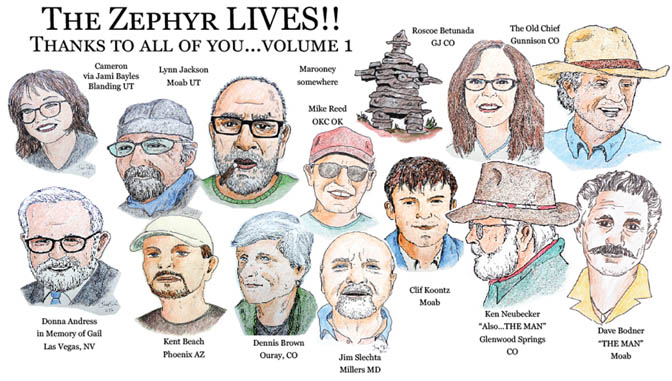

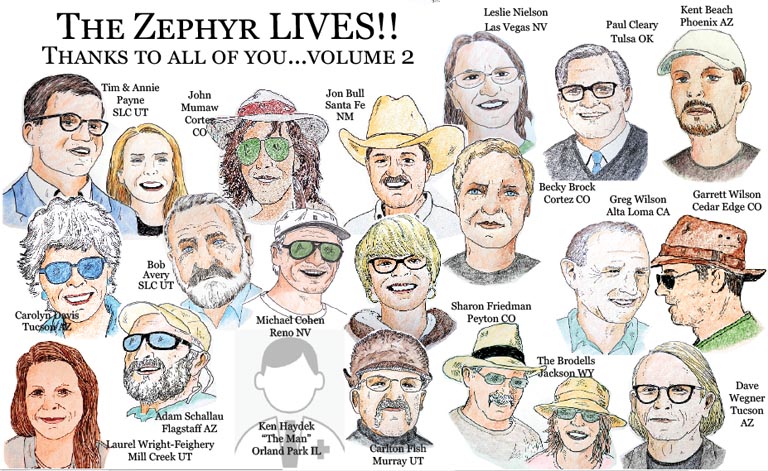

NOTE: Special thanks to former Grand Gulch Ranger Becky Brock. The information and photographs she was able to provide me, regarding the BLM’s Grand Gulch program in the 1970s, and specifically the details of the crash, have contributed greatly to this story. Thanks Becky…JS (all photos are courtesy of Becky except where noted)

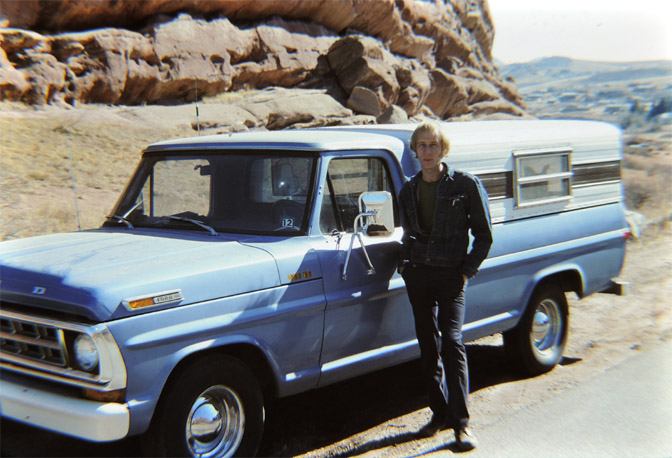

At first glance, very few casual observers would have taken Jim Conklin for the heroic type. Physically, he didn’t even come close. In the mid-70s Jim had already worked several seasons for the National Park Service after a stint in the military. But he was, by his own admission, one of the skinniest men in the Intermountain West (though I must have surely run a very close second). Jim was more than six feet tall but I doubt he weighed 140 pounds, soaking wet. He was a gentle and sensitive soul and took the constant kidding he received from his friends with his own self-deprecating wit. He was certainly no “tough guy.”

He would tell “skinny stories” about himself. Once, while on a date, he told his companion that he was a military veteran. He claims she looked him over and replied, “What were you…a prisoner of war?” A couple years before I met him, he was a seasonal ranger at the Grand Canyon’s South Rim. He worked many days patrolling the trails and viewpoint at the Desert View Watch Tower. One afternoon, he was standing alone near the overlook when a piercing voice with a New Jersey accent shattered the silence…

“Harvey! HARVEY!!!(pronounced ‘Hahvey”) Look…do you see him? Do you see that skinny ranger? My God, Harvey, he might be the skinniest ranger I have ever seen! Oh my GOD!”

There were hundreds of other tourists milling about, enjoying the spectacular views, but they all turned away from the Grand Canyon to stare at the “skinny ranger.” He was mortified. Later he told me it felt as if he were naked. Or covered with warts. “Everybody was staring at me, Stiles. It was awful.” It was one time where his self-deprecating sense of humor and good nature failed him. But he endured the moment and tried to eat more fatty foods, but to no avail. When I met Jim Jim Conklin in October 1975, he was still a pretty slim guy. Jim Stiles

I’ve told this story before, but that autumn, my dog Muckluk and I were wandering around southern Utah, trying to find a warm place to spend the winter. Days earlier, I’d walked into the visitor center at Natural Bridges National Monument and the ranger on duty, Dave Evans, thought I looked rather cold and pitiful; he offered me a cup of coffee and I wound up sleeping on his couch and hanging out for a couple weeks. Ultimately Evans introduced me to the NPS staff in Moab and I secured a volunteer job with the Park Service at Arches.

But one afternoon at Bridges, sitting on Dave’s front steps; I heard someone come around the corner of the building and saw a very skinny man, dressed in full SCUBA gear, complete with wetsuit, the tank, googles—the works— running toward me at a full gallop. He shot past me — didn’t even pause to say hello. I was bewildered; there wasn’t a body of water to submerge oneself in for 50 miles. But a couple minutes later, the Frogman returned, and this time, he paused to say hello. It was my introduction to Jim Conklin.

