The man should have youth and strength who seeks adventure in the wide, waste spaces of the earth […]. The grandest scenery of the world is his to look at if he chooses; and he can witness the strange ways of tribes who have survived into an alien age from an immemorial past […]. The joy of living is his who has the heart to demand it.

—Theodore Roosevelt, 1916

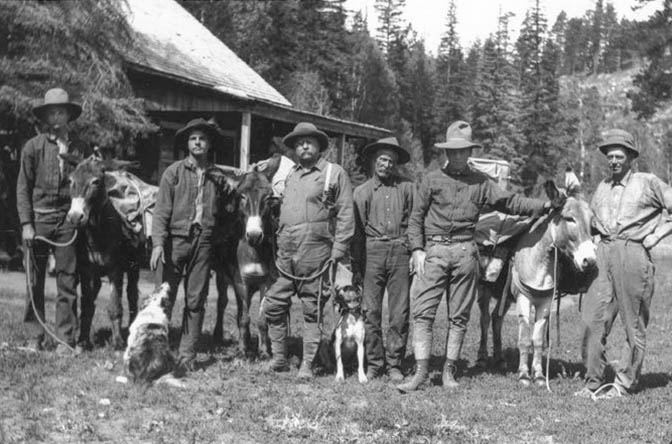

On July 13, 1913, fifteen-year-old Quentin Roosevelt peered into the depths of the Grand Canyon for his first time. He and his compatriots had just arrived by train at the South Rim, and they lost no time making their way to the edge to gaze into the awesome chasm. Leading the group was Quentin’s father, Colonel Theodore Roosevelt, who called the view “the most wonderful scenery in the world.” Also on the team were Quentin’s older brother, Archie, his second cousin, Nicholas Roosevelt, and a skilled outdoorsman named Jesse Cummins from Mesa, Arizona, who would serve as the head cook, packer, and horse wrangler for the long excursion they were starting.

The Colonel had visited the Grand Canyon ten years earlier during his first term as President of the United States. “In the Grand Canyon, Arizona has a natural wonder which is in kind absolutely unparalleled throughout the rest of the world,” he famously proclaimed. “I want to ask you to keep this great wonder of nature as it now is. I hope you will not have a building of any kind, not a summer cottage, a hotel or anything else, to mar the wonderful grandeur, the sublimity, the great loneliness and beauty of the canyon. Leave it as it is. You cannot improve on it. The ages have been at work on it, and man can only mar it.” In 1908, in his presidential capacity, he established Grand Canyon National Monument under the protection of the U. S. General Land Office.

Roosevelt’s notion of the canyon’s sublimity hearkened back to the Romantic idea articulated by eighteenth-century British statesman, economist, and philosopher Edmund Burke in his book, A Philosophical Enquiry into the Origin of Our Ideas of the Sublime and Beautiful. According to one of his interpreters, “Edmund Burke argued that the sublime is the most powerful aesthetic experience. It is a mixture of fear and excitement, terror and awe. It’s that spine-tingling feeling you get when you stand at the edge of a cliff. It’s a feeling of transport and transcendence, as you forget about your surroundings and are caught up in the moment.” Besides the thrill of encountering the sublime, Roosevelt believed that such experiences could provide rewarding opportunities for developing “nerve control” and “cool-headedness.” “Many things I feared, but by acting as if I was not afraid, I was not afraid,” he was quoted as saying. He hoped that the adventure would inspire Quentin to learn this lesson as well.

The Roosevelt party’s confrontation with the canyon’s sublimity would soon be multiplied many times over, as they were preparing to work their way into its very depths, then up the other side, as just the beginning of a rugged and arduous six-week hunting and camping adventure in the wilds of northern Arizona and southern Utah. The Colonel’s two years of ranching in North Dakota when he was in his late twenties introduced him to backcountry skills and hardened him to the rigors of outdoor life. That experience, and many others, had convinced him of the outstanding benefits of frontier adventures. “There are no words that can tell the hidden spirit of the wilderness, that can reveal its mystery, its melancholy and its charm,” he once expounded.

He intended to teach his youngest sons, Archie and Quentin, some key aspects of the rigorous and rewarding “strenuous life” that he had long practiced himself and advocated for others.

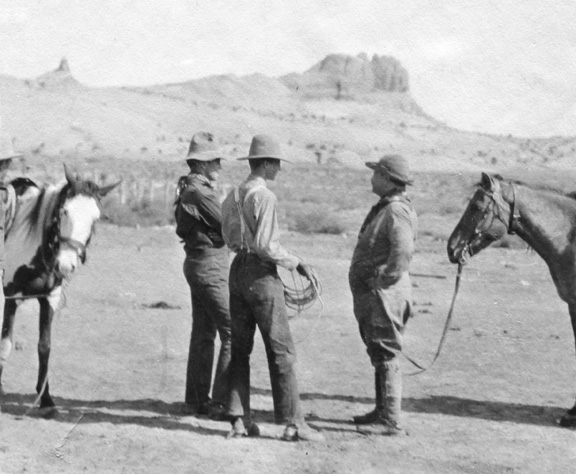

Archie, age 19, and Nicholas, age 20, were already adept at roughing it, having been trained in the western ranch lifestyle at the Evans School of Mesa, Arizona. Young Nicholas had just proven his mettle by scouting much of the rugged route on horseback, dealing with innumerable challenges along the way, and competently planning and arranging logistical support to make his uncle’s excursion a success. Quentin “had not before been on such a trip as that we intended to take,” remarked his father.

