Had it not been for the opportune visit of a certain Pahute Indian with an epicurean twinkle in his small eyes we should have been hopelessly lost.

—Donald Beauregard, 1909

From early times, a tiny community of Paiute Indians made their homes at the bottom of a remote canyon that transects the Arizona/Utah border. Early in 1909, two of them—a father and son—rode eastward on a rocky, fifty-mile-long trail toward Monument Valley in order to patronize a trading post at a place known as Oljato. The father’s name was Mupuutz, which means “Owl” in the Paiute language, although he was better known by the Navajo translation of his name, Nasja (Nd’dshjaa‘), or the name the census takers used for him, Ruben Owl. His son was called Nasja Begay (Nd’dshjaa’ Biye‘), i.e., Owl’s Son. Nasja was in his early seventies, and Nasja Begay was about eighteen.1

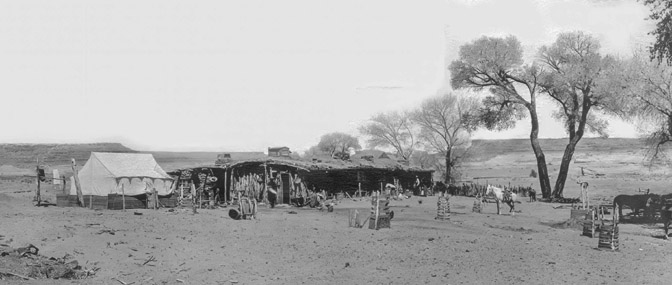

The pioneer trading post at Oljato had been established a few years earlier by John and Louisa Wetherill, my great-grandparents, and Clyde Colville, their trading partner. They were quite fluent with the Navajo language and were learning some Paiute as well. Their store carried basic provisions such as coffee, sugar, baking powder, canned goods, cloth, pots, and implements, which they traded for wool, pelts, weavings, baskets, and silver.

A year or so earlier, an elderly Navajo named One-Eyed Man of the Salt Clan (Ushini Bi-nai-etin) visited the post and told Louisa Wetherill of a beautiful and massive rock bridge that spans a canyon far to the west in the rugged Navajo Mountain country. He died the next fall, quashing John Wetherill’s hope that the old man could lead him to it.

The Wetherills had informed Professor Byron Cummings, of the University of Utah, of the existence of the bridge when he was in Oljato with two of his students in the summer of 1908. Together, they made plans to go there the next summer if the Wetherills could find another guide. Louisa questioned Nasja and Nasja Begay about the bridge, and she was pleased to learn that they both had been there while pasturing their horses. Nasja Begay agreed to lead the journey when summer came again.

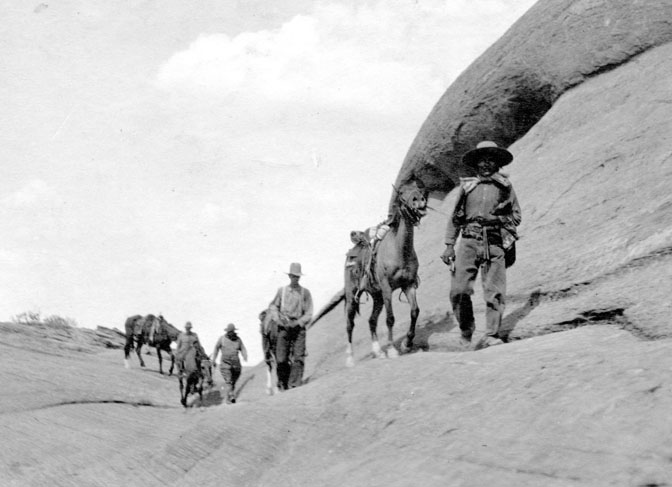

The expedition got underway early in August of 1909. John Wetherill knew the way to Nasja’s home at the Lower Crossing of Paiute Canyon, and they planned to rendezvous with his son there and continue on to the bridge under his guidance.

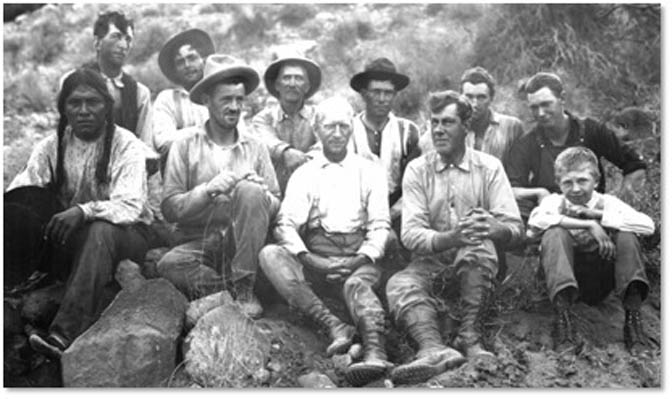

Along with Cummings were his 11-year-old son, Malcolm; students Neil Judd and Stuart Young; young artist Donald Beauregard; and Navajo wrangler Dogeye Begay. Also on the trek was a “rival” group led by William Boone Douglass, who was an examiner of surveys for the U. S. General Land Office. He was accompanied by his Paiute guide, Jim Mike, and assistants Daniel Perkins, John English, Jack Keenan, and Jean Rogerson from southeast Utah.

