Either you learn to love baseball as a kid or else you don’t learn to love it. Right? It’s just too big. It’s like any other behemoth cultural institution—Catholicism, for example. I can speak to this as a Catholic. That religion contains so much history, so many minor characters and saints and intercessory figures, so much specialized vocabulary, an hour-plus of memorized liturgy, not to mention the Stations of the Cross and the Rosary, and so many arcane rituals of behavior—stand, sit, kneel, stand again, kneel again–that only a child’s mind, with its bottomless storage capacity and its quick-firing synapses, could possibly accept the challenge of taking it all in. Any adult convert will always be a step behind the eight year-olds.

You should be baptized into the rules and practices of baseball when you’re still young enough to be over-awed and dwarfed by your surroundings. It needs to exist in the part of the mind that holds fantasy and mythology, and be wrapped up entirely in emotion—the placing of your small hand into a big hand, leading you through the concrete passageway into the park. So that, for the rest of your life, your love with baseball is entirely wrapped up in your love for whoever led you there. For a lot of people, the big hands belonged to their fathers. And so tightly wound together are the two in many American minds, the father and the game, that they might halfway blend the father’s features with those of his favorite players—the serious mouth of Ted Williams, or the sparkling eyes of Whitey Ford. Whatever and whoever he loved about baseball, they love too, with the unquestioning, unblinking dedication of a true believer. That’s truly the ideal way to learn to love baseball. I’ve seen it a hundred times in other people.

I didn’t learn that way.

My father wasn’t into sports. Period. He wasn’t against them, but he wasn’t interested. Of the topics that bring him to mind instantly for me, none involve a bat, or a helmet, or a sailing ball. I think of him when I think of Tom Lehrer, Quantum Mechanics, meatball subs, tarot cards, semi trucks, tap dancing… Catholicism is all woven together with my father for me, but not baseball. Granted, we lived in the middle of the forest in western South Dakota and we would’ve needed to drive quite a while to find a live game at the level of national drama. But no one in my family ever floated the idea of finding a local game or even turning to the sport when it aired on television.

Once, when I was already an adult and my parents had moved to California, the three of us (my mother, father and I) found ourselves at a Giants-Dodgers game. It was my mother’s idea, though my dad came along easily enough. She was the one who knew the game—from her childhood, of course. And so she answered our questions and narrated for us so that we could follow, albeit a half step behind, whatever was happening on the field. It was a good game, I think. The Giants lost, and this was fine. After all, Mom was still a quasi Dodgers fan at heart. She had learned about baseball in the normal way, by going to games as a little girl in Los Angeles. Her father had embraced the Dodgers when the team moved West, and so she did the same. And though her faith had lapsed over the years, she could still walk into a ball field after decades and pick it up again without effort. That’s what it’s like when you learn it as a kid. Easy.

It isn’t so easy when you come to love baseball as an adult, which is what I have tried, over the past decade, to do.

** ** **

Getting married requires a necessary dance of co-mingling and sharing interests. My husband Jim probably never dreamed that he’d be visiting so many donut shops or rummaging through so many thrift shops this past decade. Without me around, his playlists wouldn’t have shuffled continuously through so many early 90s singer-songwriters. But those things worked for him, and so he accepted them. And for my part, I found that quite a few of the things he loved—space travel, American history, and particularly baseball—worked for me. I discovered that the world became more interesting, and I became more interesting, the more I let him teach me about the things he loved.

To his credit, he started me on baseball slowly. I remember a warm, sunny afternoon when we still lived in Utah. We were each reading—separately, but in the same room—with the back door open and the screen door whistling with the light breeze coming through. He found a baseball game on the radio and let it play. Not loudly. It didn’t interfere with the sound of the birds outside, or the occasional rumble of a car passing on the street outside. It was a complement to all that. He said something like, “I always think a baseball game sounds like summer,” and I had to agree that it did.

After that, when I turned the radio dial in the car and found a game in progress, I’d leave it playing. And on occasional summer evenings, after we’d moved to Kansas, I would wander in and out of the living room to an accompaniment of the televised play-by-play. Jim’s isn’t an overwhelming devotion, thankfully. I would have struggled in one of those marriages where Sunday means Football, for example. I was allowed to come to the sport at my own pace—looking up from a book at his “Oh, would you look at that!” so that he could explain to me what had just happened on the screen.