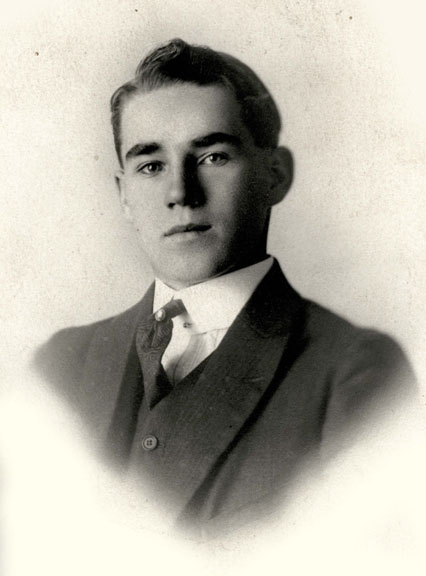

Quentin had the reputation as the mischief-maker of the White House during Roosevelt’s terms in office. According to his biographer, he was “the ringleader of a band of free-spirited lads known as the White House Gang.” When he was nine years old, he disrupted one of his father’s meetings with the Attorney General by roller-skating into the Cabinet Room to show off his pet king snakes. He was now a student at Groton, a prestigious prep-school, where he still engaged in occasional shenanigans.

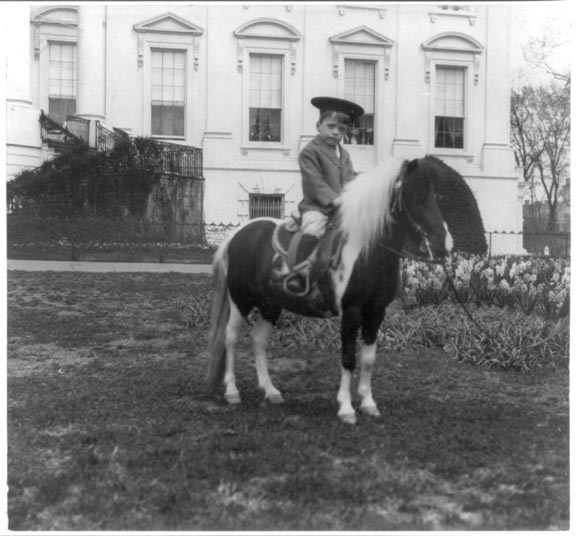

Quentin’s introduction to horsemanship had begun back in the White House days when he would take rides on Archie’s pet pony, Algonquin.

However, long-distance western horseback riding over rocky and steep terrain was a new experience for him, and likely somewhat scary. Theodore took Quentin on some practice rides on the canyon rim before their long descent.

Then, on the morning of July 15, the team mounted up and headed into the abyss. For the first segment of their journey, Nicholas had arranged with the Fred Harvey Company to provide mules to carry the men and their gear into the canyon’s depths. John H. Fleming, the manager of the Transportation Department, outfitted them and accompanied them down the trail.

Their first-day’s itinerary involved descending to the bottom of the canyon along the Cameron, Tonto, and Cable Trails; crossing the Colorado River on a cable car; and following a route up Bright Angel Creek by which they would reach the North Rim. Before crossing the river, they would relinquish their South Rim livestock, then meet up with another outfitter—the Grand Canyon Transportation Company of Kanab, Utah—on the north side of the cable car, which would have another set of riding and pack animals for them to use. These included two fine riding horses that belonged to Archie and two pack horses that belonged to Nicholas. Nicholas had brought them from Mesa, Arizona, to the North Rim country on his recently-completed scouting expedition. (On his way north, Nicholas had crossed the Colorado River at Lee’s Ferry, many miles upriver from the cable car crossing.)

Nicholas recalled the arrangements he had made with the Kanab outfit:

A copy of the agreement with the Grand Canyon Transportation Company dated June 23, 1913, which I have in my files, refers to furnishing us a guide and a cook, both mounted, and four first-rate saddle horses with pack outfit complete, together with food for the outfit for the period July 15 to August 2 inclusive. It was agreed that the outfit should meet us early on the morning of July 15 at the bottom of the Grand Canyon, on the north side of the Colorado River, where a hand-winch operated, suspended cable car had been installed a number of years previously.

To work out this agreement, Nicholas had spent time in Kanab negotiating with the company president, Edwin “Dee” Woolley, and Woolley’s son-in-law, David Rust, who was company foreman. Rust had been instrumental in construction of the cable car, the Cable Trail, which accessed it from the south; the route up Bright Angel Creek to the North Rim; and “Rust’s Camp” near the mouth of Bright Angel Creek, which was the predecessor of today’s Phantom Ranch. Nicholas distrusted both men.

Their final descent on the Cable Trail was particularly steep and treacherous, so they parted with their livestock and hiked—or slid—the remaining half-mile or so down to the cable car (which was at the site of the current-day Black Bridge). “It started to rain, and by the time we reached the river, there was a booming thunder storm in progress,” reported Nicholas.

