If I had influence with the good fairy who is supposed to preside over the christening of all children, I should ask that her gift to each child in the world be a sense of wonder so indestructible that it would last throughout life, as an unfailing antidote against the boredom and disenchantments of later years, the sterile preoccupation with things artificial, the alienation from the sources of our strength.

—Nature writer Rachel Carson, The Sense of Wonder, 1964

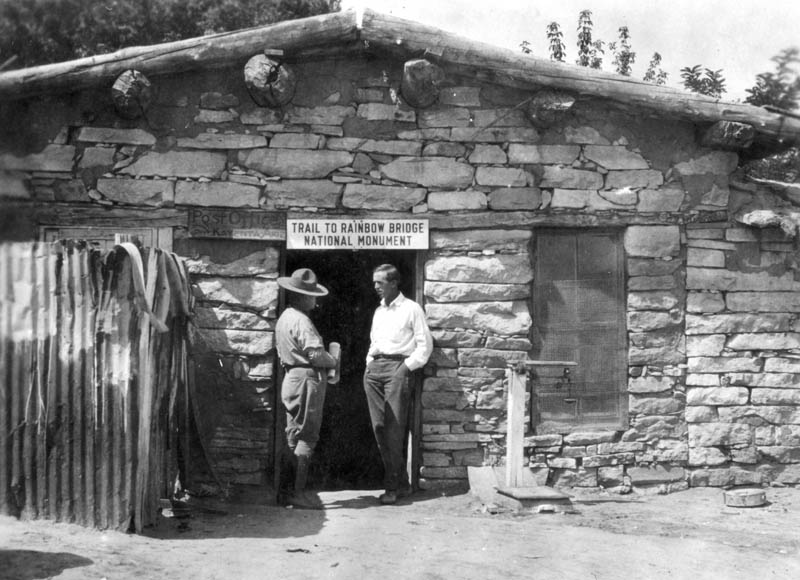

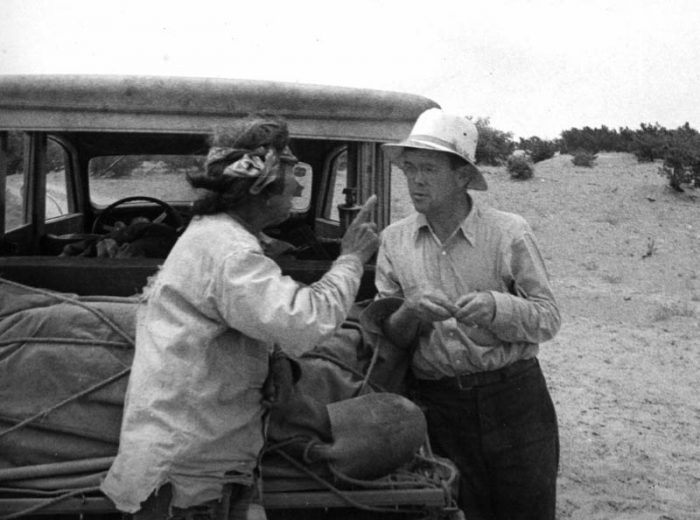

James Swinnerton, the pioneer California artist and cartoonist, first visited the Monument Valley area in 1920. He lodged with my great-grandparents, John and Louisa Wetherill, at their Kayenta, Arizona, home and became fascinated by the scenery as well as the local residents.