We soon became best friends and I learned there was so much more to the man than his somewhat scrawny physique. He was one of those rare individuals who was genuinely kind, but didn’t realize it. It was just who he was. His generosity, his concern for others, his integrity, and his honesty, were never meant to impress anyone. He wasn’t in any way a prototype of today’s annoying “virtue signaler” (Look at what a good person I am!). He was simply a good person.

He was living briefly in the residential area of Natural Bridges National Monument, but it was part of an arrangement the Park Service had made with the Bureau of Land Management (BLM). He had started work in August 1975 as a backcountry ranger for the Grand Gulch Primitive Area, an area administered and protected by the BLM.

Thanks to the creation of Bears Ears National Monument, which encompasses all of Grand Gulch and Cedar Mesa, most of the planet knows that some of the most outstanding archaeological treasures in the world can be found on that high mesa. Massive marketing campaigns by the Industrial Recreation Industry, allegedly in support of the monument, but with profit margin increases in their souls, has now brought the world to Grand Gulch.

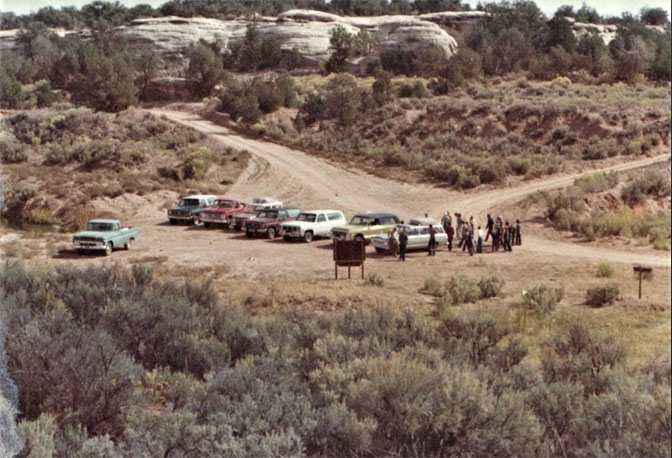

When Conklin came on duty in August 1975, the area was known to a tiny fraction of the tourists who come now. But in the 1970s, Cedar Mesa was a target for individuals invested in the illegal pothunting business. It had been illegal to remove these artifacts from public lands since the passage of the Antiquities Act in 1906. But the law had no teeth in it. The penalties for being caught pothunting, or even worse, grave digging ancient sites, were minimal. The best and only way to stop or reduce these crimes was to increase the presence of BLM rangers. In 1975, the Grand Gulch Primitive Area had six full time rangers, all of them committed to protecting these many invaluable sites.

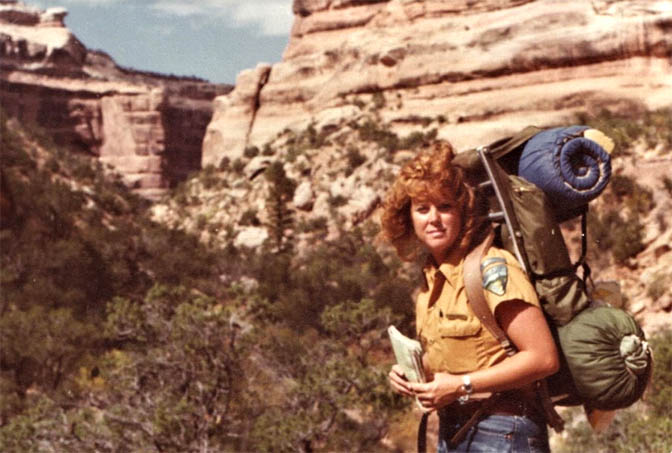

For Jim Conklin, being a backcountry ranger and doing something truly worthwhile, made it feel like the ultimate dream job. He came to Southeast Utah, full of hope that he could make a difference and with an unbridled excitement, simply because he loved the canyon country of Utah; he looked forward to exploring the canyons he was hired to protect. But as one of his co-workers, Ranger Becky Brock, would note many years later, “Jim unknowingly walked into a hornet’s nest.”

*****

The vandalism inflicted upon the archaeological sites across Cedar Mesa in the 1970s and into the ‘80s could not be understated. Earlier in the century, many of the local residents had gathered up artifacts, honestly unaware of the damage they were causing, and simply felt that removing these beautiful works of art from the elements was a noble gesture and a way of protecting them. It was a point of view shared by the academic world; even in the 1940s, university professors utilized the knowledge of some San Juan County Anglos to lead them to various sites that they could document and study.

But other “collectors” were more interested in their resale value and profitability, and the damage they caused created a great deal of alarm among archaeologists and the government assigned to protect them.

Bill Lipe was one of those concerned archaeologists and in the 1960s, he was working out of the Museum of Northern Arizona in Flagstaff. Lipe later wrote that, “I have spent six field seasons since 1967 doing research in the Cedar Mesa-Grand Gulch area of southeastern Utah, a substantial part of which has been designated the Grand Gulch Primitive area by the Monticello District of the Bureau of Land Management. The BLM now has a ranger team operating in this area and is developing a management Plan. I have been an advisor to this program since its inception.”

It was, in fact, due to his research and lobbying efforts that Grand Gulch received its official designation as a “Primitive Area.” In 1974, Bill Lipe was also instrumental in convincing Congress to designate $90,000 in “emergency funding” to hire the “ranger team” he refers to. But the emergency funding expired after that fiscal year, and the BLM was expected to find monies within the agency to continue these necessary protections.

