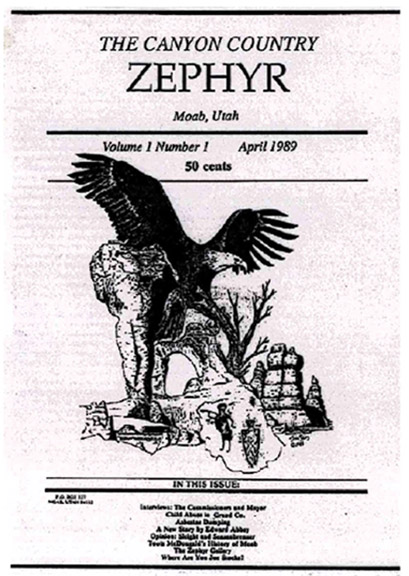

This story was first published in Blue Mountain Shadows Magazine under the title, Overland to Fort Moki, in the magazine’s 20th anniversary issue, Volume 34/Spring 2006. In 2018 it was published as the last chapter of the author’s second edition of the book, White Canyon, Remembering the Little Town at the Bottom of Lake Powell.

The National Geographic article referenced in the text was published in the April 2006 issue under the title, A Dry Red Season: Drought drains Lake Powell – uncovering the glory of Glen Canyon.

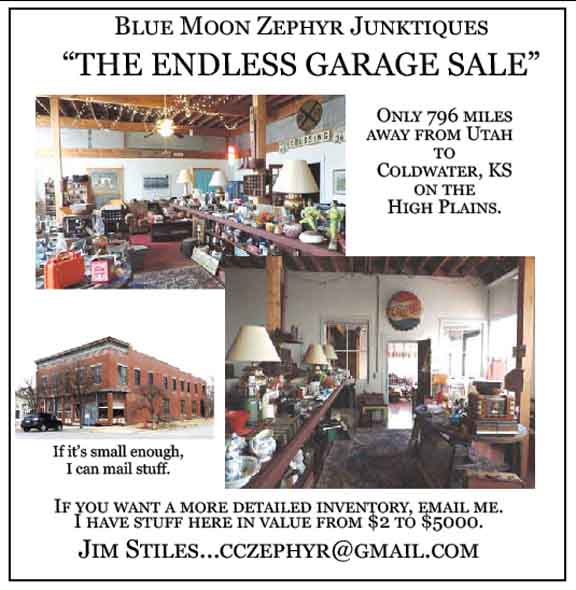

Photographs by the author, with additional images by Brett Timm, Edna Fridley, Charlie Kreischer, Beth Nielsen, and Jim Stiles.

By the end of 2004 the water level in Lake Powell had dropped more than a hundred feet. Seven years of drought had greatly reduced water flow into the lake. At the same time, an ever-increasing demand for irrigation and municipal water was sucking the lake dry. Utah, Arizona, California and Nevada all had straws in the water. Competition over who could get the most was intense.

And, the lake was disfigured by the receding water. An ugly bathtub ring outlined the full circumference of the lake. Beginning at the water level and reaching 100-feet high into the ledges, the red sandstone was bleached a sickly off-white color as the receding water sucked pigment from the ledges. It was an embarrassing thing to witness. Most lake enthusiasts had never dreamed that fluctuating water levels would leave such an unsightly scar.

There was economic damage too. The water was so low people couldn’t launch boats from the Hite Marina anymore and the place had become only a convenience store and gas station. Below the river bridges and at the mouth of the Dirty Devil River, the bare lake bottom had become a trashy and repulsive mud flat. Concrete boat ramps at the Hite Marina ended in the willows far short of the water. Weeds and hardy tamarack sprouts were taking root all along the receding shoreline.

But, for some of us, the fading fortunes of the lake were not all dark and gloomy. The dramatic drop in water level presented a possibility that intrigued some of us. If the water was that low, what had happened to the old Indian fort at the mouth of White Canyon? Was it possible that Old Fort Moki would be coming out of the water again?

THE WAY IT WAS

For Tom McCourt’s Zephyr article about White Canyon and his memories of that long forgotten little town, click here.