Then we discovered a minor league team in nearby Wichita. The Wingnuts. A great name, if I’d ever heard one, for a town invested in the literal nuts and bolts of airplanes. Tickets were fairly cheap and, after a few years of slow acclimation, I was interested. I think I might have been the one who suggested we go.

The home of the Wingnuts, the Lawrence-Dumont Stadium, was its own draw. I had already guessed that I would like the feel of an old ballpark, and I did. I liked the location, on the banks of the Arkansas River (pronounced ar-KANSAS) in downtown Wichita. I liked the smell of the place—dirt and mustard. And the sound. The modest two-level concrete structure was capped with a small press box, from which the narrative of the game poured out over the stands as you watched. Built by the WPA in 1934, the place was still well-sized for the small city, even 80 years later. It easily held the local evening crowd of families and beer-drinking fans. Sitting in its stands, I felt that I was sitting in the tight kernel of the heart of the once-city. The city before it lost its focus in the expansion westward and eastward. I could forget the miles of paved-over farmland, cul-de-sacs, and big box parking lots we had driven past to get there.

Lawrence-Dumont was where I began to understand the game.

** ** **

It has a cadence, baseball. A neatly rotating formal structure suited to appeal to engineers and poets equally. Each inning builds through repetition and, once you’ve caught the tune, you won’t forget it. Within that unchanging architecture of the game, each at-bat presents an explosion of possibility. I found that I enjoyed the long silences on the pitcher’s mound, the glances toward the dugout, and the weighty moments before a throw. The tension, as the pitcher winds up. The slice and unmistakable crack of the wood when it touches the ball. The sigh of the stands when the batter fouls out yet again.

I was lucky to learn baseball via the minor leagues. For one thing, we didn’t need to save up for months to afford our seats. The bleachers were $8. And, for $12 a ticket, we could sit within spitting distance of the action. I never needed binoculars to figure out who was at bat. And I didn’t need the scoreboard to tell me whether the umpire had called a strike or a ball. When an outfielder leaped into the air and fell to the ground on a game-ending catch, I could see the pride on his face. If I’d been in the upper nosebleeds of the new Yankee Stadium, I doubt I would have felt the same connection.

And there was plenty to see. A plethora of strikes, near-catches and stolen bases, and enough foul balls to crack the car windshields of half of Wichita’s citizens. By the end of each game, the net over the stands behind home plate could’ve doubled as a playground ball pit. When a minor league team is playing lousy, they are really lousy. And when one guy is feeling hot, he can carry the team.

One Wingnuts game, in particular, sticks in my memory. It was late in the season, the summer of 2018. A sweet late-August kind of night, with bugs humming around the light stands and spider webs catching rides on the breeze. The game itself was slow. Six innings of slow. Jim provided his usual blow-by-blow for me: “Now, watch the pitcher. See how he’s—there, he almost picked off that guy on first.” But mostly, there wasn’t anything to describe. Our guys were down, 4-1. The score hadn’t moved since the second inning. I was beginning to think of the long drive home we’d be making in the dark, and wondering whether we shouldn’t beg out before the end of the game. I said something to Jim along those lines.

He nodded. “But let’s give it another inning,” he said. “Let’s just see what happens.”

And somehow, just because he’d said that, in the seventh inning things began to happen. First, one of our guys struck out. Typical. But then the second batter hit a single. Another guy struck out, and the crowd moaned. But then the next batter got on base, and advanced the other guy to second. A third batter hit his own single, and suddenly the bases were loaded. The eyes of the stadium fell on the next man to bat.

“He’s had a good game tonight,” Jim said. The young batter was scuffing his foot in the dirt, digging in and looking quietly confident. Not scared off his head, like I would’ve been.

“But that was playing defense,” I protested. I felt horrible for this kid, because he had made a couple nice catches from behind third base earlier in the game. No one would remember them, if this moment went sour. “This is…If he…” I didn’t even want to say it.