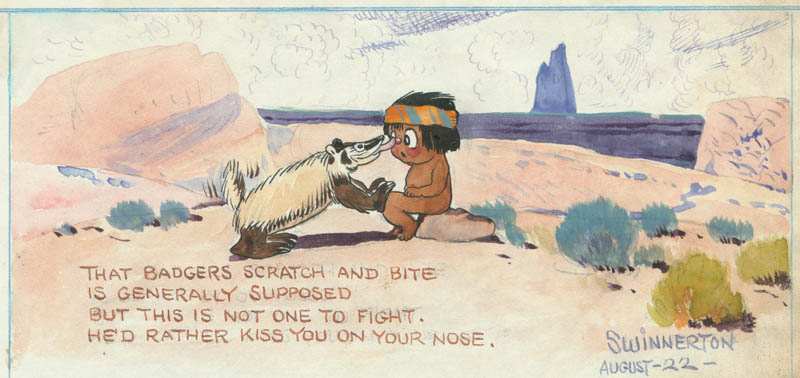

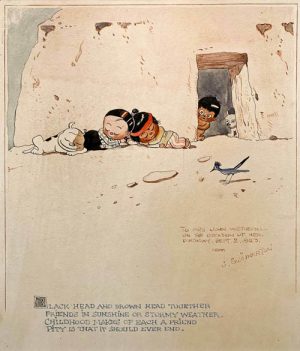

Swinnerton was inspired to begin a series of cartoons he entitled “Kiddies of the Canyon Country,” which involved sketches of cute Hopi and Navajo children, most often interacting with animals under interesting circumstances. He included rhymes to explain what was going on. “The little Indians were the ideal illustrations of children’s natural kinship with Nature, for from birth they are taught that creatures of the wild are their brothers, and are not to be feared,” he said. “Thus it was wholly logical for the Kiddies to meet and play with every kind of bird and beast that lived in their homeland, and to carry on their absorbing activities oblivious to the heat, cold, drought, and awful storms that their white cousins were conditioned to dread.”

Swinnerton returned to Kayenta many times to glean new inspirations. In addition to his animal themes, he occasionally used his cartoons to reflect on relationships between the races. Impressed by the mutual respect between Louisa Wetherill and her Navajo neighbors, he presented her with an unpublished kiddie sketch to honor her role in those relationships.

Since the early days, Kayenta was the home of many real canyon kiddies. Few of today’s children share the privilege of their joyful interaction with uncorrupted nature, unbridled freedom to explore the countryside, and their sense of wonder at the plants, wildlife, and natural features they encountered right in their backyards. Their playground was the great outdoors; their toys were simple ones they made themselves out of sticks and rocks; and their pets included wild critters.

Long before the Wetherills moved into the area, and prior to the Navajo era, Ancestral Puebloans raised their children there. We can only speculate on the fun, adventures, enlightenment, and moral strength those youngsters gained from their outdoor experiences.

One of the earliest canyon kids of whom we have a written record was a Navajo boy who later became known as Wolfkiller. He grew up in the late 1850s and early 1860s and told of the pleasures and insights of his childhood. (For more on him, see my article, “The Path of Light,” in the February/March 2020 Canyon Country Zephyr.)

Early Navajo cultural tradition involved respect for children and trust in their capabilities. “During my entire sojourn among the Navajos I did not hear an angry word spoken or see a displeased expression of the face towards the children who were continually in evidence, and they were real frolicsome kids,” observed Suren H. Babington, a physician who visited the Kayenta area in the mid-1930s.

“The Navaho toddler is given self-confidence by being made to feel that he is constantly loved and valued,” wrote psychiatrist Dorothea Leighton and anthropologist Clyde Kluckhohn. Some of the outsiders who moved into the Navajo country learned to apply these wise principles to their own children, who were blessed to learn of the insights, joys, and wonders of nature from their native playmates.