In November of that year (2004), my wife Jeannie and I, along with Leslie Nielson, a family friend, and Ranger Brett Timm from the National Park Service, hiked out on a rim between White Canyon and Farley Canyon and had a look.

I was so excited when I saw that old Indian ruin exposed to the sunshine. She was barely out of the water, but she had risen from the dead. That old fort was only a pile of rocks now, the ruin of a ruin, but I still recognized her. The high rocky promontory she once sat on was now a narrow causeway out into the lake for a hundred yards or more. Water lapped at the fort’s foundations, and she looked humbled, wet and beaten, but she was there where I could see her for the first time in forty years. It was a spiritual experience for me.

But while we could see the ruin, there was a great expanse of deep water between her and where we were standing. She was half-a-mile away, and without a boat, we couldn’t get to her. We took a lot of long-range pictures and had a little celebration anyway. We saw no other people at the lake that cold winter’s day and there were no boats on the flat blue water. As we looked at the resurrected ruin through binoculars, it occurred to me that it was possible that no one had been to the old fort yet. There were probably less than a dozen people in the whole world who knew, or cared, that she might have risen from her watery grave. So Jeannie and I began to plot how we might be the first to witness close-up what had happened to her in the past 40-years underwater. It posed a problem for people like us who didn’t own a boat.

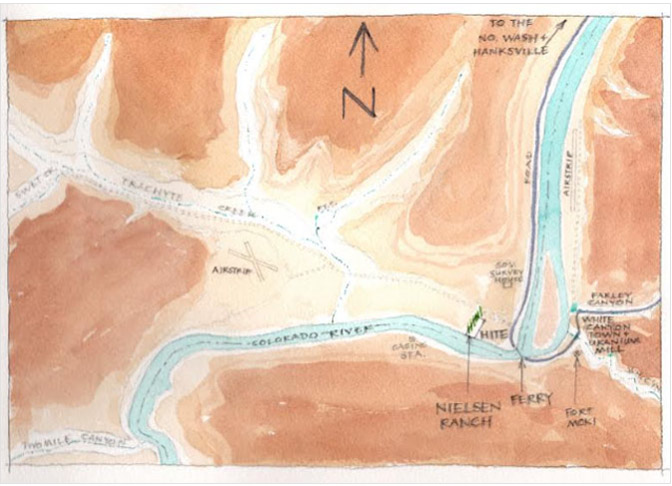

I studied some maps and found a possible way to get to the old fort overland. It would be a rough route, a hike of many miles while traversing raw, unexplored ground. But what the heck. On my 125,000-scale map, the distance was only an inch or two. I talked Jeannie into it. We were 58 and 57 years old at the time, but in pretty good physical shape, and besides, we hadn’t had a real adventure for a long time.

In the early morning of January 30, 2005, we parked our pickup truck at the end of the road in White Canyon Wash and struck out toward the lake. It was cold on the desert, and our plan was to hike down White Canyon as far as possible before scaling the canyon walls on the south side of the canyon. With any luck, we might be able to get within a mile or two or our destination before scaling the canyon wall. But, we soon found ourselves wallowing in mud. Recent rains and retreating lake water had fouled the bottom of the wash with a thick, greasy slime. We had to leave the canyon bottom much sooner than expected and climb to the top of the canyon rim.

(Leslie is the granddaughter of Beth & Ruben Nielsen.)

It was warmer up on the rim in the weak morning sunshine. But from where we topped-out we could see that going over the top of the canyon like that was going to be a much further trek than we had expected. It was obvious we couldn’t cover that many miles and be back to the truck before dark. What to do? We rested and ate a granola bar as we considered our options. Then, Jeannie, bless her heart, said she knew what that old fort meant to me, and she said I might be hard to live with if I didn’t get to see it after coming this far and getting this close. So, in spite of the miles and the perils of striking out into the rim rocks on our own, she bravely suggested that we should press on.

We knew what we were risking by going forward. It was January and cold on the desert. We had left many of the things we normally carried in our backpacks back at the truck to save weight. Expecting to be back to the truck before dark, we were carrying only the bare necessities and only a little water.