An entire stadium swallowed nervously in unison.

The boy at the plate steadied himself. He cocked his bat and looked up. The pitcher paused and then threw. A crack. And, on that first pitch, the ball sailed clear over the left field wall.

A couple of thousand people were standing before they knew they were standing. We were all yelling, without knowing what we were yelling. Four sets of feet touched the plate as we roared and danced around and hugged each other. And now—somehow! A Grand Slam! How did this happen?!–we were winning.

In the last two innings, the Wingnuts increased their lead. They took the night, 8-4, on the strength of that one kid at bat.

Jim and I drove home in the dark, having watched the whole game. We were laughing and still breathlessly energized, cruising along the empty nighttime highway, repeating that play for each other over and over again. “Oh, it was just PERFECT!” “And that moment, just before the pitch!” “Oh my god, what if we’d LEFT?!” We didn’t need the coffees we’d bought to keep our eyes open as we drove.

After that night, there was no question in my mind. I was a baseball fan. I’d groan through a thousand losses, and hold out through however many non-scoring innings. Whatever it took. I wanted to feel that again.

** ** **

The more I learned about baseball, the more I wanted to learn. I watched Ken Burns’ Baseball documentary, and was swept up in the romance of the whole sport. The magic of the Yankees in the late 50’s and early 60’s. The devastation in Doris Kearns Goodwin’s voice over the loss of her beloved Brooklyn Dodgers and Ebbets Field. Even though my mother would be among the new young fans for the team out West, I found myself aching for that loss.

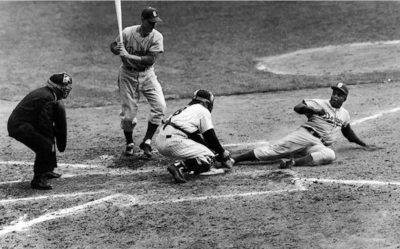

As an adult learner, I’ve had to bombard myself with the names and the teams quite a few times before any of it sticks. The big ones were easy—the over-the-top antics of “The Bambino,” Babe Ruth. The calm, reserved “Yankee Clipper,” Joe Dimaggio. Jackie Robinson, who could steal home and drive Yogi Berra crazy. Mickey Mantle, with that wide Oklahoma smile and loping run. I watched one old interview with Whitey Ford and now I’ll remember him forever thanks to the unreal beauty of his eyes. Others took repeated exposure—Pee Wee Reese and Willie Stargell. Henry “Hammerin’ Hank” Aaron and Pete Rose and Sandy Koufax.

Thankfully, I have an endless resource in my husband, who could list the starting lineup for the 1961 Yankees in his sleep. He still resents George Steinbrenner. He still loves Casey Stengel. He can recognize the big ballparks instantaneously–”See, there’s the Green Monster.” That means Fenway Park. If there’s ivy on the wall, it’s Wrigley Field. He’s still sick over the loss of Crosley Field, where he watched Cincinnati Reds games with his father. It’s from Jim that I know the Reds were briefly called the “Redlegs,” to placate tense emotions at the height of the Cold War. When he was a young boy, he took in a double header at Crosley between the Reds and the San Francisco Giants. In the first game, Reds’ pitcher Bob Purkey struck out Willie Mays four times. In the second game, Mays came back with two home runs and a double. Jim doesn’t need to look it up. Those games exist in his mind completely intact, eternally evergreen.

That reverence for baseball, and particularly for those golden postwar decades of the game, puts him in the company of an entire generation of Romantics. Not small-time romantics, mind you, but the big leagues. Some of the greatest writers of the past century were caught up in the same fandom. Just read John Updike on Ted Williams’ last game. Gay Talese on the retirement of Joe Dimaggio. Donald Hall on the Pirates. Jimmy Breslin on the Mets. It’s endless… Paul Auster, the postmodernist novelist, when searching for words to describe the period of his late adolescence, wrote, “I was still young enough to think that I had a legitimate shot at playing in the major leagues, but old enough to be questioning the existence of God.” It’s the game that planted the feet of literary men in the dirt, and lent grit and vigor to the most cloud-strewn minds.