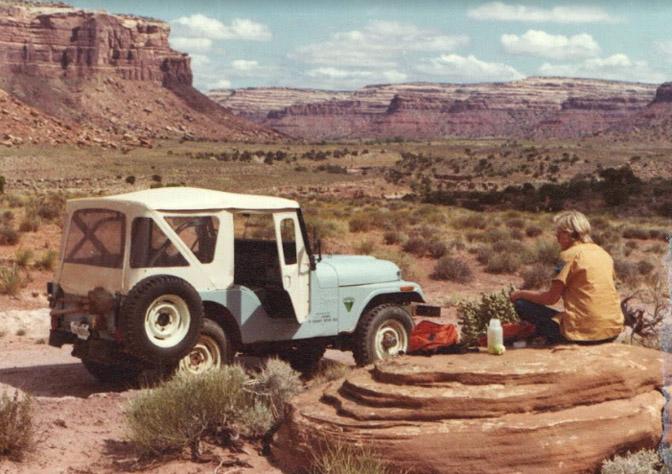

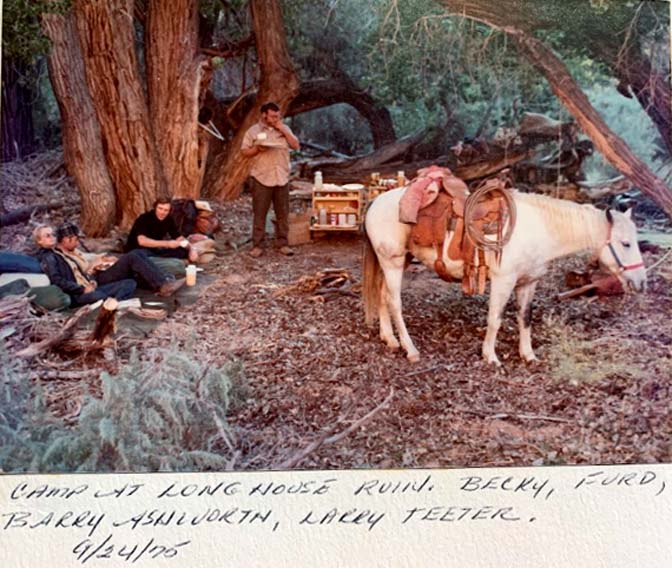

Though the BLM lacked the authority to impose serious fines or prison time for pothunters, the hope was that the regular presence and patrols by the Grand Gulch rangers would help to intimidate the illegal pothunting industry and force them to stop attempting further desecrations. The rangers tried to cover every part of the Gulch; they traveled on foot, on horseback, and even used kayaks at times via the San Juan River to access the lower parts of the protected side canyons. But the BLM also employed another means of travel for its rangers. It was even recommended by Lipe, though he had concerns of his own. Lipe wrote, “Extreme caution must be used in motorized patrols, especially with the helicopter. Overflights of the Primitive Area are not now being made, nor should they be.”

He added, “Hikers should not be “landed on” except in an emergency, and only vehicles on main access roads should be contacted in this way.”

But some of Lipe’s admonitions were ignored. Starting in late 1974, the BLM contracted helicopters for surveillance of the Primitive Area. Its purpose was to locate and identify vehicles and attempt to determine their reason for being there. It got to the point where everyone visiting Cedar Mesa might be a suspect.

Becky Brock, one of the first rangers hired to patrol Cedar Mesa, had misgivings about the program from the beginning. In a recent interview Becky told The Zephyr about those concerns and noted that when the helicopter program began…:

“…There was no written helicopter policy or helicopter safety program. For instance, prior to the crash we flew in cut-off jean shorts, tennis shoes, and t-Shirts, with the doors removed for better visibility and air flow in the cabin. Radio communication was non-existent in most of 1974-1976 flights and/or it was always breaking down.

“The choppers had mechanical issues from the get go, but we kept flying. Some of the pilots took chances showing off their skills…. Some had just returned from military duty and were daredevils.”

Conklin was vaguely aware that helicopters were being used on some level, but not long after he started work for the BLM, he became concerned that the program was not only too dangerous, but that it was an invasion of privacy to the honest backpackers who had come to to the Gulch with nothing but good intentions. Conklin’s first flights were in the fall of 1975. He and I met at almost precisely the same time that Jim grew increasingly worried. Jim’s integrity and candor were a part of his “heroic” side. He was never afraid to express an opinion, even to his work superiors, even when he knew it could create negative repercussions for him. I recall Jim expressing his worries to me as early as November 1975.

He said, “Stiles, we’re landing on backpackers in the middle of nowhere, warning them of the penalties for pothunting, when there was no reason to believe they were doing anything but carrying really heavy packs to go see some ruins. It’s not right….Plus, these choppers are not safe. They scare the hell out of me.”

Conklin had done some research on the type of helicopter the BLM was often contracting. Sometimes the BLM utilized Bell Jet Rangers but often they often contracted Hiller 12Es— at the time, this specific type had a worrisome safety record. According to Brock:

“The choppers were under contract with the BLM, which was cheaper than using the Office of Aircraft Services (OAS). The chopper contract included a pilot. We had several different chopper types and pilots. The OAS had been established in1973, by the Secretary of the Interior, to ‘raise the safety standards, increase the efficiency, and promote the economical operation of aircraft activities in the Department of the Interior.’ The OAS certified pilots and certified aircraft were expected to be safer than non-OAS aircraft and pilots because OAS required a higher level of aircraft maintenance and pilot OAS certification.”

Brock even warned her supervisors that the Grand Gulch contracted choppers had been plagued with mechanical trouble since the beginning and that she preferred a government chopper from OAS with a government pilot.”

Like Beck, Jim took his concerns to his supervisors but there was little if any incentive by them to change or cancel the program. To them, the choppers were a great success. He was told to get in the helicopters and do his job. Later Ranger Brock reflected on what little training any of them had received before the surveillance flights were initiated:

“The only safety training I remember is a hands-on session conducted by BLM Moab Aviation manager, Bob Dalla, on 10/24/74, in Bullet Canyon at Perfect Kiva. The chopper had shuttled in supplies for an archaeological stabilization project along with Dalla and other BLM employees. I don’t remember any other helicopter safety training except the obvious….duck your head entering and exiting the chopper whether or not the blades were in operation. I don’t remember formal helicopter safety training for future employees, including Conklin. I remember that those of us that had worked in 1974 simply took ‘new’ employees up in the chopper in subsequent years to show them the area and how to ‘patrol.’ We probably told them to duck their heads under those blades.”