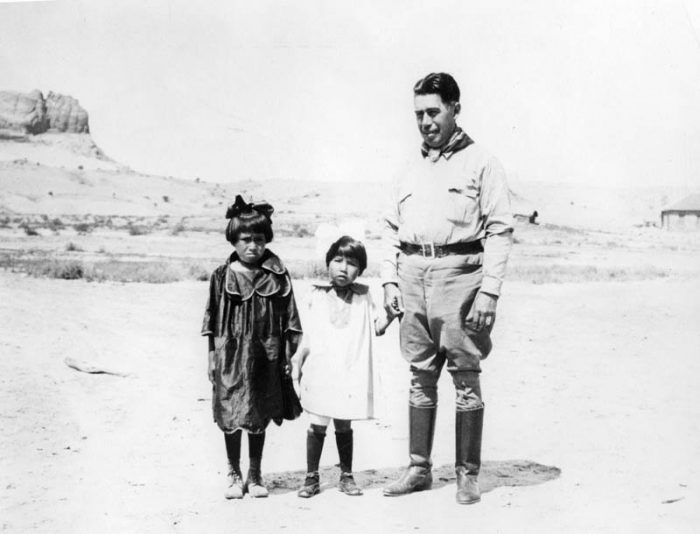

In 1900, John and Louisa Wetherill moved from Mancos, Colorado, to the wilds of northwestern New Mexico to live among the Navajo people. With them were their two children—Benjamin Wade, age three, and Georgia Ida, age two. The adults ran a trading post at a place called Ojo Alamo, and the children became friends with Navajo kids. According to writer Frances Gillmor, “The two white children rode out from the oasis, fearlessly and alone. They joined the children of the People, who followed their flocks day after day under the desert sun. They learned their speech; they played their games.”

Georgia’s name never seemed to fit her, and people began calling her “Sister”—a nickname that stuck with her for the rest of her life. The local Navajos also came up with their own names for the kids. They called Georgia Etai Yázhí, which means “Little Girl,” and Ben Ashkii Yázhí, which means “Little Boy.”

In 1904, disaster struck as Ben, who was then seven years old, was kicked in the face by a horse, smashing his face. His parents rushed him south to the railroad town of Thoreau and flagged down a train that took him to Albuquerque. There, a physician performed emergency surgery, which involved removal of an eye. Other than that loss, Ben eventually regained his strength, but, sadly, he was thereafter self-conscious of his facial appearance and lack of depth perception.

In 1906, the Wetherills moved to the then-remote Monument Valley area of southern Utah to start a trading post at the water hole called Oljato (Moonlight Water). Ben was nine, and Sister eight. Their journey was a long and difficult one—some 250 miles with the last half through roadless territory. The kids rode horseback. By that time, all of the family members were comfortable with life in the outback and familiar with the customs and language of their Native American neighbors. The children quickly became friends with the local kids and were adept at conversing with them in Navajo.

In 1909, young Salt Lake City artist Donald Beauregard came through Oljato with Professor Byron Cummings on an archaeological expedition and was particularly intrigued by Sister’s extraordinary depth of character:

“The most interesting feature of our visit here is the acquaintance of little Miss Ida Weatherell [sic], 11 years old, who has charmed our party with her vivacity and various talents. It is particularly instructive to hear her talk with the Navajos quite as unconcerned as she talks English, and to see how she is able to handle them to her liking. One might think to hear her talk that she is a matured young lady. She has gained the sense of responsibility that isolation only can give and at the same time she has kept her childish charms. “

In 1910, the family made their final move about 20 miles to the south across the Arizona line to a place they called Kayenta. The parents built another trading post and a house that evolved into a gracious guest lodge. There, down through the years, Ben and Sister met many notable visitors. Some of them, such as former president Theodore Roosevelt and novelist Zane Grey, used the post as a jumping-off place for horseback trips into the wild outback, which were outfitted and guided by John Wetherill. Louisa provided meals, lively conversation, and comfortable accommodations.

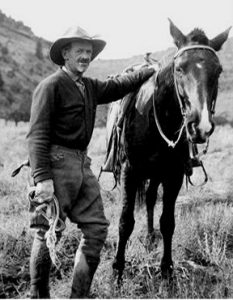

From the time Ben was a young teen, he participated in some of his father’s pack trips and quickly learned how to wrangle livestock, pack provisions, find routes and water sources, work his way through rough country, establish camps, and deal with dudes. When Theodore Roosevelt hired John to take him to Rainbow Bridge in 1913, Ben, who was then age 16, went along as a companion to TR’s 15-year-old son, Quentin. (For more on this expedition, see my article, “The President Slept Here: Theodore Roosevelt’s 1913 visit to Kayenta and Beyond” in the August/September 2019 Canyon Country Zephyr.)