Because of a delay in getting started, they reached Nasja’s home later than planned. Neil Judd recalled the difficulty this caused:

Beyond the mesa top the trail led down into Piute Canyon, and here, close by green fields of Indian corn, we expected our guide, Nashja-begay. But the old father, toasting cotton-clad shins on the sunny side of his hogan, informed Wetherill his boy had waited until a day or two before, then had gone to the mountains with the family sheep and goats. So we moved on up out of the canyon and through the piñon and cedars that blanket the north slopes of Navajo Mountain. Nashja promised that his son would be recalled immediately and sent on to overtake the party. The old man also refreshed Wetherill’s memory as to prominent landmarks that would be met. 2

Donald Beauregard chronicled the difficulties of the next few days as they worked their way through the tortuous landscape on their own:

[. . .] repeated and hazardous experiences under the glare of a torrid sun, over barren and undulating stretches of desert, through “Royal” gorges with perpendicular walls, over untrailed and unnamed mesas rising 2,000 feet in the air, sliding and slipping over miles of solid sandstone rock, wending patiently through beds of yellow sand, dry and thirsty for water, half blind from the wicked reflection of heat waves, jaded from nights spent in thunderstorms and wet blankets, and finally half starved from a scarcity of provisions. 3

After two days of difficult travel without Nasja Begay to guide them, most of the adventurers were discouraged and ready to give up the quest. Douglass’s guide, Jim Mike, recommended turning back, saying that white man’s horses could go no further. Neal Judd recalled how, that evening, Nasja Begay rode into camp and saved the day:

It was just here, with the party gathered for supper around a canvas spread on the sand, that Nashja-begay arrived. He smiled a friendly greeting and, I like to believe, felt somewhat chagrined that the expedition had advanced so far without him. But the jaded spirit of the party revived so soon as the Piute dismounted and gave attention to his portion of the evening repast. Nashja-begay knew the trail to Rainbow Bridge; he had seen the bridge; Rainbow Bridge was our goal and, despite the doubts entertained by some as to the wisdom and ultimate success of our adventure, hopes rose speedily with the arrival of Nashja-begay. 4

The next morning, August 14, the group headed out under Nasja Begay’s guidance for the last leg of the trip. “The trail was perhaps even more wearisome than that of the day before but the mere presence of Professor Cummings’ Piute guide created a feeling of assurance that smoothed difficulties,” Judd recounted. “Nashja-begay knew the way!” 5

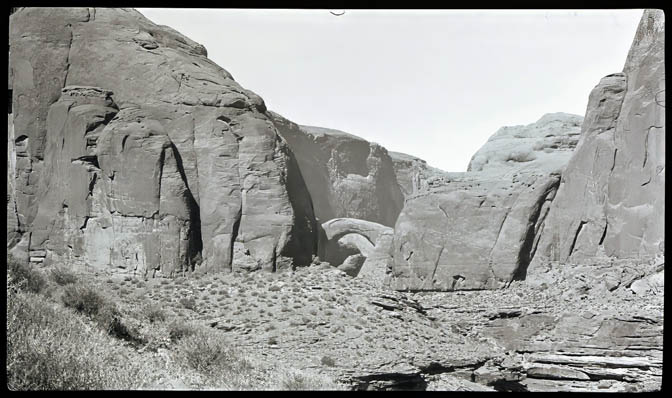

Late that morning, the riders rounded a bend and got their first sight of the bridge. “The first view was dazzling,” one of the expeditioners reported. “Far down the canyon a half mile away, the red-pink bridge stood out against the deep blue and purple of the massive bluffs, rising to a height of five hundred feet above the great roof of the arch. The impressions of that first sight can not be described.” 6 (See my article, “Finding Value in Hardships,” in the April/May 2021 Canyon Country Zephyr for more details on the 1909 expedition).

Near the base of the bridge, Stuart Young assembled the participants and took a commemorative group picture. Missing, however, was Nasja Begay who declined to pose for that or any other photograph.

The enthusiasm of some of the members of the 1909 expedition for the significance of Rainbow Bridge resulted in worldwide publicity of its splendor. In February of 1910, National Geographic Magazine published an article by Byron Cummings entitled “The Great Natural Bridges of Utah.” On May 10, 1910, President Taft created Rainbow Bridge National Monument. Despite its extremely remote location and the difficulties involved with reaching it, demand soon grew for John Wetherill’s guiding and outfitting services. Nasja Begay continued as an integral part of his team.

