its reverence for contemplation and meditation. But the question of “sin” was certainly a part of the grueling intellectual process he had undertaken to leave behind his Southern Baptist roots. My father believed in sin. He was never quick to forget his own mistakes, and he disliked the rigid dichotomy of Sinful vs. Saved, which had been such a part of his childhood religion. To be “Saved” meant to be righteous (often self-righteous) and to be born again as a new person. Dad wouldn’t accept that a person can ever be wholly righteous, or that a person’s life of sins—which need remembering in order to inform your future actions—could be forgotten. To believe in a life free of sinfulness was self-delusion. And he refused to allow himself to be deluded.

He was a therapist by trade. I find it difficult to separate his religious contemplation from his therapeutic practice—both rested on self-examination. Those two parts of his mind informed each other. He spent a lot of time talking to me about seeing myself honestly. He showed me by example how to reflect on my actions and how to question my own motivations. And he spoke to me about being alone. He came to Catholicism by way of the monks. Exiles and outcasts, all of them. And he believed in the power of the lonely pilgrimage.

When I was in the Third Grade, and feeling rejected after an argument had cost me the company of my best friends, my father counseled me to accept the loneliness. To make peace with it. “It’s important to know how to be alone,” he said. “You need to enjoy your own company. That way you won’t make all your decisions in life based on needing someone around.” It was pretty serious advice for an 8 year-old, but I was listening. I would always remember his words, even if I didn’t yet understand them.

Later, he would talk to me about his own period of exile. Before he ever met my mother, or even dreamed of having a child, he had once been a psychologist at a prison in Arizona. He liked the work, he said. He did well with many of the inmates, who tended to appreciate being spoken to as human beings. My father’s manner was always funny and unaffected, easy to talk to. He spoke with a frankness that would have resonated with men who had seen the absolute worst of life. His trouble with the job wasn’t the patients, but with the staff and the whole prison system. Every small progress he made would be undermined or contradicted, and it was nearly impossible to spark hope in men who were living in that world. With time, it became impossible to spark hope in himself. He lost all his faith in the work.

Throw a messy and costly divorce into the mix, and the inevitable result was burnout. Dad quit the prison job. He left Arizona altogether. Not knowing how to move forward, and with nothing to return to, he took on a new career. He became a long-haul truck driver.

The truck driving taught him how to be alone. He learned what time means when it is stretched along the highways. One day, while killing time in a shopping mall somewhere, he discovered a book called “The Way of the Pilgrim.” A translation of a nineteenth century text, the book is the account of an unnamed peasant who sets out into the world with nothing, save for a prayer he repeats without ceasing. “Lord Jesus Christ, have mercy on me.”

The book became my father’s touchstone, and so did its prayer. Modeling himself after the peasant, my father used that prayer as a mantra on the road. It carried him through days and weeks of driving. Except, as I remember it, he altered the prayer slightly. He would say, “Jesus Christ, have mercy on me, a sinner.” He repeated that prayer until the words were feeling, more than speech. They were muscle memory. A bone-level ritual. He taught the words to me when I was young, and I memorized them along with my Rosaries and mealtime prayers. I still return to that prayer. And I wish I had asked him more about his term as a trucker. I love to remember that, once upon a time, his CB Handle was “Pilgrim.”

I still believe in the power of rituals, but not like when I was a kid. To a child, family rituals are gravely necessary. They’re elemental—with the enchantment and yearly renewal of sacrificial rites. Christmas, in my memory, reached its ritualistic apex in the Midnight Mass. The day before Christmas was pleasantly busy with final present-wrapping and food-preparing. Then, come late afternoon, we retired to bed. Mom or Dad would pull the curtains tight against the daylight, and settle me under the covers with a book, which would keep me company until I grew sleepy.

When I awoke again, it was nighttime. And we began a third mystical day, between the Eve and the Holiday. These special hours had their own wardrobe—my Christmas dress emerged from its garment bag in the back of the closet. Mom wore her long gray woolen dress coat; and Dad, his black coat and hat. We left our warm house and made the cold pilgrimage to the car, and into town, under cover of night. Turning back in my seat, I would usually steal a glance through the back window at our house, lit from within by the glistening tree and from without by garlands of multicolored lights.

Arriving at the church, we would meet the same friends and parishioners we saw every week, but they too were transformed by fancy dress and the strangeness of the midnight hour. We carried out the service by candlelight. Imagining it now, I can only remember the smell of candle wax, and the heady incense which lulled a small child to drowsiness. And I remember that I would grow emotional during “O Come O Come, Emmanuel,” transported by the solemnity of its Medieval melody. Even though the chorus called Israel to “Rejoice!” it was not a song about happiness. It was a song about living in darkness, and the longing for something better. It was enough to inspire in me, for that night, a fervent belief that I was in the midst of something supernaturally important.