In 1915, Quentin came back out west on his own, and he and Ben went on a bear hunting expedition to the headwaters of the Rio Grande River above Creede, Colorado. No bears were seen.

Living in a remote area, the Wetherill kids had no opportunities to attend schools. Their parents hired tutors, some of whom lasted only a short time due to the rustic living conditions. Nevertheless, Ben and Sister studiously mastered a good number of subjects. In about 1919, they enrolled in the University of Arizona at Tucson and began coursework in archaeology. They studied under professor Byron Cummings, who had been a family friend and house guest since 1908.

During the summer of 1920, Ben and Sister participated in Cummings’ archaeological field school. The team conducted excavations at two pueblos south of Navajo Mountain—Red House and Yellow House. After returning to Tucson that fall, the young Wetherills gave talks at the meeting of the Archaeological and Historical Society of Tucson. Ben titled his presentation “The Trials of an Archeological Guide,” and Sister’s was “The West versus the East.” After about two years of academics, they both left the U of A.

Sister Wetherill

Sister had met a man at the university named Victor Wallace Kilcrease, and they got married in Flagstaff in December 1921. They took jobs in Tuba City, Arizona, working for the Indian Service. The next generation of canyon kiddies began on October 3, 1923, when Sister gave birth to Juanita Louisa. The baby was thereafter called Johni Lou.

The Kilcreases moved to southern Arizona, but then returned to the Navajo country in May of 1925. Victor took a job delivering mail to remote post offices.

On July 10, 1925, Sister gave birth to her second daughter at her parents’ home in Kayenta. They named her Dorothy Lillian. She is my mother. The nearest doctor was many miles away, so the birth was attended by a Navajo midwife named Sue Bradley. From then on, Mrs. Bradley referred to Dorothy as “my daughter.”

As the kids grew up, they came to love their grandparents, the amazing environment in which they lived, the wild and domestic animals there, and the other Kayenta kiddies. Their characters, personalities, and temperaments were profoundly shaped by the interesting experiences they had.

In November 1926, the family moved to Parral, Mexico, and then, in September 1927, to Victor’s hometown of Casa Grande, Arizona.

In late 1928, Victor took a job at the construction townsite for Coolidge Dam on the Gila River in southern Arizona. Perhaps Sister had been naïve in marrying him, because he no longer exhibited the kindness that she had come to expect from family members. She took the kids and left him, then filed for divorce.

In September of 1929, Sister remarried—this time to a local man named M. G. Adams. He was affectionate to her and the kids and gave their lives new promise. When work slowed down at Coolidge Dam, they bought a small farm in Mesa, Arizona, where Johni Lou and Dorothy could roam and romp with their pets and the farm animals. Sister got involved with her neighbors and tried, with little success, to teach some of them Navajo words. At every opportunity, they would make the long drive north to Kayenta for extended visits with John and Louisa.

On July 4, 1935, tragedy struck the family. Johni Lou rode the family horse, Smoky, in the Mesa parade, and, on the drive back to the farm, a drunk driver ran a stop sign and hit their car, killing Sister immediately. The girls were only slightly injured. Sister was 37 years old.

Ben Wetherill

After he left the university in about 1921, Ben began trading with the Indians on his own. He started a small store west of Marsh Pass, about 12 miles southwest of Kayenta. In 1923, He married Myrle Jeanette Davis, the daughter of William James and Mary Blanche Davis, who were school teachers with the Indian Service.