Of greater consequence than the weather was the failure of a representative of the Grand Canyon Transportation Company to be there to meet them. They faced the dilemma of getting across the river on their own and then being without their livestock and supplies that the outfitter had agreed to bring. Would they have to turn back?

Fortuitously, a man who Nicholas did not immediately recognize appeared on the other side. They piled into the car and signaled him to winch them across. “I noticed the cage went very slowly and irregularly—stopping for a minute at a time,” Nicholas recorded. “And I couldn’t imagine what was wrong. The thunder re-echoed and boomed almost steadily, as we hung fifty feet above the roaring river.” Quentin undoubtedly had many thoughts running through his head as they hung suspended above the “rushing, muddy torrent of the Colorado” with the clapping thunder, lightning, and rain adding to the ambience and the fate of their excursion up in the air.

When they finally reached the other side, they met “an old man, exhausted from the effort of cranking our cage across the broad river […]. He turned out to be the foreman of the Bar Z ranch, which ran cattle and buffalo on the North Rim.”

Nicholas then recognized him as E. M. Mansfield, and he happened to be there at the behest of his boss, Henry M. Stephenson. In an amazing stroke of good luck, Stephenson was coming down the trail just behind the Roosevelts and had arranged for Mansfield to meet him there to operate the winch. When Stephenson arrived, the Roosevelt party helped Mansfield crank the cable car to haul Stephenson and his party across the river.

Stephenson convinced the Roosevelts to camp that night at the nearby Rust’s Camp rather than continuing up to the North Rim that day. “Among us all we had food enough for dinner and for a light breakfast, and we had our bedding,” the Colonel wrote. “With characteristic cattleman’s generosity, our new friends turned over to us two pack-mules, which could carry our bedding and the like, and two spare saddle-horses—both the mules and the spare saddle-horses having been brought down by Mansfield because of a lucky mistake as to the number of men he was to meet.”

Quentin must have had a flood of feelings that evening as he reposed at the bottom of the Grand Canyon with its towering walls looming on all sides and the music of Bright Angel Creek to lull him to sleep.

Mansfield roused the campers at 1:30 a.m., and, after a light breakfast of graham meal mush and canned chicken, Archie, Nicholas, and Jessie began walking. Quentin and his father were selected to ride the two spare Bar Z horses. By noon they had all reached the rim.

On the cool, forested plateau, they proceeded three or four miles to the Grand Canyon Transportation Company cabin where they saw, in the corral, “a lot of horses harnessed.” Nicholas called out to Scott Dunham, the man who was supposed to meet them at the cable car. “He came out took one look—swore and got so mad he couldn’t see straight,” Nicholas recalled. “We brought him out to Cousin Theodore where he gave several different explanations insisting that the day was the fifteenth. It was of course the sixteenth—and when we told him that, he said he wasn’t to meet till the sixteenth—a lie—and so on. […] He was then requested to reappear the next morning to receive his ultimatum.” The ultimatum, which the Colonel must have conveyed in no uncertain terms, was that the firm was fired.

The Roosevelt party reclaimed their horses and provisions and proceeded to the cabin of “Uncle” Jim Owens, the esteemed, elderly, resident game warden. Owens graciously welcomed them, and the Colonel invited him to join their hunting excursion as a guest. “Wonderful old Uncle Jim—as perfect a gentleman as God ever made—supplied us with his dogs and his horses and absolutely refuses a cent,” Nicholas wrote.

Grand Canyon National Park Archive.

Theodore’s primary objective for the expedition was to give Archie and Quentin opportunities to kill cougars, which were plentiful on the North Rim. Owens had hunting dogs and was adept at using them, so their association with him was ideal.

“No one, but he who has partaken thereof, can understand the keen delight of hunting in lonely lands,” Roosevelt wrote. “For him is the joy of the horse well ridden and the rifle well held; for him the long days of toil and hardship, resolutely endured, and crowned at the end with triumph.”

One of Roosevelt’s biographers summarized his great interest in hunting, which bordered on an obsession:

In the heat of battle or while killing large animals, he simultaneously experienced what he termed a “hideous horror” and “the hot life of feeling,” which alternately frightened and exhilarated him. Sometimes he drew back when the vehemence of these feelings frightened him. More often, however, the violence of hunting and soldiering was just fun, and he couldn’t get enough. He said he was more alive during those times that at any other.

The Colonel had planned the lion-killing trip as an important learning experience for his sons. He believed that it would help develop them into the kind of men he thought they should be—masculine, aggressive, courageous, tough, and unafraid to kill. Hunting, he said, “is a craft, a pursuit of value in exercising and developing hardihood of body and the virile courage and resolution which necessarily lie at the base of every strong and manly character.” Theodore had already taught the boys’ older brother, Kermit, this lesson in 1909 by taking him on an African safari. The two Roosevelts shot 512 animals on that trip.

On their first day of hunting on the North Rim, they had success. Roosevelt described the scene when the dogs treed a cougar:

It was a wild sight. The maddened hounds bayed at the foot of the pine. Above them, in the lower branches, stood the big horse-killing cat, the destroyer of the deer, the lord of stealthy murder, facing his doom with a heart both craven and cruel. Almost beneath him the vermilion cliffs fell sheer a thousand feet without a break. Behind him lay the Grand Canyon in its awful and desolate majesty.

