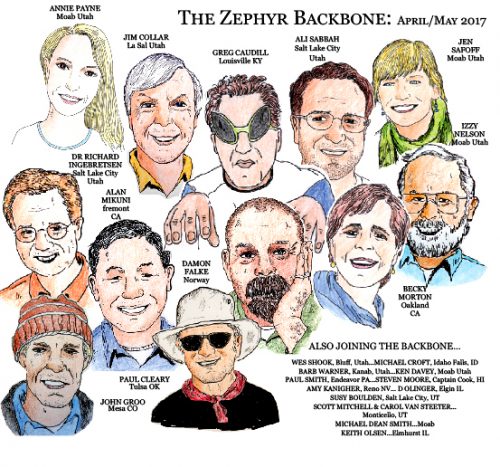

NOTE: Maxine Newell was a life long resident of the Colorado Plateau. She was born in Dove Creek, Colorado and lived in Monticello and then Moab until her death in 2015. Maxine and I worked together at Arches NP in the 1980s; she was one of the most interesting people i have ever known. Years ago, she gave me several stories she’d written about her ‘growing up years’ in Dove Creek and we’re happy to offer this first installment….JS

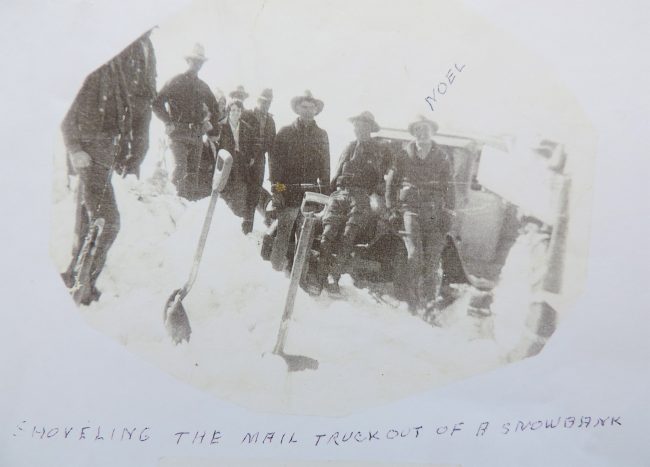

Trucking was just blazing its way into continental transportation in 1926 when the homesteading hopes of a couple of Dove Creek, Colorado farmers began to wane. They were Noel and Fendol Sitton. The two brothers had been eking out their livings on pioneer homesteads by subsidizing crop profits with rural school teacher salaries; they needed an easier way to make a living.

UP to that time, the Dove Creek country, now the “Pinto Bean Capital of the World,” was a virgin homesteading area which warranted little attention from the state. In 1926, persistent farmers won their first battle for recognition—daily mail service to the outside world.

The Sitton Brothers bid on a proposed mail route from Dove Creek to Dolores, Colorado, a D&RG railway terminal, and were awarded the bid. They pooled what assets they had to outfit their new business. Noel sold his preemption lands and contributed the promissory note he received for payment. Fendol put up a 1924 Chevrolet car. They swapped these assets for a Graham truck and a 1926 Dodge touring car, and they were in business.

“We didn’t expect to get rich on the flat $300 a month mail contract,” the Sittons reminisced as they looked back on their introduction to the trucking industry, “But we did have high hopes for an auxiliary business, freight and passengers.”

There weren’t a half dozen cars in the Dove Creek country then, and the nearest railroad center was at Dolores, 68 dirt miles away. The Sitton Brothers charged $3 per person for a round-trip ride on the mail truck; ladies and first-comers rode in the cab; the rest of the passengers rode in the back wedged between mail sacks and miscellaneous freight, braving dust, heat, rain, snow or cold from rural post office to rural post office along the way: Cahone, Pleasant View, Akmen, Yellow Jacket, and Lewis.

“Fendol took the first turn at the mail run, and we thought we had it made that night when he dumped $27 silver dollars on the table and split it two ways; $13.50 per day was plush living in the early days of the Depression. But the first day’s operation proved untypical,” the brothers reminisced. “We hadn’t calculated on the obstacle course—rains that turned the red clay road into a gummed bog. For three weeks after that first run, not a single motorized vehicle made it through the 68-mile strip, including the Sitton mail truck.”

One of the regulations of a mail contract was that the lock sack get through every day. During periods of impassable roads, Noel and Fendol stationed themselves at each end of the route. Each drove his vehicle as far as he could make it, then hoisted the first-class sack on his back and started walking. The two mail carriers passed each other enroute and kept on walking to the other’s wheels, and by this ingenious method, each brother could spend every other night in Dove Creek with his family.