As a reader, I could dedicate the rest of my life to only reading about baseball and never dip below the top-tier of American writers. The sport somehow marries fervent intellectualism with a grief-stricken and nostalgic kind of patriotism, and then stuffs its face with the world’s crummiest hot dogs. It’s that paradox—mustard and heartbreak—that gives it power. Surely it’s the only American sport that would have hired for its Commissioner a professor of English Renaissance literature.

Angelo Bartlett Giamatti (father of the actor Paul Giamatti) retired from his role as President of Yale University in the late 80s and dedicated the last five months of his life to overseeing the game he had followed so worshipfully since boyhood. When the poet and essayist Charles Siebert profiled the newly-elected Commissioner for the New York Times in 1988, he drew his piece to a close with this scene:

He [Giamatti] hunkers down on the ledge before him and looks out past the fences and parking lot and into the afternoon haze. ”None of us can go to a ball game, I think, without, in some way, being reminded of your best hopes, of your earlier times, some memory of your best memory. It’s always nostalgic even when it’s most vital and present. We shouldn’t be in awe of it, fall down in a heap about it. It’s not paradise,” he turns and smiles, ”but it’s as close as you’re going to get to it in America.”

Baseball as an earthly paradise. Say what you will about the man’s decision to ban Pete Rose, every institution in America should be run by someone who loves it so fiercely.

** ** **

But, in keeping with my lifelong habit of arriving at the party just as it ends, baseball isn’t now what it was when Pete Rose was still swinging a bat. Much less what it was for the childhoods of Paul Auster or Doris Kearns Goodwin or my own husband. The money is out of control. The heart just isn’t there. Ticket prices are higher than ever—or they were before the pandemic benched us all. Viewership keeps declining.

If baseball has given me anything, it’s given me something to be mad about that isn’t political. I live in Royals country, and the one thing that practically the entire state of Kansas can agree on is that the Royals are a disaster. We love them. We want desperately for them to succeed. Those two glorious seasons—2014 and 2015—were like a surprise cruise to the Bahamas for this part of the country. We couldn’t believe this was happening—to us? Are you sure?–and then the parades ended and we fell swiftly back to normal, which meant ceaseless complaining. What’s wrong with these guys? What could they be thinking? If you meet Royals fans in the summer months, they’re always happily tearing their hair out. It’s a pleasure. Truly. And besides, who else would we root for? The Rockies? That’ll be a cold day in hell, buddy.

Not to mention, one of the things I hated most about the Pandemic was that, overnight, it ended the sign-stealing scandal over the Houston Astros. I’m still angry about that scandal, and yes, I’d like to keep talking about it. I mean, really. These guys stole a World Series Title and they got, what, a fine? And Pete Rose is still persona non grata? Give me a break. And what about the Boston Red Sox? How did they skate through this thing so easily? And hardly anybody is talking about the Yankees doing the same damn thing since 2015. This is a HUGE deal, and it has the side-benefit of not having anything to do with national politics. But no, everybody’s so distracted by all this other stuff.

The big thing you would think I’d be excited about, now that the vaccination push is working, is the 2021 return of the Wichita Wingnuts season. And, on that, you’d be wrong. In fact, that’s the topic that gets me going worse than anything else.

Apparently, the big lesson I needed to learn about baseball is that it always breaks your heart. Always. I fell in love with the little concrete stadium next to the Arkansas River, and its plucky Independent League team, the Wingnuts. The team’s coach, interestingly enough, was Pete Rose Jr. And maybe that should’ve been a sign. Because in May of 2018, Wichita announced that it was cutting the Wingnuts loose. The city was looking for a bigger fish—ideally some AAA team, a good farm team for one of the big major league cities.

I was upset to hear we would lose the Wingnuts, but I could admit that, if we’d moved to Kansas a decade earlier, I would have happily watched the AA Wichita Wranglers’ games. And, yes, I would’ve been equally sad when that team decamped for Arkansas in 2007. A ten-year run, which is what the Wingnuts had in Wichita, is not so unusual for these minor league divisions.

