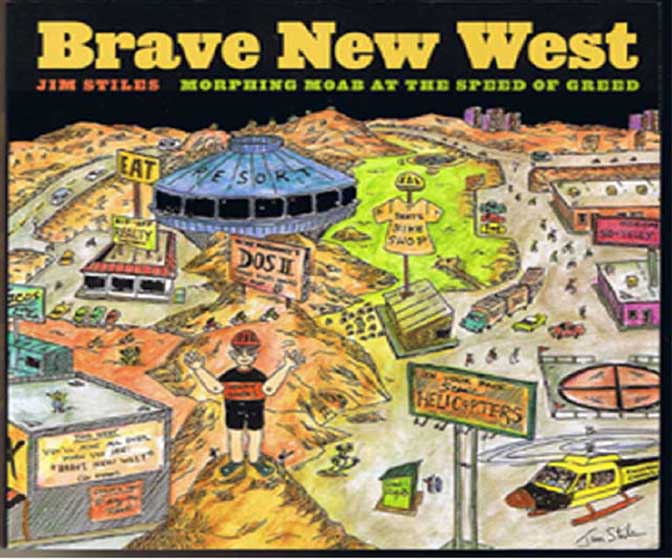

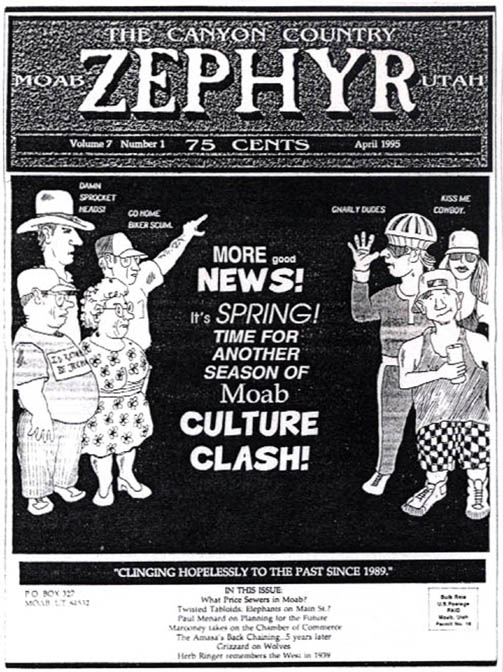

This is second of four planned excerpts from “Brave New West: Morphing Moab at the Speed of Greed.” In the spring of 2007, the University of Arizona Press published my one and only book. It vas a modest failure though it did sell out of the first printing. But UAP, for reasons I never completely understood, chose not to do a second printing and the book went out of print completely. I bought the last 100 copies and if demand doesn’t increase, I plan to be buried with them

It did occur to me that I now owned the rights to the book, and since still I feel like “dog-bottom pie” right now (a line I stole from Utah Phillips, I thought I might publish a few chapters from it. Newer Moabites will probably feel like they’re experiencing deja vu...There’s no telling where Moab’s destiny lies. But I can tell where and when it started. Trying to answer the question ‘Why” is easy—it’s in the subtitle of this book.

****

I was just a kid when I first heard the word wilderness, and being a good Methodist in those days, it came to me in its purest religious sense. While I have a knack for recalling trivia, I must admit my Biblical knowledge fails me on most counts. Still, stories of Moses leading his people into the Wilderness and Jesus spending 40 days in the Wilderness, being tempted by the Devil himself, sounded intriguing and mysterious, even to a five year old.

Just a year or so later, when we moved from our downtown apartment to one of the first suburbs of Louisville, Kentucky, I thought I’d found my own wilderness, right in my backyard. Glenmeade Road poked a solitary asphalt finger into what had been farm land for almost 200 years. Of course, the country had already been altered beyond recognition once by early white settlers in the late 18th Century. Kentucky was once dense with ancient hardwood forests and between these magnificent trees, endless “cane brakes” stretched for miles in all directions.

By the time we moved to Glenmeade, the virgin forests were all but gone but their descendants were still strong and tall and sported diameters of four feet or more. And cane brakes still clung to the edges of the forests and made perfect thickets through which to cut trails from one hideout to the next. Behind our house, a wheat field yawned across an eternity of space, bright and golden in the summer sun. And beyond the field, beyond the reach of any five year old, lay a forest as dark and impenetrable as any fortress Nature could construct. We called it “The Woods.”

No matter how old I live to be, no matter where I may travel on this planet, there will never be a place so full of mystery and excitement and adventure as was The Woods to my friends and me. The stories and legends that grew out of those trees still rekindle powerful feelings, even after all these years.

My friends and I knew The Woods was haunted. An old cemetery, consumed by grape vines and poison ivy, was a perfect breeding ground for spirits. We were sure that a remnant population of bears still resided deep within the forest. Never-before-seen bottomless swamps teemed with slime and dead bodies and poisonous snakes. Most frightening/exciting of all, reports of a hobo camp in The Woods, led by the notorious Big Lip Louie, sent chills up and down our spines when we discussed the possibilities.

This was wilderness. It had no designated boundaries and in our minds it went on forever. Wilderness was more than the sum of its parts. It was…unexplainable. It was a Mystery.

So it troubles me that the word wilderness has come to represent a political and bureaucratic designations as well. The W word rolls off the lips of some like a four-letter epithet.. Or that it has become an angrily chanted battle cry for those who both support and oppose wilderness. Or perhaps the greatest insult…when it becomes a legalistic game. A maneuver. Show me the passion and the mystery in an injunction.

Wilderness was supposed to inspire us. But somewhere we lost the poetry—or at least misplaced it. Wilderness wasn’t originally intended to create such contentiousness. More than boundary lines on a topographic map, wilderness is a state of mind, a feeling, an emotion. Wilderness is any place where we find silence and solitude, or adventure and surprise.

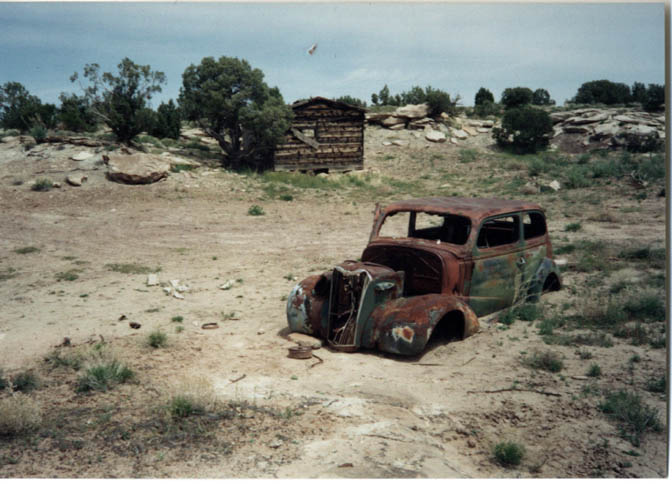

I drift back to my days as a kid and my journeys into The Woods and realize I can still find that same mystical connection to the land when I’m picking through the ruins of an old mining cabin in the Yellow Cat, north of Arches, and I look up through the darkness to the exposed rotting rafters and find myself eyeball to eyeball with a Great Horned Owl, who never blinks, and out-stares me, and backs me out the door with his fierce glare. Isn’t that a wilderness experience?