But, just in case we ran into problems, we had chosen this particular winter’s day because of the promise of a full moon. I told her it would be okay to hike in the dark. I remembered nights in White Canyon when I was a boy that were so bright my grandfather could read his newspaper by the light of the moon. With that hopeful expectation, and my amazing powers of persuasion (wink), we stepped out smartly and began covering the miles. We soon discovered an old washed-out scar of a uranium prospector’s road from the 1950s that took us almost all the way to our destination.

We reached the old Moki fort in the late afternoon and I was sad to see what had become of that magic stone castle of my childhood. Her twelve-foot walls had collapsed inward. She was now a pile of rocks with only three or four feet of her foundation walls still intact. Her toppled stones only a foot or two above the cold, flat water of the lake. That ancient temple on a hill was crumpled, broken and scattered now, but there was still a quiet dignity about her that made me feel humble and small.

The sky was winter gray, cold and empty. Very much like the last time I had been there, 46-years earlier, in December 1959. And like 1959, the canyon was perfectly quiet. The stillness was all-consuming, hauntingly lonely and very personal in the vastness of the Glen Canyon Wilderness.

And yet my heart rejoiced. I had never expected to see the old fort again. And now, there she was. She had changed a great deal, but the essence of her power, majesty and mystery still lingered. Her mound of collapsed walls resting triumphantly above the flat water, presiding once more over Glen Canyon.

Note his tracks in the still-wet mud

There were no tracks in the mud anywhere around the ruin, and with delight I recognized that we had accomplished something very dear to me. We were undoubtedly the first people to witness the fort’s remarkable resurrection. A fitting thing to happen, I thought. All those years before, on the eve of her destruction, I had caressed her walls and bid her a soulful farewell. And now I was the first to touch her again as she shed the mud and water of decades beneath the waves. I don’t think anyone ever felt a closer connection to that old Indian ruin than me. It was an honor to be the first to welcome her home. Jeannie and I spent an hour or more in quiet conversation and deep contemplation in the stillness of the canyon.

Then, as the sun was sinking low in the western sky, we decided we had better give some attention to our current situation. It would be dark soon, and cold. Jeannie is much smarter than I, and she suggested we stay overnight near the fort. There were large boulders nearby where we could take shelter from the wind, and the receding lake had deposited driftwood all around the site. Keeping a fire overnight would be easy.

But, true to my nature, I had made a schedule and I was determined to keep it. We had told our sons we would be home about midnight. We had no cell service there at the lake and no way to tell them of our change of plans. Besides, I had important things to do the next day and I was determined to do them.

We had traveled a long way since sunup, but we were still feeling strong and healthy. Then too, we didn’t have sleeping bags or blankets, and spending a night in the dirt around a campfire didn’t sound very inviting. So, I reminded my dear wife that tonight Mother Nature had promised to light our way home with one of those glorious full moons White Canyon is famous for. We struck out on our back trail, headed back to the truck.

The light was fading fast when we first heard thunder booming over the desert to the north of us, and we noticed, for the first time, the dark cloudbank beginning to cover the red sky of sunset. We hurried along, expecting that promised full moon to come up and light our way. But the moon didn’t show. With rising panic, I realized that the moon too, was being obscured by clouds. Distant lightning flashed, and thunder growled.

We were in big trouble. We were caught out on the open mesa with night closing-in all around us, fully exposed to the elements with no shelter and no flashlight. I have never felt so stupid. We had deposited our flashlights in a bag in the truck that morning in an effort to save weight. It could have been a fatal mistake.

As the last of the daylight disappeared, we left the trail and dropped down into a little cove at the side of the trail. We were better protected from lightning there, and from the cold wind. But we were done. Even fools like me know better than to try to negotiate canyon rims in the dark. We sat in the sand with our backs to the wind, hoping the storm would soon be gone. Between us we had one aluminum survival blanket and we shook it out and draped it over our shoulders and backs as we huddled together. But soon we were shivering. Jeannie suggested we cut the blanket in two. We each took half, removed our coats and wrapped our upper bodies with the aluminum foil before replacing our jackets. It was a brilliant idea and we were much warmer that way. But even then, after sitting on the damp ground in the cold wind for only a short while, we were both shivering again and we knew we might be hypothermic before daylight. And, if the storm caught us and we got wet, this cold January night might be our last. The wind was howling and the temperature dropping fast.