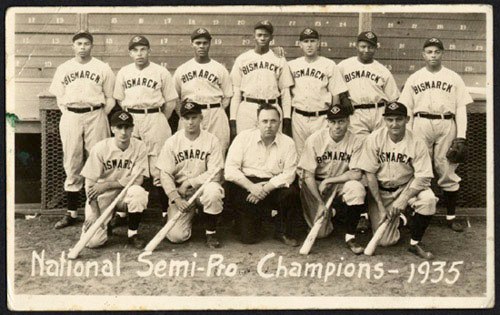

What made the 2018 announcement so painful wasn’t as much the loss of the Wingnuts as it was the loss of Lawrence-Dumont Stadium. This ballpark, mind you, had been consecrated by Satchel Paige, who struck out 60 batters and won four games on its field in 1935, a full thirteen years before he became the oldest player ever to debut in the major leagues. Wichita Eagle-Beacon Sports Writer Ray “Hap” Dumont paid $1000 to the famed Negro League pitcher to bring his integrated team from Bismarck, North Dakota for the first year of Dumont’s newly-invented “National Baseball Conference Semi-Pro Baseball Tournament”. Now they were razing the place to the ground. By the end of 2018, that modest WPA ballpark was a pile of rubble.

It’s a couple years and $75 million later, and the corner of McLean and Maple is now shadowed by the painfully mediocre “Riverfront Stadium”. Imagine a suburban office building that has inexplicably mated with a Buffalo Wild Wings. Actually, don’t try to imagine it, unless you’re hoping to fall asleep in the process. And the team that’s set to play there? The Wichita Wind Surge.

Wind Surge. Seriously. Say it a couple times, and cringe at how clumsy it is. The Wichita Wind? That would have been alright, and accurate. The Wichita Surge? It would’ve been lame, but still better. Wichita Wind Surge is awful. It takes only a seven year old’s sense of humor to find the joke in it. Locals were organizing Change.org petitions against the name within the hour it was announced. But apparently we’re trapped with it.

Not to mention, while everybody was distracted by the deadly virus sweeping across the planet, the MLB decided last year to “reorganize” the entire minor league system, and our ill-fated new team fell from AAA status, a farm team for the Miami Marlins, down to AA, under the Minnesota Twins. So much for landing a big fish.

Becoming a baseball fan has given me plenty to complain about. Again, at least it isn’t politics. For that, I’m grateful. But after all that complaining, our big question for next summer remains: will we go watch the Wind Surge?

The answer is, maybe. It depends on what the tickets cost.

** ** **

The thing is, you watch a baseball game for the players and how they play the game. Not for their stupid name. Not for their slick corporate stadium. And definitely not for the brand-new hokey monstrosity of a scoreboard overhanging the field.

If I go to a game, it’ll be to see whether anyone steals a base. (I really love it when they do that.) It’ll be for the seemingly-impossible catch, or the breakneck double-play. I’ll pick up on the patter of the conversations around us, and strain to hear the radio announcers calling the plays from up in the press box, and when I don’t understand something, I’ll ask Jim to explain it to me. That’s the best part, really.

I’ve loved each moment of learning about baseball, even when it’s driven me crazy. And somehow, even though I didn’t learn it as a child, I do feel nostalgic over it. I like to think of my mother sitting with the grandfather I never met, watching Sandy Koufax at the peak of his pitching career in Los Angeles. And I’ve found, somehow, in these years of learning the sport, that it does make me think of my father. The way he enjoyed humbling himself before a new topic he wanted to explore. The way he appreciated the process of learning. I remember how, at 60 years old, my Dad suddenly decided to learn to play the piano. The sound of his first cautious scales up and down the keys. He made such slow and patient progress over months with Fur Elise, practicing that one piece over and over, every day, until finally he had mastered it. I remember that the next day he turned a page and he began again, this time with a Chopin Nocturne. From him, I learned to enjoy the role of greenhorn. I learned to relish each small progression toward mastery—and even if you never reach mastery. All the better, really. And so my dad has become a part of my love for baseball, where I am still an amateur, even as a fan.