A rifle was thrust into Nicholas’s hands, and he brought the lion down.

A few days later, Theodore, Archie, and Uncle Jim took the hunting dogs out again to search for more prey. Quentin’s horse had gone lame that morning, so he was unable to join them. After considerable time and toil, they met with success. Archie bagged a cougar, and a second one, which would have been Quentin’s had he been there, was killed by Theodore.

Still hoping to find an opportunity for Quentin to make his own kill, the hunters moved their camp to an extraordinarily sublime spot called Cliff Springs. Theodore described the scene:

From the southernmost point of this table-land the view of the canyon left the beholder solemn with the sense of awe. At high noon, under the unveiled sun, every tremendous detail leaped in glory to the sight; yet in hue and shape the change was unceasing from moment to moment. When clouds swept the heavens, vast shadows were cast; but so vast was the canyon that these shadows seemed but patches of gray and purple and umber. The dawn and the evening twilight were brooding mysteries over the dusk of the abyss; night shrouded its immensity, but did not hide it; and to none of the sons of men is it given to tell of the wonder and splendor of sunrise and sunset in the Grand Canyon of the Colorado.

“Of all remarkable things I have seen in Arizona none can compare with it,” Nicholas declared. “And of all places termed ‘romantic’ none were ever even in the remotest way equal to this spot.”

Unfortunately for Quentin, no lions were seen in the area during their hunt, and it was now time to move on. From the Colonel’s perspective, the quest was still a success:

The free, self-reliant, adventurous life, with its rugged and stalwart democracy; the wild surroundings, the grand beauty of the scenery, the chance to study the ways and habits of the woodland creatures—all these unite to give to the career of the wilderness hunter its peculiar charm. The chase is among the best of all national pastimes; it cultivates that vigorous manliness for the lack of which in a nation, as in an individual, the possession of no other qualities can possibly atone.

These moral achievements were insufficient to quell Quentin’s disappointment with his unsuccessful hunt. Would he ever have another opportunity?

Grand Canyon National Park Archive.

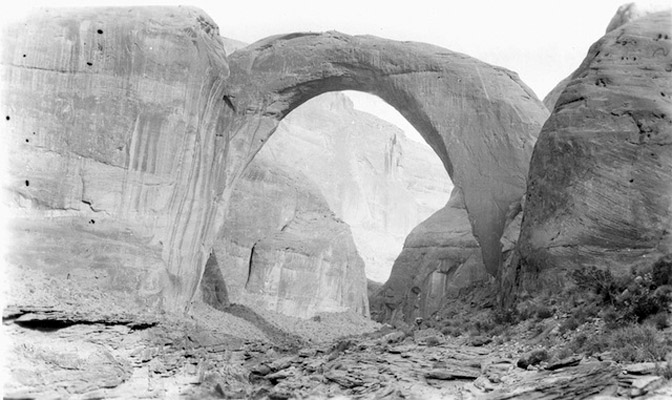

Part two of the Roosevelt expedition was an excursion to the beautiful and remote Rainbow Natural Bridge, nearly 100 miles to the northeast of their hunting grounds. In 1910, Theodore’s successor in the White House, President Taft, had designated the massive arch and the land immediately surrounding it as Rainbow Bridge National Monument, despite its isolated and difficult-to-access location in the rugged canyon country of southern Utah. The logistics for this portion of the trip were competently planned by the Colonel’s friend, the pioneer trader, J. Lorenzo Hubbell, of Ganado, Arizona. Hubbell arranged for another pioneer trader, John Wetherill of Kayenta, Arizona, to serve as guide and outfitter. Wetherill was my great-grandfather. I have told the story of the former president’s trip to the bridge elsewhere (“The President Slept Here: Theodore Roosevelt’s 1913 Visit to Kayenta and Beyond” in the August/September 2019 Canyon Country Zephyr), so I will focus here on the significance of that adventure to Quentin.

On August 1, the team “dropped down from Buckskin Mountain, from the land of the pine and spruce and of cold, clear springs, into the grim desolation of the desert,” providing Quentin with another notable encounter with sublimity. His father magniloquently described the scene:

The landscape had become one of incredible wildness, of tremendous and desolate majesty. The sullen rock walls towered hundreds of feet aloft, with something about their grim savagery that suggested both the terrible and the grotesque. All life was absent, both from them and from the fantastic barrenness of the bowlder-strewn land at their bases. The ground was burned out or washed bare […]. The cliffs were channelled into myriad forms—battlements, spires, pillars, buttressed towers, flying arches; they looked like the ruined castles and temples of the monstrous devil-deities of some vanished race. All were ruins—ruins vaster than those of any structures ever reared by the hands of men—as if some magic city, built by warlocks and sorcerers, had been wrecked by the wrath of the elder gods. Evil dwelt in the silent places; from battlement to lonely battlement fiends’ voices might have raved; in the utter desolation of each empty valley the squat blind tower might have stood, and giants lolled at length to see the death of a soul at bay.