Perhaps it was due to Dad’s influence—his interest in the more contemplative, and less joyful, aspects of religion—that the one false note of Christmas Eve was inevitably the last. When the lights came up and the church sang “Joy to the World!” I could never get into the spirit. I preferred the candlelight and the vigil for deliverance. I would still be thinking about what it meant to “mourn in lonely exile here/until the Son of God appear.”

My father used to say it disappointed him that I was so much like him. He also preferred the mournful songs about exile over those proclaiming release and joyfulness. But I could tell he enjoyed the company. “It’s too bad you’re this way,” he said more than once. “You’ll always run just a little under.” He’d pause. “Just like me.” And he would set out a seat next to him on Christmas Day, or any other busy holiday or family gathering. He and I would sit together, both feeling “a little under” everyone else’s enthusiasm. We would watch the action from the sideline.

In college, I found a quotation from among Emily Dickinson’s correspondence that captured my father’s brand of religion perfectly. I wrote the quotation in a notebook, which I carried around for years:

When Jesus tells us about his Father, we distrust him. When he shows us his Home, we turn away, but when he confides to us that he is “acquainted with Grief,” we listen, for that is also an Acquaintance of our own.

Dad always believed that religion, like art or journalism or anything vitally important, should afflict the comfortable and comfort the afflicted. He told me a story once—which, with time, I may have exaggerated or fictionalized in remembering—about one of the inmates he treated at the Arizona prison.

One day, in the prison yard, he told me, an otherwise ordinary inmate walked away from his fellow prisoners. This alone was cause for concern. The prison yard was highly segregated and any deviation from your group could prove fatal. Still, this prisoner had seen something and he crossed the yard alone toward it. He slowly approached the fence.

The guards had immediately come to attention; the whole yard was tensed, waiting to see what this prisoner would do; but they loosened their grip on their batons and let their hands fall from their holsters when they saw the man stop.

He stood just at the barrier between the prison and the field beyond. Opposite the man, from across the field, a doe had arrived. She waited, as everyone in the yard waited. Even the dust was quiet.

The prisoner reached a couple fingers through the wire and the doe allowed him to touch her, gently, on the head. Just once. Then she turned and she walked away.

Everyone was transfixed, Dad told me. Standing near the guards, he watched as the prisoner lingered just a moment longer at the fence before turning and re-crossing the yard to rejoin his group. Reality slid back into focus. The guards relaxed against their post and began talking among themselves, but no one said much about the scene they’d just witnessed, except maybe, “Well, huh.” or “Don’t see that everyday.” Life moved on. But Dad never forgot. He made a lesson of it for me, one afternoon, driving home from school. “Why shouldn’t a prisoner experience a miracle?” he asked. “Jesus preferred the poor and the imprisoned to the rich and comfortable.” Religion doesn’t do much good for the satisfied. Jesus came to help us manage our grief.

It is grief, after all, that makes me feel so religious, watching the snow fall. Grief has become my ritual at Christmas time. It has been eleven years, come December 20th, since Dad died. So suddenly and out of the blue that the words “suddenly” and “out of the blue” are insufficient. He was here and then, in a moment, his heart stopped and he was gone.

That particular Christmas of 2010 exists in my memory like a painful dream. I don’t like to return to it. It was going to be my first Christmas with Jim. Our first Christmas in Kansas. I had already bought a ham, which we abandoned, upon receiving that horrible middle-of-the-night phone call, to fly into the San Francisco airport. My parents had moved from South Dakota to California a few years earlier.

Christmas Day: Jim, my Mom, the dog, and me. We drove through heavy rain to visit a few of Dad’s favorite places. We didn’t know what else to do. In a daze, I half-expected Dad to walk out from behind every tree in Muir Woods. I expected him behind every rock on the freezing beach at Stinson. I watched Cooper, his dog, running in wide circles across the sand. It had only been a few days. I still didn’t believe he was gone. I had his phone number saved in my phone and I had already confused myself a couple times with the realization that, calling that number, I wouldn’t reach him.

In a quiet place, which was a special spot for my father, under a particular tree, we buried a little memento of him. It was a heartbreaking thought, burying it—and, again, burying him, a week later—that I was also mourning the end of that era of my life. The era of intact family rituals. The era of hearing my father’s advice. Each memory of Christmas would be a memory of this grief.

I refuse to lose my memories of him. And so, to keep the memories intact, I let myself grieve—this year, like every year. And I return to those religious thoughts, to the Catholicism of my childhood, with the coming of each snow. It’s all tied together. My father, his beliefs, his rituals.