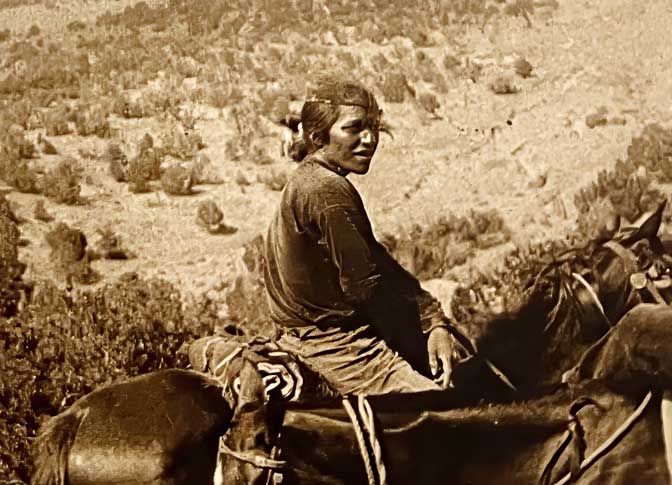

In 1979, my new friend and mentor Stan Jones (aka “Mr. Lake Powell”) guided me over the Rainbow Trail to see the bridge for my first time. He shared with me the story of the 1909 expedition based on his extensive research and speculated that a photo of Nasja Begay might not even exist. Stan was working on a book on the history of Rainbow Bridge, and he was concerned that it would be incomplete without a picture of the young Paiute. However, we had reason for hope of finding a photo of him from later expeditions with which he was involved.

Byron Cummings continued to bring archaeology students to the Navajo Mountain region for summer training outings. “Noscha Begay was a fine, resourceful young man,” he recalled. “He often visited our camps in later years.” Although Cummings dedicated a chapter in his 1952 book, Indians I Have Known, to the guide, he included no image of him. It is doubtful that he had access to one.

The most notable and well-documented Rainbow Bridge post-1909 expeditions that Nasja Begay helped guide were those of the writer, Zane Grey, in May of 1913 (see my article, “The Historic Rainbow Trail,” in the April/May 2018 Canyon Country Zephyr) and former President Theodore Roosevelt in August of 1913 (see my articles “The President Slept Here” in the August/September 2019 Canyon Country Zephyr and “Encounters with the Sublime: Quentin Roosevelt’s Western Adventures” in the November 13, 2022, Canyon Country Zephyr).

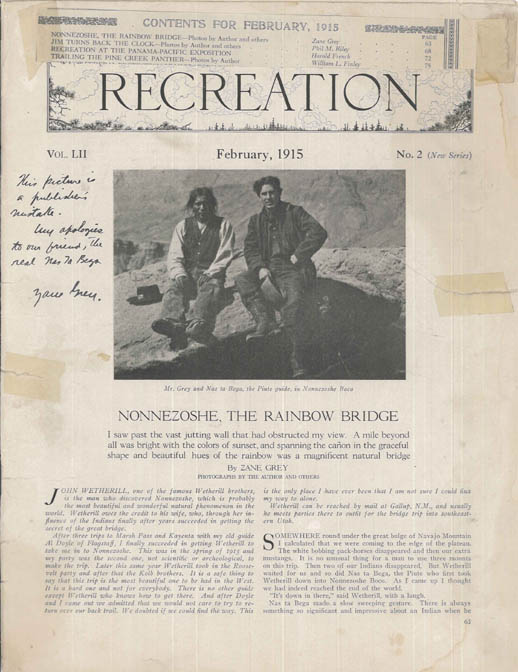

In our search for a photo of Nasja Begay, Stan was elated to find an article by Zane Grey in the February 1915 issue of Recreation magazine entitled “Nonnezoshe, The Rainbow Bridge.” On the first page is a photo captioned “Mr. Grey and Nas ta Bega, the Piute guide, in Nonnezoshe Boco” (i.e., Rainbow Bridge Canyon). Stan spread the word about the photograph, and it was republished in several books and magazine articles as being an authentic photograph of the young man. There was reason to trust Grey’s caption, as he was well acquainted with Nasja Begay. The problem is that the man in the picture beside Grey is not Nasja Begay!

Soon after Stan’s discovery of the Recreation article, I was researching papers in the Otis Marston collection at the Huntington Library in San Marino, California, and came across an original copy of the same article that Zane Grey had sent to John Wetherill. “This picture is a publisher’s mistake,” Grey noted on it. “My apologies to our friend, the real Nas Ta Begay.” 7

Stan was undeterred in his conviction that the photograph was legitimate, and I did not yet have an image of the page with Grey’s inscription to convince him otherwise. We did not discuss the matter any further, and I continued my own quest to uncover more information about Nasja Begay including, hopefully, legitimate photos of him.