Other mechanical problems arose with the helicopters that added more worry to an already risky operation. One of her supervisors, Bob Turri, shared his concerns about the program, especially the safety issues, but lacked the authority to make any changes. He later told Brock of the incidents that had left him so troubled. According to Brock:

“Bob said he remembered many problems with the contracted helicopters at Grand Gulch. On one occasion, Bob drove to Blanding to board the chopper for a flight but found that the pilot had been up all night working on mechanical issues with the chopper. The pilot was ready to board and go, but Bob said he told the pilot he would not fly that day because the pilot had gotten no sleep all night.

“On another occasion, he was on a Grand Gulch helicopter flight and the pilot set down on Cedar Mesa because he didn’t think he had enough fuel to get back to Blanding. Bob said the pilot didn’t trust the fuel gauge. So, they landed and the pilot used a dipstick to determine how much fuel was left in the fuel tank. He thought there was enough fuel, so they went ahead and flew back to Blanding…And once, Bob said the pilot took both hands off the stick to light a cigarette and smoked it for the rest of the flight.”

These kinds of stories circulated among the Grand Gulch rangers; some of them were unconcerned, but others, including Becky, Jim, and fellow ranger Cindy Rogero took them seriously and grew more apprehensive by the day.

*****

Jim Conklin was furloughed for the winter and the two of us took some road trips together. We helped move our friend Dave Evans, a ranger buddy at Bridges, to his new job at Carlsbad Caverns and there was plenty of time to talk. The topic of the chopper flights weighed heavily on Jim and he often spoke of the possibility that a faulty aircraft, a helicopter he knew was dangerous, might kill him.

He came back on duty in late February, but quickly learned that nothing had changed. The helicopter surveillance flights would continue. And often, the BLM would still use the Hiller 12Es. The first scheduled flight was Monday, March 14, 1976.

Just a few days earlier, Conklin and I had driven over to the west side of Horseshoe Canyon, via the old Green River road with its amazing ancient wooden bridge over the San Rafael River. I had never seen the Great Gallery before, though Jim had been there several times. Jim decided not to tell me when we were getting close; he wanted me to have that singular moment when I looked up and gazed upon this most extraordinary work of art for the first time. I think Jim was as thrilled by my reaction–the surprise of it–as he was to return and see the pictographs again. That was Conklin. We lingered into the early afternoon, then made the steep hike up the West Trail and the long drive home. He reminded me that he started work in just a few days and hoped he’d live long enough to visit Horseshoe Canyon again. He was that worried and that preoccupied with the risks.

When March 14, 1976 dawned, the skies were clear and calm—perfect conditions, weather-wise, for a surveillance flight. Becky Brock and fellow ranger Tim Oliverus flew in the Hiller12E from the Blanding airport to a site near the Kane Gulch ranger station. A wide flat pasture, not far from the Gulch HQ was perfect for landings and takeoffs, with few obstructions. Conklin was there when they arrived. The chopper was refueled and Jim swapped places with Oliverus. When they took off, a few minutes later, the pilot, Fred Wardell, was in the center seat, Conklin sat on the left, and Becky Brock occupied the right hand seat. The flight was supposed to last 2 1⁄2 hours.

Just before the chopper arrived, Conklin had drunk a very large mug of hot chocolate that Becky had brought him, and now, realizing they’d be in the air for a long time, Jim started to worry about, of all things, his bladder. On our many trips together, I knew Jim didn’t have the largest bladder on the planet. I believe I once grumbled at the frequent stops and made some sexist remark like, “Good God, Jim…you’re worse than a woman.” (I’d never say that today…aloud)

Jim expressed his urinary concerns to the pilot who assured him he could put the Hiller down at a number of locations. “Don’t worry, you’ll be okay.” The chopper and its three occupants flew east to Owl and Fish Canyons, then past the long gone bean farm, and past the Moon House ruin turnoff from Hwy 261. Conklin was impressed by the smoothness of the ride but he was bothered by the noise of the aircraft; it was much louder than he had expected and started putting his fingers in his ears to muffle the roar. The pilot had brought cotton along and stuffed his ears before takeoff. Now seeing Conklin’s distress, he pulled the cotton balls from his own ears and shared part of his supply with Jim. It helped but not much.

The Rangers spotted a few people on the rim of McClouds Canyon, circled them and concluded they were harmless. The pilot turned the Hiller south along Comb Wash to its intersection with the highway. They flew over the escarpment of Comb Ridge, then turned north at Butler Wash. With lots of flat ground ahead, Wardell turned to Conklin and asked if he needed to land. Jim was already feeling a bit uncomfortable. The hot chocolate had made its way south.

“Yes,” Conklin replied. “Anytime you want to put it down, I’m ready.” Fred, the pilot, saw a particularly smooth landing site ahead and nodded to his passengers. “We’ll put it down there.”

When they were within a hundred yards of landing, Conklin noticed a vibration or trembling of the aircraft that he had not felt earlier. It scared him, and he would later write in his report that “it felt unstable.” But he had little experience with helicopters or the way they should feel; they were within inches of landing and Conklin assumed they’d be able to touch down safely. It was almost exactly noon.

Suddenly the chopper rose violently into the air, almost a hundred feet, its nose facing east. Conklin recalled that the motor seemed to be “cutting in and out,” and sitting beside the pilot, he could see Fred fighting furiously for control of the aircraft. Becky screamed once, then again; the chopper was wildly out of control and Jim knew “we were going to crash.” The chopper pitched over on its right side and plummeted to the ground. Becky was on that side of the chopper and took the brunt of it. Wardell was bleeding profusely from a wound near his left eye. Conklin, in the middle seat, after “seeing stars” and feeling the incredible G forces of a brutal crash like that, realized he was in better shape than the others. The pilot unbuckled his harness and climbed out his side of the chopper, which was now facing toward the sky. Conklin unbuckled himself as well and exited via the left door as well. The pilot ran to Becky’s side of the copter. He could barely reach her to unbuckle her belt, but managed to pull Brock free from the Hiller.

Becky was now lying on the ground, face down, just inches from the crashed chopper. Conklin was concerned that the Hiller 12E might explode, so he grabbed Becky under her armpits and pulled her on her stomach through the sage and sand until he was sure she was clear of any fire risk The onboard radio which rarely worked anyway, was destroyed. The only option was to walk for help. Though Conklin was starting to feel pain in his lower back, it was clear that he was the only one among them who could move.