In 1923, Ben and Myrle moved to a very remote spot on Paiute Mesa some 30 miles northwest of Kayenta and opened a new trading post. It seemed that Ben wanted to get away from civilized society and live only with Native Americans. A visiting anthropologist observed that he “was allied biculturally, morally, intellectually, and emotionally with the Indians.”

“Ben was truly a great friend of the Navajos,” wrote Bert Tallsalt, a local man who deeply respected him. “He was a Navajo at heart.”

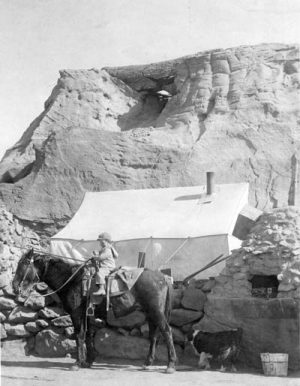

Paiute Mesa is surrounded by canyons, except for a neck of land that connects it to a broader area to the south. With great difficulty, Ben could bring in a wagonload of supplies across the neck, but he preferred to come up across Nokai Canyon to the east on a trail that “was rough, rocky, narrow, steep and slippery baldrock.”

Ben used burros as pack animals. “The donkeys brought the flour from over the ridge,” according to one observer. “There were about 12 donkeys and they each carried 3 – 25# bags of flour.”

The closest water supply was a small rain-collecting reservoir about two miles away. Ben hauled water from there in 55-gallon barrels in his wagon.

Tallsalt told of a problem Ben had keeping his glass eye in place. The local people, observing this, came up with a new nickname for him: Bináá’ Halts’id, which means “one whose eye fell out.”

When John Wetherill had more guiding work than he could handle, he often enlisted Ben to take clients into the backcountry. Typical of such expeditions was the 1926 William A. Keleher excursion to Rainbow Bridge. Keleher found Ben to be very capable, but sometimes cynical about city folks. “Introducing Ben Wetherill, Rainbow Trail guide,” he wrote. “Has a nervous chill when approached by writers, artists and poets. Knows many celebrities, but, in his own words, knows them too well.” However, when Ben learned that Keleher was savvy about the outdoors and livestock, the two men got along well.

Ben and Myrle began bringing their own canyon kiddies into the world. Milton Elwood was born on September 9, 1925. Three other sons would come later: William John on March 23, 1927, Benjamin Alfred on February 7, 1930, and Robert Lewis on August 29, 1931.

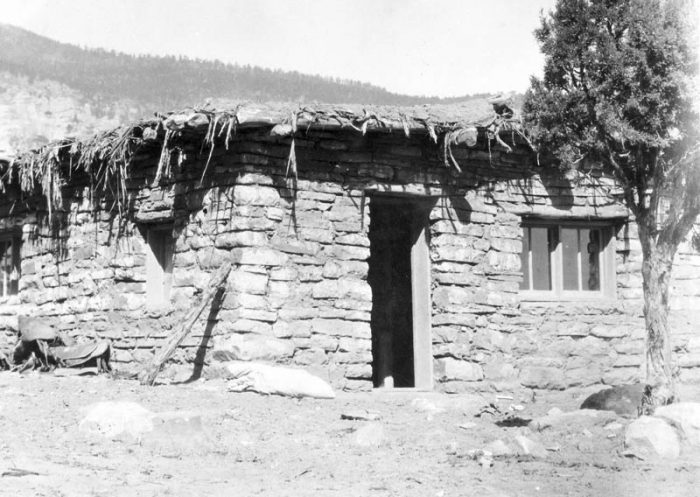

After a little more than a year of trading at Paiute Mesa, Ben and Myrle closed down their operation due to the difficulty of getting water. By 1927, they were living in a brush shelter at their “Cottonwood Spring Trading Post,” which was located west of Paiute Mesa at the southeast base of Navajo Mountain. There, access to supplies was easier and water was plentiful. A Navajo stone mason helped Ben build a trading post and the beginnings of a house. Ben also began construction of a tourist camp at War God Spring on the side of Navajo Mountain, but that operation never came to fruition.