Or when I’m walking down the wash board road between the Bears Ears and suddenly the oak brush in front of me rustles, and a form begins to emerge from the leaves, and I’m stunned to see a beautiful, sleek mountain lion, whose muscles ripple in the sunlight as she walks silently in front of me, and stares deeply at me for just a moment, and then vanishes into the ravine below...isn’t that a wilderness experience? If I sit down to watch the sunset from the summit of Tillie’s Nipple, or Windy Point, or Nasty Flat, or UFO Hill, or a thousand other quiet forgotten places, and I sit there for hours and all I hear is the wind, the swallows, and the humming of my own brain, isn’t that wilderness?

Wilderness is anywhere we find things wild and free, and solitude that is long and unbroken. All these places deserve our respect and our reverence and our concern, or they will not survive. Not all the places I’ve mentioned (and most of the names I invented) are considered ‘wilderness’ by anyone. They don’t meet the official criteria. But I worry that wilderness, in a congressionally-designated way, will somehow suggest to the world that the remainder of the land is unworthy of any respect at all.

All land is sacred, and we need to remember that, especially as the beauty of the land itself becomes the ‘product’ that fuels the every-growing and powerful tourism industry. It’s not enough to be a ‘recreationist.’ People come here to play, but this is not a playground. The day we treat all of these lands with the reverence they deserve is the day we won’t need wilderness designation at all.

Sad to say, that time has not arrived. In fact, not that long ago, none of this rancor and debate existed because none of the land in question was wanted by anyone. Barely a century ago, the Deseret News in Salt Lake City described the lands of southeast Utah as “one vast ‘contiguity of waste’ and measurably valueless, excepting for nomadic purposes, hunting grounds for Indians, and to hold the world together.”

Ranchers in the 19th Century discovered the tall grasses in the La Sal Mountains, ran their herds there and on the tablelands and deserts below, and by the early 20th Century had left much of the rangeland burnt to a cinder. But ranchers, and later miners when the uranium boom came to Utah, would have laughed (or shot) an environmentalist right out of the country. Land was to be used, not looked at. Certainly not “preserved.” Land could only be appreciated if it could be assigned a dollar value. That was the key for the environmental community.

Wilderness possessed intangible values that transcended all that—-or was supposed to. That is why we needed wilderness designation and why the Wilderness Act was passed by Congress in 1964. Then and now, we need it for the right reasons. For all the right reasons. In the 21st Century, those reasons are more complicated than even the most dedicated professional environmentalists are often willing to consider.

1990s…Times have changed. Twenty years ago, no intrusion on the red desert of southeast Utah seemed as ugly or intrusive to me as a seismic truck and a goddamn cow. (AUTHOR NOTE: And in 2023 I feel downright foolish. JS)

During my seasonal ranger days at Arches National Park I watched helplessly and grumbled futilely as monstrous seismic vehicles, loaded with tons of high tech equipment, crept ponderously but surely across the valleys and mesas adjacent to the park boundary. Seismic crews pounded stakes and the neon ribbons to mark their planned trajectory. and eventually crushed everything in their path; the result, years and decades later, there and elsewhere, is a patchwork of intersecting “roads” that, when viewed from the air, begin nowhere and end nowhere. Future civilizations may wonder just what in the hell we were doing. Perhaps they’ll think they were alien landing strips. Or perhaps Eric Von Daniken was wrong about mysteries like the Nacza Plain. All those confusing lines were simply the handy work of Inca seismic trucks during the planet’s last industrial incarnation.

Cows wandered frequently into the Arches; they fouled the water in Courthouse Wash and, for reasons I could never explain, faithfully and regularly made their way up the park road (always on the right side) to Balanced Rock, where they seemed to congregate near the viewpoint until local rancher Don Holyoak came up with his truck and removed them. It was the park’s responsibility to fence the cows out but never-ending budget constraints made that task nearly impossible. And so, for years, the cattle shuffled in and shuffled out. Some may have had Golden Age Passports.

Environmentalists in Southeast Utah, as elsewhere in the Intermountain West, viewed the battle to save its dwindling wilderness lands in very black and white terms. And with good reason. Twenty years ago, the Rural West was still a vast, mostly unpopulated expanse of deserts and mountains and prairies, dotted with tiny communities that had changed little in a century, which depended mostly on the extractive industries for survival and which might, at best, get a small boost from tourism during the summer. Even in tourist vortexes like Jackson, Wyoming, gateway to Grand Teton and Yellowstone Parks, the tourist season barely lasted three months. They called the long off-season in Jackson the “cocktail hour.” It was that quiet.

Tourists, as we’ve already determined, could be a terrible annoyance, but their impacts were temporary and their visits were limited. And while their numbers seemed overwhelming at the time, they did have the decency to leave. Even in desert recreation meccas like Moab, the crowds had thinned to a trickle by October and the canyon country had time to recover. The lands didn’t need “management” for tourist impacts; they simply needed to be left alone.

And so environmentalists devoted their time and energy and resources to fight the threats to wildlands they thought were most persistent and enduring–mining, timber, and cattle. In 1983, the Reagan Administration’s Secretary of the Interior, James Watt, came to represent everything environmentalists feared from a government, in partnership with Big Business, that saw land as simply a commodity to exploit for its natural resources.

We protested the accelerated energy exploration programs of the 80s, the extensive chaining of thousands of acres of pinyon-juniper forests to expand rangelands for ranchers, the destruction of forest lands in the mountains that saw the construction of new roads and the loss of wildlife habitat. We thought that if these lands could be spared further degradation by these huge industries, the West would simply be left alone.

Our assumptions were tragically wrong.

In the late 1980s, the conflict between the Rural and Urban West came more clearly into focus. Here in Utah, the Southern Utah Wilderness Alliance changed its strategy and began to abandon its local emphasis. Wilderness, SUWA argued, was not a local issue. The BLM wilderness lands in Utah were owned by all Americans, and consequently they deserved a greater voice in determining how those lands should be used. SUWA’s membership skyrocketed, jumping from 2000 in 1985, to 20,000 by the mid-1990s. It argued that New Yorkers and Californians and Floridians had just as much of a stake in the future of Utah wilderness as a fourth generation rancher in Escalante. Never before had the argument been so polarized. It would get so much worse.