We had to do something. I told Jeannie I was going to start a fire, a foolishly hopeful sentiment it seemed, there on that rocky mesa without any trees. The very thought of all that driftwood back at the lake made me want to cuss. What a fool I had been. But we couldn’t go back there now. It was as dangerous to go back as it was to go forward. Better to chance freezing than walking off a ledge in the dark.

Using the light of distant lightning flashes to guide me, I walked a few yards down our little cove and began kicking up sage bushes, tumble weeds and Brigham Tea bushes. Luckily, I was wearing a good pair of boots and roots embedded in dry sand gave up easily. I soon returned to my sweet wife with a big armload of stickery fuel for a fire. Jeannie, being a woman raised around horses and the great outdoors, had dutifully prepared a fire pit while I was chasing sage brush down the draw. She had scooped out a depression in the sand to better control a fire and help keep the wind from scattering the ashes. We crumpled up tumbleweed and dry sage twigs and soon had a fire.

But sage is lousy fuel for a fire. It burns hot, but it’s like burning cardboard. A sage fire must be tended constantly and it takes a whole lot of sage brush to keep a fire going all night. I must have kicked up half-an-acre of sage and Brigham Tea that night, and my exertions probably kept me as warm as the fire did. Jeannie, for her part, did something remarkable. She gathered a few flat rocks and began putting them in the hot coals. When they were hot, she would scrape them out of the fire and bury them in the sand where we were sitting. Take it from someone who knows. When you are caught out in the elements on a cold winter’s night, there is nothing better than a warm sandy place to sit.

The far-off flashes of lightning and the whistling of the wind were worrisome, but after we said our evening prayers, the distant storm subsided. God was good to us, as always. It was still a cold, dark night, but we were finally able to relax. We even laughed and joked a little. I reminded Jeannie we didn’t have cell phone service, and since we couldn’t tell the boys we were okay, they might have the sheriff’s posse out looking for us by morning. She said we had a more serious problem than that. Without cell service we couldn’t order pizza. What a woman. And, she is kind. Not once did she remind me about all of that lovely driftwood and those big sheltering rocks we had walked away from back at the lake. She never said “I told you so” or called me stupid, or anything of the sort, even though I deserved it. Every man should have such a woman.

The sun came up big, warm and glorious the next morning. From where we were, we could see that had we continued on down the mesa in the dark, we might very well have stepped off the rim and died that night. We had done the right thing by staying put and making do.

Jeannie had trouble walking that morning. She had foolishly worn a new pair of hiking boots the day before and overnight her feet had swollen. Her toes were badly blistered. I felt terrible because I hadn’t realized the extent of her discomfort or her injuries. Once we had committed to go the whole distance, she had been quiet, brave and resigned to her misery, only stopping a couple of times to “rearrange her socks,” she said.

She limped the first miles that morning, and walked that last sandy mile to the truck in her stocking feet, carrying her boots in her hands. We had a good first-aid kit in the truck and she was able to clean and dress her wounds, and she healed completely in only a few days. We got back to our truck about ten that morning and drove home quickly to tell our sons we were okay. We were happy they hadn’t called search and rescue.

We were able to go back in April of that same year (2005) in boats. My aunt and uncle, Jack and Melba Winn, cousin Janis Winn York, her husband Rick, and other members of her family, and Leslie Nielson and members of her family, were with us. We had a good reunion and spent a few hours reminiscing about White Canyon Town, Glen Canyon and the Hite Ferry. It was a beautiful day and cotton ball clouds were dragging shadows over the flat blue water of the lake.

We had been there about an hour when our daydreams and family remembrances were interrupted by the intrusion of a noisy little motor boat. The boat came ashore and two young men got out and started up the mud bank to where the old fort waited. One of those young men had a copy of my White Canyon book in his hand and was using the crude, hand-drawn map to orient himself with his surroundings. One of the young men in our party walked over to him and said, “The guy who wrote that book is sitting on that rock over there.” They both came over and introduced themselves. They were Chris Peterson, President of the Glen Canyon Institute, and Daniel Glick, a reporter for National Geographic. Mr. Peterson was escorting Mr. Glick to help him do a story about the low water levels of the lake and the things the low water was revealing.