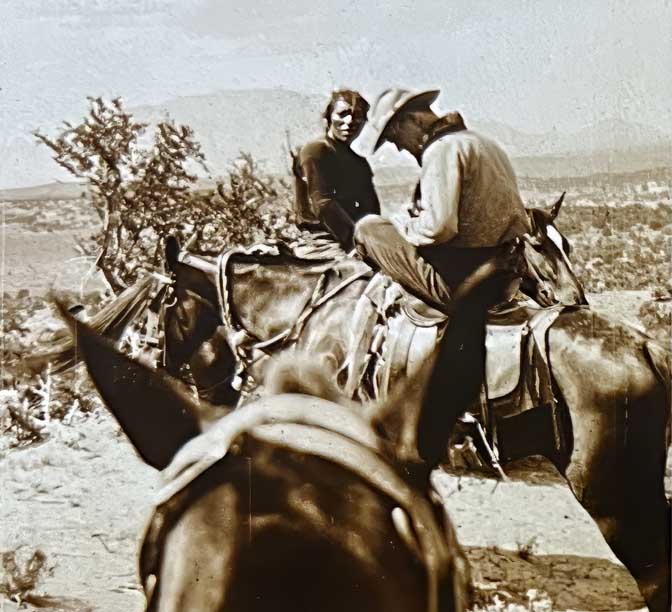

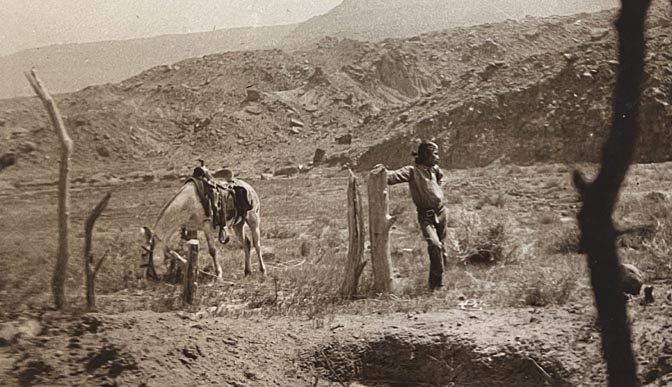

One of our family treasures is a collection of several thousand vintage photographs passed down from the Wetherills. Some twenty or thirty of them are from the August 1913 Theodore Roosevelt expedition to Rainbow Bridge, and I identified that one of them—although unlabeled—most certainly showed Nasja Begay leading the Colonel over a particularly treacherous part of the Rainbow Trail.

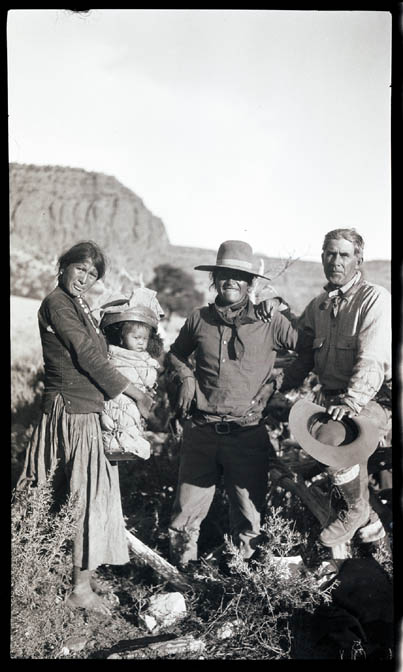

With Nasja Begay’s visage established, I then knew who to look for in other photos. One image in particular was an exceptionally clear scene from one of the Roosevelt campsites, and it shows Nasja Begay to the right of the Colonel. (We also determined, much later, that the man to the left of TR is the guide’s father, Nasja, based on a 1910 photo that I discuss below.)

After finding these photographs, we looked for additional images of Nasja Begay in other collections. In 2018, researchers from the Zane Grey’s West Society were perusing a portion of the massive Zane Grey archive of the L. Tom Perry Special Collections in the Harold B. Lee Library at Brigham Young University and came across several fine photographs that appeared to be of Nasja Begay and his family with Zane Grey. We concluded that the photos were taken during Grey’s 1913 expedition, because Nasja Begay died in 1918 and Grey did not return to the area until 1922.

However, an astute researcher and authority on the history of Zane Grey, Professor Kevin Blake, identified that Grey’s appearance and clothing were identical to those in photos taken on his 1923 expedition to Rainbow Bridge, and he looked older than in photos taken in 1913. We therefore concluded that the BYU images were from 1923, and the young Paiute, who so strongly resembled Nasja Begay, could not have been him. Who, then, was he, and why did Grey pose with him so proudly? Those are questions we have not yet resolved. I suspect, however, that the man was Nasja Begay’s younger brother, Toby Owl.