The pioneer truckers admitted it was neither guts nor trucks that actually kept the mail going. They insisted upon placing the credit where it belongs: “to one of the best maintenance crews Colorado ever had.” The Conn Brothers worked day and night scraping snow, grading down ruts after a rain, and cleaning out 3-foot-deep ditches along the sides to prevent washouts. “We deepened every inch of those ditches shoveling out our four 30×5 truck tires.” Their second truck had dual wheels and hydraulic brakes and was much more efficient “after mechanics finally solved the air brake riddle.”

Freighting on the Dove Creek-Dolores line was something else. Sitton Brothers hauled everything offered, from a live pig or a crate a squawking chickens to farm equipment. One lucrative regular was the cream run. Farmers brought in their top cream in pint, quart, or gallon lots to the P.R. Butt store in Dove Creek, and other designated stations along the mail route. At these collecting places, it was poured into community 10-gallon cans for shipment to the Durango creamery. The Sitton trucks carried the full cream cans to Dolores, where they were transferred to the D&RG Railway line and thence to Durango via the “Galloping Goose,” a Cadillac car rigged with steel rail wheels. The contraption was dreamed up by Jack Odenbaugh. It loped right along on the narrow-gauge track and was more economical for small loads than the puffing steam engines. The Galloping Goose returned the empty cream cans to Dolores, and the Sitton Brothers trucks distributed them to respective stations. Once a baby shoe found in the cream was returned in an empty can for the owner to claim.

“That was the beginning of 20 years of trucking the hard way,” the Sittons noted. “It was the hardest, but probably the most contributing work we ever did. Farmers and villagers depended on that mail truck; we brought letters from home to the isolated settlers, carried clothing ordered from mail order houses, shopped for parts for broken-down farm equipment, and it wasn’t unusual to take time out to carry a scrap of fabric into a store to match it with thread for a seamstress in distress.”

Sitton Bros. Mail truck was the only outlet for farm produce in the Dove Creek area for many years. Everything was worth more than a cent-a-pound freight charge came their way. When the truck was too full of squealing pigs for the mail sacks, the two-family Dodge was pushed into service and the passengers got a break that day.

By today’s standards, some of the freight was a bit unorthodox. They hauled a lot of sugar for local bootleggers; once a complete still came by mail. “Luckily we always had the moral support of patrons and stores along the way. Everyone was always ready to lend a helping hand.”

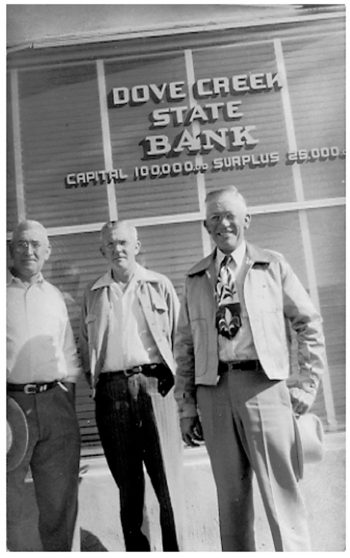

Eventually, the two brothers devised a more simple operating method; Noel moved to Dolores; Fendol operated the Dove Creek end, and they completed their contract in this manner.

It was a hard life, but the two brothers had been initiated into the trucking business and from that time on, they were to spend many years in the business. They were granted PUC permit No. 63. Colorado Governor Lee Knous, a long-time family friend who grew up in Dove Creek, where his mother still lived, advised them at the time the PUC permit was granted to hang on to it; it would be worth a fortune some day. The Governor proved far-sighted. PUC No. 63 was a granddaddy permit which gave the Sittons trucking rights anywhere in the state. But years later, when they concentrated operations in Utah, they let it go. “I never agreed with the principle of franchises,” Noel explained. “It always seemed to me that anyone should have free access to make a living.”

The Sittons maintain that early-day truck drivers deserve a place in western history along with fur trappers and river runners. They blazed the trails for what has developed into one of the nation’s greatest industries, and Noel and Fendol wished they could publicly laud all the boys who drove for them. Most have gone into business for themselves, and with success, “for those boys knew what it was to earn a day’s pay—Fred Allison, a real estate broker in Nogales; Dick Coleman, a successful rancher; and Ernest Parker and Glen Fisher and Bud Smith, and all the rest who kept those dual wheels rolling.”

“Railroads were flying high during that era, but partially because of trucking competition, poor management, union pressures, government subsidy of other transportation media, railroads are hurting today. This is too bad; they are needed now as never before. We can’t build roads fast enough to keep up with the trucks.” This was the Sitton Brothers’ opinion in 1970. “Anyway,” the brothers agreed, “those first truckers drove as the bush pilot flies—by the seat of their pants. They were their own mechanics; they loaded their own trucks and shoveled them out of the mire when they got stuck. Upsets? Sure, there were a few. But we never fired a driver for wrecking a truck. It invariably made him a better driver; his own neck was at stake too. Ernest Parker turned the mail truck over with his daughter and niece aboard.