Jim was also upset with himself. He was afraid that his need to land had somehow caused the crash. He was almost in tears. But Fred assured Jim that he was not to blame; in fact, his bladder had saved their lives. The malfunction could have happened at any moment and at any altitude. Any higher and they would all have been dead. In his BLM incident report, Wardell later wrote, “The BLM should really be proud of Jim Conklin.”

Only 15 minutes had passed since the crash, but Jim Conklin started walking south along the Butler Wash road to get help. It was a fairly mild day, perhaps 60 degrees, and Jim covered almost 8 miles in just a bit more than 90 minutes. As he approached Highway 163 and the road to Bluff, he saw a pickup truck coming, and he flagged it down. The driver stopped and gave Conklin a ride to the sheriff’s office in Bluff. Deputy Sheriff Rudy and his EMT wife immediately headed for the crash site by ambulance. Conklin was with them to help.

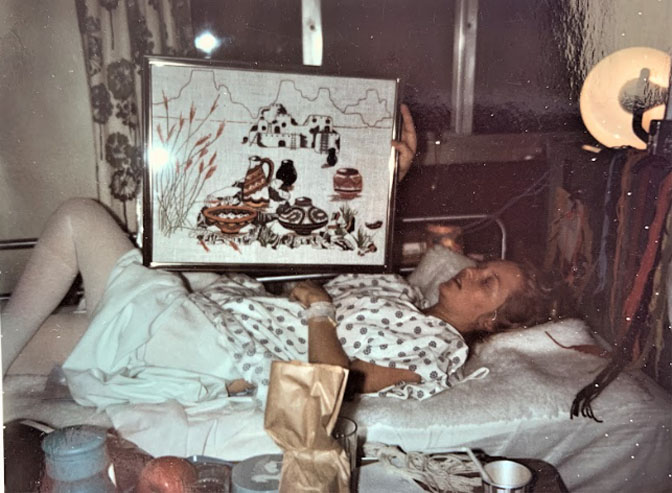

They reached Becky and Fred at 3:30 PM. Becky was still on the ground, with a severe back injury. She was transported to the hospital in Monticello and arrived around 5 PM. Her L1 vertebrae was crushed and it was thought at first she would need surgery. Four days later, Brock was transferred by ambulance to the hospital in Durango and placed under the care of an orthopedic surgeon, Dr. Kaufman. After X-rays and an examination of her injuries, Kaufman advised her that while he would normally have operated immediately to insert a steel rod in her back, because of her age and excellent health, he decided against it. Instead she was required to lie flat on her back for as long as two months and let nature do the healing. Fortunately the vertebrae fused on their own, just as the surgeon had hoped.

Becky recalled later that, “after the pain subsided, I learned to knit, crochet, cross stitch, embroider, & macrame flat on my back in that hospital bed. My days were very full between the hospital routine, visitors, phone calls, crafts, and letters.

On April 6. Jim and I paid Becky a visit at the Durango hospital. She was in good spirits but worried about Jim, who was hoping the BLM would put a stop to these flights. He was determined not to fly again. And despite his own pain, his greatest concern was that Becky would heal and return to normal life. After five weeks she was fitted with a back brace and she “gradually began to get out of bed and walk the halls.” Eventually she returned home but took a year off to fully recover.

The pilot, Fred Wardell, was sure he had lost an eye in the crash and his career as well, but his injuries turned out to be less serious than they looked. And Conklin, who had pulled Becky away from the crashed copter and then walked eight miles for help, was finally examined. After X-rays, he learned that he had cracked his tailbone upon impact.

All three of them were lucky to be alive. Later they learned that this was the first crash by a Hiller 12E that didn’t explode when it hit the ground. And the victims and the BLM learned that there had been enough crashes to raise alarms.

Later, Becky and the crew at Grand Gulch learned more about the cause of the crash. According to Brock:

“,,,the swashplate controls the movement of the cyclic to the top rotor blade. There are two rods from the swashplate to the engine (?) The left rod had broken. From the field investigation, Bob said it appears there was already a crack in the rod before it broke. In other words, we had been flying around with a crack in this rod.

“The Hiller had about 300-400 hours on it since it’s conversion from a military craft to a civilian craft; when this chopper was converted, it appeared to him that the rods to the swashplate were not changed or re-built…There is no regulation stating these rods must be changed when the rest of the craft is being converted from Military to civilian. There is also no regulation stating the swashplate & rods must be checked on pre-flight.”

Becky’s supervisor, Bob Turri, “talked to the lab technicians and asked them what would happen if the left rod to the swashplate broke. The technicians said the chopper would pull back & to the right & would crash on the right. This is exactly what happened.”

Becky Brock eventually returned to Kane Gulch, but she later recalled, “I remained off work the rest of 1976 as I wore the back brace while my spine healed. Strength and health gradually returned as I walked around the ranger station venturing a little further each day.

And she added this: “One final note about the crash, the BLM fired Jim Conklin on April 24, 1976, for refusing to fly helicopter patrols again. This was a travesty because it was Jim who saved our lives by insisting that we land, he dragged me away from the wreckage, and then walked seven miles to find help, all with a cracked tailbone.”

*****

It seemed impossible. After the crash, Conklin was grateful that no one had died and that Becky would recover, but he was also gripped by a grim satisfaction that his warnings about the risks had been ignored, and had resulted in this near fatal accident.

I was living at Arches in March 1976, still working as a volunteer, but I’d been hired as a seasonal ranger, with a starting date in April. I was unaware of the crash until Jim stopped by a couple days later. He was in pain from the tailbone injury, but was also angry that this disaster had occurred. “They just wouldn’t listen to me,” he said again and again. “To any of us…they put our lives at risk, with a faulty helicopter that we all knew had problems….we’re all for protecting the archaeology , but not at the price of a human life. They came so close to killing us,”

But Conklin, ever the optimist, was sure that at least now, the BLM would wake up, acknowledge its mistakes, and end this disastrous chopper surveillance. He felt confident that he had been vindicated.