In 1930, Ben provided logistical support to Byron Cummings on an archaeological dig just north of Cottonwood Spring. There he met Dr. Charles Van Bergen, a wealthy retired physician and benefactor of the Los Angeles Museum. Van Bergen and Arthur Woodward, curator of history at the museum, were planning other archaeological projects and enlisted Ben to help out. He accepted that position and closed down his trading post.

From 1930 to the fall of 1931, Ben worked for the Los Angeles Museum as archaeologist at the Grewe site in southern Arizona near Casa Grande Ruins National Monument. He then transferred to a dig at Gila Butte south of Phoenix. In March 1932, he was in charge of work at another site a few miles east of Tucson. He also helped Byron Cummings on the excavation of Kinishba, a large pueblo on the Fort Apache Indian Reservation in eastern Arizona. He continued his association with the Los Angeles Museum until 1935 as field explorer and archeologist.

During the summers of 1933 to 1937, Ben also worked with the Rainbow Bridge-Monument Valley Expedition under various titles such as Assistant Field Director. The expedition was an endeavor conceived by John Wetherill and implemented by National Park Service naturalist Ansel Hall to conduct scientific studies of the Glen Canyon, Navajo Mountain, and Rainbow Plateau region in the Utah/Arizona borderlands region in support of its designation as a national park. (For more on this, see my article, “The Early Fight for Glen Canyon and the Rainbow Plateau,” in the December/January 2019 Canyon Country Zephyr.)

From December 1933 to May 1934 and August 1934 to September 1934, Ben also directed archaeological work in Zion National Park in southern Utah for the National Park Service through the depression-era Civil Works Administration.

Ben’s involvement with these projects brought his remarkable character and abilities to the attention of some notable scholars and scientists. One such observer was Lyndon L. Hargrave of the Museum of Northern Arizona, who participated in the Rainbow Bridge-Monument Valley expeditions:

“Ben Wetherill, who had grown up on the Navajo reservation, spoke Navajo with great fluency: once he said to me that he could think more easily in Navajo than in English. […] Ben was young, vigorous and competent, and it was he who negotiated with the Navajo, got the mules arranged for the packers, and did the thousand and one other things without which the expedition could not possibly have been successful. Ben was an unusual man in many ways. He had a good formal education from the University of Arizona, he read widely, and he was deeply interested in archaeology, as well as in other phases of natural history. He also knew the country exceedingly well and was an invaluable asset to the expedition.“

Suren H. Babington, the expedition’s medical doctor for several seasons, was impressed by Ben’s affinity with the Navajo way of life: “Aski-Yazi, Little Man, as he is known among the People, is trusted by all. Having been brought up with the Navajo children, he speaks their language like a native. When he is with them, he conducts himself like a member of the tribe. He sits on the sand as they do and has even acquired some of their mannerisms.”

From 1937 to 1939, Ben worked as district supervisor for the Indian Service at Pinon, Arizona. In 1940 he bought the Pinehaven trading post, south of Gallup, New Mexico. While living there, marital conflicts resulted in a gun “accident,” necessitating the amputation of his left foot, and then Myrle left him and filed for divorce.

Ben volunteered for military service during World War II, but he was turned down due to his poor physical condition. Wanting to serve his country, he accepted civilian employment with the Guy F. Atkinson Company at Excursion Inlet, Alaska, in the position of interpreter for Navajo workers.

Ben returned to Arizona following the death of his father, John, on November 4, 1944. His mother, Louisa, died the following September. Depressed and destitute, Ben sought solace in alcohol. His remarkable life ended on July 15, 1946. He was 49 years old. His Navajo friend, Bert Tallsalt, assessed his profound sadness during his last days: “Perhaps he found himself between two worlds like some of us who have been away to school and find difficulties adjusting to both cultures. He may have never fully readjusted to his own culture.”