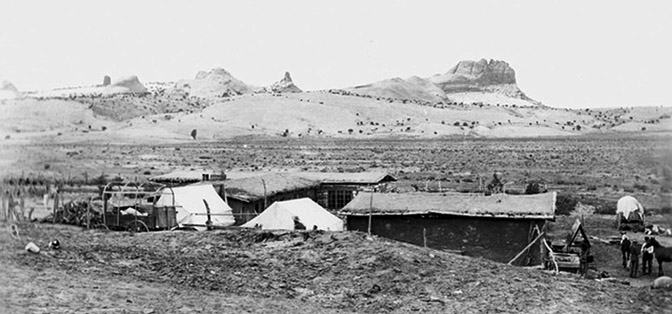

The Colonel’s account of their first night on the desert was similarly grandiose:

On the other side of the plain, two or three miles from a high wall of vermilion cliffs, we stopped for the night at a little stone rest-house, built as a station by a cow outfit. Here there were big corrals, and a pool of water piped down by the cow-men from a spring many miles distant. On the sand grew the usual desert plants, and on some of the ridges a sparse growth of grass, sufficient for the night feed of the hardy horses. The little stone house and the corrals stood bare and desolate on the empty plain. Soon after we reached them a sand-storm rose and blew so violently that we took refuge inside the house. Then the wind died down; and as the sun sank toward the horizon we sauntered off through the hot, still evening. There were many sidewinder rattlesnakes. We killed several of the gray, flat-headed, venomous things; as we slept on the ground outside the house, under the open sky, we were glad to kill as many as possible, for they sometimes crawl into a sleeper’s blankets. Except this baleful life, there was little save the sand and the harsh, scanty vegetation. Across the lonely wastes the sun went down. The sharply channelled cliffs turned crimson in the dying light; all the heavens flamed ruby red, and faded to a hundred dim hues of opal, beryl and amber, pale turquoise and delicate emerald; and then night fell and darkness shrouded the desert.

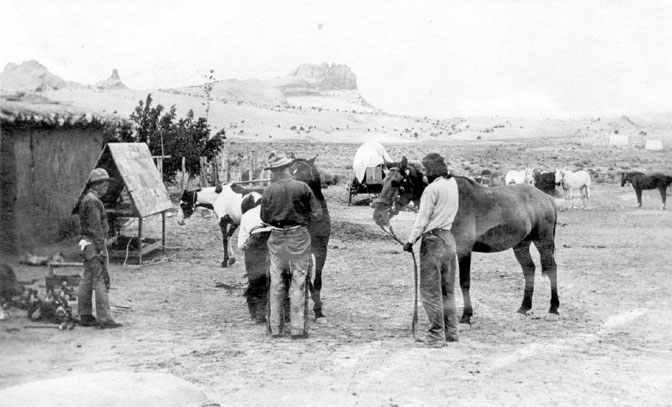

The next day, they proceeded to Lees Ferry, where, waiting across the Colorado River, there were wagons, mule teams, two guides, a cook, and supplies that Hubbell had sent out. Two of the men were Navajos. With their riding and pack horses and mules—many of them borrowed at this point—they felt they were in good shape to continue across the desert to Wetherill’s headquarters in Kayenta. It was “a scrap outfit, all right,” Nicholas proclaimed, but they were having a lot of fun. “For we were all joined together to have a good time, and to help out each other. Even Archie and I cooked and wrangled horses, and helped out as much as we could. Quent, too, took his share, consisting for the most part of carrying water.”

After a laborious, four-day drive across “a parched, monotonous landscape,” the adventurers arrived at Marsh Pass, which the Colonel described as a “wild and lovely” scene. Continuing on the next day, with no sign of any habitations in sight, the explorers rounded a hill and suddenly came upon the Wetherills’ delightful outpost at Kayenta. “Our new friends were the kindest and most hospitable of hosts, and their house was a delight to every sense: clean, comfortable, with its bath and running water, its rugs and books, its desks, cupboards, couches and chairs, and the excellent taste of its Navajo ornamentation,” the Colonel wrote.

John Wetherill, an experienced packer, guide, and outdoorsman, provided several of his own riding and pack animals that he knew could get them over the rugged, seventy-mile route to the bridge. Of significance to Quentin was the decision to include John’s sixteen-year-old son, Ben, on the expedition, and he and Quentin hit it off well together. Ben had grown up on the frontier; spoke the Navajo language fluently; and was savvy with livestock, camping, and all sorts of outdoor challenges.

Roosevelt’s schedule for the Rainbow Bridge portion of the trip was tight because, afterwards, they hoped to reach the Hopi mesas in time to see the annual Snake Dance. They heard that it would take place around August 22. They made quick preparations for the pack trip and were ready to go on the morning of August 10. In addition to Ben, John Wetherill included in the entourage a Navajo wrangler named Glad Hand and the renowned Paiute guide, Nasja Begay. Interaction with Native Americans was undoubtedly another learning experience for the young Quentin.