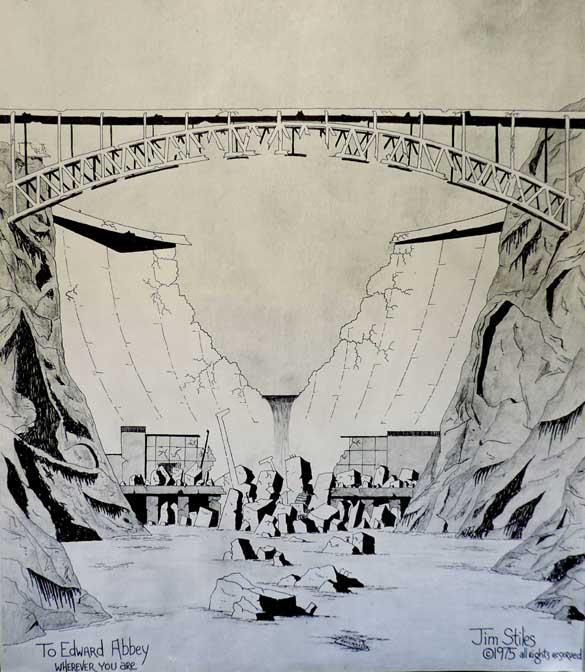

In the 1980s, the idea of wilderness needed no justification for most of us–it was simply the right thing to do. We believed that there should be places on this planet spared from the Hand of Man. Wilderness should be saved for the rocks and the trees and the animals that inhabited those lands. If wilderness offered a recreational benefit or an economic advantage, or even spiritual enrichment, those opportunities were secondary achievements. And beyond the legal designation of wilderness areas, environmentalists strove to raise the level of sensitivity to all lands.

Rural Westerners recoiled at the idea of wilderness designation, as non-motorized recreational tourism increased and small Western towns felt the economic impact of those increases. Wilderness proposals were met with anger and fear; if large tracts of land were shut down to any “mechanized vehicle” as the Wilderness Act mandated, they believed the collapse of the Rural West was inevitable. And it wasn’t just its job market–the economics of the West was always a primary concern, but there was more to it than just the shutdown of public lands to extractive industries like oil and gas. They feared the loss of a lifestyle that not many urban Americans can understand, much less appreciate. The Rural Westerners may not have appreciated the dynamics and interplay of cryptobiotic soil communities or the sexual habits of a Blackfooted ferret, but they understood another component of wilderness far better than most members of the Sierra Club. Rural Westerners understood Solitude.

City dwellers can still not fathom the isolation and remoteness of most Rural Western towns or comprehend just what the people who reside in these communities do. For the better part of a century Rural Westerners basked in the emptiness and solitude of the American West and loved it. Now suddenly, the onslaught of forces dedicated to “saving” the very places Rural Westerners had assumed would always remain empty and mostly untouched, seemed impossible.

By 1990, the rhetoric had been ramped up on both sides. “They want to lock it up for the elite few!” was the battle cry of most Rural Utahns at the turn of the decade. That spring, anti-wilderness advocates publicly presented a study paid for by the Utah Association of Counties; it attempted to prove that wilderness designation would have dire effects on the state’s rural economy. The study’s author, Dr. George Leaming, concluded in his report that designating 5.1 million acres of BLM lands as wilderness in Utah would cost its citizens $13.2 billion over the next 25 years. Leaming’s estimates depended on two assumptions: What economic activities would have happened in a non-wilderness area? and how would these activities be reduced or eliminated by wilderness designation? His assumptions were extraordinary; the Leaming Report was based on the notion that without wilderness, 80% of all speculative minerals would be recovered and sold by 2015, and that with wilderness designation, all grazing, all mining, and all recreational visitations would cease. Completely.

The Leaming Report was easy to dismiss and other studies clearly showed that the numbers were extravagant. Three years earlier, Republican Governor Norm Bangerter created a Resource Development Coordinating Committee to consider the impacts of wilderness and could find no sign of economic disaster waiting in the wings. The report noted, “It is unlikely that exploration or development would occur in most wilderness study areas even without wilderness designation.”

But wilderness proponents were compelled to take the argument a step further. Supporting wilderness offered certain economic advantages that environmentalists believed should not be overlooked. Enviros pointed to a 1987 study by the University of Idaho that compared economic growth in rural western counties that contain federal wilderness, versus the growth of non-wilderness counties. The study concluded, “Counties which contain or are adjacent to federally designated wilderness are among the fastest growing in the United States.”

Or as Lance Christie wrote in a 1991 Zephyr article titled, “Wilderness Economics: Boom and Bust Baloney,” in behalf of the Utah Chapter of the Sierra Club: “Studies done on the economic impacts of wilderness on local economies consistently support the idea that designated wilderness in an area acts like an advertisement that says: ‘Here is a treasure house of environmental amenities! And, they’ll be here tomorrow because some treasure-hunter with a bulldozer can’t come and tear them up.’ This advertising attracts people economists call ‘amenity migrants,’ causing twice the economic growth in rural areas with designated wilderness than in areas without wilderness.”

Christie concluded, “The migrants responsible for this growth are younger, highly educated and move in to enjoy environmental amenities rather than because of economic opportunities…Once there, these energetic and educated people develop their own economic opportunities.”

The Southern Utah Wilderness Alliance weighed in on the issue. It asked the question: “What is the economic impact of wilderness designation?” and had a ready answer. “Rural Utah counties that have booming economies, such as Grand and Washington, are growing because the public land, open space, and scenery provide the setting for a healthy tourist industry with an influx of people who want to live in such a spectacular setting. The future of Utah’s economy lies in preservation of its wildlands and quality of life, as opposed to promotion of an economy based on the extractive industries.”

(PHOTO by SUWA)

The economic message from almost all environmental groups was bewildering and a bit duplicitous. While environmentalists attempted to suggest that the economics of wilderness would benefit Rural Utah, their wilderness economics strategy would never augment or benefit the rural citizens who already lived there. Ranchers and oil field workers didn’t have the money or the skills or the inclination to invest in tourist-based businesses. What was being proposed and embraced by the environmental community was a new economy that would simply destroy the old lifestyle of the Rural West and replace it with a new one. Where would the Rural Westerners go? Perhaps they could get jobs at McDonald’s or the Motel 6–environmentalists were vague on the fine points.