Betty and Fanny Wetherill

In 1917, John and Louisa Wetherill took an infant Native American girl into their home. Her name was Esther, the daughter of Mr. and Mrs. Joe. Her father was Navajo. Her mother was of Ute and Blackfoot ancestry and had been a captured slave before gaining her freedom and starting a family. She could not take care of the baby and asked the Wetherills to take over.

A few years later, Mrs. Joe flagged down the Wetherills as they were driving and told them of the cruelty of her husband. She begged them to take her second baby as well, so they did that. Her name was Francis Virginia, but she became known as Fanny. She was born about November 18, 1918, near Kayenta and lived with the Wetherills until she came of age. Sadly, her older sister, Esther, contracted tuberculosis and succumbed to it while she was still a young child.

In 1922, Sister Wetherill, who was working at the Bureau of Indian Affairs boarding school in Tuba City, told her parents of a young Navajo girl named Betty who was very unhappy there. “When just three years of age, by force I was taken from my native parents and placed in the disreputable Indian school at Tuba City,” Betty later recalled. “There, we were treated more like slaves than humans, and were forced to eat food comparable to slop, with an occasional rotten apple or pear.”

John and Louisa took Betty into their home as well, and she became another member of their family. She was seven years old, having come into the world near the Arizona/New Mexico border about June 15, 1916. They gave her the middle name “Zane” in honor of their friend, the writer Zane Grey.

On August 1, 1937, Betty married Cecil Howard “Buck” Rodgers, and they raised five canyon kiddies of their own. For many years, they owned and operated the Buck Rodgers Trading Post in Cameron, Arizona.

Fanny married Lutie C. Mahan on October 18, 1945. They raised four kids who were privileged to hear their mother’s stories of her early days. They lived overseas on various construction assignments before finally settling in Show Low, Arizona.

In their adulthood, the younger generation of canyon kiddies led their own interesting and productive lives and passed on their amazing heritage to younger generations. The impacts of their insights and perspectives on life are still being felt.

They say that society is ever-progressing and, through modern inventions and technology, humans are climbing the evolutionary ladder to an enlightened state of being. From some perspectives, however, so-called progress is really regress, and evolution is really devolution.

The prevalent philosophy of modern society is that, through intelligence and cleverness, humans can transcend nature and create a prosperous and gratifying artificial environment of manufactured possessions, machines, and gadgets to insulate us from the natural realm. This modern way of thinking has some dire unintended consequences.

In his book, The Disappearance of Childhood, social critic Neil Postman alleges, “The child possesses as his or her birthright capacities for candor, understanding, curiosity, and spontaneity that are deadened by literacy, education, reason, self-control, and shame.”

Psychologist Jean M. Twenge, in her book, IGen: Why Today’s Super-Connected Teens Are Growing Up Less Rebellious, More Tolerant, Less Happy—and Completely Unprepared for Adulthood, presents the results of her research into the debilitating effects of kids’ preoccupation with electronic gadgets. “[Teens] are at the forefront of the worst mental health crisis in decades, with rates of teen depression and suicide skyrocketing since 2011,” she writes. “Considering that teens spend about seventeen hours a day in school, sleeping, and on homework and school activities, nearly all their leisure hours are now spent with the new media. The hour and a half that’s left is used up by TV, which teens watch about two hours a day.” Interestingly, Twenge fails to consider the antidote of reconnecting kids with the wonders of nature.

Other authors have recognized the root of the problem. Most famously, Richard Louv does so in his book, Last Child in the Woods: Saving our Children from Nature-Deficit Disorder. Biologist George K. Russell comes to a similar conclusion in his book, Children & Nature: Making Connections. He writes, “Youngsters are programmed and scheduled, tested and retested, given little or no recess time at school, and pressured to get ready for higher levels of education. They have little or no experience of the joys of wandering, the vagaries of fantasizing or the simple pleasures of made-up games, unscheduled days and the carefree delights of summer.”