Accompanying Grey on the 1923 trip were two Hollywood personalities, Jesse Lasky and Lucien Hubbard, who were along to study the geographical and cultural environments of The Rainbow Trail in preparation for producing the movie. Grey attempted to take them to Nasja Begay’s grave, although he failed to find it, and it is reasonable that he also wanted to show them where the guide lived and to introduce them to some of his family.

More recently, I was researching a 1910 expedition to Rainbow Bridge, which also was guided by John Wetherill (see my article, “A 1910 Expedition to Rainbow Natural Bridge,” in the August 13, 2023, Canyon Country Zephyr). The party included New York socialite Martha Blow Wadsworth who, I learned, had recorded hundreds of scenes from the trip. Her images are preserved at the State University of New York in Geneseo. I visited the archive in 2022 to view the collection and was excited to find captioned lantern slides of both Nasja Begay and his father, Nasja. Those led to the identification of two additional, uncaptioned images of Nasja Begay.

From the order of the Wadsworth photos and a knowledge of the lay of the land, the expedition’s route to and from Rainbow Bridge can be determined. On the way to the bridge, they traversed what is known as the Upper Crossing of Paiute Canyon, which is in Arizona. On the return trip, they traveled a different trail that utilized the Lower Crossing, which is in Utah.

On their way to the bridge, the party met up with Nasja Begay.

Although his involvement in the expedition is unclear, he most likely teamed up with Wetherill to help guide the group. On their return trip, they met his father at the Lower Crossing, which is known for its fertile soil and ample spring water that supports orchards and gardens. Nasja kindly presented the weary travelers with a watermelon. Mrs. Wadsworth also photographed Nasja Begay and one of his horses while they were there.

There is little doubt that the Paiute would have continued his friendly and helpful service had he survived, but, tragically, his life was cut short by the great influenza pandemic of 1918. (For more on the pandemic, see my article “Strength in the Face of Adversity: Lessons from the Past” in the June/July 2020 Canyon Country Zephyr.) The Wetherills’ biographer recorded the sad story as told her by Louisa:

During that winter of death some Mormons riding through Monument Valley found five Navajos dead in their blankets. They came back to Kayenta asking the Wetherills to go with them to identify the bodies. No one at that time could leave, and so with the promise that Ben would go later, the Mormons rode back again to the Monuments. There they found a six year old boy, whom they had supposed dead, still alive.

As the reservation was under rigid quarantine, they feared to take the child to Bluff, and left him there with food and blankets until someone should come. The Wetherills heard of the child and sent for him. The Mormon bishop at Bluff, also hearing of him, reproved the man who had left him, and ordered them to return for him.

“Better that all of Bluff had died of the flu than that the boy should be left,” he said.

But when the Wetherills and the Mormons reached Monument Valley, they found the child gone. Tom Holiday, a Navajo, had taken him to his hogan.

The child was the son of Nasja-begay, the Paiute who had led the way to the Rainbow Bridge. Nasja-begay himself had died of the flu at Navajo Mountain. While his family were coming down from the mountain, his wife had also died. The other five kept on, and at last stricken with flu, had wrapped themselves in their blankets and waited for death in the Monuments.

Only the child had survived.

All that winter he was kept by Tom Holiday. Holiday made the six year old child work and herd sheep in order to save his own children. And for six months the boy lived practically as a slave.

When spring came, old Nasja appeared at the hogan seeking his grandchild. Tom Holiday refused to give him up.

“You must give him to me, for he is my son’s son,” old Nasja said insistently.

And finally after paying two horses for the child’s board, Nasja took his grandson away. 8

Byron Cummings returned to Paiute Canyon in 1919 and met Nasja Begay’s son at his grandfather’s hogan. He begged Nasja to let him have the boy. “I told him I would take care of him and send him to school,” Cummings wrote. “The old man looked up at me sadly from his seat on the ground and said, ‘He is all I have.’ I could say no more.” 9