Of course they were interested in interviewing our group for the National Geographic story. We all laughed that it must have been fate that put us all together there that morning. What were the chances? In the shadow of the ruins of old Fort Moki, they were able to interview three generations of people who knew and loved Glen Canyon, all in one setting. It was a remarkable experience.

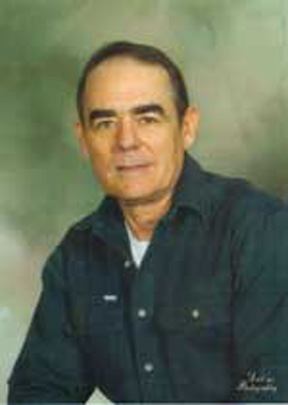

Author photo, April 2005

Then, something amazing happened. While being asked about my experiences with Fort Moki, I mentioned that before the lake, the flat sandstone shelf the old fort was sitting on had several pioneer inscriptions carved into the stone like names chiseled into a sidewalk. Mr. Peterson asked where. I pointed at a spot and said, “Over there.”

The man went back to his boat and returned with a wooden boat oar. He began, ever so carefully, scraping away the three or four inches of dry mud and silt like he was using a snow shovel. And there they were! Names and dates from the 1800s, perfectly preserved like they had never been under the water. The man with the boat paddle howled with delight and the National Geographic reporter smiled, shook his head and muttered, “I don’t believe this. I don’t believe any of this.”

Jeannie and I haven’t been back to see the old fort since that amazing day in April, 2005. Fort Moki belongs to everyone now. But I am so proud my precious Jeannie and I were brave enough, tough enough, and foolish enough, to attempt that overland expedition in the dead of winter to be the first to touch her resurrected walls. We hope the National Park Service will forgive us for burning that half acre of sagebrush. It was surely a cheaper option than sending a search and rescue team to recover our frozen bodies.

We do hope all who visit Lake Powell and the ruins of Fort Moki will appreciate our love for the place and treat the ruins, the lake, and the canyons with respect. White Canyon is still God’s red rock Garden of Eden. And it will remain so, long after you and I are gone.

An update to the story:

By 2020 the water of Lake Powell had retreated until the Colorado River had reclaimed her old channel in the upper regions of Glen Canyon. Unfortunately, the old landscape of the canyon had been replaced by a deep and massive mudflat. Silt from the lake was almost 100 feet deep around the rocky promontory where the crumpled walls of the old Moki Fort were exposed. We would never have believed it at the time, but when Jeannie and I were there in 2005, the water surrounding the old fort was only a few feet deep. As the water receded, it revealed mud reaching almost to the walls of the old fort, and White Canyon was filled with mud for a mile or more up the narrow channel.

In August 2021, a massive flood down White Canyon was so severe that a bridge over the canyon was badly damaged and State Road 95 was closed for a few months. When that happened, the raging water blowing out from the mouth of the wash into Glen Canyon, spilled over the ruins of the old fort and completely washed it away. Not one rock remains today of the most famous Anasazi ruin in Glen Canyon. She miraculously escaped the man-made waters of Lake Powell, only to be scattered and buried in the mud by Mother Nature. The author has seen pictures, but hasn’t had the heart to witness it for himself.

Tom McCourt is a native son of the canyons and deserts of Southeast Utah. Before Lake Powell flooded Glen Canyon, he spent a portion of his childhood at Dandy Crossing, playing cowboys and Indians amid the ruins of Cass Hite’s old log cabin. Tom has written four other books about the people and places of Southeast Utah. He is a graduate of the University of Utah and served proudly as an officer and a gentleman in the United States Army.