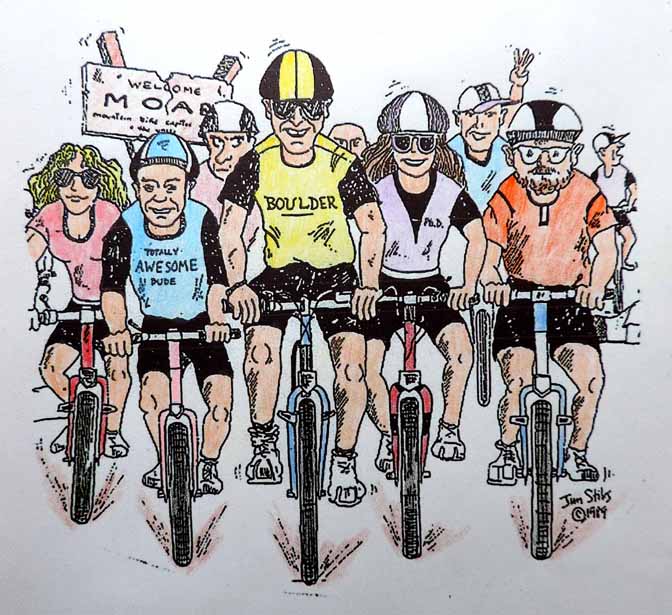

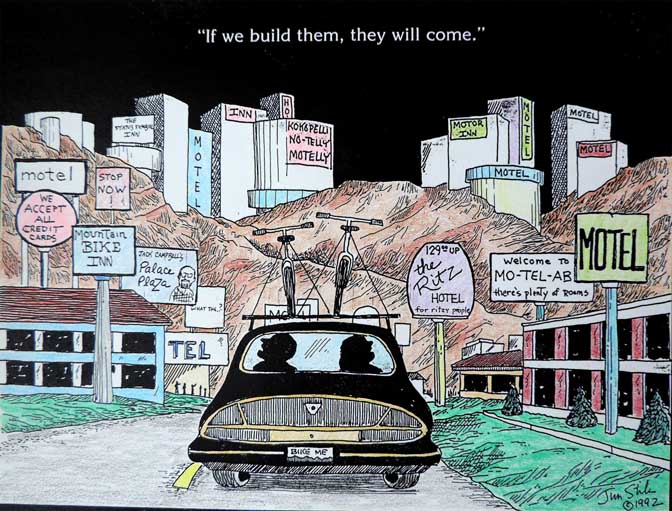

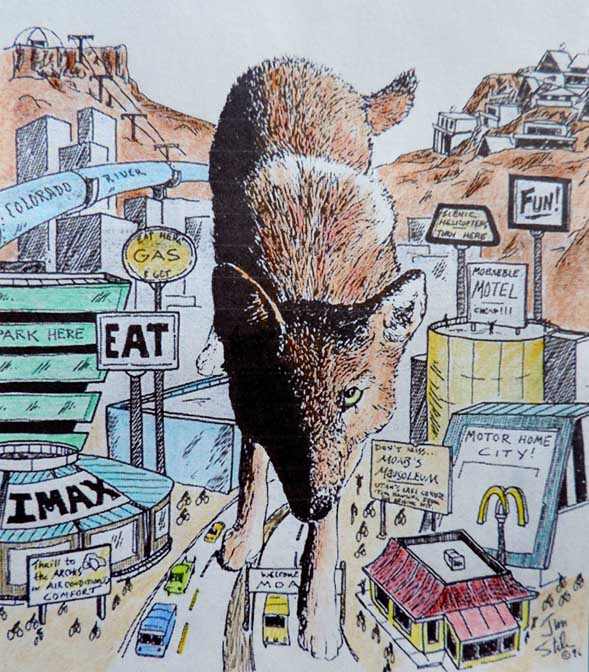

And what of these “booming economies” in places like Moab? Did the explosive growth of “amenity migrants” carry their own environmental risks? By the early 1990s, places like Moab had indeed exploded. Visitation in nearby national parks doubled in five years. Adjacent BLM lands were hardest hit. Visitor use jumped from about 130,000 in 1985 to over a million in a little more than a decade. Many of us kept waiting for the same kind of resistance from “our side” that had met ranchers and seismic trucks but the professional environmental community said little of these new kinds of staggering impacts and the exploitation that brought them.

But Lily Mae Noorlander did. Ms. Noorlander grew up in Moab, lived through good times and bad, reveled in the quiet days when Moab was a sleepy orchard town, watched Moab come alive in the 50s, only to see it go bust in the 60s–she had seen it all. But Lily Mae had never seen anything like this. To her, recreational exploitation was the Mother of all Obscenities.

In a letter to the Deseret News in 1994, Ms. Noorlander wrote:

“Long-forgotten ranches, abandoned decades ago, are now front page fare in the full-color marketing pieces of this lucrative industry…Some of the direct consequences of their promotional activities, aside from generating profit from calendars, hiking exposes and membership dues include: more foot trails, bike trails, garbage, human waste, instructional signs, regulations, law enforcement patrols, costs to local government for crowd control, and a general loss of peace and serenity to the plaid clad, waffle stomper crowd.

“The spirit of wilderness, “has already been stolen by those who profess to be its savior, but who have, in fact, trampled the life out of its essential serenity and solitude in an orgy of self-indulgence.”

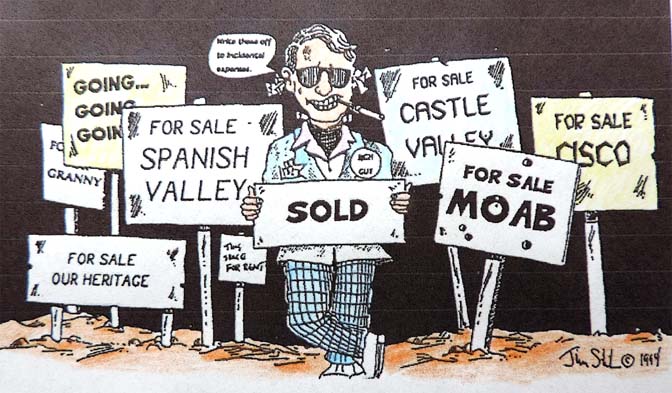

A few months later, as if to confirm Ms. Noorlander’s greatest fears and suspicions, a letter was published in the Salt Lake Tribune and titled, “There’s Money in Wilderness.” The author was Randall Tolpinrud, president of Groupwest Properties Corporation in Salt Lake City. He wrote, in part:

“As a real-estate developer and homebuilder in Utah, I have a very strong interest in maintaining the long-term economic foundation of this region…Because of this conviction, I am concerned over the wilderness proposal suggested by our congressional delegation.