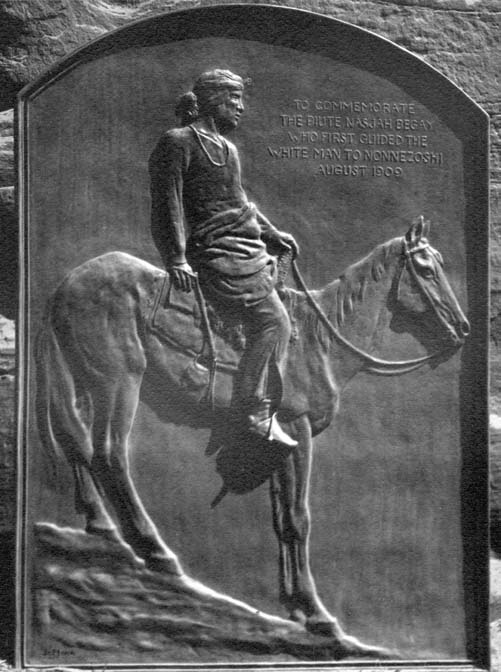

In 1927, after obtaining approval from the National Park Service, John Wetherill led a pack trip to Rainbow Bridge National Monument, dragging a heavy, bronze memorial honoring Nasja Begay on a travois behind a mule. The project was financed by Raymond Armsby of Burlingame, California, and the plaque was designed by the noted artist, Jo Mora. On it is the tribute: “To commemorate the Piute Nasjah Begay who first guided the white man to Nonnezoshi August 1909.” The party ceremoniously installed the plate on a vertical rock surface just south of the bridge. A video of their mission is available online.

Zane Grey must have regretted that he did not photograph Nasja Begay on his 1913 expedition, considering that the Paiute had a powerful spiritual influence on him. They rode together, and Grey was duly intrigued by the guide’s demeanor, competence, adaptation to his wild environment, and back-country skills. “There is always something so significant and impressive about an Indian when he points anywhere. It is as if he says, ‘There, way beyond, over the ranges, is a place I know, and it is far,’” Grey wrote. “The fact was that I looked at the Piute’s dark, inscrutable face before I looked out into the void.” 10

Zane Grey declared Rainbow Bridge to be “probably the most beautiful and wonderful natural phenomenon in the world.” Camping under it the first night, he stayed awake late to enjoy its beauty in the moonlight and noticed his new friend paying homage to the scene in his own way.

The far side of the canon was now a blank black wall. Over its towering rim showed a pale glow. It brightened. The shades in the canon lightened, then a white disk of moon peeped over the dark line. The bridge turned to silver.

It was then that I became aware of the presence of Nas ta Bega. Dark, silent, statuesque, with inscrutable face uplifted, with all that was spiritual of the Indian suggested by a somber and tranquil knowledge of his place there, he represented to me that which a solitary figure of human life represents in a great painting. Nonnezoshe needed life, wild life, life of its millions of years—and here stood the dark and silent Indian. 11

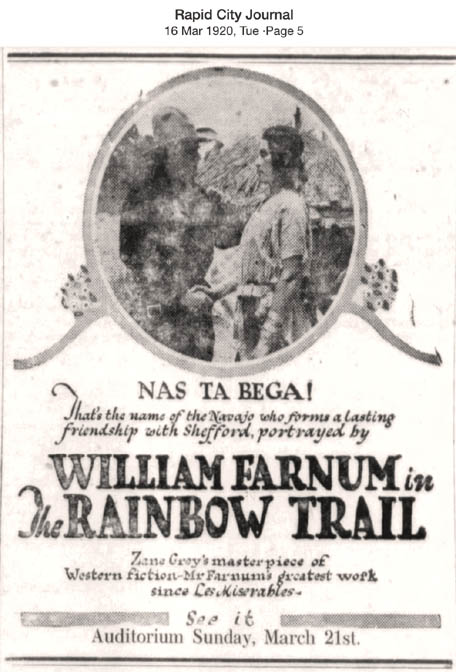

Besides his non-fictional account of the 1913 expedition in his Recreation magazine article, Grey used the people and places he encountered as source material for a romance novel, The Rainbow Trail. One of his primary characters is a Navajo man, Nas Ta Bega. The character had nothing in common with the real Nasja Begay except for the name. A subsequent movie adaptation further publicized the Paiute guide’s name.

Grey returned to Rainbow Bridge in 1922, 1923, and 1929. On his last visit, he was downhearted that the experience failed to arouse his old delight in the place. Deep in the night, unable to sleep, his mind revived the memory of the way it used to be and his old friend and guide, the late Nasja Begay. “Nas ta Bega came to me then. He was there in the shadow—the soul of the Indian. I did not question and doubt. I grasped that truth to my living soul. He gazed up at Nonnezoshe with me, but while he understood, I could not pierce beyond the physical confines of that lovely canyon.” 12

The contrast between the lifestyles of Nasja Begay and his clients was extreme. He lived simply with few possessions and no modern conveniences, yet the photographs of him suggest that he was at peace with his lot in life and radiated enthusiasm, authenticity, and competence.

When my friend and mentor, Stan Jones, introduced me to the Navajo Mountain region in 1979, we spent some time at the Navajo Mountain Trading Post where we visited with the pioneer trader, Madelene Cameron. We noticed an elderly Native American man at the post, and Madelene told us he was Toby Owl, Nasja Begay’s brother. I had the privilege of meeting him. More recently, I was pleased to become acquainted with another descendant of Nasja, Lavern Owl, who is keeping her family’s story alive. I was honored to meet both of them and gratified to think of their family’s legacy and their esteemed relatives’ friendship with my own ancestors.