At the next staff meeting, and the first since the crash, Jim expected management to offer some good news to its rangers. Instead, they seemed more gung ho than ever. The rangers had to “get back on the horse” and ride again. They couldn’t allow this incident to delay or cancel the chopper surveillance flights. Some of the rangers were still supportive. Conklin was appalled. And Jim, being the candid and outspoken man he was known to be, told his supervisors that he would not fly again. He was done. Enough was enough.

But six weeks later, on April 24, Jim was told Jim that he’d been fired.

Though some of the BLM management were sympathetic to Conklin’s position and quietly hoped something might be resolved, the new District Manager Gene Day was eager to rid his agency of this troublemaker. When Conklin first announced his refusal to fly, the BLM incredibly came back with a counter offer. They wanted to transfer him to the Little Sahara Recreation Area in western Utah, known for its sand dunes, and a popular destination of 4-wheelers and dune buggies. It was perhaps one of the noisiest and most heavily used BLM units in the state. It was the antithesis of Grand Gulch, where off road recreation was banned. Gene Day’s offer seemed not only bewildering but downright mean and cynical. In addition, at Little Sahara, chopper overflights were also mandatory for its BLM rangers. What was the point in even making such an offer?

But the BLM was unmoved. Jim Conklin, the man who hiked eight miles with a broken tailbone to get help after the crash, who pulled Becky Brock from the wreckage of the helicopter, knowing it could explode at any moment, was canned by the Bureau of Land Management. Becky Brock was stunned.

Later she recalled that Jim “was a kind man. Soft spoken, funny, personable, likable, smart, and great on a pack trip. He was a breath of fresh air.” She called his firing “outrageous.” But the decision had been made. He was out of a job.

Jim came by the Arches apartments and found me, the day after he’d been given his termination notice. We went to see Bill Benge (who would later become a good friend). It was my introduction to Bill and Jim asked for advice. Bill was a lawyer and the recently elected Grand County Attorney; consequently he was unable to offer his own services, but gave Conklin some recommendations.

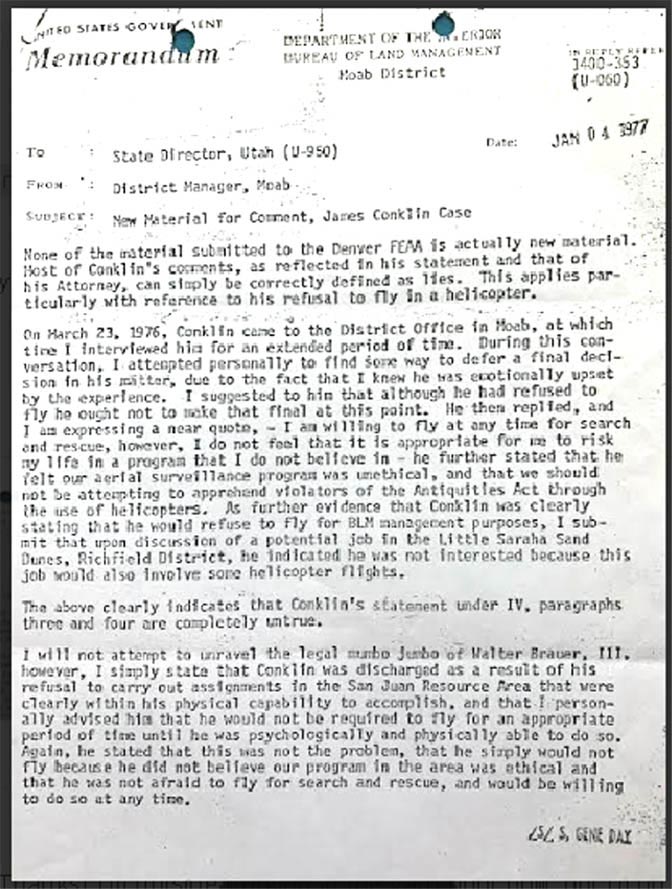

Conklin did retain the services of an attorney, but like so many legal issues, especially when dealing with the federal government, the matter went nowhere. Nine months later, District Manager Gene Day sent a letter to the BLM State Director. He said that “Conklin’s recent comments, as reflected in his statement and that of his attorney, can simply be correctly defined as lies.” He referred to some of the information from Conklin’s attorney and said he “would not attempt to unravel the legal mumbo jumbo.”

In some ways , it was Conklin’s honesty and integrity that doomed him. He had been terrified of flying in the Hiller12E and he knew of its shabby safety record. He had made that very point to me a few days before the crash. But Conklin also believed strongly, and he told Gene Day to his face, that the aerial surveillance was “unethical” and that he would not participate and risk his life in a program that he felt was an invasion of privacy. It was pure intimidation, plain and simple, against citizens who wanted nothing more than to enjoy the beauty of the area and its archaeological treasures. The BLM seized on that part of his statement, ignoring the fact that Conklin had already expressed fears about the chopper’s safety, even before the crash.

District Manager Day summed it up when he stated that Conklin would not fly for “BLM management purposes.” What hurt Conklin’s chances of winning this argument were diminished because of his own integrity. He told Gene Day that he would fly in a chopper, if its purpose was a search and rescue mission. In other words, Jim Conklin was more than willing to put his own life on the line, and fly in a helicopter he feared might be unsafe, if its goal was to provide medical treatment and provide aid to an injured person, or to rescue a stranded hiker. If someone was in trouble Conklin would have put his own fears aside and fly the mission.

Incredibly, it was Jim’s honesty and decency as a man that gave the BLM a way to fire him.

Conklin fought the BLM for years; his lawsuit went nowhere. For two years he was out of work and lived with his brother in Denver. He was also my best man at my first marriage.