“I support the Utah Wilderness Coalition’s proposal for 5.7 million acres (in 2006, the proposal is near 10 million) of wilderness primarily because the long-term economic potential which wilderness designation will provide this state.

“The West is changing dramatically. Lands from Montana to New Mexico are rapidly being developed by people like myself in response to growing migration and population…We must look years and decades ahead. Wilderness designation will grow to represent a powerful economic opportunity as the West’s open spaces shrivel from development. Utah, with its unique beauty and abundant national parks, could be positioned to reap significant economic rewards from masses of people seeking solitude in a wilderness experience from their fast-paced lives.”

It was an extraordinary letter. Mr Tolpinrud was saying in effect, “Look…people like me are going to develop most of the West’s open space. If you can save what we promoters can’t get our hands on, we can make money from that as well.” There was something contradictory about his image of “masses of people seeking solace in wilderness.” How long would it take and how big would the ‘masses’ have to become before the purity of those wildlands was so degraded, they could no longer be called wilderness?

And that is the issue here.

I expected some sort of response from at least one of the Utah environmental organizations, but there were none forthcoming. The silence was deafening. In their quest to run up their membership rolls, and especially as the cost of lobbying Congress grew ever more expensive, groups like SUWA were hard-pressed to refuse the support of anyone, no matter how tainted their reasons for supporting wilderness were. What mattered was money. And lots of it. It wasn’t a matter of environmentalists gone greedy or corrupt. They simply saw no other way to push their wilderness agenda than to play the high-dollar game. Just like the other guys. The danger was in becoming just like the other guys.

Meanwhile, the impacts from millions of those well-meaning “amenity clients” became more obvious with each passing season. Resource damage from hundreds of thousands of bicyclists, as far as 30 and 40 miles from Moab was clearly changing the landscape of Grand County. And it wasn’t just the bikes. It was the vehicles that brought the bikes and bikers–it became a bit embarrassing to praise the non-polluting aspects of non-motorized recreation when most bikers drive their SUVs hundreds of miles so they can pedal for ten.

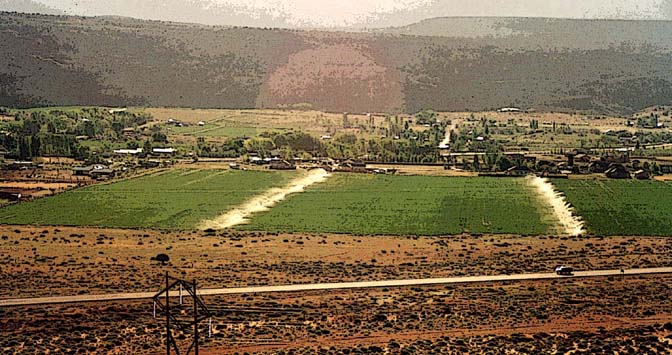

There were cultural and social impacts as well. In Moab and Grand County, the housing boom that began in the 90s continued a decade later at full steam and with no sign of a pause. Most of the agricultural lands in the valley began to disappear literally overnight. The vast numbers of people coming to build in the canyon country posed a greater threat to the surrounding wildlands than anything else imaginable.

Habitat encroachment and a permanent human presence drive wildlife to the edge. How many times have we heard the same story? An affluent urban family wants to get closer to Nature and builds its home in the midst of it. They’re thrilled and excited to see the deer browse from their picture window, but when a coyote carries off Fluffy, the family poodle, attitudes change rapidly. Two years ago, a cougar attacked and killed two bicyclists pedaling through an area that had been too isolated to enter until recreational trails were built and the teeming masses from nearby Los Angeles sought refuge in it. The cougar was promptly shot by wildlife officers and not one environmental group objected, proving that environmentalists will defend the rights of wild animals until they start eating their members.

Environmental organizations in Utah stayed silent. For example, SUWA contributed regularly to each issue of The Zephyr for more than ten years. In that decade, SUWA wrote tens of thousands of words about a variety of concerns and impacts affecting the canyon country. By category, they wrote scores of articles about cattle, about mining and oil and gas exploration and about ATVs. But stories devoted to non-motorized impacts or the ever-growing amenities economy numbered just two.

Either they refused to acknowledge or simply hadn’t noticed that the Rural West was changing, in ways they themselves had predicted. And wanted.

Rural Westerners, alarmed at the sudden influx of urban immigrants, reacted angrily and fearfully. They had enjoyed, for better or worse, carte blanche on public lands for a century. As one old cowboy said, “I could feel the saddle turning under me…everything was changing.” There was an irony here. Many of the third and fourth generation ranch families who had lived in these small western towns were the descendants of the original settlers. They had come west in the last half of the 19th Century and had played a decisive role in driving the buffalo to near-extinction and had all but obliterated Native American culture. White settlers in 1876 could not find a single redeeming aspect of Native American life. As General Philip Sheridan once said, “We took away their country, broke up their mode of living, their habits of life, introduced disease and decay. And it was for this and against this that they make war, Could anyone expect less?”

But Sheridan also said, “The only good Indians I saw were dead.” It was always that kind of contradictory rhetoric that confused and bewildered the Indians, even as they were being slaughtered by the thousands.

Now in the 21st Century, the great-great grandchildren of the white people who showed so little tolerance for a culture they didn’t understand, and thus feared, face a certain kind of extinction themselves, certainly not as brutal as the “justice” their ancestors meted out against the Indians, but in terms of maintaining a way of life, just as terminal.

Whether they somehow deserve to pay a price for the sins of their forefathers has nothing to do with their threatened existence. In fact, the reasons for their endangered status are not that different from the Native Americans’ plight a century ago. Rural Westerners are simply in the way. They impede the march of progress. The Brave New West wants their land, just as their ancestors wanted the Indians’.

Opportunities for reconciliation and resolution are just as rare now as then too. Rural Westerners have responded passionately but often irrationally. New Westerners aren’t interested in a dialogue at all. Do Old Westerners get so frustrated by the silence that they become destructive? Or is it the irrational violence of Old Westerners that keeps New Westerners from sitting at the same table in the first place?

For instance, anti-wilderness individuals have gone so far as to deliberately enter proposed wilderness study areas designated by the BLM, and into areas proposed for wilderness but without legal protection, for the sole purpose of doing enough environmental damage to disqualify it as wilderness land completely. We’ve all seen the destruction that unrestricted ATV use can cause in the fragile desert landscape. For many people, including a majority of ATV users, the wanton destruction is inexcusable. It creates stereotypes that only deepen the chasm between the two sides. Yet responsible motorized recreationists are loathe to criticize their peers, lest they be accused of acting like their adversaries.