‘Are you hurt?’ he asked from an upside-down position.

Finally he heard a ‘No.’

‘Then for hell’s sake, try to get out.’

It was nothing short of a miracle that they never had a driver injured, Sittons noted. “We didn’t even carry insurance on them; didn’t have to in those days.” They lost one truck in the Colorado River at Moab, Utah, and, luckily, Don Robbins, the driver, got out, as well as a customer and his son. Robbins was in shock and the first passerby found him running up and down the road like a mad man. The truck was completely submerged; a portion of the trailer stuck up. We lost a load of cement, a tractor, and finally, when it was extracted, we sold the truck as was for $1,000.” Robbins had missed the turn on highway 160 just before the road met the old Colorado River bridge at right angles. A new bridge was built later. “We always took credit for locating the bridge; it covers the spot where the Diamond T went in.” Noel added that his son-in-law, Hub Newell, was Utah State resident engineer on the new bridge project.

The Sitton Brothers recalled sending a truck to New Mexico after a load of oilcake; they got picked up for overloading. “We always overloaded in those days; just couldn’t stay in business if you didn’t, for the trucks weren’t built for profitable capacity.” Noel went to Farmington to bail the driver out of hock for $150. “We could have fought the charge, but we knew we would have the patrol on our tails thenceforth if we did.” Noel wrote a $150 check to the judge for the fine, and the judge gave him a receipt. “At least he meant to write a receipt, but he made a mistake and filled out a $150 check, properly signed. I always wondered what would have happened had I cashed it, but I sent it back to him. It was never acknowledged.”

Another driver was arrested at Pleasant Grove, Utah, once, for hauling without a permit. “We had been hired by the Blanding School District to bring in a rush of brick for a new school building. We depended on a loophole in the law when we took the job, which gave us the right to an occasional haul with a permit. Noel rushed to bail out the driver and faced a woman Justice of the Peace. “We hassled most of the morning over that loophole in the law and the $50 fine. Finally she decided the simplest way out was for us to put up a $10 bond and forfeit it, so that’s what we did.”

Fendol recalled an experiment that didn’t work: “We tried to go big time and corner the potato market. It turned out to be a bumper crop year everywhere; the price dropped and we couldn’t sell a sack. We had to put our trucks on a potato haul the next spring hauling thousands of sacks of rotten spuds out of storage sheds.”

Hauling cattle to market became a big part of their trucking business. It was the first time growers had an outlet for their livestock, other than driving them on foot to the Thompson railroad terminal. “It seems preposterous now that we didn’t know enough to put a stock rack on the trucks,” the trucking brother agreed. “But we had never seen one. We used to tie the cows’ heads down to keep them from jumping out.” Then, one trip, while Noel was unloading at the Salt Lake City stockyards, a man drove in with a high stake rack on his truck. When Noel returned home that night he drew it out on paper, and Bill Lindquist worked all night with him building a stock rack for their truck. The next morning, without an hour’s sleep, they loaded up with cattle and headed for the market with not a cow’s head tied down. Soon, enterprising truck firms were producing trucks with racks.

“We drove a lot in those days without enough sleep to be safe drivers,” Noel recalled. “Once, when my wife was with me, I stopped at the bottom of Price Canyon in Utah and turned the wheel over to her.”

“But I can’t drive a truck loaded with cows,” she protested.

Noel said: “You can drive better awake than I can asleep,” and she made it up the hill without mishap.

“You had to keep those trucks rolling when they were loaded with cows; in the summer it was too hot to stop; in the winter, they would have frozen.” Once, Noel and a driver were creeping up Price Canyon on icy roads; the driver was concentrating on the road; Noel got out of the passenger side to check on the cattle, and the driver ran off and left him. “He was a mile or two down the road before he missed me; he couldn’t back up the truck, so I had to walk.”

Maxine Newell was born in New Mexico in 1919 and moved to Dove Creek, Colorado a year later. She moved to Moab, Utah in 1948 and lived there until she passed away, in 2015. Click here to read our interview with Maxine from 1995.

Thanks for this article, it is very interesting to me as my dad Dick Coleman drove truck for Noel and His brother for many years out of Monticello. I only met Noel I believe one time as I installed his phone I his double wide trailer in Momticello. I think the double wide is still there. He told me that he really loved my Dad, and I told him that my dad had told me lots of stories about driving for him, it was cool.

My dad, Travis Barber, drive for the Sittons for a short time. Hauled grain and beans to Texas, but hated hauling cattle.

I remember my dad Harry C ROGERS talking about the Sitton brothers. Dad always had good things to say about them! Said they were good people n could be relied on! I think dad bought some property from them at one point on Bug Point and if I think dad helped them move to Dove Creek from Texas? I may be wrong on that tho!