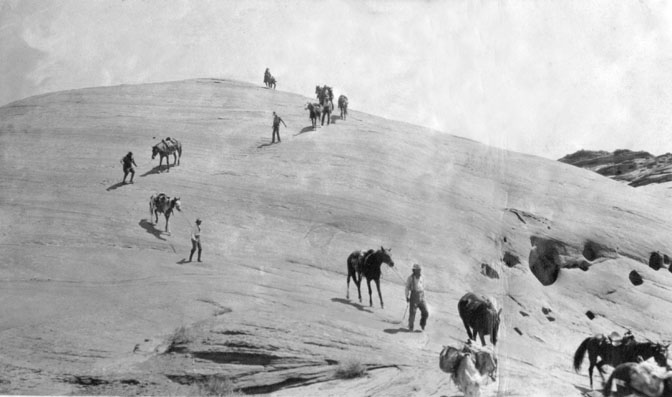

Wetherill’s trail to Rainbow Bridge involved a different type of horsemanship than Quentin had ever experienced. Long days in the saddle over steep and rocky ground required stamina and fortitude of riders as well as the horses. In several risky places, it was prudent to get out of the saddle and walk, lest a fall harm both horse and rider.

The marvelous environment more than compensated for the hardships, however. Nicholas took a stab at expressing the wonder of the scenery:

To describe it is impossible. A novelist would have it that before us, “lay a broad expanse of the most wonderful scenery in the world. It was the Creator’s Masterpiece of architecture. On all sides rose domes and mosques, eminences, pantheons, towers, cathedrals and spines strikingly carved out of the natural red sandstone. It was a sight that caused the spectators to draw in their breath sharply, and gasp in speechless admiration, etc. etc. etc.”

Intense travel and camping situations and his father’s counseling were effectively a crash course in backcountry skills for the young Quentin. Additionally, he gained confidence in dealing with unexpected challenges. John and Ben Wetherill served as role models as well.

After three days of strenuous travel, the adventurers rounded a bend in the canyon and got their first glimpse of the spectacular Rainbow Natural Bridge. They camped directly under it that night. “I don’t believe there is a more wonderful site anywhere on the globe than this Bridge,” Nicholas declared. “It is surely one of the wonders of the world,” the Colonel proclaimed.

The return trip took the party back to Kayenta, where they rested for a day and a half. Then they rode south on a three-day journey to Walpi, Arizona, where the Hopi Snake Dance was about to begin.

The sights and sounds of the Hopi Indian rituals at Walpi were otherworldly. The Roosevelts were invited into the priests’ sacred sanctum—an underground kiva—to attend a snake-washing ceremony. In the room were twenty men, forty to fifty deadly rattlesnakes, and many more snakes of other species. “I have never seen a wilder or, in its way, more impressive spectacle than that of these chanting, swaying, red-skinned medicine-men, their lithe bodies naked, unconcernedly handling the death that glides and strikes, while they held their mystic worship in the gray twilight of the kiva,” the Colonel wrote.

Later that afternoon, the Snake Dance took place. It was open to the public, and throngs of onlookers crowded the plaza where it was held. The presence of an ex-president in the audience was almost as exciting to many of the audience members as the ceremony itself.

After the dance ended, Mr. Hubbell motored the Roosevelts to his home in Ganado, Arizona, and then to the train station in Gallup, New Mexico. On August 26, they were back in New York. Thus ended their seven-week grand adventure. They accomplished all that the Colonel had intended, except for his desire that Quentin kill a large animal.

To deal with that disappointment, Quentin and Ben Wetherill concocted their own plan. Quentin would return to the West on his own the next year, and he and Ben would go on a boys’ expedition to the mountains of Colorado to hunt for bears. Surprisingly, Quentin’s parents consented. Theodore had hunted bear in Colorado in 1904, so he could understand his son’s enthusiasm.

In the meantime, just over a month after returning to New York, the Colonel departed for a much more daring adventure—exploration of the wild Amazon River Basin. He and an older son, Kermit, descended the mysterious River of Doubt and were beset by a multitude of difficulties that nearly killed Theodore and permanently damaged his health. On this occasion, the strenuous life, which he had so strongly advocated in the past, miserably failed him.

On July 9, 1914, Quentin arrived in Gallup, New Mexico, by train. Ben reached town on the 11th with an extra riding horse for Quentin. Accompanied by Ben’s cousin, fourteen-year-old Kipling Wade, the three boys headed out to Ben’s home at Kayenta, Arizona—a four-day ride to the northwest.

Their next destination was the Florida River in the San Juan Mountains of southwestern Colorado, far to the east. Ben planned too aggressive a schedule, exhausting the horses as well as the riders. They then looked for a bear wallow that Ben had heard about, but they had no luck in finding it. No bears were seen.

They rode further east to the home of Ben’s uncle, Clayton Wetherill, who lived near the headwaters of the Rio Grande River above Creede, Colorado. To get there, they crossed the Continental Divide over Weminuche Pass. “That day was the longest day I have ever put in. In the line of excitement I mean,” Quentin wrote his mother. One of their mishaps was “a horse falling over backwards on a steep bit of trail.”

Clayton welcomed the boys but chided Ben for overworking his horses. They would be in no shape to get Quentin back to Gallup in time for his train ride home, so they arranged for him to embark on the spur line from nearby Creede.