And anti-wilderness forces have clung to a century old law called RS 2477 which allegedly gave the states legal right-of-ways across public lands. Utah has claimed thousands of miles of RS 2477 access as a way of stopping wilderness designation. That battle is still being fought in the courts.

Environmentalists display their own stubborn streaks—not only do they refuse to discuss the future of public lands with their opponents, they keep dramatically raising the stakes. In the early 90s, “5.4—KEEP IT WILD” was the battle cry of the wilderness movement in Utah. It referred to the 5.4 million acres that enviros believed existed on BLM lands in Utah. Utah politicians thought a million was about right. The BLM’s studies came in at 3.2 million acres. SUWA and the UWC (Utah Wilderness Coalition) upped that number to 5.7 million and it stayed there for a long time. It seemed as if the battle lines were drawn and this is where the fight would be waged.

Then in 1999 the UWC conducted a new citizens inventory. Hundreds of volunteers were sent out to examine these BLM lands closeup. The numbers they came up with were stunning. Now they’d found 8.3 million acres. Then the number jumped to 8.8. Then 9.1. Then 10. Even I was puzzled by the increases. Environmentalists have been saying for two decades that wildlands in Utah were under perpetual assault and were shrinking daily at an alarming rate. How then could we have overlooked five million acres of wilderness that had apparently been there all along?

At the heart of any debate about wilderness is roads. Roads, or the lack of them, is what defines wilderness. The Wilderness Act criteria requires that it be a roadless area no less than 5000 acres in size. For almost as long as I’ve been familiar with wilderness designation, trying to determine when a route is a road has always been a subjective argument. Ultimately it came down to usage; if a jeep track could be proven to carry fairly regular vehicular traffic, it was a road. If an old two-track, left over from the uranium days was barely used at all, environmentalists thought they could include such a remnant in proposed wilderness. But a re-reading of the Federal Land Protection Management Act (FLPMA) few years ago, changed some preconceptions and even many ardent environmentalists still don’t realize it.

According to SUWA’s web site, “The word ‘roadless’ refers to the absence of roads that have been improved and maintained by mechanical means to insure relatively regular and continuous use. A way maintained solely by the passage of vehicles does not constitute a road. The key word in this definition is ‘maintained.’”

But SUWA added, “We will sometimes exclude a vehicle route from our wilderness proposal if we feel it looks like a “road” to a hypothetical typical American, or if it serves some important purpose…such as unmaintained “two track” jeep roads that receive moderate to high recreational use.”

If they mean what they say, then SUWA and other members of the Utah Wilderness Coalition believe they have the legal right to demand the closure of every jeep road in Utah, unless it receives heavy use. There’s no other way to read their own interpretation of the law. The fact that they don’t, in their minds, is a measure of their own perceived generosity.

(SUWA, in fact, insists that the “roads” definition has nothing to do with their expanded wilderness proposal and claims that they merely went back and inventoried land previously unexamined for wilderness characteristics. But that raises the question: How did all that unprotected public land escape unscathed after 20 years of anonymity?)

Not long ago, dozens of Moab businesses attached their names to a full page ad in The Salt Lake Tribune. It was paid for by SUWA and its aim was to call attention to the damage being caused to public lands by excessive and abusive ATV recreation. No one but the blind and the stupid can argue that the damage was extraordinary. Bill Burke, a professional tour operator from Colorado and a long-time advocate of environmentally responsible four wheeling sent an angry email to his jeeper peers after the 2005 Moab Jeep Safari. “What I saw last week really sickened me,” Burke wrote, and makes me wonder why I continue to be aligned with this sport…” Burke was “afraid that the actions of the uncaring, indolent, boorish imbeciles will drive the general public and land managing agencies to start pushing for road closures and more government interference.”

For the “imbeciles,” there’s no excuse for their bad behavior.

But one day, talking with one of those SUWA sponsor/business owners, he mentioned the angry emails he’d received from ATV enthusiasts and their boycott threats.

“I just don’t understand why these ATVers aren’t content with the roads they already have. There’s hundreds of old jeep roads left over from the uranium prospectors. How much more do they want?”

Even though he was a business member of SUWA and had attached his business name to the SUWA advertisement, he was unaware of its relatively recent revelation on the definition of roads. Nor did he know that the UWC’s wilderness proposal had almost doubled since 1994. Like so many other urban enviros, he was oblivious to the facts. And yet if there was any room for dialogue between the two entrenched and warring factions, no one took advantage of it. Road crews from rural counties defiantly bladed and bulldozed some of the contested roads, as if to say, “You didn’t think it was a road before? Well it sure as hell is a road NOW!”

Jeepers and ATV users went out of their way to create even more damage. It reaffirmed in environmentalists’ minds just how ignorant and insensitive Rural Westerners could be when it came to protecting natural resources on public lands. Rural Westerners were even more convinced that environmentalists would use any ploy, run any legal maneuver to keep them from the land they’d used for a hundred years. Old timers tolerated bad behavior from their own side, if it meant maintaining a united front against enviros.

Environmentalists defended and even supported the economic exploitation of wilderness lands that were sure to eventually cause impacts of their own, and looked for legal loopholes to expand wilderness designation, convinced that legal restrictions were the only way to protect public lands.

Lost in the melee was wilderness itself.

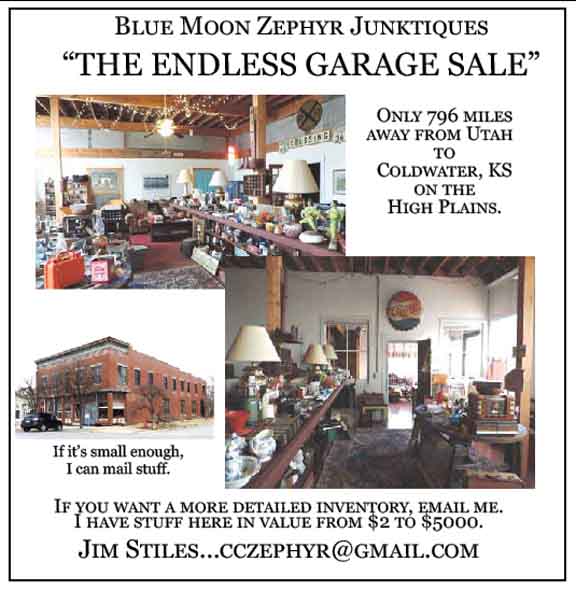

Jim Stiles is the publisher and editor of The Zephyr. Still “hopelessly clinging to the past since 1989.” Though he spent 40 years living in the canyon country of southeast Utah, Stiles now resides on the Great Plains, in a tiny farm and ranch community, Coldwater, Kansas, where there are no tourists.