Traditional Native Americans, such as Wolfkiller, had deep insights regarding the essential teachings that nature can bestow on those who stay connected with it. Chief Dan George, of the Tsleil-Waututh Nation of British Columbia, characterized the modern problem as, fundamentally, a lack of love. “It is hard for me to understand a culture that not only hates and fights his brothers but even attacks Nature and abuses her,” he writes. “Man must love all creation or he will love none of it. Love is something you and I must have. We must have it because our spirit feeds upon it. Without love our self esteem weakens. Without it our courage fails. Without love we can no longer look out confidently at the world. Instead, we turn inwardly and begin to feed upon our own personalities and little by little we destroy ourselves.”

Those who seek gratification in artificiality cannot imagine the treasures they are missing out on. “Those who contemplate the beauty of the earth find reserves of strength that will endure as long as life lasts,” wrote naturalist Rachel Carson. “There is symbolic as well as actual beauty in the migration of the birds, the ebb and flow of the tides, the folded bud ready for the spring. There is something infinitely healing in the repeated refrains of nature—the assurance that dawn comes after night, and spring after the winter.” No doubt the canyon kiddies of yesteryear would agree.

More than thirty years ago, Harvey Leake began researching the history of his pioneering ancestors, the Wetherills of the Four Corners region. His investigations have taken him to libraries, archives, and the homes of family elders whose recollections, photographs, and memorabilia have brought the story to life. His field research has led him to remote trading post sites in the Navajo country and some of the routes used by his great-grandfather, John Wetherill, to access the intricate canyon country of the Colorado Plateau. Harvey was born and raised in Prescott, Arizona. He is a retired electrical engineer. Click here for more articles by Harvey Leake.

To comment, scroll to the bottom of the page.

Zephyr Policy: REAL NAMES ONLY on Comments!

Don’t forget the Zephyr ads! All links are hot!

Interesting, true thoughts on the negative effects of technology on youth of today, and nature as a proposed antidote.

The Wetherill family history included in this article has not been published anywhere else that I am aware of.

Very valuable history and insight into the ills of society today.

Thank you Harvey!

I read the article with great interest. I have a very, very distant connection to the Pinehaven trading post purchased by Ben Wetherill. Horace W. Smith moved from Oracle, AZ to Pinehaven, NM to operate a trading post, and he was for a time the Postmaster at Pineheaven after operating an “Indian Store” here in Oracle, AZ. While in Oracle, Mr Smith was the author/director of what was then known as the “Oracle Pageant of 1930”. Several years after the pageant he married the former Mrs. Mark Twain Clemans. Mrs. Clemans (Winifred Windeus) was the director of several “history pageants” held at the Casa Grande Ruins in the 1920’s during the tenure of Superintendent Pinkley. These were of course “faux” history events similiar to the Ramona pageants then held in California. My first cousin is a Clemans and his father was a nephew of Mark Twain Clemans…hence my distant connection. As a board member of the Oracle Historical Society, I have been looking into the story of Mr. Smith and the Oracle Pageant. I wonder, do you know of Mr. Smith or of his time in Pinehaven? Curiously, Byron Cummings, Frank Lockwood, and former Postmaster General Hitchcock attended the Oracle Pageant. I wonder if these connections later allowed for Mr. Smith to be designated Postmaster of Pinehaven?

Thanks for your terrific history of your family!

Oracle Historical Society

P.O. Box #10

Oracle, AZ 85623

Dear Mr. Medley, thank you for sharing these pieces of your interesting family history in your comment. My go-to source for the kind of information you are looking for is: Navajoland Trading Post Encyclopedia by Klara Kelley and Harris Francis, Window Rock, AZ, Navajo Nation Heritage and Historic Preservation Department, 2018, 532 pp. they mention Horace Smith’s involvement with the Pinehaven Trading Post and reference their sources, which might lead to additional information. If you would like to discuss any of this further, please don’t hesitate to let me know.