In the meantime, Clayton loaned Quentin a horse, and the boys had a good time exploring the nearby mountains and fishing. “We went all over the country round there,” Quentin wrote his mother. “My but those mountains are wonderful. Creeks and streams and waterfalls all over the place. […] I have really had a peach of a time, though the first part was no joke, and, believe me, I’ve learned a lot.”

Despite their failure to even see a bear, Quentin and Ben had such a good time that they began thinking of another adventure for the following year. “I now know what kind of an outfit I am going to take next year, and how much, or rather how little there will be of it,” Quentin reported to his mother. “I also know that I am going to start at twenty five miles a day for the first part of the trip until the stock and, incidentally, myself get trail hardened. However, I’ll tell you all about my plans for next year when I get home.”

When Quentin returned home, his parents were pleased to hear his enthusiastic reports. “Quentin has profited immensely by the very hard trip he had in the South-western Rockies this year, which, in spite of all the hardships, he really enjoyed,” his father wrote. However, Quentin was having chronic back pain, which was diagnosed as two partially dislocated ribs. It had been caused, the family learned, by an accident somewhere along the way in which a pack horse slipped and rolled onto him.

The family was opposed to Quentin heading out on another hunt in 1915. “I am having quite a row with my family now,” he wrote Ben. “They don’t want me to go out West again next summer—say I have been two years in succession and that is enough. I’ll write you more about it when I see them again, at Christmas.”

In later discussions, Quentin was unable to convince his parents to change their minds. He wrote Ben again on March 11, 1915. “I am afraid the family don’t want me to go West this summer. You see, I think I am going to one of those military camps from July fifth to August eighth, and of course that would break up my summer too much to want to go out for a trip, as I would have to be back East by September tenth at the outside.” That is apparently the last time that Ben heard from Quentin.

Quentin’s new-found enthusiasm for the rugged outdoors is a testament to the power of the Colonel’s mentoring skills and methods. Most notably, he exposed Quentin to many thrilling encounters with the sublime that made the young man long for more. No doubt Quentin would have embarked on many more adventures if he had lived long enough to do so.

In the Colonel’s mind, the time had come for Quentin to learn about killing of another sort. According to one interpreter, Roosevelt believed that “[t]he joy of killing animals extended into the joy of killing humans. He describes shooting a Spanish soldier in the Spanish-American war and how he doubled up ‘neatly as a jack-rabbit.’ His regiment took part in the battle for San Juan Hill, a particularly bloody battle which he described as ‘the great day of my life.’” Quentin would receive military training and, when the time came, fight for his country.

The Colonel felt a special affection and responsibility for Quentin, who was now seventeen years old. He justified continuing to work at his paying job of writing books and articles only for the period needed to usher Quentin into independent manhood. “I don’t care to get into work that will take me beyond the time when Quentin, my youngest son, is launched into the world; but that won’t be for three years yet and I am anxious to work during those three years,” he explained to a correspondent. That would take him through 1918.

World War I was already underway. When President Wilson decided that the United States should enter the conflict, Theodore expected all of his sons to enlist. Quentin agreed to do so, dropping out of Harvard in his sophomore year

Quentin joined the Army Air Corps, learned to fly, and, early in 1918, was sent to France where he would soon join the fight. His captain, the famous air ace Eddie Rickenbacker, admired him but was concerned that he acted reckless when he was in the air.

Quentin was thrilled when he was airborne. “You get so excited that you forget everything except getting the other fellow,” he wrote his parents. He shot down his first German plane on July 10, 1918. Four days later, he was shot down and killed. He was twenty years old.

When the Colonel heard the news, he was devastated. He never got over the loss, and his health continued to fail. “Since Quentin’s death, the world seems to have shut down upon me,” he moaned. Dispirited, he died on January 16, 1919, at the age of sixty, less than half a year after he lost his beloved Quentin.

More than thirty years ago, Harvey Leake began researching the history of his pioneering ancestors, the Wetherills of the Four Corners region. His investigations have taken him to libraries, archives, and the homes of family elders whose recollections, photographs, and memorabilia have brought the story to life. His field research has led him to remote trading post sites in the Navajo country and some of the routes used by his great-grandfather, John Wetherill, to access the intricate canyon country of the Colorado Plateau. Harvey was born and raised in Prescott, Arizona. He is a retired electrical engineer.

Click HERE for more Zephyr articles by Harvey Leake.

TO COMMENT ON THIS STORY BY HARVEY LEAKE, PLEASE SCROLL TO THE BOTTOM OF THIS PAGE…THANKS. WE WELCOME AND ENCOURAGE YOUR INPUT…JS