After the last painful year—the pandemic, and the loss of businesses and jobs, all the political fighting, and a death that rocked our family—I find that I’m turning toward this upcoming summer with hope. It will be green, if nothing else. And warm. I’m ready for long drives with the windows open, and ice cream cones. Tall glasses of limeade. Baseball. Yes, especially baseball. I want to sit out on the porch, with that late day sticky heat waning toward a soft summer night, something cold to drink, and that sound of a baseball game pouring out from inside the screen door. That’s when the world will feel right again. Jim on the porch swing beside me and an echo of distant trucks rumbling down the highway. Neon humming on the movie marquee. All those stars just beginning to twinkle in the firmament. It’ll be the seventh inning. Two strikes, with the bases loaded and some fresh-faced kid up to bat. The pitcher is winding up for the throw. That moment, as the heart skips double-speed in anticipation, and then the swing of a bat through the air.

Tonya Audyn Morton is the former publisher & managing editor of The Zephyr. She is now the founding publisher/editor and frequent contributor to “Juke,” an arts and literature journal on Substack. Zephyr readers can access Tonya’s page here. And on Facebook.

To comment, scroll to the bottom of the page.

Zephyr Policy: REAL NAMES ONLY on Comments!

Don’t forget the Zephyr ads! All links are hot!

If you think the Wichita Wind Surge is an awful name what about the AMARILLO SOD POODLES!

Sod Poodles? The Amarillo team ought to be the Armadillos. It’s a no-brainer. Tonya, don’t be too hard on our Colorado Rockies. For one thing, they suck. For another, they’re not the ‘enemy’, just (hopefully) worthy adversaries. Well. At the moment, they’re as bad or worse as your Royals. They gave away the best third baseman in the league, for Gawd’s sake! One of the highlights of my own life was the first game I ever played third base (little league). The other team must have known (spies? little league?) because the first three batters bunted down the third base line. I threw’em all out! Such a proud moment… bring Jim to Denver this summer and we’ll meet ya at Coors Field for a cold one and a hot dog.

OK Tonya. You are responsible for me not getting my normal amount of sleep tonight. I stayed up way past my bed time reading your very interesting article about baseball. That was after reading two attention grabbing articles about the big fire in Moab. No wonder Jim loves you. You write as well as he does and offer an interesting counterpoint to him.

Great story. I’ve loved baseball all my life. Grew up in New York, so still love those damn Yankees. The Mick was in his prime, and I could switch-hit by the time I was three. The modern professional game leaves me a little cold. Whereas there used to be actual teams and loyalty, it is now just business and a bunch of mercenaries, Way too much money, and they have forgotten how to play the game. How can you not know how to advance a runner, or be able to bunt, or be able to poke one through the empty side of an infield playing a shift?? How can these pitchers making $100 million, not be able to last more than 5 innings?

The minors is where the fun is, all the way down to the Grand County Red Devils and little league games.

Great essay! Have you noticed how it’s hard for people to leave a comment without evoking their own memories? Funny how this game can get into the long-term memory banks more than most. So, here goes. My favorite memories of Lawrence – Dumont Stadium. 1) hearing Dad tell stories about being an usher for the AAA Wichita Indians in the early 1950s, when the great Cleveland Indians players were passing through. 2) visiting Wichita in the early 1970s and going to see the Wichita Aeros play as, at first, Cleveland’s AAA team. Only as an adult could I get the double entendre of the Aeros nickname (aeronautics, of course, and something that goes with Indians). 3) taking Dad to one more game at the old stadium before they both were gone. It’s easy to have regrets in life, but time spent with a loved one at the ballpark is always special.

Visited Yankee Stadium many times during the 1950s-1960s: Mickey, Yogi, Whitey. The memories –good and bad– still resonate. I loved Yogi.The Center field bleachers were my favorite place to sit, right where Mickey would come up to the wall and give us a wave. The saddest event, however, came in the Summer of 1962. At one game Roger Maris was booed every time he stepped up to the plate, and I think you all know why that was. If anyone ever dared to tarnish the Babe, Mickey was the chosen one to inherit that legacy. But poor Roger did not realize at the time that his feat of 61 in ’61 would put him on the Public Enemy Number one list in the City.