He can be reached via facebook or by email: cczephyr@gmail.com

TO COMMENT ON THIS STORY, PLEASE SCROLL TO THE BOTTOM OF THIS PAGE.

https://www.facebook.com/FansoftheCanyonCountryZephyr/

And I encourage you to “like” & “share” individual posts.

Why they can’t just leave the site alone is beyond me,

but that’s what Facebook likes to do.

ALSO NOTE: I post old photographs and stories from our 25 year old archives every day. Pictures from Herb Ringer, Edna Fridley, Charles Kreischer.. even a few old photos from my Dad. So if you want to stay caught up on our historic photo collections,

be sure to “follow” us on Facebook…Thanks…Jim

https://www.facebook.com/FansoftheCanyonCountryZephyr/

https://www.facebook.com/profile.php?id=100086441524150

And check out this post about Mazza & our friend Ali Sabbah,

and the greatest of culinary honors:

https://www.saltlakemagazine.com/mazza-salt-lake-city/

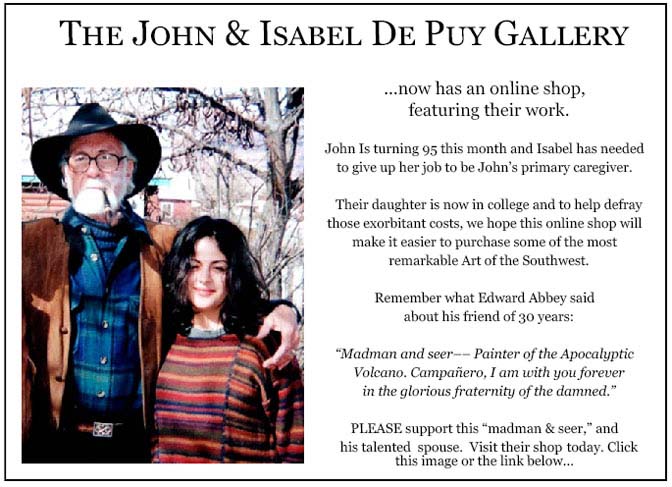

More than six years ago, The Zephyr, me & four other individuals were sued for defamation by the former Moab City Manager. Faced with mounting legal bills, my dear friends John and Isabel De Puy donated one of John’s paintings to be auctioned.

ALL the proceeds went to our defense.

Thanks to them, our bills were almost completely covered.

Now I’d like to return the favor. Check out the link below and their online shop… JS

https://www.depuygallery.com/shop.html

And once more, now that you’ve read the latest Zephyr Extra and waded through the ads, please take a minute to comment. Thanks for your support…. Jim Stiles

BRAVE NEW WEST, one of my favorite books on the Moab area! Really liked the old notice about Steve Allen and the “Canyoneering Chronicles.” I have known Steve for many years and have had the pleasure of hiking with him many times!

I can see the spine of my copy of Brave New West from where I sit. You called it. Damn shame…

High Country News is the problem.

Church Wells still scares off the plastic people, but they’re getting closer. When Kali real estate goes belly up, that should fix most of them.

Oh yeh–but you’re preaching to the choir. Even though your first printing “sold out” (after you bought the last 100 copies yourself), it doesn’t surprise me that the publisher passed on a second printing. Such wonderful nihilism, regardless of how true a reflection of reality (as yours was and is) will never generate a profit. People want to be Pollyanna’d and petted like kittens. High Country News stopped publishing my essays when I became “too” cynical for those who needed Pollyanna. But reality breeds cynicism, how can it not? What’s the answer? The apocalypse? Lots of questions on these subjects, but few answers. Kick back another cold one, Jim!

Honestly most of the “choir” doesn’t get either. These posts aren’t intended to ignite a wider readership. It is just to remind readers that as new Moabites discover the same problem, this has been going on for years. It’s been over two decades since I started writing these kinds of warnings about runaway growth of tourism and the threat of making it the ONLY economy that could “save Moab. “

I enjoy these posts a great deal–they remind me of what I can be grateful for having once known and the older historical stuff illuminates the west that existed in my childhood, before I ever had a chance to know it personally. I like knowing how things get to be the way they are and, in the case of these Z posts, how they once were. Thanks Jim!

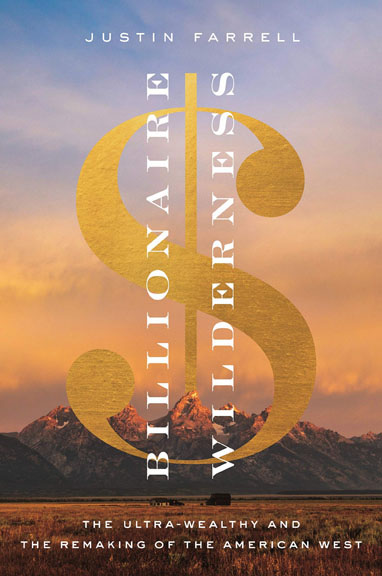

No doubt the deafening silence from the “environmental” side won’t even now be broken. Their embarrassment is complete. It’s history now and historians wanting to understand what happened need look no further than The Greening of Wilderne$$ , parts 1 and 2, along with Justin Farrell’s Billionaire Wilderness about a decade later.

Unfortunately, the 1964 Wilderness Act, a product of the politics of the United States of America, didn’t quite live up to the idealism of the 1960s. Look closely and you’ll find text protecting the rights of guide businesses to ferry paying customers in and out of the “wilderness”. Idealism was never gonna be any match for money making, the latter being too much a part of both sides’ DNA.

Thanks for mentioning Justin Farrell’s book, “Billionaire Wilderness.” The Zephyr ran an excerpt from his book in October. Here is a link to it:

https://www.canyoncountryzephyr.com/2020/09/30/an-excerpt-from-billionaire-wilderness-the-ultra-wealthy-the-remaking-of-the-american-west-by-justin-farrell/

I also wrote a brief introduction in my “Take it or Leave it” from that issue…

https://www.canyoncountryzephyr.com/2020/09/30/take-it-or-leave-it-a-few-words-about-justin-farrell-and-billionaire-wilderness-by-jim-stiles/

At the bottom of this story, but above this comment, is a link to Justin’s book on Amazon…check it out…just scroll UP

You got that RIGHT! Moab is no longer a small town ~ where you know your neighbors and everyone at the grocery store! NOW it is so packed with visitors and short-time renters and the occasional person that comes and uses their vacation home. It is a sad place where the majority does not care what happens to Moab as long as they can get their choice of meat, drinks and excitement! After-all this is not their home ~ this is the place where they can come and be wild, have fun and not have to answer for any of their transgressions.