*****

At Grand Gulch, the helicopters were back in the air, minus the Hiller that had augured into Butler Wash. And because, for the first in its history, a crashed Hiller 12E did NOT explode on impact, its three occupants survived. Becky Brock, after a year long convalescence, recovered from her injuries and returned to the Kane Gulch Ranger station (her husband was also a BLM ranger there). Later in 1976, Rangers Tim Oliverus and Ann Rasor transferred to the National Park Service and Ranger Lynell Schalk transferred to the BLM in Southern California.

In 1978 Becky resigned as well. Incredibly she was being told to fly again; one near fatal crash was enough for her. Ranger Cindy Rogero, who had been part of the program since its inception, also called it quits, specifically because she refused to fly in the choppers, especially the Hiller 12E.

1979…A BIG CHANGE—ARPA

As noted earlier, while the BLM employed as many as six rangers to patrol the Grand Gulch Primitive Area and its wealth of archaeological treasures, the rangers had very little if any law enforcement authority. The Antiquities Act, passed in 1906, made the removal of these artifacts illegal, but the law had no teeth. All the rangers could do was cite the violators and take them to the local court, where fines for these kinds of desecrations were pitifully small…a joke for sure. The BLM rangers were most effective simply by their presence which hopefully discouraged potential pot hunters.

But in 1979, the US Congress passed the Archaeological Resources Protection Act (ARPA). It gave the federal government the power and authority to impose heavy fines and even imprisonment for these kinds of crimes.

Former BLM Ranger Lynnell Schalk worked at Grand Gulch in the mid-70s when the chopper went down. Years later she talked to “Archaeology Today” magazine about her experience and the difference that ARPA made:

At Grand Gulch, the rangers were told to “go out there and stop the looting.” “Our main purpose was to get control of the problem in all of Cedar Mesa,” Schalk says, a 185,000-acre plateau broken by nine major canyons including Grand Gulch.

“It was a real crash course.” The rangers pursued pothunters on horseback, on foot, by jeep, and in helicopters. “We flew almost every day,” she remembers. But without law enforcement authority, the rangers could only notify local officers–based at least an hour away–when they caught violators. “You called the sheriff when you saw someone digging and he would come to the crime scene and make the arrest.”

Aside from the perils of the job, the biggest obstacle the rangers had to contend with when apprehending pothunters was that under the 1906 Antiquities Act the looting of archaeological sites was only a petty offense, less than a misdemeanor. “You didn’t have to serve time or be fined. It was a slap on the wrist,” Schalk says. “With the passage of the Archaeological Resources Protection Act in 1979, the looting and trafficking of archaeological resources was given a felony provision.” Before ARPA, the prevailing attitude was that it was acceptable to take artifacts from sites on public lands. The belief was held by many in local government. In fact, Schalk recalls a federal judge in Salt Lake City who refused to take archaeological cases involving only misdemeanor offenses.

But ARPA changed all that. Now the federal rangers had the authority to cite and even make arrests. But the new law came with a Catch-22. None of the original rangers at Grand Gulch had any law enforcement training and by the late 70s, any federal employee who was required to have law enforcement skills, needed the extensive training to go with it. Some federal rangers were lucky enough to be sent to the Federal Law Enforcement Training Center (FLETC) in Brunswick, Georgia. But many others seeking federal government jobs that required that kind of training were often on their own. Several academies catered to those needs and at a considerable cost.

Consequently, with the new regulations and ARPA, the BLM had to hire those applicants that met the new requirements, and at a considerably higher grade level. Salary-wise, the BLM could no longer afford the number of rangers they had used for several years. In addition, major BLM staff changes in southeast Utah rewrote priorities and soon, the helicopter flights ended as an unnecessary expense. But so did the number of staff. Now Grand Gulch was almost left on its own. Jeep and horse patrols dwindled. Forty years later, the “ranger presence” on Cedar Mesa is minimal, even as Bears Ears National Monument, with a total acreage ten times larger than Grand Gulch, draws more tourists to the place that its monument designation was intended to protect.

What’s next in this never ending human folly? Governments come and go, and priorities rise and fall. One bureaucracy replaces the last one. Ideologies swing wildly from one end of the pendulum to the other, as the years and decades pass. What’s next?

EPILOGUE

Jim Conklin left the BLM in April 1976. He lived for part of the next two years at his brother Bill Conklin’s home in Denver. Jim tried to get work in the private sector, but without any luck. Employers kept telling him he was “over-qualified.” Finally Jim sent a letter to the governor of Colorado— Richard Lamm at the time. Jim had graduated from the University of Colorado, so he wrote the governor, asking him to revoke his Bachelor of Arts degree.

“Since everybody tells me I’m overqualified for the jobs I apply for, it seems to me that the ONLY way I will ever get hired is to be less qualified. Consequently, he demanded the governor delete his academic record so that Jim could get hired somewhere, even if it was digging ditches. Conklin noted that digging ditches probably paid better anyway.

The governor failed to tear up his diploma but the local media had a field day with it. The story was carried in the “Denver Post” and the now-departed “Rocky Mountain News,” as well as local tv. In June 1978, Jim came to Moab and Arches to be my Best Man at my first marriage, But later in the year, I got a letter from him. The return address on the envelope said: “Guess where I am.”

As a former permanent employee of the federal government and as a military veteran, he had reinstatement rights under the civil service laws. Conklin was hired as a ranger at Carlsbad Caverns National Park in New Mexico. It wouldn’t have been his first choice—he spent most of his days 500 feet underground—but it was a job. He was working again. In February Jim was married in the caverns and this time I was his Best Man. He and his wife had two girls. A few years later, Jim accepted a job with the Department of Energy near Carlsbad as its official photographer. Conklin was brilliant with a camera and the job suited him, even though it was at the nation’s only deep underground radioactive waste site—the Waste Isolation Pilot Plant. He once wrote to me, “Now, not only am I underground a lot, I even glow in the dark.”

Every Christmas I’d receive one of his homemade cards with pictures of his daughters; it was his way of staying connected, though in the pre-internet days, neither of us were consistent letter writers.

But I failed to receive a Christmas card from Jim in 1991, and it worried me. I meant to write to him, but I was neck deep in Zephyr ‘stuff,’ in its early years and forgot. Finally in March, I received a short note that Jim had died on October 23, 1991. He was not even 45 years old.