*****

ABOUT HARVEY LEAKE:

More than thirty years ago, Harvey Leake began researching the history of his pioneering ancestors, the Wetherills of the Four Corners region. His investigations have taken him to libraries, archives, and the homes of family elders whose recollections, photographs, and memorabilia have brought the story to life. His field research has led him to remote trading post sites in the Navajo country and some of the routes used by his great-grandfather, John Wetherill, to access the intricate canyon country of the Colorado Plateau. Harvey was born and raised in Prescott, Arizona. He is a semi-retired electrical engineer.

To peruse all of Harvey’s brilliant Zephyr contributions, click here.

NOTES & SOURCES

1 The 1937 Indian Census Roll for the Western Navajo jurisdiction lists Ruben Owl as being 100 years old. An explorer in 1916 named George Fraser hired a young Paiute guide who called himself “John” and who he estimated to be twenty-two years old (George C. Fraser, Journeys in the Canyon Lands of Utah and Arizona, 1914–1916,Tucson: University of Arizona Press, 2005). A historian concluded that John was Nasja Begay (Stephen Jett, “The Journals of George C. Fraser ’93: Early Twentieth-Century Travels in the South and Southwest, ”Princeton University Library Chronicle35 [Spring 1974]: 290–308). Given Nasja Begay’s maturity and independence one earlier expeditions, I suspect that Fraser underestimated his age in 1916.

2 Neil M. Judd, “Rainbow Trail to Nonnezoshe,”National Parks and Conservation Magazine, November 1973: 4–8.

3 Donald Beauregard, “‘Nonnezhozhi,’ the Father of All Natural Bridges,”Deseret Evening News, October 2, 1909: part 2, page 1.

4 Neil Merton Judd, “The Discovery of Rainbow Bridge, ”National Parks Bulletin54 (November 1927): 13.

5 Ibid.

6 “Dean Cummings Successful, ”The Chronicle(University of Utah), 18:1 (September 28, 1909): 1–2.

7 Further research determined that the photo was taken on Johnson Point above Lees Ferry, Arizona, on Zane Grey’s first visit there in 1907 on his way to the North Rim of the Grand Canyon. We have not determined the name of the Paiute man.

8 Frances Gillmor, A Biography of John and Louisa Wetherill, Master of Arts dissertation, University of Arizona,1931: 157–9.

9 Byron Cummings, Indians I Have Known, Tucson: Arizona Silhouettes, 1952: 45.

10 Zane Grey, “Nonnezoshe, The Rainbow Bridge,”Recreation,February1915.

11 Zane Grey, Tales of Lonely Trails, New York: Harper & Brothers, 1922: 16.

12 Zane Grey, Fading Indian Trails, unpublished manuscript, Ohio Historical Society, Columbus

TO COMMENT ON THIS STORY, PLEASE SCROLL TO THE BOTTOM OF THIS PAGE.

And I encourage you to “like” & “share” individual posts.

Why they can’t just leave the site alone is beyond me,

but that’s what Facebook likes to do.

ALSO NOTE: I post old photographs and stories from our 25 year old archives every day. Pictures from Herb Ringer, Edna Fridley, Charles Kreischer.. even a few old photos from my Dad. So if you want to stay caught up on our historic photo collections,

be sure to “follow” us on Facebook…Thanks…Jim

https://www.facebook.com/FansoftheCanyonCountryZephyr/

https://www.facebook.com/FansoftheCanyonCountryZephyr/

$55 Each or Two for $100 (Free Shipping.)

https://www.facebook.com/profile.php?id=100086441524150

http://www.canyoncountryzephyr.com/advertise/indexnewz.htm

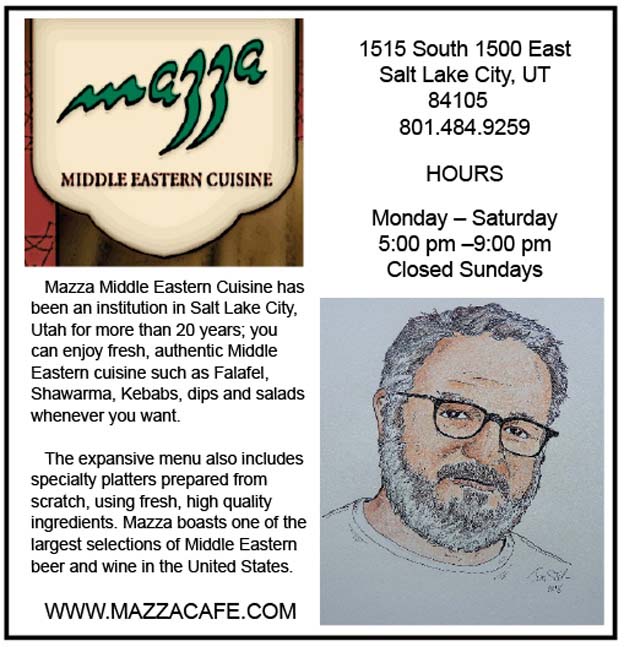

And check out this post about Mazza & our friend Ali Sabbah,

and the greatest of culinary honors:

https://www.saltlakemagazine.com/mazza-salt-lake-city/

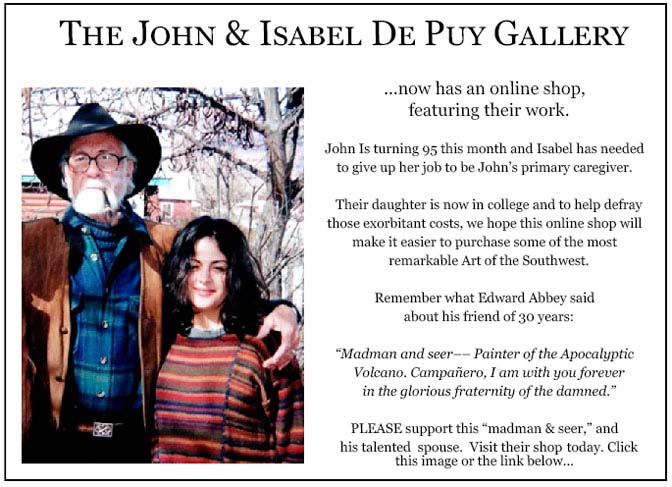

More than six years ago, The Zephyr, me & four other individuals were sued for defamation by the former Moab City Manager. Faced with mounting legal bills, my dear friends John and Isabel De Puy donated one of John’s paintings to be auctioned.

ALL the proceeds went to our defense.

Thanks to them, our bills were almost completely covered.

Now I’d like to return the favor. Check out the link below and their online shop… JS

https://www.depuygallery.com/

https://www.canyoncountryzephyr.com/

TO COMMENT ON THIS STORY OR TO EXPRESS AN OPINION, PLEASE SCROLL TO THE BOTTOM OF THIS PAGE. THANKS…Jim Stiles

.

Another fascinating story re the Rainbow Bridge and the Indian guides. The young Begay certainly made a favorable impression on those he guided. Glad he was commemorated with that plaque!

I’ve been a part of this remote territory for a long time now.

The first time I hikes into Rainbow Bridge was in 1966. I remember it so clearly.

Too old to go into the back country these days. So, it sure is good to read about it and learn a little more.

Thanks for posting this wonderful article.

Another winner! Thanks Jim. My first trip to Rainbow Bridge was easy. We traveled by boat from Halls Crossing. My grandmother, at age 53, accompanied what I believe was the first group from Blanding that rode to the bridge on horse back in 1940. Whilst they were on the trail, her 23-year-old son eloped with his girlfriend and got married.

Yet another reason to wish for a chance to see what they saw, and to be grateful that the Zephyr is still on the case, bringing us the opportunity.

During a visit to the bridge in 1971 a carving in the stone downstream from the bridge was pointed out the name: Grey and a date. The date escapes me but 15 sticks n my mind. Moreover I don’t remember a Z but there may have been one as proof of the carver.

Yet another great account by Harvey. Thanks, Jim, for posting it. I have been interested in the Paiute residents of the Navajo Mountain region for quite some time, and have had the pleasure of visiting their homeland with Lavern Owl in search of Paiute place names. Harvey’s research and article contain much new information, even to me!

Simply remarkable. The canyons and flats surrounding Navajo Mountain have changed little since then, a the original trail is still used by many who seek Rainbow Bridge. It takes a committed soul to traverse those trails, but the serenity, mystery and beauty are still there.

Great essay and research. Really enjoyed the Wadsworth expedition photos and the ‘rest of the story’ on the Owl family.

When we moved to Fry Canyon in the early 60s my dad took us to see the Rainbow Bridge and we signed our name on the guest list. An amazing place. We ad a fun year around that area hiking and picking up pottery pieces and exploring the land. We went to school in fry canyon.

Thanks for the excellent write up. My parents, Merritt and Winona Holloway, contracted with Barry Goldwater to operate Rainbow Lodge for the 1952 season. I was eight years old, and made eight trips to the bridge that year, as my dad’s mule wrangler and camp helper. It was always a thrill to round the last curve in Bridge Canyon and see the bridge, much like the photo in this article. My mother wrote about our family’s experience in her book, “Riders to the Rainbow, Traders to The People.” Email me and I’ll send you a copy.

Tom, thank you for your kind comments. I knew your dear parents and have a copy of their book.

Thank you Jim and Harvey, as always great writing!