Wow, Jim, you are an incredibly talented writer, journalist, and observer. This chapter covers so much ground, it’s hard to digest. I, too, watched Moab morph from the faded uranium mecca with an incipient tourism base in 1970 when I signed papers in the Uranium Building downtown for my first Park Service job to the overburden of development and congestion it is today. It’s now a place I stay away from mostly. While unique, Moab isn’t alone. I visited Telluride and Springdale also in those early years, and then revisited them in the 2000s, and simply couldn’t recognize them. It is indeed the poster for your Brave New West.

As for wilderness, I like your description of the sense of wilderness from your Kentucky boyhood experience. It can be as much within as without. But it doesn’t preserve itself. Because the forces of change are irrepressible, the physical wilderness does need a bureaucracy and a boundary definition to retain the qualities and experiences that we who value it can experience. It’s a different wilderness that the one my father and uncle knew, but it is still a refuge, tainted as it may be sometimes. Was it Ed Abbey who said something like “Wilderness needs no defense, only defenders”?

I get very cynical sometimes when I see the constant impact on our West (and everywhere for that matter) by the use and display of profligate wealth. I see it in my home city of Bend, Oregon, and I see it daily during my summer Park Service jobs in Utah. So I treasure those dirt road pictures you share from the 50s and 60s, which I had the privilege of experiencing myself briefly as I came of age. But these are snapshots in time. Can this continue? Is it sustainable? Honestly, I suspect a century or two from now, the story may look very different.

Indeed it was Ed Abbey who said “the idea of wilderness needs no defense, only more defenders” and if you look hard on this site you’ll see that Jim has pointedly criticized Ed for that statement (here and here, for example.) Ed’s statement and also yours that “physical wilderness does need a bureaucracy” really misses the main point that this publication has been making for more than three decades, ie, that formal “protection” of land actually worsens honest environmental values. Official “protection” instantly means “promotion” and the game is over at that point.

I’ve always favored the perspective of Abbey’s good friend Charles Bowden, who took a dim view of Abbey’s belief that environmental writing could change the world. Bowden understood “civilized” humanity for the destructive force that it actually is and no doubt, like me, would be pleased seeing that human fertility rates in the developed world are now below replacement level. Whether by choice or more likely due to economic necessity, there’s our only “hope”.

Indeed it was Ed Abbey who said “the idea of wilderness needs no defense, only more defenders” and if you look hard on this site you’ll see that Jim has pointedly criticized Ed for that statement (two example articles listed below.) Ed’s statement and also yours that “physical wilderness does need a bureaucracy” both miss the essential point made here over and over: that formal “protection” of land actually worsens honest environmental values. Official “protection” instantly means “promotion”, resulting in a net loss for the land health, even when compared to mining impacts.

I’ve always favored the perspective of Abbey’s good friend Charles Bowden, who took a dim view of Abbey’s belief that environmental writing could change the world. Bowden understood “civilized” humanity for the destructive force that it actually is and no doubt, like me, would be pleased seeing that human fertility rates in the developed world are now below replacement level. Whether by choice or more likely due to economic necessity, there’s our only “hope”.

“Take it or Leave it: ‘New West Blues’ Revisited, 30 Years Later… by Jim Stiles” – May 31, 2021

“EDWARD ABBEY: 34 YEARS LATER in a BRAVE NEW WORLD—Jim Stiles (ZX#53)” – March 12, 2023

We cynics should create our own organization. I once promoted the idea of a group called MAHBU—Mormons and Heathens for a Better Utah. A feeble attempt to find kindred spirits, who may not agree with me all the time, but who would be willing to listen. Oddly, or maybe predictably, the only groups interested were my LDS friends…Now years later, even the concept of seeking friendly and constructive debate seems like a fantasy….I’ve lived too long.

I got your book when it first came out and was on board back then. That said, I never would’ve thought things would get to where we are today. Last time I was in Moab, I was waiting my turn at a 4 way stop while a congo line of Razors about 18 strong just kept rolling through, none waiting their turn.

A brilliant and complete picture and analysis of what has happened and why in canyon country. Unfortunately canyon country is a microcosm of what is happening all over the intermountain west as well as rural areas all over America.

Sadly it can’t be stopped as the urban/suburban environment becomes less habitable for many reasons and people who can afford to will continue to flee. I am not optimistic about the future for my great grand children.

As for being a cynic, a person who thinks all people are motivated by selfishness, I am not one. Unfortunately in this current American state of record income disparity, it’s evident that some people definitely are. I suspect that readers of the Z are not in that category.

In the future, Stiles will be read and regarded as a prophet. Those of us who have been reading the Z since the early days and have watched what’s happened to Moab and environs already know that he is.

Long live the Z and Stiles!

Are you drinking ardent spirits again Joseph? “Prophet?” No way. But I’m at least confident that, in the future, no one can accuse me of keeping the Zephyr going for the “PROFIT” in it.

A very poignant article, and there’s a lot I agree with even though I suspect we would normally be on opposite sides of the wilderness issue. As a Jeeper and motorized access advocate, I greatly appreciated your acknowledgement that recent wilderness proposals in Utah have relied on stretching the definition of “roadless” beyond all recognition, such that what SUWA claims are wilderness quality lands are actually covered with roads, including many of the most popular Jeep trails in southern Utah. SUWA’s current wilderness proposals are not about protecting existing roadless areas, but about creating new roadless areas by closing vitally important roads that both locals and visitors depend on to access public lands.

I also appreciate your acknowledgement that one can have “wilderness experiences” outside of legally designated wilderness. To me, wilderness experience is about solitude and self-reliance. While I have had many of these experiences hiking and backpacking in designated wilderness areas, I have the same kinds of experiences solo offroading, driving my Jeep deep into the backcountry on faded tracks that are nearly forgotten, where I barely see any other vehicles all day and where if something goes wrong, it’s up to me to self-rescue and fix it. Contrary to what many people think, such experiences can still be found even near Moab, as I discovered a couple years ago when I spent four days exploring obscure roads in the Labyrinth Rims / Gemini Bridges area that the BLM is proposing to close in the new travel plan in order to placate SUWA’s demands for more wilderness.

I find it sad that so many people in the environmental community have bought into the notion that only hikers deserve to have wilderness experiences – to experience solitude and self-reliance when exploring remote backcountry areas. By defining wilderness solely in terms of who is excluded, setting the stage for endless zero sum political battles, wilderness itself has indeed been lost in the melee.

Hi Jim I haven’t started your book yet but I can see it will be up there with Cadillac Desert showing the folly of man and the greed of progress. I don’t think anything can be done unfortunately as money will always win.Thank you for your labor of love here.

Thanks Shannon.