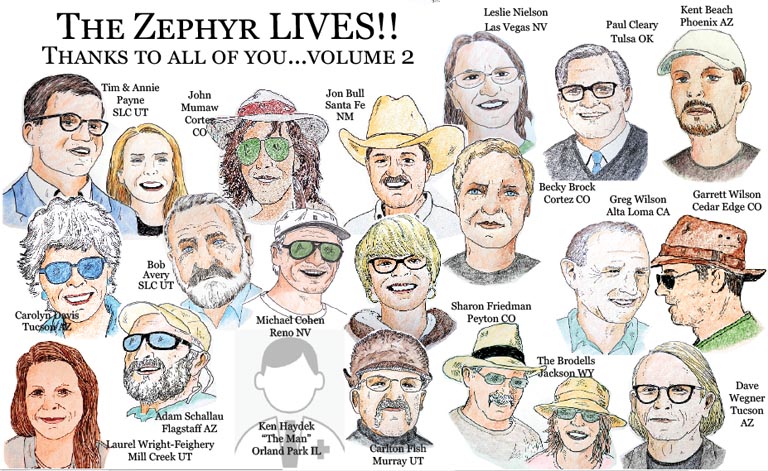

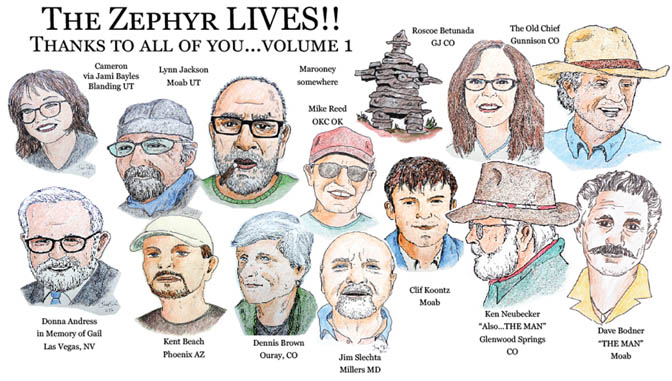

Thanks to them, our bills were almost completely covered.

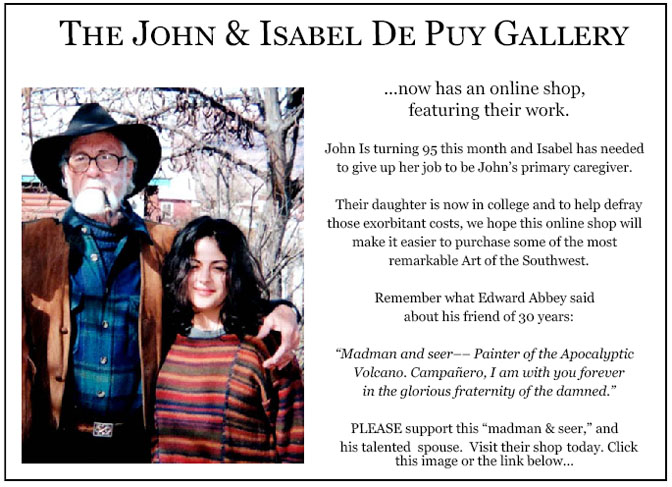

Now I’d like to return the favor. Check out the link below and their online shop… JS

https://www.depuygallery.com/shop.html

(The Unspeakable Crime & the Enduring Mystery—Looking for Answers) by Jim Stiles https://www.canyoncountryzephyr.com/2022/05/15/60-years-later-still-searching-for-dennise-sullivan-by-jim-stiles-zx8/

(My Recent Encounter with the Mental Health Industry

Jim Stiles

https://www.canyoncountryzephyr.com/2022/08/07/grief-meets-orwell-the-cuckoos-nest-by-jim-stiles-my-recent-encounter-with-the-mental-health-industry-zx20/

What a fascinating story! I was of particular interest to me as the Grand Canyon has always been my favorite destination since I first rode mules down from the South Rim as a 7th. grader! Can’t wait to read the article about Georgie White!

T.R.’s philosophy of life was instilled at Harvard. Studies taken told him of two ways a nation maintains their espirit de corps, doing actual war, and doing war against nature. Also popular there at the time was Harvard’s involvement in the eugenics movement whose philosophy has led to bioweapons to be used for political purposes.

——

Did not know that Kermit and Teddy shot 512 animals on their safari. No small wonder then that Kermit got embroiled in the geopolitics that continues to haunt us to this day. I am speaking of course to his involvement in the overthrow of the Iranian head of state.

Roosevelt: “I want to ask you to keep this great wonder of nature as it now is … ”

Dominy: “I have no apologies. I was a crusader for the development of water. I was the messiah.”

Hmm. Which one would you invite to your dinner party?

Eight billion and counting by tomorrow, stiles.

DO something !

What a splendid account — not only your quoted passages, but your own words and descriptions and the narrative thread. I have written a book about Theodore Roosevelt, and met Nicholas in my college days. Another hero of mine — George Herriman, creator of Krazy Kat, was also a friend of John Wetherill. I have some mementoes of a birthday party at Keyata, some drawings and doodles, at which Herriman and cartoonist Jimmy Swinerton (another Wetherill friend) were present.

Harvey’s articles are always so well written, informative, and entertaining. It’s good to see him in the Zephyr again.

awesome trip down the canyon with TR and the boys. sad, too, about Quentin’s fate. Having trod those trails myself, I especially liked the map that Harvey included. By the time I got there, they were all tourist trails, but I cannot imagine how the place itself could have been any less sublime. (Oh…well, maybe a gondola going down to the sipapu would perhaps ruin the vibe!)

I absolutely loved this article about TR and his sons. Quentin died too young as did so many young military through the history of this country and the world. Teaching Quentin to love killing led to his tragic early death. “There is no such thing as a good war, or a bad peace.” May the world declare peace and eliminate war.