To read ZEPHYR chapters from Tom’s remarkable book “Last of the Robber’s Roost Cowboys: MOAB’S BILL TIBBETTS,” click here

TO COMMENT ON TOM McCOURT’S STORY, PLEASE SCROLL TO THE BOTTOM OF THIS PAGE. I’D ESPECIALLY LIKE TO HEAR FROM ANYONE WHO IS STILL ALIVE WHO REMEMBERS FORT MOKI. IF YOU HAVE ADDITIONAL PHOTOGRAPHS, YOU CAN SEND THEM TO ME BY EMAIL: cczephyr@gmail.com

And I encourage you to “like” & “share” individual posts.

Why they can’t just leave the site alone is beyond me,

but that’s what Facebook likes to do.

ALSO NOTE: I post old photographs and stories from our 25 year old archives every day. Pictures from Herb Ringer, Edna Fridley, Charles Kreischer.. even a few old photos from my Dad. So if you want to stay caught up on our historic photo collections,

be sure to “follow” us on Facebook…Thanks…Jim

https://www.facebook.com/FansoftheCanyonCountryZephyr/

https://www.facebook.com/profile.php?id=100086441524150

And check out this post about Mazza & our friend Ali Sabbah,

and the greatest of culinary honors:

https://www.saltlakemagazine.com/mazza-salt-lake-city/

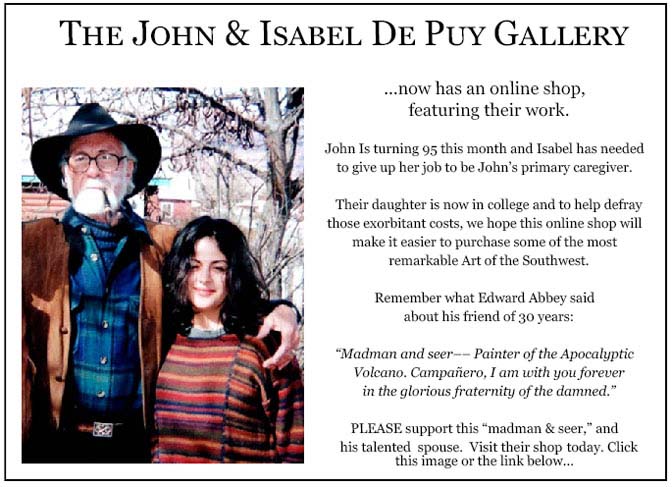

More than six years ago, The Zephyr, me & four other individuals were sued for defamation by the former Moab City Manager. Faced with mounting legal bills, my dear friends John and Isabel De Puy donated one of John’s paintings to be auctioned.

ALL the proceeds went to our defense.

Thanks to them, our bills were almost completely covered.

Now I’d like to return the favor. Check out the link below and their online shop… JS

https://www.depuygallery.com/

https://www.canyoncountryzephyr.com/

TO COMMENT ON TOM McCOURT’S STORY, PLEASE SCROLL TO THE BOTTOM OF THIS PAGE. I’D ESPECIALLY LIKE TO HEAR FROM ANYONE WHO IS STILL ALIVE WHO REMEMBERS FORT MOKI. IF YOU HAVE ADDITIONAL PHOTOGRAPHS, YOU CAN SEND THEM TO ME BY EMAIL: cczephyr@gmail.com

One of the most interesting historical Lake Powell articles I’ve read!! the pictures are unbelievable and especially now that the areas taken are no longer there. Nice work putting this together so we who will be unable to visit have a window info how it really was.

Thanks Donna. I always appreciate your input. And I’m genuinely envious of the Western history that resides in your heart and soul. And after 94 years, you’ve really experienced and remembered the West as few of us can. For those not familiar with Donna, she and her husband Gail moved to Las Vegas in, I think, the mid-1930s. Amazing. Consider THAT transformation.

Thank you Jim great story and Tom definitely has quite the wife!

Shannon. Thanks. You’re becoming one of The Zephyr’s most faithful readers. I really appreciate your interest.

Wow, what a coincidence, I just bought Tom McCourts 2nd Edition book yesterday.

I have a much stronger understanding of the love that these people had to their places among the ancient ruins before the inundation of Lake Powell. I was just a kid when the dam was completed and Pop bought a boat so we could visit the lake every year. Now that you’ve shared these precious stories along with the maps and photos, I want to read every book about the place and experience that I can get my hands onto. Maybe I’ll even luck out and find some pictures to share from our adventures down there.