I was having breakfast at the Main Street Broiler when I read the note. The Broiler was owned and operated by Debbie and Carl Rappe and I remember I was so shaken that I walked back to the kitchen, sat in the corner, and cried my eyes out; Debbie tried to console me and flip pancakes all at once. It made no sense to me. How could Conklin be gone? There was always something so comforting, just knowing Jim was out there somewhere. I was also disappointed in myself that I had not made a greater effort to keep in contact with Jim in the past year.

I had recently seen the Rob Reiner film, “Stand By Me,” based on the novella, “The Body,” by Stephen King. The film opens in the present day, as the main character, Gordie Lachance, sits alone in his car, lost in thought, with a newspaper in his lap. He had been shocked to read that his best friend from childhood, Chris Chambers, had been killed while trying to break up a fight at a local diner. The remainder of the film is a flashback to those times when they were kids, but in “Stand by Me’s” final minutes, the narrative returns to the adult Lachance, who was now a successful writer. Gordie sits at his computer searching for words. He remembered that, though he had not seen his friend in a decade, he “would miss him forever.”

“I never had any friends later on like the ones I had when I was twelve. Jesus, does anyone?”

Though Jim Conklin and I were a few years past twelve, I knew exactly what Gordie meant.

Incredible story.

Amazing history and story, now archived forever. Thanks Jim!

verrrry moving. whazz da’ werd? –> “poignant” might be a trifle restrained for such an in-depth compelling tale. thanks again, CCZephyr ~

Jim, thank you for honoring Jim Conklin with your ability to make words matter. You did an excellent job researching and compiling the data.

This is a story that still tears me up too much to use my own words in describing that time and those helicopters. In the end, Conklin deserved better.

In the 1970’s, the Grand Gulch Program was a unique experiment when the Bureau of Land Management placed up to six individuals on Cedar Mesa with all the tools imaginable (at that time) to discourage illegal pothunting: horses, mules, jeeps, helicopters and even, in 1974, dirt motorcycles. It was a wild ride and except for the helicopter crash and aftermath, I treasure my years as a Grand Gulch Ranger. I wish Conklin could have said the same.

Great story Jim. I started with BLM in 1978 across the river in the Henry Mountain Field Office in Hanksville. While I never met any of these rangers, they were already legendary as a group of tough, independent (headstrong!) and dedicated people. I transferred over to Moab in 1982, after Gene Day left. I never heard anyone speak a good word about the guy. I did have the privilege of working with Bob Dalla and Bob Turri, and your recollection of them as highly competent and common sense guys looking out for the welfare of their people comes as no surprise.

It’’a too bad they weren’t the managers at that time, they would have listened to these rangers. I also remember the days of unregulated helicopter use and contracts during that era, and am amazed there weren’t more accidents. I had some hairy experiences too in those small helicopters and some hot dog pilots.

Now, it’s just beyond belief to me that Bears Ears had to lock up 2 million acres of land to protect the 200,000 acres of premier archaeological resources on Cedar Mesa. And without the proper staffing in place to handle the mass influx of selfie taking visitors that have now infested the area. It’s a shame public land management couldn’t be left to people on the ground like those rangers, and Dalla and Turri. Now it’s all managed by feckless political appointees, and it’s a broken mess.

I have to admit, I’ve always loved the word, ‘feckless.’ I should use it more, especially nowadays…

Very compelling story. Can’t help but wish things had gone differently for Jim Conklin. You have managed to pay a wonderful tribute to your friend.

Great story Jim! I look forward to getting your emails.

Great story as usual Jim!

I was called into the office of S. Gene Day while working as Supervisory Engineering Technician at the YACC camp in Moab. I recall about 1978. Gene Day wanted two of my work crews (Walt Nunley, John Vicari) to build the back country ranger station at Kane Gulch trailhead. Met him at his office with my direct line boss and camp director Jerry Rogers and refused to assent to do the job without an archeological clearance and EA or EIS.

Day told me I would never get to be an FTE with BLM… told him I follow the laws and look out for the taxpayer since I am one of them.

Miss the year plus spent there go back from time to time to the back country but I don’t miss Moab since it went full on tourist.

Jerry Rodgers is retired and living in Little Rock Arkansas. Walt I lost track of. John was last working at Santa Monica Mountains Natl Recreation Area.

Stephen Verchinski

Albuquerque

Good job and writing Becky and Jim. A really rough time in the ranger program. Great documentation and story telling

Jim–

you’ve been voicing my thoughts and pains with exquisite perfection for half a century, with too little overt support and encouragement from me. I try to imagine this region without you and the gifts you brought us, and I find that image to be missing much, and even darker and more disturbing than the reality that the pimps and promoters and pandering politicians have shat upon us. Thanks for not making that move to Australia. Please live long and keep on keeping on.

Winston Hurst

Hi Winston, Coming from you, that especially means a lot. I’ve been an admirer of you and your work as well over the years, as a voice of common sense and integrity. We need to get together some day and commiserate. That’ seems about all we have left at times. But it is always comforting to connect with kindred spirits. I remember a story of WC Fields, when yet another good friend had passed. He said, “The ranks are thinning.” Before it comes to that, we few need to close ranks and appreciate our shared bonds… Thanks again…Jim

As a former US Navy Aviator, flight instructor, check airman and retired airline captain, I would have agreed in those days that a helicopter was not a safe way to accomplish the objectives of protecting the archaeological treasures of Southeastern Utah. Thank you for for this telling of courageous feats of dedicated rangers who placed themselves in danger until they could not any more.

And as a very amateur archaeologist who has spent many days tramping the ridges, mesas and canyons with him, it’s a tremendous pleasure to see Winston Hurst still active as one of, if not the best archaeologist(s) in the US. Thank you, Jim, for bringing back great memories. – Bill Moore

Hi Jim Stiles

My name if Les Sweeney. The ranger program was put together under my watch. I’m surprised my name was never mentioned. Some things in the article are not factual. I would be more than glad to discuss any part of the story.

Les Sweeney – 208-642-8178