I know that, whatever else I believe, I do believe that faith is meant to bring a relief for pain. Not that religion has ever brought me any answers, or settled any of the eternal debates I puzzle over. In truth, I don’t expect answers anymore. In lieu of answers, I am grateful for mercy. If Faith lessens the sting of my loss, then I welcome it. It brings me some comfort when I’m troubled, and so I accept it. With the hush of snow. With the sweetness of memory. I allow myself to believe, not in the God of the Church, but in the God of my father’s stories. The God of pilgrims and lonely exiles. A God who shares my acquaintance with grief.

Tonya Audyn Morton is the former publisher & managing editor of The Zephyr. She is now the founding publisher/editor and frequent contributor to “Juke,” an arts and literature journal on Substack. Zephyr readers can access Tonya’s page here. And on Facebook.

To comment, scroll to the bottom of the page.

Zephyr Policy: REAL NAMES ONLY on Comments!

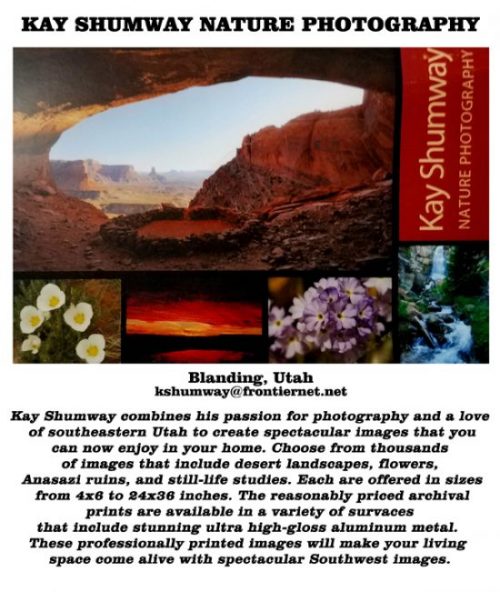

Don’t forget the Zephyr ads! All links are hot!

Tonya. First I’m so sorry for your loss and at a tough time of year. Your story about your Dad is beautifully written. Thank you for sharing with everyone.

What a lovely piece.

Tonya Stiles, please keep writing. You have a gift.

Tonya Stiles, please keep writing. You have a gift. This story about your father is so so good!

Great piece.

Thank you, Tonya, a beautiful piece of writing and a truly beautiful story.

What a lovely remembrance.

If Tonya wrote a book, I would buy it for me and all my friends.

Beautiful. Just beautiful, Tonya.

Wonderfully written, Tonya, and a gift to all of us. I forwarded your words to a friend who says of her passed-on husband, “I don’t want to stop grieving, because then he would be gone.”

I am glad you and Jim are still here.

What a nice tribute to your father. Being able to understand his relationship with God, as a God of grief, would make him very happy.

Beautiful, emotional and relatable.

Tonya: Very meaningful remembrance of your daddy. I feel your life in your writing. I feel your love for your daddy in your writing. Thank you.

I haven’t opened the Zephyr for a while — this was the first time in months, maybe in 2021 — but I was moved by this piece. The title grabbed me immediately, and everything that followed resonated deeply with my own thoughts and journey. Thanks for sharing, Tonya.

Nice account of your father and his beliefs. The reality is from your description he was closer to biblical truth that the Ecclesiastic Hierarchy of most Churches clergy. Interestingly, Jesus worst enemies which eventually caused his death were religious clergy and not secular authorities. The secular authorities only became involved out of fear of the Clergy’s influence on the people. Very little about most all of the existing Churches today is a reflection of original Christianity of the bible or what Church leaders label with the derogatory term, “Primitive Christianity.” As if somehow centuries later Christianity became more enlightened and sophisticated than when even Jesus Christ himself was on the Earth.

I’ve never been one who fancied religious rituals or ceremonies. If you research most of the origins of these, they have nothing to do with Christianity and actually come from other religious beliefs outside of Christianty. This is why when I was old enough to learn for myself and ressearch, I stopped celebrating Christmas from 1969 onward. It was actually instituted by what was left of the crumbling Roman Empire which became a Holy Roman Empire by fusing what was left of Christianity and pagandom into one new religion. Even the hellfire doctrine was not introduced until the year 600 C.E. or of our common era.

In any event from your dad’s experiences and beliefs, he seemed closer to the truth compared to not only the Catholic church but also all churches combined. Again, nice true life story.

Kevin

I understand. Thank you for the honesty of your experience.

Your essay about your Father, Christmas and growing up Catholic was beautiful.

You are an exceptional writer.

Thank You !!!

Great writing, thank you.