And just that fast, the story of a whole group of people and things is gone. How precious are the Record Keepers…those pictures, those words will remind our descendants that we aren’t the first and our actuality may well disappear in a flood, or a tsunami or a volcanic eruption. Thank you!

Thanks Lurell…I’m grateful that I have all these resources, like Tom McCourt, to keep the memories alive. More coming soon from Tom, as well as Herb Ringer, Edna Fridley and a new addition coming soon

great story, but yes, sad in it’s own way–I wonder if the rock with the pioneer inscriptions also disappeared. Being grateful for what we knew in the “good ol’ days” takes on extra meaning when what you knew isn’t just changed, but has actually disappeared entirely.

A lot of them did, but I remember that when the reservoir first went down, we checked out the exposed parts near Hole in the Rock, and found some of the pioneer inscriptions that had been underwater for 40 years. And I think they would have been above the sediment layer because it was so far down river…

A fascinating read, as ever, Jim.

Who am I to contradict the fabulous Sir Tom McCourt? Well, I’m going to anyway.

I believe the ultimate demise of dear old Fort Moki occured well before 2021.

I’ll explain how, why and when in a later comment. if the cat gives me an uninterrupted 90 minutes on the keyboard …

I believe you are correct that it was gone before 21, in 8/2020 I was at this location and no sign of Ft. Moqi was present. It seemed the entire area was eroded down to slickrock and boulders in the location it Should have been. I wish I had had these photos to compare at the time. On Labor day weekend of ’21 right after the major flooding in Hanksville I went past again, the water level or rather the down cutting of the river was significantly 30? Feet lower than it had been in 2020. Crazy how this upper end of the lake has changed as the water has dropped.

Fantastic story and adventure. So much heritage that the decision makers were willing to sacrifice to a concrete plug. Even when built it was known to have a finite lifespan. I remember reading while in high school in the 60s about the sedimentation in reservoirs that, in time, would diminish their usefulness! So the 100-foot bathtub ring is no surprise.

Even the store and gas station at Hite is now closed; I visited there this last summer.

Exactly. In the 1980s there was a series of reports called The Lake Powell Project and I bought several of them. One dealt with sedimentation and was already predicting that the upper end of the reservoir would be silted in by 2000 or thereabouts. They were spot on .., they knew what was coming. And by the late 60s and early 70s, common sense was starting to prevail. Proposed dams in the Grand Canyon were cancelled and had Glen Canyon been proposed a decade later, it would never have been built.

No matter the consequences, not building the dam would have been the better option. But that dream world of Glen Canyon that so few knew about ..,”the place no one knew”… would still have been lost. It would have shared the same fate as Arches and other previously “unknown gems” of the National Park Service. Without the dam, there would be the same crowds, the same “reservation only” scenario that you see today. The reality is, between 1946 and 1963, there was a very magical moment, known to few, would leave a legacy that we all still long for and dream of, but would never have experienced.

Thanks for the Tom McCourt update. Fort Moki was special. Tom Martin had also recently discovered, to my great dismay, that the ruins had been swept away since McCourt’s visit in 2005. A book could be written about what was Glen Canyon’s foremost tourist attraction. The historical inscriptions (and Rock Art) on, or near the Fort were recorded by Crampton before they were inundated and are available in his report online.

Random comment, I was intrigued over the tenuous possibilities suggested by the Dec.13 (18)93 inscription by Foote (and?) Reed. Sheriff turned outlaw Phil Foote was reported in contemporary newspapers to have made an unlikely 1892 trip down Cat on a log raft. There is of course a more likely overland route from Spanish Bottom. I am a huge fan of Phil and Gussie Foote. Among other adventures the future Madam Gussie walked a tightrope across the Colorado River;-). Another random comment…I believe that a spectacular image of Fort Moki was likely taken by Charles Goodman but is mis-attributed (IMO) to William Henry Jackson at Beinecke Library and labeled “Near Junction of the San Juan and Colorado River.” https://collections.library.yale.edu/catalog/2011320

Tip of the hat, and thank you Jim Stiles for what you do and how well you do it!